Battle of Long Island

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle Pass area, also known as Flatbush Pass, in the area of modern-day Prospect Park and Green-Wood Cemetery. Etching, c.1792

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

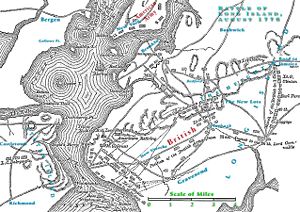

The Battle of Brooklyn, also known as the Battle of Long Island, fought on August 27, 1776, was the first major battle in the American Revolutionary War following the United States Declaration of Independence, the largest battle of the entire conflict, and the first battle an army of the United States ever engaged in.

The battle and its immediate aftermath were marked by the British capture of New York City (becoming the British military and political center of operations in North America for the remainder of the war), the execution of the American Nathan Hale, and the loss of nearly a quarter of the city's buildings in the Great Fire of New York. In the following weeks British forces occupied Long Island. However, General George Washington and his Continental Army escaped capture.

Contents |

Background

On March 17, 1776, the British fleet retreated to Halifax, Nova Scotia to refit after the end of the year-long Siege of Boston. Washington, who had successfully taken Boston, expected a new attack on New York. He moved his troops to Long Island and New York City, arrived himself on August 13, and reinforced fortifications there. General Charles Lee succinctly assessed the untenable situation of defending New York City without control of the sea, Washington's essential strategic error: "What to do with this city, I own, puzzles me," he wrote to Washington. "It is so encircled with deep navigable water that whoever commands the sea must command the town." Washington's inexperience led him astray: "Till of late," he wrote after the disaster, "I had no doubt in my own mind of defending this place."[5] On July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was ratified in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In the same month, British Lieutenant General Sir William Howe established his headquarters for their operation on Staten Island in New Dorp at the Rose and Crown tavern near the junction of present New Dorp Lane and Amboy Road which awaited reinforcement from his brother, Admiral Lord Howe.

Battle

On August 22, 1776, Colonel Edward Hand sent word to Lieutenant General George Washington that the British were preparing to cross The Narrows to Brooklyn from Staten Island.

Under the overall command of Howe, and the operational command of Major Generals Charles Cornwallis and Sir Henry Clinton, the British force numbered over 30,000. The British commenced their landing in Gravesend Bay, where, after having strengthened his forces for over seven weeks on Staten Island, Admiral Richard Howe moved 88 frigates. The British landed a total of 34,000 men south of Brooklyn. (This was a number greater than the combined population of Kings County and Manhattan as of 1771.[6])

About half of Washington's army, led by Major General Israel Putnam, was deployed to defend the village of Flatbush near Brooklyn while the rest held Manhattan. In a night march suggested and led by Clinton, the British forces used the lightly defended Jamaica Pass to turn Putnam's left flank. The following morning, American troops were attacked and fell back. Men under General William Alexander numbering about 400 fought a delaying action at the Old Stone House near the Gowanus Creek, attacking and counter-attacking a British artillery position there and sustaining over 50% casualties. This significantly aided the withdrawal of most of Washington's army to fortifications on Brooklyn Heights.

Later in the day, the British paused. This was not unusual in combat of the time, as horrendous casualties could result from point-blank musket fire and hand-to-hand combat; even the winner of such a battle could find himself unable to proceed. It was not uncommon for a commander, certain of the numerical and tactical superiority of his force, to offer a cornered enemy the option to surrender and thus avoid further bloodshed with the ultimate outcome of the battle certain. If formal surrender terms were not offered, the commander in a hopeless situation could at least be afforded an opportunity to consider his situation and, presumably, decide to surrender. It appears that this happened here; the British commanders surely remembered the Battle of Bunker Hill and the casualties they suffered in that pyrrhic victory.

During the night of August 29-August 30, 1776, having lost the battle, the Americans evacuated Long Island for Manhattan. Not wanting to have any more casualties, the Americans devised a plan. This evacuation of more than 9,000 troops required stealth and luck and the skill of Colonel John Glover and his 14th Continental Regiment from Marblehead, Massachusetts. It was not completed by sunrise as scheduled, and had a heavy fog not beset Long Island in the morning, the army may have been trapped between the British and the East River. However, the maneuver took the British by complete surprise. Even having lost the battle, Washington's withdrawal earned him praise from both the Americans and the British. Although the Americans lost the battle, Washington was able to rally his troops and fight the rest of the American Revolutionary War.

