Battle of Marathon

| Battle of Marathon | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Greco-Persian Wars | |||||||||

The plain of Marathon today |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Athens, Plataea |

Achaemenid Empire | ||||||||

| Commanders | |||||||||

| Miltiades the Younger, Callimachus †, Arimnestus |

Datis †?, Artaphernes |

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 7,000 to 10,000 Athenians, 1,000 Plataeans |

20,000 to 60,000 a | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 192 Athenians, 11 Plataeans (Herodotus) |

6,400, 7 ships captured (Herodotus) |

||||||||

| a These are modern consensus estimates. Ancient sources give numbers ranging from 200,000 to 600,000; these are generally thought to be over-estimates. | |||||||||

|

|||||

The Battle of Marathon (Greek: Μάχη τοῡ Μαραθῶνος, Machē tou Marathōnos) during the Greco-Persian Wars took place in 490 BC and was the culmination of the first attempt by the Achaemenid Empire of Persia, under King Darius I, to subjugate Greece. The principal objective of this phase of the Greco-Persian wars was the punishment of Athens and Eretria for support given to the Ionian cities during the Ionian Revolt (499-494 BC), but with the general aim of bringing Greece into the Persian Empire[1]. Much of what is known of the campaign and specifically this battle comes from the Greek historian Herodotus in his Histories.

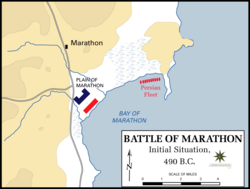

In 492 BC, a Persian army under Mardonius was sent to re-pacify Thrace (which had been under Persian rule for around 25 years), and subjugate Macedon. This secured the approaches to Greece for Persia. After diplomatically obtaining the submission of most Greek city states in 491 BC, Persia had left Athens and Sparta isolated as the remaining beligerent parties in Greece. Finally, in 490 BC, the Persian generals Datis and Artaphernes (son of Artaphernes) were sent in a maritime operation to subjugate the Cycladic islands in the central Aegean and punish Eretria and Athens for their assistance in the Ionian Revolt. Eretria was besieged and fell; the Persian army then landed in Attica, near the town of Marathon.

To meet them the Athenians, joined by a small force from Plataea, marched to Marathon, and succeeded in blocking the two exits from the plain of Marathon. Stalemate ensued for five days, until part of the Persian force, including the cavalry, was sent by sea to attack Athens directly[2]. With the cavalry threat to the hoplite phalanx removed, and needing to act quickly to prevent the conquest of Athens, the Greeks attacked the remaining Persian army at dawn on the sixth day. Despite the numerical advantage of the Persians, the hoplites proved devastatingly effective, routing the Persians wings and achieving a double envelopment of the centre[3].

The Battle of Marathon was a watershed in the Greco-Persian wars, showing the Greeks that the Persians could be beaten. The seed for the eventual Greek triumph in these wars was sown at Marathon. Since the following two hundred years saw the rise of the Classical Greek civilization, which has been enduringly influential in western society[4][5], the Battle of Marathon is sometimes seen as pivotal moment in European history. For instance, John Stuart Mill famously suggested that "the Battle of Marathon, even as an event in British history, is more important than the Battle of Hastings"[6]. The Battle of Marathon is perhaps now more famous as the inspiration for the Marathon race. Although historically inaccurate, the legend of a Greek messenger running to Athens with news of the victory became the inspiration for this athletics event, introduced at the 1896 Athens Olympics, and originally run between Marathon and Athens.[7]

Contents |

Background

In 511 BC, with the aid of Cleomenes I, King of Sparta, the Athenian people expelled Hippias, the tyrant ruler of Athens.[8] With Hippias' father Peisistratus, the family had ruled for 36[8] out of the previous 50 years and intended to continue Hippias' rule. Hippias fled to Sardis to the court of the Persian satrap, Artaphernes and promised control of Athens to the Persians if they were to restore him.[9]

In the meantime, Cleomenes helped install a pro-Spartan tyranny under Isagoras in Athens; in opposition to Cleisthenes, leader of the traditionally powerful Alcmaeonidae family, who considered themselves the natural heirs to the rule of Athens. In response, Cleisthenes proposed to the people that he would establish a democracy in Athens, much to the horror of the rest of the aristocracy. Cleisthenes and his family were thereby exiled from Athens, as well as other dissenting elements. However, seizing the moment, the Athenians people revolted, expelling Cleomenes and Isogoras.[10] Cleisthenes was thus restored to Athens (507 BC), and at breakneck speed began to establish democratic government. The establishment of democracy revolutionised Athens, which henceforth became one of the leading cities in Greece.[10] The new found freedom and self-governance of the Athenians meant that they were thereafter exceptionally hostile to the return of the tyranny of Hippias, or any form of outside subjugation; by Sparta, Persia or anyone else.[10]

Cleomenes, unsurprisingly, was not pleased with events, and marched on Athens with the Spartan army. Cleomenes's attempts to restore Isagoras to Athens ended in a debacle, but the Athenians had by this point already sent an embassy to Sardis, to request Persian aid. Artaphernes requested that the Athenians give him a 'earth and water', a traditional token of submission and then instructed the Athenians to take Hippias back as tyrant [11]. Needless to say, the Athenians baulked at this, and, in the end, Persian aid was not needed. However, their experience of the Persians led the Athenians, a decade later (498 BC), to give assistance to the Ionian cities. These had overthrown their Persian-appointed tyrants, and had declared themselves democracies; this was the so-called Ionian Revolt (499 BC–494 BC).[12] The city of Eretria also sent assistance to the Ionians. The Greek task force surprised and outmaneuvered Artaphernes, marching on, and then burning, the lower city of Sardis[13]. However, this was as much as the Greeks achieved, and they were then pursued back to the coast by Persian horsemen, losing many men in the process. Despite their rather inconsequential actions, the Eretrians and in particular the Athenians had earned Darius's lasting enmity, and he vowed to punish the cities [14].

