Battle of Iwo Jima

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

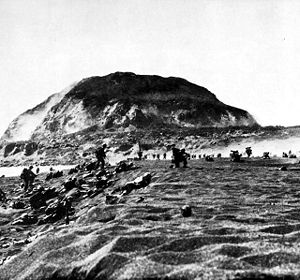

The Battle of Iwo Jima (February 19, 1945 – March 26, 1945), or Operation Detachment, was when the United States fought and captured the island of Iwo Jima from Japan, which produced some of the fiercest fighting in the Pacific Campaign of World War II.

The Japanese positions on the island were heavily fortified, with vast bunkers, hidden artillery, and 18 kilometers (11 mi) of underground tunnels.[3][4] The battle was the first American attack on the Japanese Home Islands and the Imperial soldiers defended their positions tenaciously. Of the 22,000 Japanese soldiers present at the beginning of the battle, over 20,000 were killed and only 1,083 taken prisoner.[1] The U.S. invasion, known as Operation Detachment, was charged with the mission of capturing the airfields on Iwo Jima.[1]

The battle was immortalized by Joe Rosenthal's photograph of the raising of the U.S. flag atop the 166 meter (546 ft) Mount Suribachi by five Marines and one Navy Corpsman. The photograph records the second flag-raising on the mountain, which took place on the fifth day of the 35-day battle. The picture became the iconic image of the battle and has been heavily reproduced.[5]

Contents |

Background

After the American seizure of the Marshall Islands and devastating air attacks against Truk in the Caroline Islands in February 1944 the Japanese military leadership reappraised the military situation. All indications pointed to an American drive towards the Marianas and Carolines. To counter such a move they established an inner line of defense extending generally northward from the Carolines to the Marianas, and thence to the Ogasawara Islands. In March 1944 the Thirty-First Army, commanded by General Hideyoshi Obata, was activated for the purpose of garrisoning this inner line. The commander of the Chichi Jima garrison was placed nominally in command of Army and Navy units in the Ogasawara Islands.[1]

Following the American seizure of bases in the Marshalls in the battles of Kwajalein and Eniwetok in February 1944 both Army and Navy reinforcements were sent to Iwo Jima. Five hundred men from the naval base at Yokosuka and an additional 500 from Chichi Jima reached Iwo Jima during March and April 1944. At the same time, with the arrival of reinforcements from Chichi Jima and the home islands, the Army garrison on Iwo Jima had reached a strength of over 5,000 men, equipped with 13 artillery pieces, 200 light and heavy machine guns, and 4,552 rifles. In addition there were numerous 120 mm coastal artillery guns, twelve heavy anti-aircraft guns, and thirty 25 mm dual-mount anti-aircraft guns.[1]

The loss of the Marianas during the northern summer of 1944 greatly increased the importance of the Ogasawaras for the Japanese, who were well aware that the loss of these islands would facilitate American air raids against the home islands, disrupting war manufacturing and severely damaging civilian morale.[1]

Final Japanese plans for the defense of the Ogasawaras were overshadowed by the fact that the Imperial Japanese Navy had already lost most of its strength and could no longer prevent American landings. Moreover, aircraft losses throughout 1944 had been so heavy that, even if war production were not affected by American air attacks, combined Japanese air strength was not expected to increase to 3,000 aircraft until March or April 1945. Even then, these planes could not be used from bases in the home islands against Iwo Jima because their range did not exceed 900 km (559 miles); besides, all available aircraft had to be hoarded for possible use on Taiwan and adjacent islands near land bases.[1]

In a postwar study, Japanese staff officers described the strategy applied in the defense of Iwo Jima in the following terms:

In the light of the above situation, seeing that it was impossible to conduct our air, sea, and ground operations on Iwo Jima toward ultimate victory, it was decided that in order to gain time necessary for the preparation of the Homeland defence, our forces should rely solely upon the established defensive equipment in that area, checking the enemy by delaying tactics. Even the suicidal attacks by small groups of our Army and Navy airplanes, the surprise attacks by our submarines, and the actions of parachute units, although effective, could be regarded only as a strategical ruse on our part. It was a most depressing thought that we had no available means left for the exploitation of the strategical opportunities which might from time to time occur in the course of these operations.

