Battle of Arras (1917)

| Battle of Arras | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of World War I | |||||||

The Town Square, Arras, France. February, 1919. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

• • Canada • • • |

• • |

||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

Edmund Allenby, Hubert Gough, Henry Horne |

Ludwig von Falkenhausen, Georg von der Marwitz |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 27 divisions in the assault | 7 divisions in the line, 27 divisions in reserve |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~160,000† | ~120,000–160,000† | ||||||

| † Discussed in detail in Casualties, below | |||||||

|

|

|||||

The Battle of Arras was a British offensive during World War I. From 9 April to 16 May, 1917, British, Canadian, and Australian troops attacked German trenches near the French city of Arras on the Western Front.

For much of the war, the opposing armies on the Western Front were at a stalemate, with a continuous line of trenches stretching from the Belgian coast to the Swiss border.[1] In essence, the Allied objective from early 1915 was to break through the German defences into the open ground beyond and engage the numerically inferior German army in a war of movement.[2] The Arras offensive was conceived as part of a plan to bring about this result.[3] It was planned in conjunction with the French High Command, who were simultaneously embarking on a massive attack (the Nivelle Offensive) about eighty kilometres to the south.[3] The stated aim of this combined operation was to end the war in forty-eight hours.[4] At Arras, the British Empire's immediate objectives were more modest: (1) to draw German troops away from the ground chosen for the French attack and (2) to take the German-held high ground that dominated the plain of Douai.[3]

Initial efforts centred on a relatively broad-based assault between Vimy in the northwest and Bullecourt in the southeast. After considerable bombardment, Canadian troops advancing in the north were able to capture the strategically significant Vimy Ridge, and British divisions in the centre were also able to make significant gains. Only in the south, where British and Australian forces were frustrated by the elastic defence, were the attackers held to minimal gains. Following these initial successes, British forces engaged in a series of small-scale operations to consolidate the newly won positions. Although these battles were generally successful in achieving limited aims, many of them resulted in relatively large numbers of casualties.[3]

When the battle officially ended on 16 May, British Empire troops had made significant advances, but had been unable to achieve a major breakthrough at any point.[3] Experimental tactics—for instance, the creeping barrage, the graze fuze, and counter-battery fire—had been battle-tested, particularly in the first phase, and had demonstrated that set-piece assaults against heavily fortified positions could be successful. This sector then reverted to the stalemate that typified most of the war on the Western Front.

Contents |

Prelude

At the beginning of 1917, the British and French were still searching for a way to achieve a strategic breakthrough on the Western Front.[2] The previous year had been marked by the costly failure of the British offensive along the Somme river, while the French had been unable to take the initiative due to intense German pressure at Verdun.[2] Both confrontations consumed enormous quantities of resources while achieving virtually no strategic gains.[2] This impasse reinforced the French and British commanders' belief that to end the stalemate they needed a breakthrough.[2] However, while this desire may have been the main impetus behind the offensive, the timing and location were heavily influenced by a number of political and tactical factors.[4]

Political background

The mid-war years were momentous times. Politicians in Paris and London were under great pressure from the press, the people and their parliaments to bring the war to a close.[5] The casualties from the battles of Gallipoli, the Somme and Verdun had been high and there was little prospect of victory in sight. The British prime minister, H. H. Asquith, resigned in early December 1916 and was succeeded by the "Welsh wizard", David Lloyd-George.[5] In France, premier Aristide Briand, with the redoubtable General (later Marshal) Hubert Lyautey as Minister of Defence, were politically diminished and would soon, in March 1917, resign.[6]

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, the United States was close to declaring war on Germany.[7] American public opinion was growing increasingly incensed by a long succession of high-profile U-boat attacks upon civilian shipping, starting with the sinking of RMS Lusitania in 1915 and culminating in the torpedoing of seven American merchantmen in early 1917.[7] The United States Congress finally declared war on Imperial Germany on 6 April 1917, but it would be more than a year before a suitable army could be raised, trained, and transported to France.[7]