In 492 BC, once the Ionian Revolt had finally been crushed, Darius dispatched an army under the command of his son-in-law, Mardonius, to Greece. Mardonius re-conquered Thrace and compelled Alexander I of Macedon to make Macedon a client kingdom to Persia. However, while en route south to the Greek city-states, the Persian fleet was wrecked in a storm off Cape Athos, losing 300 ships and 20,000 men.[15] Mardonius then retreated to Asia, amid attacks by Thracian tribes which inflicted losses on the retreating army.[16]. Nevertheless, the land approaches to the Greece were secured, and a clear message had been sent to the states of Greece, showing what awaited them if they failed to submit.[17]

In 491 BC, Darius sent ambassadors around Greece, asking for earth and water, indicating the submission of the city-states. The vast majority of cities did as asked. In Athens, however, the ambassadors were put on trial and then executed; in Sparta, they were simply thrown down a well [17]. This firmly and finally drew the battle-lines for the coming conflict; Sparta and Athens, despite their recent enmity, would together fight the Persians.

It was thus, in 490 BC, following up the successes of the previous campaign, that Darius decided to send a maritime expedition led by Artaphernes, (son of the satrap to whom Hippias had fled) and Datis, a Median admiral. Mardonius had been injured in the prior campaign and had fallen out of favor. The expedition was intended to bring the Cycladic islands of the Aegean into the Persian empire, to punish Naxos (which had resisted a Persian assault in 500 BC) and then to head to Greece to force Eretria and Athens to submit to Darius or be destroyed[18].

By late July, the Persians had arrived off Euboea, where they proceeded to besiege, capture and burn Eretria. They then headed south down the coast of Attica, landing at the bay of Marathon, roughly 25 miles (40 km) from Athens. Under the guidance of Miltiades, the general with the greatest experience of fighting the Persians, the Athenian army marched to block the two exits from the plain of Marathon. At the same time, Athens' greatest runner, Pheidippides (or Philippides) had been sent to Sparta to request that the Spartan army march to Athens' aid. Pheidippides arrived during the festival of Carneia, a sacrosanct period of peace, and was informed that the Spartan army could not march to war until the full moon rose; Athens could not expect reinforcement for at least ten days.[19] The Athenians would have to hold out at Marathon for the time being, although they were reinforced by a contingent of hoplites from Plataea; a gesture which did much to steady the nerves of the Athenians.[19]

Date of the battle

Herodotus mentions for several events a date in the lunisolar calendar, of which each Greek city-state used a variant. Astronomical computation allows us to derive an absolute date in the proleptic Julian calendar which is much used by historians as the chronological frame. August Böckh in 1855 concluded that the battle took place on September 12, 490 BC in the Julian calendar, and this is the conventionally accepted date. However, this depends on when the Spartans held their festival and it is possible that the Spartan calendar was one month ahead of that of Athens. In that case the battle took place on August 12, 490 BC.[20]

The opposing forces

The Athenians

Modern historians favor that the whole Greek army numbered c. 10,000 hoplites,[21] with the Athenian hoplites numbered at c. 9,000 and the little Platean contingent at c. 1,000 men.[22] Some have given around 7,000–8,000 and others 11,000 (10,000 Athenians and 1,000 Plataeans).[23] Pausanias asserts it did not surpass 9,000,[24] while Justinus[25] and Cornelius Nepos[26] both give 10,000 as the number of the Greeks. Herodotus tells us that at the battle of Plataea eleven years later the Athenians sent 8,000 hoplites while others were at the same time engaged as epibates in the fleet that later fought at the battle of Mycale. Pausanias noticed in the trophy of the battle the names of former slaves who were freed in exchange for military services.[27] Also, it is possible that metics, non-Athenian Greeks residing in Athens, were drafted since they had military obligations to Athens in times of great emergency (for example in 460 BC). However, for Marathon, this is not mentioned by any surviving source, and their number in Athens was not as significant in 490 BC as it became later in the century when Athens became head of the Delian League.