Daily bomber raids from the Marianas hit the mainland as part of Operation Scavenger. Iwo Jima served as an early warning station which radioed reports of incoming bombers back to mainland Japan, allowing Japanese air defenses to be prepared for the arrival of American bombers.[1]

At the end of the Battle of Leyte in the Philippines the Allies were left with a two month lull in their operations prior to the planned invasion of Okinawa. Iwo Jima was strategically important: it provided an airbase for Japanese aircraft to intercept long-range B-29 bombers and provided a haven for Japanese naval units in dire need of any support available. The capture of Iwo Jima would eliminate these problems and provide a staging area for the eventual invasion of the Japanese mainland. The distance of B-29 raids would be nearly halved, and a base would be available for P-51 Mustang fighters to escort and protect the devastating bomber raids. Intelligence sources were confident that Iwo Jima would fall in five days, unaware that the Japanese were preparing a quintessentially defensive posture, radically departing from any of their previous tactics. So successful was the Japanese preparation that it was discovered after the battle that the hundreds of tons of Allied bombs and thousands of rounds of heavy naval gunfire left the Japanese defenders almost unscathed and ready to wreak losses on the U.S. Marines unparalleled up to that point in the Pacific War. In the light of the optimistic intelligence reports, the decision was made to invade Iwo Jima: the landing was designated Operation Detachment.[1]

Planning and preparation

By June 1944, Lieutenant General Tadamichi Kuribayashi was assigned to command the defense of Iwo Jima. While drawing inspiration from the defense in the Battle of Peleliu, he designed a defense that broke with Japanese military doctrine. Rather than contest a beach landing, Kuribayashi ordered the creation of strong, mutual supporting positions in depth utilized the advantages of being in a defensive position to use static and heavy weapons such as heavy machine guns, while Colonel Baron Takeichi Nishi's tanks were used as camouflaged artillery positions. Kuribayashi organized the southern area of the island around Mount Suribachi as a semi-independent sector, while the main defensive line was built in the north. The nearly constant American naval and air bombardment further prompted the creation of an extensive system of tunnels that crisscrossed the island and were all connected, so that a pillbox that had been cleared could be reoccupied by Japanese soldiers. The network of bunkers and pillboxes greatly favored the defender. Hidden artillery and mortar positions along with land mines were placed all over the island. Kuribayashi also received a handful of Kamikaze pilots to use against the American fleet. 300 American navy seamen were killed by kamikazes throughout the battle. Against his wishes, Tokyo also forced Kuribayashi to erect beach defenses, the bulk of which were destroyed in the opening hours of the battle. Kuribayashi knew that Japan could not win, but he hoped to inflict massive casualties on the American forces, so that the United States would reconsider an invasion of the Japanese main islands.

The American plan of attack was relatively straightforward. The 4th and 5th Marine Divisions were to land on the south-eastern beach and initially focus on securing Mount Suribachi, the southern airfields and the west coast. Once this was completed, the line, reinforced by the 3rd Marine Division, would swing and advance to the northeast.

Invasion

At 02:00 on February 19, battleship guns signaled the commencement of the invasion of Iwo Jima. American naval craft used nearly everything available in their arsenal to shell the island, from the main guns to the antiaircraft flak cannons to the newly developed rockets. Soon thereafter, 100 bombers attacked the island, followed by another volley from the naval guns.[6] Although the bombing was consistent, it did not deter the Japanese defenses, since most of the Japanese positions were well-fortified and protected from shelling. Many were sheltered by Mount Suribachi itself, as the Japanese had spent the months prior to the invasion creating an elaborate system of tunnels and firing positions that ran throughout the entire mountain. For instance, some of the Japanese heavy artillery were concealed by reinforced steel doors in massive chambers built inside of Suribachi, which were nearly impenetrable to projectiles from the American bombardment.[6]