Strategic background

Although the French and British had intended to launch a 1917 spring assault, two developments put the plan in jeopardy. First, in February, Russia declined to commit to a joint offensive, meaning that the planned two-front offensive would be reduced to a French-only assault along the River Aisne. Second, the German Army began to retreat and consolidate its positions along the Hindenburg line, thus disrupting the tactical assumptions underlying the plans for the French offensive.[6] In fact, until French troops advanced to compensate during the Battles of Arras, they encountered no German troops in the planned assault sector. Given these factors, it was initially uncertain whether the offensive would go forward. The existing French government desperately needed a victory to avoid major civil unrest at home, but the British were wary of proceeding in view of the rapidly changing tactical situation.[6] However, in a meeting with David Lloyd George, French commander-in-chief General Nivelle was able to convince the British Prime Minister that, if the British launched a diversionary assault to draw German troops away from the Aisne sector, the French offensive could succeed. It was agreed that the French assault on the Aisne would go forward in mid-April, and that the British would make a diversionary attack in the Arras sector approximately one week prior.[6]

Opposing forces

Three Allied armies were already concentrated in the Arras sector. They were deployed, roughly north to south, as follows: the First Army under Horne, the Third Army under Allenby, the Fifth Army under Gough. The overall British commander was Field-Marshal Sir Douglas Haig and the battle plan was devised by General Allenby.[8]. Unusually in that war, three Scottish divisions (all of Third Army) were grouped within close proximity of each other for the start of the attack:- the 15th Scottish Division of VI Corps and 9th Scottish Division and 51st Highland Division of XVII Corps. The strongly Scottish-influenced 34th Division was also positioned in the midst of their Scottish XVII Corps neighbours.

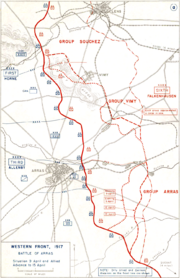

Facing the Allied forces were two German armies: the Sixth Army under 73-year-old General von Falkenhausen and the Second Army under General von der Marwitz (who was recovering from an illness he had contracted on the Eastern Front). The armies had been organised into three groups – Gruppe Souchez, Gruppe Vimy, and Gruppe Arras – deployed in that order north to south.[9] However, only seven German Divisions were in the line; their remaining divisions were in reserve, to reinforce or to counterattack as required.[10]

General von Falkenhausen reported directly to General Erich Ludendorff, operational chief of the German High Command (the Oberste Heeresleitung, or OHL). Ludendorff's staff contained several highly innovative and extremely capable officers, notably Major Georg Wetzell, Colonel Max Bauer, and Captain Hermann Geyer.[11] Since December 1916, Ludendorff's staff had been developing counter-tactics to oppose the new Allied tactics that had earlier been used at the Somme and Verdun. Although these battles proved extremely costly for the Allied Powers, they also seriously weakened the German army. In early 1917 the German army was instructed to implement these counter-tactics (the Elastic Defence); Falkenhausen's failure to do so would prove disastrous.[11]

Preliminary phase

The British plan was well developed, drawing on the lessons of the Somme and Verdun of the previous year. Rather than attacking on an extended front, the full weight of artillery would be concentrated on a relatively narrow stretch of twenty-four miles. The barrage was planned to last about a week at all points on the line, with a much longer and heavier barrage at Vimy to weaken its strong defences.[12] During the assault, the troops would advance in open formation, with units leapfrogging each other in order to allow them time to consolidate and regroup. Before the action could be undertaken, a great deal of preparation was required, much of it innovative.

Mining and tunnelling

Since October 1916, the Royal Engineers had been working underground to construct tunnels for the troops.[12] The Arras region is chalky and therefore easily excavated; under Arras itself is a vast network (called the boves) of caverns, underground quarries, galleries and sewage tunnels. The engineers devised a plan to add new tunnels to this network so that troops could arrive at the battlefield in secrecy and in safety.[12] The scale of this undertaking was enormous: in one sector alone four Tunnel Companies (of 500 men each) worked around the clock in 18-hour shifts for two months. Eventually, they constructed 20 kilometres of tunnels, graded as subways (foot traffic only); tramways (with rails for hand-drawn trollies, for taking ammunition to the line and bringing casualties back from it); and railways (a light railway system).[12] Just before the assault the tunnel system had grown big enough to conceal 24,000 men, with electric lighting provided by its own small powerhouse, as well as kitchens, latrines, and a medical centre with a fully equipped operating theatre.[13][14][15] The bulk of the work was done by New Zealanders, including Maori and Pacific Islanders from the New Zealand Pioneer battalion,[13] and Bantams from the mining towns of Northern England.[12]