Athens, such was the population at the time, could have fielded four times the force which is estimated to have been sent, if the Athenians had chosen to send light troops consisting of the lower classes. Ten years later at the Battle of Salamis it had a 180 trireme fleet[28] that was manned by 32,000 rowers. There has been some speculation as to why this did not happen.[23] The most simple explanation is that the lower classes were not trained to fight and had no experience nor equipment; whereas before Salamis, the whole population of Athens had been evacuated, with all the men training for months to row the newly built triremes.[29] Furthermore, Athens was waiting for a Spartan army to arrive, and did not initially intend to attack the Persians until then.[19]

The Persians

According to Herodotus, the fleet sent by Darius consisted of 600 triremes,[30] whereas according to Cornelius Nepos, there were only 500.[31] The historical sources do not reveal how many transport ships accompanied them, if any. According to Herodotus, 3,000 transport ships accompanied 1,207 ships during Xerxes' invasion in 480 BC.[32] Stecchini estimates the whole fleet comprised 600 ships altogether: 300 triremes and 300 transports;[33] while Peter Green[34] suggests there were 200 triremes and 400 transports. Ten years earlier, 200 triremes failed to subdue Naxos, so a 200 or 300 trireme fleet would perhaps have been inadequate for all three objectives.[35]

Herodotus does not estimate the size of either army. Of the Persian army, he says they were a large infantry that was well packed.[36] Among ancient sources, the poet Simonides, another near-contemporary, says the campaign force numbered 200,000; while a later writer, the Roman Cornelius Nepos estimates 200,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry, of which only 100,000 fought in the battle, while the rest were loaded into the fleet that was rounding Cape Sounion,[31] Plutarch[37] and Pausanias[38] both independently give 300,000, as does the Suda dictionary;[39] Plato[40] and Lysias assert 500,000;[41] and Justinus 600,000.[25]

Modern historians have also made various estimates. As Kampouris has noted,[23] if the 600 ships were warships and not transport ships, with 30 epibates (the ships' marines, this number was typical for Persian ships after the Battle of Lade) the number 18,000 is attained for the troops. However, the fleet must have had at least some proportion of transport ships, since the cavalry was carried by ship; whilst Herodotus claims the cavalry was carried in the triremes, this is improbable. Estimates for the cavalry are usually in the 1,000–3,000 range,[42] though as noted earlier Cornelius Nepos gives 10,000.

Other modern historians have proposed numbers for the infantry. Bengtson[43] estimates there were no more than 20,000 Persians; Paul K. Davis estimates there were 20,000 Persians;[44] Martijn Moerbeek estimates there were 25,000 Persians;[45] Bussolt and Glotz talk of 50,000 battle troops;[46][47] Stecchini estimates there to have been 60,000 Persian soldiers in Marathon;[33] Kleanthis Sandayiosis talks of 60,000 to 100,000 Persian soldiers[48]; while Peter Green talks of 80,000 including the rowers;[34] and Christian Meier talks of 90,000 battle troops.[49] Scholars estimating relatively small numbers for Persian troops argue that the army could not be very big in order to fit in the ships. The counterargument of scholars who claim large numbers is that if the Persian army was small, then the Eretrians combined with the Athenians and Plateans could match it, and possibly have sought battle outside Eretria. Naxos alone could field "8,000 shields" in 500 BC and with this force successfully defended against the 200-ship Persian invasion 10 years earlier.[50]

Composition and formation of Persian forces

The bulk of Persian infantry were probably Takabara lightly armed archers; several lines of evidence support this. First of all, Herodotus does not mention a shield wall, which was typical of the heavier Sparabara formation, at Marathon; whereas he specifically mentions it regarding the Battle of Plataea and the Battle of Mycale. Also, in the depiction of the Battle of Marathon in the Stoa, which was dedicated a few years later in 460 BC when most veterans of the war were still alive (and which is described by Pausanias), only Takabara infantry are depicted.[51] Finally, it seems more likely that the Persians would have sent the more multipurpose Takabara soldiers for a maritime operation than the specialized Sparabara heavy (by Persian standards) infantry.[23] The Takabara troops carried a small woven wicker shield, probably incapable of withstanding heavy blows from the long spears of the hoplites. The usual tactic of the Persian army was for the archers to shoot volleys of arrows to weaken and disorganise their enemy, after which their strong cavalry moved in to rout the opposition. On the other hand, the Ασπις (aspis), the heavy shield of the hoplites, was capable of protecting the man who was carrying it (or more usually the man on his left) from both the arrows and the spears of its enemies. The Persians were also at a disadvantage due to the size of their weapons. Hoplites carried much longer spears than their Persian enemies, extending their reach as well as protecting them.[52] Persian armies would usually have elite Iranian troops in the center and less reliable soldiers from subject peoples on the flanks of the formation. It is confirmed by Herodotus that this is how the Persian army was arrayed in the battlefield.[53]

The front of the Greek army probably numbered c. 1600 men (c.10,000 men in c.8 ranks). If the Persians had the same frontal spacing as the Greeks and were 10 ranks strong then the Persian army opposing the Greeks numbered 16,000 men.[23] However, if the front had a gap of 1.4 meters between soldiers compared to 1 meters for every Greek and had a density of 40 to 50 ranks as seems to be the maximum possible for the plain, then the Persian army would have numbered 44,000 to 55,000.[42] If the Persian front numbered 2,000 men and they fought in 30 ranks (as Xenophon in Cyropaedia claims) then they numbered 60,000. Kampouris suggests it numbered 60,000, since that was the standard size of a major Persian formation.[23]