At 08:59, one minute ahead of schedule, the first of an eventual 30,000 Marines of the 3rd, 4th, and 5th Marine Divisions, under V Amphibious Corps, landed on the beach.[6] The initial wave was not hit by Japanese fire for quite some time; it was the plan of Japanese General Kuribayashi to hold fire until the beach was full of Marines and equipment.[6] Many of the Marines who landed on the beach in the first wave speculated that perhaps the naval artillery and air bombardment of the island had killed all of the Japanese troops that were expected to be defending the island.[1] In the deathly silence, they became somewhat unnerved as Marine patrols began to advance inland in search of the Japanese positions.[1]

Only after the front wave of Marines reached a line of Japanese bunkers defended by machine gunners did they take hostile fire. Many cleverly concealed Japanese bunkers and firing positions suddenly lit up and the first wave of Marines took devastating blows as rows upon rows of men were mowed down by the machine guns.[6] Aside from the Japanese defenses situated on the actual "beaches", the Marines faced heavy fire from Mount Suribachi at the south of the island. It was extremely difficult for the Marines to advance because of the inhospitable terrain, which consisted of volcanic ash. This ash allowed for neither a secure footing nor the construction of defensive foxholes to protect the Marines from hostile fire. However, the ash did help to absorb a portion of the fragments that were expelled by the Japanese artillery.[6] The Japanese heavy artillery in Suribachi would open their reinforced steel doors to fire and then immediately close their doors following to prevent counterfire from the American forces. This made it extremely difficult for American units to destroy a piece of Japanese artillery.[6]

To make matters worse for the American troops, the bunkers were connected to the elaborate tunnel system so that bunkers that were cleared with flamethrowers and grenades became operational shortly after Marines had declared them "cleared." These reactivated bunkers caused many additional casualties among them as Marines walking past these bunkers did not expect them to suddenly become hostile again.[6] The Marines advanced slowly while taking heavy machine gun and artillery fire. Due to the arrival of armored units, and heavy naval artillery and air units maintaining a heavy base of fire on Suribachi, the Marines were eventually able to advance past the beaches.[6] 760 Marines made a near-suicidal charge across to the other side of Iwo Jima that day. They took heavy casualties, but they made a considerable advance. By the evening the mountain had been cut off from the rest of the island, and 30,000 Marines had landed. About 40,000 more would follow.[6]

In the days after the landings, the Marines expected a banzai attack during the night. This had been the standard Japanese final defense strategy in previous battles against enemy ground forces in the Pacific (such as the Battle of Saipan), during which the majority of the Japanese attackers would be killed and the Japanese strength greatly reduced. However Kuribayashi had strictly forbidden banzai charges because he considered them futile.[6]

The fighting was extremely fierce. The Americans' advance was stalled by numerous defensive positions augmented by artillery, where they were ambushed by Japanese troops that occasionally sprung out of tunnels. The Marines learned that firearms were relatively ineffective against the Japanese defenders and effectively used flamethrowers and grenades to flush out Japanese troops in the tunnels. One of the technological innovations of the battle, the eight Sherman M4A3R3 medium tanks equipped with the Navy Mark I flame thrower ("Ronson" or Zippo Tanks), proved very effective at clearing Japanese positions. The Shermans were difficult to disable, such that defenders were often compelled to assault them in the open, where the Japanese troops would fall victim to the superior numbers of Marines.[6]

Close air support was initially provided by fighters from escort carriers off the coast. This shifted over to the 15th Fighter Group, flying P-51 Mustangs, after they arrived on the island on March 6. Similarly, illumination rounds (flares) which were used to light up the battlefield at night were initially provided by ships, shifting over later to landing force artillery. Navajo code talkers were part of the American ground communications, along with walkie-talkies and SCR-610 backpack radio sets.[6]

After running out of most water, food, and supplies, the Japanese troops became desperate towards the end of the battle. Kuribayashi, who had argued against banzai attacks at the start of the battle, realized that Japanese defeat was imminent. Marines began to face increasing numbers of nighttime attacks; these were only repelled by a combination of machine gun defensive positions and artillery support. At times, the marines engaged in hand-to-hand fighting to repel the Japanese attacks.[6]