Assault tunnels were also dug, stopping a few metres short of the German line, ready to be blown open by explosives on Zero-Day.[12] In addition to this, conventional mines were laid under the front lines, ready to be blown immediately before the assault. Many were never detonated for fear that they would churn up the ground too much. In the meantime, German sappers (military engineers) were actively conducting their own underground operations, seeking out Allied tunnels to assault and counter-mine.[12] Of the New Zealanders alone, 41 died and 151 were wounded as a result of German counter-mining.[13]

Most of the tunnels and trenches are currently off-limits to the public for reasons of safety. A 250 metre portion of the Grange Subway at Vimy Ridge is open to the public from May through November and the Wellington tunnel was opened to the public as the Carrière Wellington museum in March 2008.[16][17]

Battle in the air

Dominance of the air space over Arras was essential for artillery spotting, and photography of trench systems.[18] These were controlled and coordinated by the 1st Field Survey Company, Royal Engineers.[19] Aerial observation was hazardous work as, for best results, the aircraft had to fly at slow speeds and low altitude over the German defences. It became even more dangerous with the arrival of the "Red Baron", Manfred von Richthofen, with his highly-experienced and better-equipped "Flying Circus" in March 1917. Its deployment led to sharply increased casualty rates among Allied pilots and April 1917 was to become known as Bloody April. One German infantry officer later wrote "during these days, there was a whole series of dogfights, which almost invariably ended in defeat for the British since it was Richthofen's squadron they were up against. Often five or six planes in succession would be chased away or shot down in flames".[20] The average flying life of a Royal Flying Corps pilot in Arras in April was 18 hours.[18] Between 4 April – 8 April, the Royal Flying Corps lost 75 aircraft in combat, with the loss of 105 aircrew.[18] The casualties created a pilot shortage and replacements were sent to the front straight from flying school: during the same period, 56 aircraft were crashed by inexperienced RFC pilots.[18]

Creeping barrage

To keep enemy action to a minimum during the assault, a "creeping barrage" was planned.[21] This requires gunners to lay down a screen of high explosive and shrapnel shells that creeps across the battlefield about one hundred metres in advance of the assaulting troops.[21] The Allies had previously used creeping barrages at the battles of Neuve Chapelle and the Somme but had encountered two technical problems. The first was accurately synchronising the movement of the troops to the fall of the barrage: for Arras, this was overcome by rehearsal and strict scheduling. The second was the barrage falling erratically as the barrels of heavy guns degrade swiftly but at differing rates during fire: for Arras, the rate of degradation of each gun barrel was calculated individually and each gun calibrated accordingly. While there was a risk of friendly fire, the creeping barrage forced the Germans to remain in their trenches, allowing Allied soldiers to advance without fear of machine gun fire.[21] Additionally, new instantaneous fuses (the graze fuze) had been developed for high explosive shells so that they detonated on the slightest impact, vaporising barbed wire.[21] Poison gas shells were used for the final minutes of the barrage.[21]

Counter-battery fire

The principal danger to assaulting troops came from enemy artillery fire as they crossed no man's land, accounting for over half the casualties at the first day of the Somme. A further complication was the location of German artillery, hidden as it was behind the ridges. In response, specialist artillery units were created specifically to attack German artillery. Their targets were provided by 1st Field Survey Company, Royal Engineers,[22] who collated data obtained from "flash spotting" and "sound ranging". (Flash spotting required Royal Flying Corps observers to record the location of telltale flashes made by guns whilst firing.[19] Sound ranging used a matrix of microphones to triangulate the location of a gun from the sound it made during firing.)[19] On Zero-Day, 9 April, over 80% of German heavy guns in the sector were neutralised (that is, "unable to bring effective fire to bear, the crews being disabled or driven off") by counter-battery fire.[22] Gas shells were also used against the draught horses of the batteries and to disrupt ammunition supply columns.[23]