Strategic & tactical considerations

Strategically and tactically the Athenians were at a significant disadvantage. This was principally a matter of numbers. In order to face the Persians in battle, the Athenians had had to summon all available hoplites; and even then they were still outnumbered at least 2 to 1. Furthermore, raising such a large army had denuded Athens of defenders, and thus any secondary attack in the Athenian rear would cut the army off from the city; and any direct attack on the city could not be defended against. Still further, defeat at Marathon would mean the complete defeat of Athens, since no other Athenian army existed. Everything was staked on winning at Marathon, which meant that risks could not be taken lightly. The Athenian strategy was therefore to keep the Persian army pinned down at Marathon, blocking both exits from the plain, and thus preventing themselves from being outmanoeuvred[19]. However, this defensive strategy could not deliver the decisive victory needed (unless the Persians risked a frontal attack on the Athenian positions). Only the arrival of the Spartan army might allow the Greeks to move onto the offensive. Time therefore worked in favour of the Athenians[19]. Tactically, the hoplites were very vulnerable to attacks by cavalry, and the Athenians had no cavalry to defend their flanks. Since the Persians had substantial numbers of cavalry, this made any offensive manouever by the Athenians even more of a risk, and thus reinforced the defensive strategy of the Athenians.[2]

Conversely, the Persians enjoyed several corresponding strategic advantages. Firstly, their greater numbers allowed greater flexibility and the potential to divide their forces.[2] Secondly, the possession of a strong fleet allowed them to try and outmanoeuver the Athenians by sea.[2] Thirdly, the Persians did not necessarily need a decisive victory in this encounter. However, as noted above, as time went on, their strategic situation would worsen. Tactically, the Persians, only lightly armoured, could not risk a frontal assault on the fortified Athenian lines.[2] They therefore required the Athenians to leave their lines if they were to fight at Marathon. There was less at stake for the Persians at Marathon, and if no Athenian attack occurred, they would be able to withdraw and attack elsewhere. The end result of these strategic and tactical situations was one of stalemate, with neither side able to attack.[2]

Prelude

For five days the armies therefore confronted each other across the plain of Marathon, in stalemate. The Athenian army slowly narrowed the distance between the two camps, using pikes cut from trees to cover their flanks against cavalry movements.[54] Since every day brought the arrival of the Spartans closer, this time worked in favor of the Athenians.[19] It was probably therefore the Persians that decided to break the stalemate. On the fifth day, either September 11, or possibly August 11, reckoned in the proleptic Julian calendar, Artaphernes decided to move and attack Athens with one portion of the army, whilst the other kept the Athenians pinned at Marathon.[2] The Athenians came to know of this from two Ionian defectors; and specifically that the Persian cavalry had left Marathon that evening. This critical absence has been a matter of debate. Historians have supposed that this was either because the cavalry had been boarded onto ships and sent to attack Athens by sea[19]; or that it was inside the camp since it could not stay in the field during the night[42]; or that it was moving elsewhere on land to reach Athens.[23] It should be noted that Herodotus does not specifically mention where the Cavalry had gone.

With the cavalry gone, the Athenians were in a much better tactical position, though still heavily outnumbered. However, if the cavalry had indeed been sent by boat to attack Athens, then they were in danger of being outmanoeuvered and returning to a conquered city.[2] According to Herodotus, by this point the generals had decided to give up their rotating leadership as prytanevon generals in favor of Miltiades. Miltiades, understanding the situation, persuaded the other generals that this was the moment to attack, despite the risks. The decision was made to attack at dawn the next day.[2]

The battle

The distance between the two armies at this point had narrowed to "a distance not less than 8 stadia" or about 1,500 meters. The hoplites armed themselves and formed up for the attack. Miltiades ordered the two tribes that were forming the center of the Greek formation, the Leontis tribe led by Themistocles and the Antiochis tribe that was led by Aristides,[55] to be arranged in the depth of 4 ranks while the rest of the tribes at their flanks were in ranks of 8. The simple signal was then given to advance by Miltiades: "At them".[2] According to legend, they ran the whole distance to the Persian lines, shouting their ululating war cry, "Ελελευ! Ελελευ!" ("Eleleu! Eleleu!"). All this was much to the surprise of the Persians who "in their minds they charged the Athenians with madness which must be fatal, seeing that they were few and yet were pressing forwards at a run, having neither cavalry nor archers"[56]. It is a matter of debate whether the Greek army actually ran the whole distance, or marched until they reached the limit of the archers' effectiveness, the "beaten zone", or roughly 200 meters, and then ran towards the ranks of their enemy. Proponents of the latter opinion note that it is very hard to run that large a distance carrying the heavy weight of the hoplitic armor, estimated at 32 kilograms (70.5 pounds)[57].

As the Greeks advanced, their strong wings drew ahead of the center, which appears to have retreated (or at least advanced more slowly). This retreat must have been significant since Herodotus mentions that the center retreated towards Mesogeia, not several steps[53]. The thinning of the centre of the Athenian line (rather than the even redistribution of troops across the front) also suggests a deliberate ploy to draw the Persian centre forward. Passing through the hail of arrows launched by the Persian army, protected for the most part by their armour, the Greek line finally collided with the enemy army. Holland [58] suggests the likely consequences:

- "The Athenians had honed their style of fighting in combat with other phalanxes, wooden shields smashing against wooden shields, iron spear tips clattering against breastplates of bronze...in those first terrible seconds of collision, there was nothing but a pulverizing crash of metal into flesh and bone; then the rolling of the Athenian tide over men wearing, at most, quilted jerkins for protection..."