With the landing area secure, more troops and heavy equipment came ashore and the invasion proceeded north to capture the airfields and the remainder of the island. Most Japanese soldiers fought to the death.[6]

Raising the flag

"Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima" is a historic photograph taken on February 23, 1945, by Joe Rosenthal. It depicts five United States Marines and a U.S. Navy corpsman raising the flag of the United States atop Mount Suribachi.[5] The photograph was extremely popular, being reprinted in thousands of publications. Later, it became the only photograph to win the Pulitzer Prize for Photography in the same year as its publication, and ultimately came to be regarded as one of the most significant and recognizable images of the war, and possibly the most reproduced photograph of all time.[5] Of the six men depicted in the picture, three (Franklin Sousley, Harlon Block, and Michael Strank) did not survive the battle; the three survivors (John Bradley, Rene Gagnon, and Ira Hayes) became celebrities upon the publication of the photo. The picture was later used by Felix de Weldon to sculpt the USMC War Memorial, located adjacent to Arlington National Cemetery just outside Washington, D.C.[5]

By morning of the fifth day of the battle (February 23), Mount Suribachi was effectively cut off from the rest of the island—above ground. By then, the Marines knew that the Japanese defenders had an extensive network of below-ground defenses, and knew that in spite of its isolation above ground, the volcano was still connected to Japanese defenders via the tunnel network. They expected a fierce fight for the summit. Two four-man patrols were sent up the volcano to reconnoiter routes on the mountain's north face. Popular legend (embroidered by the press in the aftermath of the release of the famous photo "Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima") has it that the Marines fought all the way up to the summit. But although the American riflemen were tensed for an ambush, none materialized. The Marines did encounter small groups of Japanese defenders on Suribachi, but the majority of the Japanese troops stayed underground in the tunnel network. The Japanese that did attack, attacked in small numbers and were generally all killed. The patrols made it to the summit and scrambled down again. They reported the lack of enemy contact to Colonel Chandler Johnson.[6]

Johnson then called for a platoon of Marines to climb Suribachi. With them, he sent a small American flag to fly if they reached the summit. Again, Marines began the ascent, expecting to be ambushed at any moment. And again, the Marines reached the top of Mount Suribachi without incident. Using a length of pipe they found among the wreckage atop the mountain, the Marines hoisted the U.S. flag over Mount Suribachi, the first foreign flag to fly on Japanese soil.[7] A photograph of this "first flag raising" was taken by photographer Louis R. Lowery. As the flag went up, Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal had just landed on the beach at the foot of Mount Suribachi. He decided that he wanted the flag as a souvenir. Popular legend has it that Colonel Johnson wanted the flag for himself. In fact, he believed that the flag belonged to the 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines, who had captured that section of the island. He sent Sergeant Mike Strank (who was photographed in the Flag Raising picture) to take a second (larger) flag up the volcano to replace the first. As the first flag came down, the second went up. It was after the second flag went up that Rosenthal took the famous photograph "Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima" of the replacement flag being planted on the mountain's summit.

Northern Iwo Jima

Despite the loss of Mount Suribachi on the south end of the island, the Japanese still held strong positions on the north end. Remaining under the command of Kuribayashi was the equivalent of eight infantry battalions, a tank regiment, two artillery, and three heavy mortar battalions. Also he had about 5,000 gunners and naval infantry. The struggle to take the Motoyama Plateau, including "Turkey Knob," took nearly three weeks. The Japanese actually had the Marines outgunned in this area, and the extensive network of tunnels allowed the Japanese to reappear in areas thought to have been cleared and therefore "safe".

On the night of March 25, a 300-man Japanese force launched a final counterattack in the vicinity of Airfield Number 2. Army pilots, Seabees and Marines of the 5th Pioneer Battalion and 28th Marines fought the Japanese force until morning but suffered heavy casualties (more than 100 Americans were killed and another 200 were wounded). The island was officially declared "secured" by the U.S. command the following day.