First phase

The preliminary bombardment of Vimy Ridge started on 20 March; and the bombardment of the rest of the sector on 4 April.[12] Limited to a front of only 24 miles (39 km), the bombardment used 2,689,000 shells,[23] over a million more than had been used on the Somme.[6] German casualties were not heavy but the men became exhausted by the endless task of keeping open dug-out entrances and demoralised by the absence of rations caused by the difficulties of preparing and moving hot food under bombardment.[23] Some went without food altogether for two or three consecutive days.[23]

By the eve of battle, the front-line trenches had effectively ceased to exist and their barbed wire defences were blown to pieces.[23] The official history of the 2nd Bavarian Reserve Regiment describes the front line as "consisting no longer of trenches but of advanced nests of men scattered about".[23] The 262nd Reserve Regiment history writes that its trench system was "lost in a crater field".[23] To add to the misery, for the last ten hours of bombardment, gas shells were added.[24]

Zero-Hour had originally been planned for the morning of 8 April (Easter Sunday), but it was pushed back 24 hours at the request of the French, despite relatively good weather in the assault sector. Zero-Day was rescheduled for 9 April with Zero-Hour at 05:30. The assault was immediately preceded by an exceedingly intense hurricane bombardment lasting five minutes, following a relatively quiet night.[23]

When the time came, it was snowing heavily; and Allied troops advancing across no man's were hindered by large drifts. It was still dark and visibility on the battlefield was incredibly poor.[24] A westerly wind was at the Allied soldiers' backs blowing "a squall of sleet and snow into the faces of the Germans".[23] The combination of the unusual bombardment and poor visibility meant many German troops were caught unawares and taken prisoner, still half-dressed, clambering out of the deep dug-outs of the first two lines of trenches.[23] Others were captured, without their boots, trying to escape but stuck in the knee-deep mud of the communication trenches.[23]

First Battle of the Scarpe

9 - 14 April 1917

The major British assault of the first day was directly east of Arras, with the 12th Division attacking Observation Ridge, north of the Arras—Cambrai road.[24] After reaching this objective, they were to push on towards Feuchy, as well as the second and third lines of German trenches. At the same time, elements of the 3rd Division began an assault south of the road, with the taking of Devil's Wood, Tilloy-lès-Mofflaines and the Bois des Boeufs as their initial objectives.[24] The ultimate objective of these assaults was the Monchyriegel, a trench running between Wancourt and Feuchy, and an important component of the German defences.[24] Most of these objectives, including Feuchy village, had been achieved by the evening of 10 April though the Germans were still in control of large sections of the trenches between Wancourt and Feuchy, particularly in the area of the heavily fortified village of Neuville-Vitasse.[24] The following day, troops from the 56th Division were able to force the Germans out of the village, although the Monchyriegel was not fully in British hands until a few days later.[24] The British were able to consolidate these gains and push forward towards Monchy-le-Preux, although they suffered heavy casualties in fighting near the village.[25]

One reason for the success of the offensive in this sector was the failure of German commander von Falkenhausen to employ Ludendorff's new innovation, the Elastic Defence.[26] In theory, the enemy would be allowed to make initial gains, thus stretching their lines of communication. Reserves held close to the battlefield would be committed once the initial advance had bogged down, before enemy reinforcements could be brought up. The defenders would thus be able to counterattack and regain any lost territory. In this sector, however, von Falkenhausen kept his reserve troops too far from the front, and they were unable to arrive in time for a useful counterattack on either 10 or 11 April.[26]

Battle of Vimy Ridge

9 - 12 April 1917

At roughly the same time, in perhaps the most carefully crafted portion of the entire offensive, the Canadian Corps launched an assault on Vimy Ridge. Advancing behind a creeping barrage, and making heavy use of machine guns – eighty to each brigade, including one Lewis gun in each platoon – the corps was able to advance through about 4,000 yards (3,700 m) of German defences, and captured the crest of the ridge at about 13:00.[27] Military historians have attributed the success of this attack to careful planning by Canadian Corps commander Julian Byng, constant training, and the assignment of specific objectives to each platoon.[27] By giving units specific goals, troops could continue the attack even if their officers were killed or communication broke down, thus bypassing two major problems of combat on the Western Front.[27]