The Athenian wings quickly routed the inferior Persian levies on the flanks, before turning inwards to surround the Persian centre, which had been more successful against the thin Greek centre. The result was a double envelopment, and the battle ended when the whole Persian army, crowded into confusion, broke back in panic towards their ships and were pursued by the Greeks[53]. Some, unaware of the local terrain, ran towards the swamps where unknown numbers drowned. Most Athenian casualties were sustained during the last phase of the battle, as they desperately tried to stop the Persians launching their ships.[59].

Aftermath

Herodotus records that 6,400 Persian bodies were counted on the battlefield,[60] and it is unknown how many perished in the swamps. Seven Persian ships are mentioned as having been captured, though none appear to have been sunken.[61] The Athenians lost 192 men[60] and the Plataeans 11[62], most during the final chase when their heavy armor proved a disadvantage. Among the dead was the war archon Callimachus and the general Stesilaos. One story documents that Kynaigeirus, brother of the playwright Aeschylus who was also among the fighters, charged into the sea, grabbed one Persian trireme, and started pulling it towards shore. A member of the crew saw him, cut off his hand, and Kynaigeirus died.[59] According to Ctesias, Datis was slain at Marathon[63]. Herodotus, however, has him alive after the battle returning a statue of Apollo to Delos that had earlier been removed by his army[64], though he does not mention him after the remnant of the army returned to Asia.

As soon as the Persian survivors had put to sea, the two center tribes stayed to guard the battlefield and the rest of the Athenians marched to Athens. A shield had been raised over the mountain near the battle plain, which was either the signal of a successful Alcmaeonid revolution or (according to Herodotus) a signal that the Persian fleet was moving towards Phalerus.[61] They arrived in time to prevent Artaphernes from securing a landing. Seeing his opportunity lost, Artaphernes turned about and returned to Asia[65].

On the next day, the Spartan army arrived, having covered the 220 kilometers (136.7 miles) in only three days. The Spartans toured the battlefield at Marathon, and agreed that the Athenians had won a great victory.[66]

The dead of Marathon were awarded by the Athenians the special honor of being the only ones who were buried where they died instead of the main cemetery of Athens in Kerameikos.[67] On the tomb of the Athenians this epigram composed by Simonides was written:

- Ελλήνων προμαχούντες Αθηναίοι Μαραθώνι

- χρυσοφόρων Μήδων εστόρεσαν δύναμιν

- The Athenians, as defenders of the Hellenes, in Marathon

- destroyed the might of the golden-dressed Medes[68]

The battle was also a defining moment for the young Athenian democracy, showing what might be achieved through unity and self-belief; indeed, the battle effectively marks the start of a 'golden age' for Athens [10]. It seems that the playwright Aeschylus considered his participation at Marathon to be his greatest achievement in life (rather than his plays) since on his gravestone there was the following epigram:

- Αἰσχύλον Εὐφορίωνος Ἀθηναῖον τόδε κεύθει

- μνῆμα καταφθίμενον πυροφόροιο Γέλας·

- ἀλκὴν δ’ εὐδόκιμον Μαραθώνιον ἄλσος ἂν εἴποι

- καὶ βαρυχαιτήεις Μῆδος ἐπιστάμενος

- This tomb the dust of Aeschylus doth hide,

- Euphorion's son and fruitful Gela's pride

- How tried his valor, Marathon may tell

- And long-haired Medes, who knew it all too well.[69]

The Greek defeat of the Persians, who had not been defeated on land for many decades (except by Samagaetes and Scythes, both nomadic tribes), caused problems for the Persians. The Persians were shown to be vulnerable. Darius still fully intended to punish the Athenians, and now the Spartans; however, oppressed by Darius's constant demands for troops and grain, his Egyptian subjects revolted in 486 BC. Whilst preparing to put down this revolt, Darius died, and was succeeded by his son Xerxes I; it now became his duty to punish the Greeks. Finally, at the end of the decade, in 480 BC, a massive second Persian invasion force would reach Greece, with Xerxes at its head. More united than ever before (though far from completely), partly as a result of the Athenians astonishing victory at Marathon, the Greeks were able to hold back and then defeat the Persians, with victories at Salamis and Plataea, and the famous last stand at Thermopylae [4].