Although still a matter of speculation because of conflicting accounts from surviving Japanese veterans, it has been said that Kuribayashi led this final assault,[1] which unlike the loud banzai charge of previous battles, was characterised as a silent attack. If ever proven true, Kuribayashi would have been the highest ranking Japanese officer to have personally led an attack during World War II. Additionally, this would also be Kuribayashi's final act of departure from the normal practice of the commanding Japanese officers committing seppuku behind the lines while the rest perished in the banzai charge, as happened during the battles of Saipan and Okinawa.

Aftermath

Of the over 22,000 Japanese soldiers entrenched on the island, 20,703 died either from fighting or by ritual suicide. Only 1,083 were captured during the battle. The Allied forces suffered 27,909 casualties, with 6,825 killed in action. The number of American casualties was greater than the total Allied casualties on D-Day (estimated at 10,000, with 125,847 American casualties during the entire Operation Overlord).[8] Iwo Jima was also the only U.S. Marine battle where the American casualties exceeded the Japanese.[9] Some 300 Navy seamen were also killed.[1] Because all the civilians had been evacuated, there were no civilian casualties at Iwo Jima, unlike at Saipan and Okinawa.[10]

After Iwo Jima was declared secured, the Marines estimated there were no more than three hundred Japanese left alive in the island's warren of caves and tunnels. In fact, there were close to three thousand. The Japanese bushido code of honor, coupled with effective propaganda which portrayed American G.I.'s as ruthless animals, prevented surrender for many Japanese soldiers. Those who could not bring themselves to commit suicide hid in the caves during the day and came out at night to prowl for provisions. Some did eventually surrender and were surprised that the Americans often received them with compassion, offering water, cigarettes, or coffee.[11] The last of these stragglers, two of Lieutenant Toshihiko Ohno's men, Yamakage Kufuku and Matsudo Linsoki, lasted six years without being caught and finally surrendered in 1951[12] (another source gives the date of surrender as January 6, 1949).[13]

Strategic importance

Given the number of casualties, the necessity and long-term significance of the island's capture to the outcome of the war was a contentious issue from the beginning, and remains disputed. As early as April 1945 retired Chief of Naval Operations, William V. Pratt, asked in Newsweek magazine about the

expenditure of manpower to acquire a small, God-forsaken island, useless to the Army as a staging base and useless to the Navy as a fleet base ... [one] wonders if the same sort of airbase could not have been reached by acquiring other strategic localities at lower cost.[14]

The Japanese on Iwo Jima had radar and were thus able to notify their comrades at home of incoming B-29 Superfortresses flying from the Mariana Islands. Fighter aircraft based on Iwo Jima sometimes attacked these planes, which were especially vulnerable on their way to Japan because they were heavily laden with bombs and fuel. Although the island was used as an air-sea rescue base after its seizure, the traditional justification for Iwo Jima's strategic importance to the United States' war effort has been that it provided a landing and refueling site for American bombers on missions to and from Japan. As early as March 4, 1945, while fighting was still taking place, the B-29 bomber Dinah Might of the USAAF 9th Bomb Group reported it was low on fuel near the island and requested an emergency landing. Despite enemy fire, the airplane landed on the Allied-controlled section of the island, without incident, and was serviced, refueled and departed. In all, 2,251 B-29 Superfortress landings on Iwo Jima were recorded during the war.

None of these calculations played much if any of a role in the original decision to invade, however, which was almost entirely based on the Army Air Force's belief that the island would be a useful base for long-range fighter escorts. These escorts proved both impractical and unnecessary, and only ten such missions were ever flown from Iwo Jima.[15] Other justifications are also debatable. Although some Japanese interceptors were based on Iwo Jima, their impact on the American bombing effort was marginal; in the three months before the invasion only 11 B-29s were lost as a result.[16] The Superfortresses found it unnecessary to make any major detour around the island.[17] The capture of Iwo Jima did not affect the Japanese early-warning radar system, which continued to receive information on incoming B-29s from the island of Rota (which was never attacked).[18]