First Battle of Bullecourt

10 - 11 April 1917

South of Arras, the plan called for two divisions, the British 62nd Division and the Australian 4th Division to attack either side of the village of Bullecourt and push the Germans out of their fortified positions and into the reserve trenches.[28] The attack was initially scheduled for the morning of 10 April, but the tanks intended for the assault were delayed by bad weather and the attack was postponed for 24 hours. The order to delay did not reach all units in time, and two battalions of the West Yorkshire Regiment attacked and were driven back with significant losses.[28] Despite protests from the Australian commanders, the attack was resumed on the morning of 11 April; mechanical failures meant that only 11 tanks were able to advance in support, and the limited artillery barrage left much of the barbed wire in front of the German trenches uncut. Additionally, the abortive attack of the previous day alerted German troops in the area to the impending assault, and they were better prepared than they had been in the Canadian sector.[29] Misleading reports about the extent of the gains made by the Australians deprived them of necessary artillery support and, although elements of the 4th Division briefly occupied sections of German trenches, they were ultimately forced to retreat with heavy losses.[29] In this sector, the German commanders correctly employed the Elastic Defence and were therefore able to counterattack effectively.[30]

Second phase

After the territorial gains of the first two days, a hiatus followed as the immense logistical support needed to keep armies in the field caught up with the new realities. Battalions of pioneers built temporary roads across the churned up battlefield; heavy artillery (and its ammunition) was manhandled into position in new gun pits; food for the men and feed for the draught horses was brought up, and casualty clearing stations were established in readiness for the inevitable counterattacks. Allied commanders also faced a dilemma: whether to keep their exhausted divisions on the attack and run the risk of having insufficient manpower or replace them with fresh divisions and lose momentum.[31]

In London, The Times[32], commented: "the great value of our recent advance here lies in the fact that we have everywhere driven the enemy from high ground and robbed him of observation. [H]aving secured these high seats [Vimy, Monchy and Croisailles] and enthroned ourselves, it is not necessarily easy to continue the rapid advance. An attack down the forward slope of high ground, exposed to the fire of lesser slopes beyond, is often extremely difficult and now on the general front. . . there must intervene a laborious period, with which we were familiar at the Somme, of systemic hammering and storming of individual positions, no one of which can be attacked until some covering one has been captured".

The German press reacted similarly. The Vossische Zeitung, a Berlin daily newspaper, wrote: "We have to count on reverses like that near Arras. Such events are a kind of tactical reverse. If this tactical reverse is not followed by strategical effects i.e., breaking through on the part of the aggressor, then the whole battle is nothing but a weakening of the attacked party in men and materiel."[33] The same day, the Frankfurter Zeitung commented: "If the British succeed in breaking through it will render conditions worse for them as it will result in freedom of operations which is Germany's own special art of war".[33]

General Ludendorff however was less sanguine. The news of the battle reached him during his 52nd birthday celebrations at his headquarters in Kreuznach.[34] He wrote: "I had looked forward to the expected offensive with confidence and was now deeply depressed".[34] He telephoned each of his commanders and "gained the impression that the principles laid down by OHL were sound. But the whole art of leadership lies in applying them correctly".[34] (A later court of enquiry would establish that Falkenhausen had indeed misunderstood the principles of the Elastic Defence.) Ludendorff immediately ordered reinforcements.[27] Then, on 11 April, he sacked General von Falkenhausen's chief of staff and replaced him with his defensive line expert, Colonel Fritz von Lossberg.[11] Von Lossberg went armed with vollmacht (a power of attorney enabling him to issue orders in Ludendorff's name), effectively replacing Falkenhausen. Within hours of arriving, von Lossberg was restructuring the German defences.[34]

During the Second Phase, the Allies continued to press the attack east of Arras. Their aims were to consolidate the gains made in the first days of the offensive;[26] to keep the initiative,[11] and to break through in concert with the French at Aisne.[11] However, from 16 April onwards, it was apparent that the Nivelle Offensive was failing and Haig came under pressure to keep the Germans occupied in the Arras sector in order to minimise French losses.[29]

Battle of Lagnicourt

15 April 1917

Observing that the Australian 1st Division was holding a frontage of 13,000 yards (12,000 m), the local German Corps commander (General Otto Von Moser, commanding the German XIV Reserve Corps) planned a spoiling attack to drive back the advanced posts, destroy supplies and guns and then retire to the Hindenburg defences. Passing his plans to higher command, they assigned an extra division to his corps to further strengthen the attack.