First-Hand Account

This letter was written from William Falconer to his brother on August 28, 1776:

August 28, 1776

Yesterday occurrences no doubt will be described to you various ways: I embrace this leisure moment to give as satisfactory an account as I am able. A large body of the enemy that landed some time since on Long Island, at the end of a beautiful plain, had extended their troops about six miles from the place of their first landing. - There were at this time eleven regiments of our troops posted in different parts of the woods, between our lines and the enemy, through which they must pass if they attempted any thing against us. Early in the morning our scouting parties discovered a large body of the enemy, both horse and foot, advancing on the Jamaica road towards us; I was dispatched to General Putnam, to inform him of it.

On my way back I discovered as I thought our battalion on a hill coming in, dressed in hunting shirts, and was going on to join them, but was stopped by a number of our soldiers, who told me they were the enemy in our dress - on this I prevailed on a sergeant and two men to halt and fire on them, which produced a shower of bullets, and we were obliged to retire.

In the mean time the enemy with a large body penetrated through the woods on our right, and center or front, and about nine o'clock landed another body on their right, the whole stretching across the fields and woods between our works and our troops, and sending out parties, accompanies with light horse, which harassed our surrounded and surprised new troops, who however sold their lives dear: Our forces then made towards our lines, but the enemy had taken possession of the ground before them by stolen marches. Our men broke through parties after parties, but still found the enemy thousands before them. Col. Smallwood, Atlee and Hazlet battalions, with General Stirling at their head, had collected on an eminence and made a good stand, but the enemy fired a field piece on them, and being greatly superior in number obliged them to retreat into a marsh, and finding it out of their power to withstand about 6000 men, they waded through the mud and water to a mill opposite them; their retreat was covered by the second battalion which had got into our lines. Col. Lutzand the New England regiments after this made some resistance in the woods, but were obliged by superior numbers to retire.

Colonel Miles and Broadhead battalions, finding themselves surrounded, determined to fight and run; they did son, and broke through English, Hessians, &c. and dispersed horse, and at last came in with considerable loss. Colonel Parry was early in the day shot through the head, encouraging his men. Eighty of our battalion came in this morning, having forced their way through the enemy rear, and came round by way of Hellgate; and we expect more, who are missing, will come in the same way.

Aftermath

Western Long Island

On September 11, 1776, the British received a delegation of Americans consisting of Benjamin Franklin, Edward Rutledge, and John Adams at the Conference House on the southwestern tip of Staten Island (known today as Tottenville) on the former estate of loyalist Christopher Billop. The peace conference failed as the Americans refused to revoke the Declaration of Independence. The terms were formally rejected on September 15.

On September 15, after heavily bombarding green militia forces, the British crossed to Manhattan, landed at Kip's Bay, and routed the Americans there as well. The following day, the two armies fought the Battle of Harlem Heights, resulting in a tactical draw. The Continental Army effectively abandoned Manhattan after devastating defeat at the Battle of Fort Washington. After a further battle at White Plains, Washington retreated across the Hudson to New Jersey. The British occupied New York City until 1783, when they evacuated the city as agreed in the Treaty of Paris,.[7]

On September 21, a fire broke out on Whitehall Street (widely believed to be at the Fighting Cocks Tavern) near the Battery in New York City. High winds carried it to nearly a quarter of the city's buildings, consuming 460-500 buildings. The British accused the rebels of setting the fire, although native New Yorkers instead blamed the British.

In the wake of the fire, Nathan Hale, a captain in the Connecticut Rangers, volunteered to enter New York in civilian clothes. Posing as a Dutch schoolteacher, Hale successfully gathered intelligence but was captured before he could return to the rebel lines. Hale was captured on September 21, 1776, and hanged the next day on the orders of Howe. According to legend, Hale uttered before being hanged, "I only regret that I have but one life to give my country".[8]

Eastern Long Island

While most of the battle was concentrated in western Long Island, within about 10 miles (16 km) of Manhattan, British troops were also deployed to the east to capture the entire 110 mile (180 km) length of Long Island to Montauk. The British met little or no opposition in this operation.

Henry B. Livingston was dispatched with 200 Continental troops to draw a line at what is now Shinnecock Canal at Hampton Bays to prevent the port of Sag Harbor from falling. Livingston, faced with insufficient manpower, abandoned Long Island to the British in September.