Some downed B-29 crewmen were saved by air-sea rescue aircraft and vessels operating from the island, but Iwo Jima was only one of many islands that could have been used for such a purpose. As for the importance of the island as a landing and refueling site for bombers, Marine Captain Robert Burrell, then a history instructor at the United States Naval Academy, suggested that only a small proportion of the 2,251 landings were for genuine emergencies, the great majority possibly being for minor technical checkups, training, or refueling. According to Burrell,

this justification became prominent only after the Marines seized the island and incurred high casualties. The tragic cost of Operation Detachment pressured veterans, journalists, and commanders to fixate on the most visible rationalization for the battle. The sight of the enormous, costly, and technologically sophisticated B-29 landing on the island's small airfield most clearly linked Iwo Jima to the strategic bombing campaign. As the myths about the flag raisings on Mount Suribachi reached legendary proportions, so did the emergency landing theory in order to justify the need to raise that flag.[19]

Nevertheless, in promoting his expanded exploration of the issue, The Ghosts of Iwo Jima, Burrell's publishers also point out that the very losses formed the basis for a "reverence for the Marine Corps" that not only embodied the "American national spirit" but ensured the "institutional survival" of the Marine Corps.[20]

Legacy

The United States Navy has commissioned several ships of the name USS Iwo Jima.

On February 19, 1985, the 40th anniversary of the landings, an event called the "Reunion of Honor" was held. The veterans of both sides who fought in the battle of Iwo Jima attended the event. The place was the invasion beach where U.S. forces landed. A memorial on which writings were engraved by both sides was built at the center of the meeting place. Japanese attended at the mountain side, where the Japanese writing was carved, and Americans attended at the shore side, where the English writing was carved. After unveiling and offering of flowers were made, the representatives of both countries approached the memorial; upon meeting, they shook hands. The old soldiers embraced each other and cried.

The combined Japan-U.S. memorial service of the 50th anniversary of the battle was held in front of the monument in February 1995. Further memorial services have been held on later anniversaries.

Medal of Honor awards

The Medal of Honor is the highest military decoration awarded by the United States government. It is bestowed on a member of the United States armed forces who distinguishes himself "…conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while engaged in an action against an enemy of the United States…" Because of its nature, the medal is commonly awarded posthumously. Since its creation during the American Civil War it has only been presented 3,464 times.

During this 1-month-long battle, 27 U.S. military personnel were awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions, 14 of them posthumously. Of the 27 medals awarded, 23 were presented to Marines and four were presented to United States Navy sailors; this is a full 30% of the 82 Medals of Honor awarded to Marines in the entirety of World War II.[21]

Movies and documentaries

- To the Shores of Iwo Jima, a 1945 American documentary produced by the United States Navy, Marine Corps and the Coast Guard.

- Glamour Gal, a 1945 film about Marine artillery

- Sands of Iwo Jima, a 1949 American film starring John Wayne.

- The Outsider, a 1961 film starring Tony Curtis as the conflicted flag raiser Ira Hayes.[22]

- Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima are two films directed by Clint Eastwood. Flags of Our Fathers is filmed from the American perspective and is based on the book by James Bradley and Ron Powers (Flags of Our Fathers). Letters from Iwo Jima (originally titled Red Sun, Black Sand) is filmed from the Japanese perspective.

See also

- List of Naval and land based operations in Pacific Theater during WW2

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 Morison, Samuel Eliot (2002) [1960]. Victory in the Pacific, 1945. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252070658. OCLC 49784806.

- ↑ Ross, Bill D. (1985). Iwo Jima: Legacy of Valor. New York: Vintage Books. p. XIV.

- ↑ "Letters from Iwo Jima". World War II Multimedia Database.

- ↑ "Battle of Iwo Jima — Japanese Defense". World War II Naval Strategy.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Landsberg, Mitchell. "Fifty Years Later, Iwo Jima Photographer Fights His Own Battle", Associated Press. Retrieved on September 11, 2007.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 Allen, Robert E. (2004). The First Battalion of the 28th Marines on Iwo Jima: A Day-by-Day History from Personal Accounts and Official Reports, with Complete Muster Rolls. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0786405600. OCLC 41157682.