Significance

Marathon was not a decisive victory over the Persians; they retained enough of an army and navy to have continued campaigning in Greece. Clearly, judging by the retreat to Asia, the Persian army and commanders were demoralised, and had no further desire to fight. The resources of the Persian empire were barely touched by the defeat at Marathon, and 10 years later a much larger Persian army would invade Greece[4]. However, it was the first time the Greeks had beaten the Persians, and showed them that the Persians were not invincible, and that resistance, rather than subjugation was possible. In short, "their victory endowed the Greeks with a faith in their destiny that was to endure for three centuries, during which western culture was born".[5] John Stuart Mill's famous opinion was that "the Battle of Marathon, even as an event in British history, is more important than the Battle of Hastings".[6]

A major lesson for the Greeks was the military potential of the hoplite phalanx. This style had developed during internecine warfare amongst the Greeks; since each city-state fought in the same way, the advantages and disadvantages of the hoplite phalanx had not been obvious. Marathon was the first time a phalanx faced more lightly-armed troops, and revealed how effective the hoplites could be in battle[58]. The phalanx formation was still vulnerable to cavalry (the cause of much caution by the Greek forces at the Battle of Plataea), but used in the right circumstances, it was now shown to be a potentially devastating weapon[70]

A second legacy of Marathon was the double envelopment. Some argue that this was not a conscious tactic by the Greeks. Was it really "Cannae before Cannae?"[71] The exact thoughts of the Greek commanders obviously cannot be reconstructed. Since the Persian army was not encircled and many troops escaped, either the tactics were not especially successful; or alternatively double envelopment (as understood today) was not a direct aim of the Greek tactics. A second question is whether the tactical lessons of Marathon were widely understood at the time. The subsequent stasis in tactics in Ancient Greek warfare suggests that perhaps they were not. In contrast, the lessons of Cannae were clearly understood by the Romans, and changes to their fighting style were made almost immediately.[72] Cannae has thus remained as the prototype of a successful double envelopment.

Legacy

Legends associated with the battle

The most famous legend associated with Marathon is that of Pheidippides/Philippides bringing news from the battle, described in the next section.

However, Pheidippides run to Sparta to bring aid, has other legends associated with it. Herodotus mentions that Pheidippides was visited by the god Pan on his way to Sparta (or perhaps on his return journey).[19] Pan asked why the Athenians did not honor him and Pheidippides promised that they would do so from then on. After the battle, a temple was built to him, and a sacrifice was annually offered.[73]

Similarly, after the victory the festival of 'Agroteras Thusia', ('Thusia' means sacrifice) was held at Agrae near Athens, in honor of Artemis Agrotera, in fulfillment of a vow made by the city, before the battle, to offer in sacrifice a number of goats equal to that of the Persians slain in the conflict. The number was so great, it was decided to offer 500 goats yearly until the number was filled. Xenophon notes that at his time, 90 years after the battle, goats were still offered yearly.[74][75][76][77]

Plutarch mentions that the Athenians saw Theseus, the mythical hero of Athens leading the army in full battle gear in the charge against the Persians[78] and indeed he was depicted in the mural of the Poikele Stoa fighting for the Athenians, along with the twelve Olympian gods, and other heroes.[79] Pausanias tells us that those who fought at Marathon:

"They say too that there chanced to be present in the battle a man of rustic appearance and dress. Having slaughtered many of the foreigners with a plough he was seen no more after the engagement. When the Athenians made enquiries at the oracle the god merely ordered them to honor Echetlaeus (He of the Plough-tail) as a hero."[80]

Furthermore Pausanias mentions that at times ghosts were seen and heard to engage in battle in Marathon.[27]. Another tale from the conflict is of the dog of Marathon. Aelian relates that one hoplite brought his dog to the Athenian encampment. The dog followed his master to battle and attacked the Persians at his master's side. He also informs us that this dog is depicted in the mural of the Poikile Stoa.[81]

Marathon run

According to Herodotus, an Athenian runner named Pheidippides had run from Athens to Sparta to ask for assistance before the battle. Following the battle, the Athenian army marched the 25 or so miles back to Athens at a very high pace (considering the quantity of armour, and the fatigue after the battle), in order to head off Artaphernes's second force of Persians (presumably including the missing cavalry). They arrived back in the late afternoon, in time to see the Persian ships turn away from Athens, thus completing the Athenian victory [7].

Later, in popular imagination, these two events became confused with each other, leading to a legendary version of events. This myth has Pheidippides running from Marathon to Athens after the battle, to announce the Greek victory with the word "Nenikēkamen!" (Attic: Νενικήκαμεν (We were victorious!), whereupon he promptly died of exhaustion. Most accounts incorrectly attribute this story to Herodotus; however, the story first appears in Plutarch's On the Glory of Athens in the 1st century AD, who quotes from Heracleides of Pontus' lost work, giving the runner's name as either Thersipus of Erchius or Eucles.[82] Lucian of Samosata (2nd century AD) gives the story but names the runner Philippides (not Pheidippides).[83] It should be noted that in some medieval codices of Herodotus the name of the runner between Athens and Sparta before the battle is given as Philippides and in a few modern editions this name is preferred.[84]

When the idea of a modern Olympics became a reality at the end of the 19th century, the initiators and organizers were looking for a great popularizing event, recalling the ancient glory of Greece. The idea of organizing a 'marathon race' came from Michel Bréal, who wanted the event to feature in the first modern Olympic Games in 1896 in Athens. This idea was heavily supported by Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympics, as well as the Greeks.[85] This would echo the legendary version of events, with the competitors running from Marathon to Athens. So popular was this event that it quickly caught on, becoming a fixture at the Olympic games, with major cities staging their own annual events[85]. The distance eventually became fixed at 26 miles (42 km) and 325 yards (297 m), though for the first years it was variable, being around 25 miles (40 km) - the approximate distance from Marathon to Athens.[85]