Residents of eastern Long Island were told to take a loyalty oath to the British government. In Sag Harbor, families met on September 14, 1776, to discuss the matter at the Sag Harbor Meeting House; 14 of the 35 families decided to evacuate to Connecticut.

The British planned to use Long Island as a staging ground for a new invasion of New England. They attempted to regulate ships going into Long Island Sound and blockaded Connecticut.

Casualties

The exact number of American soldiers who fought in the battle is unknown, but estimates are that there were at least 10,000, mostly New York militia reinforced from Connecticut, Delaware, and Maryland. Perhaps 1,407 Americans were wounded, captured, or missing, while 312 were killed. A British report claimed the capture of 89 American officers, including Colonel Samuel Miles, and 1,097 others.

Out of 32,000 British and Germans (including 9,000 Hessians) on Long Island, they sustained a total loss of 377. Five British officers and 58 men were killed, while 13 officers and 275 men were wounded or went missing. Of the Hessian forces under Carl von Donop, two were killed, and three officers and 23 men were wounded.

Monuments

Commemorations of the battle include:

- The Minerva Statue: The battle is commemorated with a statue of Minerva near the top of Battle Hill, the highest point of Brooklyn, in Green-wood Cemetery. The statue on the northwest corner of the cemetery looks toward the Statue of Liberty. In 2006, the statue was evoked in a successful defense to prevent a building from blocking the Manhattan view from the cemetery.

- The Prison Ship Martyrs' Monument: A freestanding Doric column in Fort Greene memorializing all those who died while kept prisoner on the British ships just off the shore of Brooklyn, in Wallabout Bay.

- The Old Stone House: A re-constructed farmhouse (c.1699) serves as a museum of the Battle of Long Island, also known as the "Battle of Brooklyn". It is located in J.J. Byrne Park, at 3rd Street and 5th Avenue, Brooklyn, situated within the boundaries of the original battle, and features models and maps.

- Prospect Park, Brooklyn, Battle Pass. Along the Eastern Side of Center Drive in Prospect Park, Brooklyn is a large granite boulder with a brass plaque affixed. The inscription reads:

'Historic Marker of Battle Pass. At this point the Old Porte Road or Valley Grove Road intersected the line of hills separating Flatbush from Brooklyn and Gowanus. In the Battle of Long Island, August 27, 1776, this pass was barricaded in front by Dongan Oak and other obstructions. It was protected by artillery on Redout [sic] Hill just to the east. Here the American forces stood their ground against the Hessians coming from the south till flanked from the river by a body of British troops. General Sullivan was captured, but most of his troops retreated across what is now the Long Meadow, joining the Maryland and other troops for the final resistance near the old stone house of Gowanus. A monument dedicated to the Soldiers from Maryland sits at the base of Lookout Hill, it reads "On this day what Brave Fellows I must lose" (General George Washington). '

Order of battle

- See Long Island order of battle

Notes

- ↑ The Battle of Brooklyn

- ↑ The Battle of Long Island

- ↑ The Battle of Long Island

- ↑ George! a Guide to All Things Washington By Frank E. Grizzard, Jr., Frank E. Grizzard pg. 204

- ↑ Charles Francis Adams, "The Battle of Long Island" The American Historical Review 1.4 (July 1896:650-670) p. 650-51.

- ↑ Greene and Harrington (1932). American Population Before the Federal Census of 1790. New York., as cited in: Rosenwaike, Ira (1972). Population History of New York City. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. pp. p.8. ISBN 0815621558.

- ↑ The removal was long celebrated in the city as Evacuation Day.

- ↑ For the authenticity of the saying, see Nathan Hale.

References

- John Gallagher; The Battle of Brooklyn 1776; 1995; 2002 Castle Press edition, ISBN 0-7858-1663-1.

- Schecter, Barnet. The Battle for New York (2002)

- Britishbattles.com - The Battle of Long Island 1776

- David Smith; New York 1776, The Continentals first battle; Osprey Campaign Series #192; Osprey Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978 1 84603 285 1.

External links

- The Battle of Long Island

- The Wild Geese Today Honoring Those who saved Washington's Army website with connections to articles on Maryland And Delaware line

- Website on Battle of Long Island

- "The Old Stone House" museum http://www.theoldstonehouse.org/ and http://www.google.com

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||