Attacking with 23 battalions (from 4 divisions), the German forces managed to penetrate the Australian front line at the junction on the Australian 1st Division and Australian 2nd Division and occupy the village of Lagnicourt (damaging some Australian artillery pieces).

Counter-attacks from the Australian 9th and 20th Battalions restored the front line, and the action ended with the Australians suffering 1,010 casualties, against 2,313 German casualties.[35]

Second Battle of the Scarpe

23 - 24 April 1917

On 23 April, the British launched an assault east from Wancourt towards Vis-en-Artois. Elements of the 30th and the 50th Divisions made initial gains, and were in fact able to secure the village of Guémappe, but could advance no further east and suffered heavy losses.[36] Farther north, German forces counterattacked in an attempt to recapture Monchy-le-Preux, but troops from the Royal Newfoundland Regiment were able to hold the village until reinforcements from the 29th Division arrived.[36] British commanders determined not to push forward in the face of stiff German resistance, and the attack was called off the following day on 24 April.[36]

Battle of Arleux

28 - 29 April 1917

Although the Canadian Corps had successfully taken Vimy Ridge, difficulties in securing the south-eastern flank had left the position vulnerable. To rectify this, British and Canadian troops launched an attack towards Arleux-en-Gohelle on 28 April.[37] Arleux was captured by Canadian troops with relative ease, but the British troops advancing on Gavrelle met stiffer resistance from the Germans. The village was secured by early evening, but when a German counterattack forced a brief retreat, elements of the 63rd Division were brought up as reinforcements and the village was held. Subsequent attacks on 29 April however, failed to net any further advances.[37] Despite achieving the limited objective of securing the Canadian position on Vimy Ridge, casualties were high, and the ultimate result was disappointing.[30]

Second Battle of Bullecourt

3 - 17 May 1917

After the initial assault around Bullecourt failed to penetrate the German lines, British commanders made preparations for a second attempt. British artillery began an intense bombardment of the village, which, by 20 April, had been virtually destroyed.[38] Although the infantry assault was initially planned for 20 April, it was pushed back a number of times and finally set for the early morning of 3 May.[38] At 03:45, elements of the 2nd Division attacked east of Bullecourt village, intending to pierce the Hindenburg Line and capture Hendecourt-lès-Cagnicourt, while British troops from the 62nd Division attempted to capture Bullecourt itself.[39] German resistance was fierce, and, when the offensive was called off on 17 May, very few of the initial objectives had been met. The Australians were in possession of much of the German trench system between Bullecourt and Riencourt-lès-Cagnicourt, but had been unable to capture Hendecourt. To the west, British troops were ultimately able to push the Germans out of Bullecourt, but, in so doing, incurred considerable losses, failing also to advance north-east to Hendecourt.[40]

Third Battle of the Scarpe

3 - 4 May 1917

After securing the area around Arleux at the end of April, the British determined to launch another attack east from Monchy to try and breakthrough the Boiry Riegel and reach the Wotanstellung, a major German defensive fortification.[30] This was scheduled to coincide with the Australian attack at Bullecourt in order to present the Germans with a two–pronged assault. British commanders hoped that success in this venture would force the Germans to retreat further to the east. With this objective in mind, the British launched another attack near the Scarpe on 3 May. However, neither prong was able to make any significant advances and the attack was called off the following day after incurring heavy casualties.[30] Although this battle was a failure, the British learned important lessons about the need for close liaison between tanks, infantry, and artillery, which they would later apply in the Battle of Cambrai (1917).[30]

Aftermath

By the standards of the Western front, the gains of the first two days were nothing short of spectacular. A great deal of ground was gained for relatively few casualties and a number of strategically significant points were captured, notably Vimy Ridge. Additionally, the offensive succeeded in drawing German troops away from the French offensive in the Aisne sector.[27] In many respects, the battle might be deemed a victory for the British and their allies, but these gains were offset by high casualties and the ultimate failure of the French offensive at the Aisne. By the end of the offensive, the British had suffered more than 150,000 casualties and gained little ground since the first day.[26] Despite significant early gains, they were unable to effect a breakthrough, and the situation reverted to stalemate. Although historians generally consider the battle a British victory, in the wider context of the front, it had very little impact on the strategic or tactical situation.[26][27] Ludendorff later commented: no doubt exceedingly important strategic objects lay behind the British attack, but I have never been able to discover what they were.[34]