References

- ↑ Holland, p182

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Holland, pp191-193

- ↑ Holland, pp195-197

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Persian Fire. Holland, T. Abacus, ISBN 978-0-349-11717-1

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 J.F.C. Fuller, A Military History of the Western World

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Biographical Dictionary of Literary Influences: The Nineteenth Century, 1800-1914. John Powell, Derek W. Blakeley, Tessa Powell. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001. ISBN 9780313304224

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Holland, pp198

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Herodotus V, 65 [1]

- ↑ Herodotus V, 96 [2]

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Holland, pp133-138

- ↑ Holland, p159

- ↑ Herodotus V, 97 [3]

- ↑ Holland, p160

- ↑ Holland, p168

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 43 [4]

- ↑ Herodotus VI 43-45 [5]

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Holland, pp178-179

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 94 [6]

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 19.7 Holland, pp187-190

- ↑ D.W. Olson et al., "The Moon and the Marathon", Sky & Telescope Sep. 2004, pp. 34—41.1

- ↑ Roberts, John (2005). (ed.). ed.. The Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World. USA/UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 448. ISBN 0-19-280145-7.

- ↑ Geddes & Grosset (2004), Ancient Greece: A History, New Lamark, Scotland: David Dale House, revised edition of Cotterill, H. B., [1913], Ancient Greece, George Harrap & Company, ISBN 1-84205-185-7 p267

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 Η Μάχη του Μαραθώνα, το λυκαυγές της κλασσικής Ελλάδος = The battle of Marathon, the dawn of classical Greece, Πόλεμος και ιστορία = War and History magazine, issue 26 January 2000, Communications Editions, Athens

- ↑ Pausianus; Desription of Greece X 20.2

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Justinus II, 9

- ↑ Cornelius Nepos; Miltiades V

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Pausianus; Desription of Greece I 32.3

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 42 [7]

- ↑ Holland, p254

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 95 [8]

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Cornelius Nepos; Miltiades IV

- ↑ Herodotus VII, 97 [9]

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Stecchini, Livio. "The Persian Wars". Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Green, The Greco-Persian Wars, p90

- ↑ Herodotus V, 31 [10]

- ↑ Herodotus, VI 94 [11]

- ↑ Plutarch; Ethics 305b

- ↑ Pausianus; Desription of Greece IV 22.5

- ↑ s.v. Hippias

- ↑ Plato; Menexenus, 240A

- ↑ Lysias; Funeral Oration, 21

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους (History of the Greek nation volume Β), Athens 1971

- ↑ Bengtson H., Griechische Geschichte Handbuch der Altertumswissenschaft III, 4. München 1969

- ↑ Paul K. Davis (1999). 100 Decisive Battles. Santa Barbara, California. ISBN 1-57607-075-1.

- ↑ Moerbeek, Martijn (1997). The battle of Issus, 333 BC. Universiteit Twente

- ↑ Busolt D. Griechichse Geschichte bis zur Schlacht bei Chaeroneia, vol I, Gotha 1893

- ↑ Glotz G., Roussel P., Cohen R., Histoire Grecque vol. I-IV, Paris 1948

- ↑ Η Μάχη του Μαραθώνα (The battle of Marathon),Istorikes Selides magazine, issue 3, October 2006

- ↑ Athen. Ein Neubegihn der Welt geschichte, Berlin 1993 p.242

- ↑ Herodotus IV, 30 [12]

- ↑ Garoufalis N. Demetrios Η Μάχη του Μαραθώνα, Η δόξα της οπλιτικής φάλαγγας = The battle of Marathon, the glory of the hoplitic phalanx, Στρατιωτική Ιστορία = Military History magazine, issue 13, September 1997, Periskopio Editions, Athens

- ↑ Martin, Thomas R. (2000). Ancient Greece from prehistoric to Hellinistic times. New Haven, New England: Yale University Press.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Herodotus VI, 113 [13]

- ↑ Cornelius Nepos, Miltiades VI

- ↑ Plutarch; Aristeides V

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 110 [14]

- ↑ Nikos Giannopoulos, Μαραθώνας 490 πΧ (Marathon 490 BC) in Στρατιωτική Ιστορία, Μεγάλες Μάχες, Μαραθώνας 490 π.Χ (Military history, Great Battles, Marathon 490 BC), Periskopio Editions, Athens, March 2006, p42

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Holland, pp194-197

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Herodotus VI, 114 [15]

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Herodotus VI, 117 [16]

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Herodotus VI, 115 [17]

- ↑ Siegel, Janice (August 2, 2005). "Dr. J's Illustrated Persian Wars". Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- ↑ Ctesias; Persica 24

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 118 [18]

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 116 [19]

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 120 [20]

- ↑ Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War II, 34

- ↑ translation by Major General Dimitris Gedeon, HEA

- ↑ 'Anthologiae Graecae Appendix, vol. 3, Epigramma sepulcrale 17

- ↑ Holland, pp344-352

- ↑ Christodoulou Demetrios, Η στρατιωτική ιστορία της αρχαίας Ελλάδος, μία άλλη προσέγγιση (=The military history of ancient Greece, another point of view), Στρατιωτική Ιστορία (=Military history) magazine, issue 20 April 1998, Periskopio Editions, Athens

- ↑ The Fall of Carthage, Goldsworthy, A.