- ↑ "Charles Lindberg, 86; Marine helped raise first U.S. flag over Iwo Jima", The Los Angeles Times (June 26, 2007), p. B8. Retrieved on November 30, 2008.

- ↑ "D-Day and the Battle of Normandy: Your Questions Answered Written by the D-Day Museum, Portsmouth". Portsmouth City Council. Retrieved on 2007-06-21.

- ↑ O'Brien, Cyril J.. "Iwo Jima Retrospective". Retrieved on 2007-06-21.

- ↑ "Selected March Dates of Marine Corps Historical Significance". History Division, United States Marine Corps. Retrieved on 2007-09-11.

- ↑ Toland, John (1970). The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945. New York: Random House. p. 731. OCLC 105915.

- ↑ Toland, p. 737

- ↑ Cook, Donald. "Capture of Two Holdouts January 6, 1949". No Surrender: Japanese Holdouts. Retrieved on 2007-09-11.

- ↑ Pratt, William V. (April 2, 1945). "What Makes Iwo Jima Worth the Price", Newsweek, p. 36.

- ↑ Assistant Chief of Air Staff (September-October 1945). "Iwo, B-29 Haven and Fighter Springboard", Impact, pp. 69–71.

- ↑ Craven, Wesley Frank; James Lea Cate (1953). The Army Air Forces in World War II. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 5:581–82. OCLC 704158.

- ↑ Craven and Cate, 5:559.

- ↑ Joint War Planning Committee 306/1, "Plan for the Seizure of Rota Island," January 25, 1945.

- ↑ Burrell, Robert S. (October 2004). "Breaking the Cycle of Iwo Jima Mythology: A Strategic Study of Operation Detachment". The Journal of Military History 68 (4): 1143–1186. doi:. OCLC 37032245. ISSN 1543-7795.

- ↑ "The Ghosts of Iwo Jima". Texas A&M University Press (2006). Retrieved on 2007-07-14.

- ↑ "U.S. Army Center of Military History Medal of Honor Citations Archive". Medal Of Honor Statistics (July 16, 2007). Retrieved on 2008-03-06.

- ↑ "Outsider (1961)". imdb. Retrieved on 2008-01-02.

Books

- Allen, Robert E. (2004). The First Battalion of the 28th Marines on Iwo Jima: A Day-by-Day History from Personal Accounts and Official Reports, with Complete Muster Rolls. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0786405600. OCLC 41157682.

- Bradley, James; Ron Powers (2001) [2000]. Flags of Our Fathers. New York: Bantam. ISBN 055338029X. OCLC 48215748.

- Bradley, James (2003). Flyboys: A True Story of Courage. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0316105848. OCLC 52071383.

- Buell, Hal (2006). Uncommon Valor, Common Virtue: Iwo Jima and the Photograph that Captured America. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 0425209806. OCLC 65978720.

- Burrell, Robert S. (2006). The Ghosts of Iwo Jima. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 1585444839. OCLC 61499920.

- Hammel, Eric (2006). Iwo Jima: Portrait of a Battle: United States Marines at War in the Pacific. St. Paul, Minn.: Zenith Press. ISBN 0760325200. OCLC 69104268.

- Hearn, Chester (2003). Sorties into Hell: The Hidden War on Chichi Jima. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0275980812. OCLC 51968985.

- Kakehashi, Kumiko (2007). So Sad to Fall in Battle: An Account of War Based on General Tadamichi Kuribayashi's Letters from Iwo Jima. Presidio Press. ISBN 0891419179.

- Kirby, Lawrence F. (1995). Stories From The Pacific: The Island War 1942-1945. Manchester, Mass.: The Masconomo Press. ISBN 0964510316. OCLC 32971472.

- Leckie, Robert (2005) [1967]. The Battle for Iwo Jima. New York: ibooks, Inc. ISBN 1590192419. OCLC 56015751.

- Lucas, Jack; D. K. Drum (2006). Indestructible: The Unforgettable Story of a Marine Hero at the Battle of Iwo Jima. Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306814706. OCLC 68175700.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (2002) [1970]. Victory in the Pacific, 1945, vol. 14 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252070658. OCLC 49784806.