On the Allied side, twenty-five Victoria Crosses were subsequently awarded (see list). On the German side, on 24 April 1917, Kaiser Wilhelm awarded Von Lossberg the Oakleaves (similar to a bar for a repeat award) for the Pour le Mérite he had received at the Battle of the Somme the previous September.[41]

Casualties

The most quoted Allied casualty figures are those in the returns made by Lt-Gen Sir George Fowke, Haig's adjutant-general. His figures collate the daily casualty tallies kept by each unit under Haig's command.[42] Third Army casualties were 87,226; First Army 46,826 (including 11,004 Canadians at Vimy Ridge); and Fifth Army 24,608; totalling 158,660.[43] German losses by contrast are more difficult to determine. Gruppe Vimy and Gruppe Souchez suffered 79,418 casualties but the figures for Gruppe Arras are incomplete. Additionally, German records excluded those "lightly wounded".[44] Captain Cyril Falls (the British official battle historian) estimated that 30% needed to be added to German returns for comparison with the British.[44] Falls makes "a general estimate" that German casualties were "probably fairly equal".[44] Nicholls puts them at 120,000;[43] and Keegan at 130,000.[4]

Commanders

Although Haig paid tribute to Allenby for the plan's "great initial success,"[45] Allenby's subordinates "objected to the way he handled the. . . attritional stage." (He was sent to command the Egyptian Expeditionary Force in Palestine. He regarded the transfer as a "badge of failure" but he "more than redeemed his reputation by defeating" the Ottomans in 1917–18.)[45] Haig stayed in his post until the end of the war.

When it became apparent that a major factor in the British success was command failures within his own army, Ludendorff removed several staff officers, including General von Falkenhausen.[30] Falkenhausen was removed from the Sixth Army and never held a field command again. He spent the rest of war as Governor-General of Belgium. In early 1918, The Times carried an article – entitled Falkenhausen's reign of terror – describing 170 military executions of Belgian civilians that had taken place since he had been appointed governor.[46]

Ludendorff and Von Lossberg learned a major lesson from the battle. They discovered that although the Allies were capable of breaking through the front they could probably not capitalise on their success if they were confronted by a mobile, clever enemy.[47] Ludendorff immediately ordered training in war of movement tactics and manoeuvre for his counterattack divisions.[47] Von Lossberg was soon promoted to general and directed the German defence in Haig's Flanders offensives of the summer and late autumn. (Von Lossberg was later to become "legendary as the fireman of the Western Front; always sent by OHL to the area of crisis".[11])

See also

- List of Canadian battles during World War I

References

Notes

- ↑ Ashworth, 3–4

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Ashworth, 48–51

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Ashworth, 55–56

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Keegan (London), 348–352

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Keegan (London), 227–231

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Strachan, 243–244

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Keegan (London), 377–379

- ↑ Nicholls, 23

- ↑ Nicholls, 39

- ↑ Nicholson, Chap VIII

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Lupfer, Chap.1

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 Nicholls, 30–32

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 New Zealand Defence Force press release

- ↑ Tunnellers in Arras 2007-04-24

- ↑ "The Arras tunnels", NZ Ministry for Culture and Heritage, 2008-02-01

- ↑ Veterans Affairs Canada website

- ↑ Von Angelika Franz "Tunnelstadt unter der Hölle" Spiegel Online (German)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Nicholls, 36

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 History of the Defence Surveyors Association

- ↑ Jünger, p133

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Nicholls, 53–4

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Sheffield, 194

- ↑ 23.00 23.01 23.02 23.03 23.04 23.05 23.06 23.07 23.08 23.09 23.10 Wynne, 173–175

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 Oldham, 50–53.

- ↑ Oldham, 56.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Keegan (New York), 325–6

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 Strachan, 244–246

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Oldham, 66.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Liddell Hart

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 Oldham, 38–40

- ↑ Buffetaut, 84

- ↑ The Times, 20 April 1917, "Winning of the High Ground", p 6

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Quoted in The Times, 13 April 1917, page 6

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 Ludendorff 421–422

- ↑ Bean, Vol IV, Ch X

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Oldham, 60–62

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Online history of the Worcestershire Regiment.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Oldham, 69.