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 105 [21]

- ↑ Plutarch, De Malignitate Herodoti, 26

- ↑ Xenophon; Anabasis III 2.12

- ↑ Aelian; Varia Historia II 25

- ↑ Aristophanes; Equites, 660.

- ↑ Plutarch; Theseus 35

- ↑ Pausanias; Description of Greece I 15.3

- ↑ Pausanias; Description of Greece I 32.5

- ↑ Aelian; De natura animalium VII, 38

- ↑ Plutarch; Moralia 347C

- ↑ Lucian; A slip of the tongue in Salutation, III

- ↑ Herodotus, Book VI Erato; Introduction, Translation and Comments by Gabriel Syntomoros, Zitros Editions 2006 p.341

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 85.2 http://aimsworldrunning.org/marathon_history.htm. Accessed 15/10/08

Sources

Primary sources

- Herodotus (484 BC-425 BC?), Ιστορίης Απόδειξης (The histories), Book VI

- Thucydides (ca 460 BC-ca 400 BC, Ξυγγραφη (The Peloponnesian Wars)

- Isocrates (436 BC-338 BC), Επιταφειος τοις Κορινθειοις βοηθοις (Funeral Oration)

- Plato (428 BC/427 BC–ca. 348 BC/347 BC), Μενέξενος (Menexenus)

- -Νόμοι (Laws)

- Xenophon (c. 427 BC–355 BC), Κυρου Ανάβασις (Anabasis)

- Aristotle (384 BC-322 BC), ΑΘηναιων Πολιτεια (The Athenian Constitution)

- Cornelius Nepos (ca. 100 BC- 24 BC), De Viris Illustribus (Lifes of the eminent commanders)

- Plutarch (46-127 AD), Βίοι Παραλληλοι (Parallel Lives), Theseus, Aristeides, Themistocles

- - Περί του Ηροδότου κακοηθείας (On the malice of Herodotus)

- Lucian (ca. 120 - ca. 180 AD), Ὑπὲρ τοῦ ἐν τῇ προσαγορεύσει πταίσματος (A slip in the tongue of salutation)

- Pausanias (2nd century AD), Ελλαδος Περιήγησις (Description of Greece)

- Claudius Aelianus (c. 175–c. 235 AD), Ποικιλη Ιστορια (Various history)

- Marcus Junianus Justinus (3rd century AD), Historiarum Philippicarum (Epitome of the Phillipic History of Pompeius Trogus)

- Photius c.820 - 893 AD, Μυριόβιβλον (Bibliotheca or Myriobiblon): Epitome of Περσικά (Persica) by Ctesias (4th century BC)

- Suda Dictionary (10th century AD)

Secondary sources

- Green, Peter (1996). The Greco-Persian Wars. University of California Press. ISBN 0520203135.

- Holland, Tom (2006). Persian Fire: The First World Empire and the Battle for the West. Abacus. ISBN 0385513119.

- Dr. Manousos Kampouris, Η Μάχη του Μαραθώνα, το λυκαυγές της κλασσικής Ελλάδος = The battle of Marathon, the dawn of classical Greece, Πόλεμος και ιστορία = War and History magazine, issue 26 January 2000, Communications editions, Athens

- Christian Meier, Athen. Ein Neubeginn der Weltgeschichte, Berlin 1993

- Busolt D. Griechichse Geschichte bis zur Schlacht bei Chaeroneia, vol I, Gotha 1893

- Glotz G., Roussel P., Cohen R., Histoire Grecque vol. I-IV, Paris 1948

- Bengtson H., Griechische Geschichte Handbuch der Altertumswissenschaft III, 4. München 1969

- Nikos Giannopoulos, Μαραθώνας 490 πΧ (Marathon 490 BC) in Στρατιωτική Ιστορία, Μεγάλες Μάχες, Μαραθώνας 490 π.Χ (Military history, Great Battles, Marathon 490 BC),Periskopio editions, Athens March 2006

- Garoufalis N. Demetrios Η Μάχη του Μαραθώνα, Η δόξα της οπλιτικής φάλαγγας = The battle of Marathon, the glory of the hoplitic phalanx, Στρατιωτική Ιστορία = Military History magazine, issue 13, September 1997, Perisopio editions, Athens

- Christodoulou Demetrios, Η στρατιωτική ιστορία της αρχαίας Ελλάδος, μία άλλη προσέγγιση (=The military history of Ancient Greece, another point of view), Στρατιωτική Ιστορία (=Military history) magazine, issue 20 April 1998, Periscopio editions Athens

- I. Kakrides, Οι αρχαίοι Έλληνες στην νεοελληνική λαική παράδοση (=The Ancient Greeks in modern Greek popular traditions), Athens 1989

- Martin, Thomas R. (2000). Ancient Greece from prehistoric to Hellinistic times. New Haven, New England: Yale University Press.

- UT, Knoxville (2007). Ancient Greece and Rome in battle modes.Love and romance

External links

- Battle of Marathon animated battle map by Jonathan Webb

- Livius, Battle of Marathon by Jona Lendering

- Black and white photo-essay of Marathon