- Newcomb, Richard F.; Harry Schmidt (2002) [1965]. Iwo Jima. New York: Owl Books. ISBN 0805070710. OCLC 48951047.

- Overton, Richard E. (2006). God Isn't Here: A Young American's Entry into World War II and His Participation in the Battle for Iwo Jima. Clearfield, Utah: American Legacy Media. ISBN 0976154706. OCLC 60694955.

- Ross, Bill D. (1986) [1985]. Iwo Jima: Legacy of Valor. New York: Vintage. ISBN 0394742885. OCLC 13582622.

- Shively, John C. (2006). The Last Lieutenant: A Foxhole View of the Epic Battle for Iwo Jima. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253347289. OCLC 61761637.

- Toyn, Gary W. (2006). The Quiet Hero: The Untold Medal of Honor Story of George E. Wahlen at the Battle for Iwo Jima. Clearfield, Utah: American Legacy Media. ISBN 0976154714. OCLC 72161745.

- Veronee, Marvin D. (2001). A portfolio of photographs : selected to illustrate the setting for my experience in the battle of Iwo Jima, World War II, Pacific theater. Quantico: Visionary Pub.. ISBN 0971592829. OCLC 52001277.

- Wells, John K. (1995). Give Me Fifty Marines Not Afraid to Die: Iwo Jima. Abilene, Tex.: Quality Publications. ISBN 096446750X. OCLC 32153036.

- Wheeler, Richard (1994) [1980]. Iwo. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1557509220. OCLC 31693687.

- Wheeler, Richard (1994) [1965]. The Bloody Battle for Suribachi. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1557509239. OCLC 31970164.

- Wright, Derrick (2007) [1999]. The Battle of Iwo Jima 1945. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0750945443. OCLC 67871973.

Further reading

- Alexander, Col. Joseph H., USMC (Ret). (1994). Closing In: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima. Marines in World War II Commemorative Series. Washington, D.C.: History and Museums Division, Headquarters, United States Marine Corps. OCLC 32194668. http://www.nps.gov/wapa/indepth/extContent/usmc/pcn-190-003131-00/index.htm.

- Bartley, LtCol. Whitman S., USMC (1954). Iwo Jima: Amphibious Epic. Marines in World War II Historical Monograph. Washington, D.C.: Historical, Division of Public Information, Headquarters, United States Marine Corps. OCLC 28592680. http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/USMC-M-IwoJima/index.html.

- Garand, George W.; Truman R. Strobridge (1971). "Part VI: Iwo Jima". Western Pacific Operations. Volume IV of History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Historical Branch, United States Marine Corps. http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/IV/USMC-IV-VI-1.html.

External links

- "Animated Map History of The Battle of Iwo Jima (including Medal of Honor citations)". HistoryAnimated.com.

- "The Battle for Iwo Jima (color combat footage)". SonicBomb.com.

- Brady, John H.. "Iwo Jima". Iwo Jima, Inc..

- "Battle of Iwo Jima". WW2DB.com. Site contains 220 photographs.

- Williams, Greg. "Dimensions of Valor" (Flash). Tampa Tribune. TBO.com. 3-D Stereo Photograph of Iwo Jima Flag-raising.

- "Mt. Suribachi HDR Image". Japan Photos (February 2007). A tone-mapped High Dynamic Range Image of Iwo Jima.

- "Iwo Jima: Forgotten Valor". Primary Source Adventures. Portal to Texas History, University of North Texas.

- Dawson, Rick (2007). "The Battle of Iwo Jima". ArticleMyriad.com.

- "Iwo Jima Combat Footage in Color". WW2incolor.com.

- Lemer, Jeremy (February 15, 2005). "Remembering the Battle of Iwo Jima". Retrieved on October 6, 2006.

- "Operations map of Iwo Jima" (JPG) (October 23, 1944).

- "Collection of military maps of Iwo Jima". Historical Resources (September 15, 2008).

- "To the Shores of Iwo Jima" (Video). Google Video.

- "Battle of Iwo Jima". History of War.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||