- ↑ Oldham, 60–70.

- ↑ Oldham, 71.

- ↑ Pour le Mérite online archive

- ↑ Preserved at the British Public Records Office

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Nicholls, 210–211

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Falls, cited by Nicholls, 211

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Sheffield & Bourne, 495–6

- ↑ The Times, 6 January 1918, page 9

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Buffetaut, 122

Bibliography

- Ashworth, Tony. Trench warfare 1914–1918. 2000: Macmillan Press, London. ISBN 0-330-48068-5

- Bean, C.E.W. Volume IV - The Australian Imperial Force in France: 1917, Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1933. OCLC 9945668

- Buffetaut, Yves. The 1917 Spring Offensives: Arras, Vimy, Le Chemin des Dames. Paris: Histoire et Collections, 1997. ISBN 2-908-182-66-1

- Falls, Cyril; Falls, Cyril Bentham; Becke, Archibald Frank; Edmonds, James E. Military Operations, France and Belgium, 1917: Vol II, The German Retreat to the Hindenburg Line and the Battles of Arras. London: Macmillan, 1940 (reprinted 1992) ISBN 0-901-62790-9

- Gilbert, Martin. First World War. London: HarperCollins, 1995. ISBN 978-000637666-8

- Holmes, Richard. The Western Front. London: BBC Publications, 1999. ISBN 978-157500147-0

- Jünger, Ernst. Storm of Steel (trans. Michael Hofman). Penguin Group: 2003. ISBN 978-014118691-7

- Keegan, John. The First World War. London: Pimlico, 1999. ISBN 978-071266645-9 OCLC 248608836

- Liddell Hart, Basil. The Real War, 1914–1918. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1930. OCLC 56212202

- Ludendorff, Erich. My War Memoirs. London: Naval & Military Press, 2005. ISBN 978-184574303-1

- Lupfer, Timothy T. The Dynamics of Doctrine: The Change in German Tactical Doctrine during the First World War. Kansas: Combat Studies Institute, 1981. Accessed 26 May 2007.

- New Zealand Defence Force. Arras Tunnellers Memorial (press release) Accessed 4 June 2007.

- Nicholls, Jonathon. Cheerful Sacrifice: The Battle of Arras 1917. Pen and Sword Books, 2005. ISBN 1-84415326-6

- Nicholson, G.W.L., Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War: Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1919. 1962. Queens Printer and Controller of Stationary, Ottawa, Canada. OCLC 55016603

- Oldham, Peter. The Hindenburg Line. Pen and Sword Books Ltd, 1997. ISBN 978-0850525687

- Reed, Paul. Walking Arras. Pen and Sword Books Ltd, 2007. ISBN 1844156192

- Sheffield, Gary. Forgotten Victory: The First World War - Myths and Realities. London: Review (Hodder), 2002. ISBN 978-074726460-6

- Sheffield, Gary & Bourne, John. Douglas Haig: War Diaries and Letters 1914–1918. UK: Wiedenfeld & Nicolson, 2005. ISBN 978-029784702-1

- Stokesbury, James L. A Short History of World War I. New York: Perennial, 1981. OCLC 6760776

- Strachan, Hew. The First World War. New York: Viking, 2003. OCLC 53075929

- Winkler, Gretchen & Tiedemann, Kurt M. von. Pour le Mérite Online Archive Accessed: 6 June 2007

- Wynne, G.C. If Germany Attacks: the Battle in Depth in the West, London: Faber, 1940. (Facsimile edition: West Point Military Library, 1973: ISBN 0-8371-5029-9)

External links

- Online history of the Worcestershire Regiment. General history of a regiment involved in the battle, accessed 4-24-2007.

- The Battle of Arras at 1914-1918.net. Online history of the battle, accessed 2007-04-04.

- The Battle of Arras at the War Chronicle. Another online history of the battle, accessed 4-16-2007.

- New Zealand Tunnellers Memorial in Arras

- The Arras tunnels - NZHistory.net.nz

- France reveals British WWI cave camp BBC News 5 May 2008