St. Peter's Basilica

| St. Peter's Basilica Basilica Sancti Petri (Latin) Basilica di San Pietro in Vaticano (Italian) |

|

The interior of St. Peter's Basilica by Giovanni Paolo Pannini |

|

| Basic information | |

|---|---|

| Location | Vatican City |

| Religious affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| Year consecrated | 1628 |

| Ecclesiastical status | Major basilica |

| Architectural description | |

| Architect(s) | Donato Bramante Antonio da Sangallo the Younger |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Architectural style | Renaissance and Baroque |

| Direction of facade | East |

| Year completed | 1626 |

| Construction cost | 46,800,052 ducats |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 60,000 + |

The Basilica of Saint Peter (Latin: Basilica Sancti Petri), officially known in Italian as the Basilica di San Pietro in Vaticano and commonly known as St. Peter's Basilica, is located within the Vatican City. It occupies a "unique position" as one of the holiest sites and as "the greatest of all churches of Christendom".[1][2][3] In Catholic Tradition, it is the burial site of its namesake Saint Peter, who was one of the twelve apostles of Jesus and, according to Tradition, was the first Bishop of Antioch, and later first Bishop of Rome and therefore first in the line of the papal succession. While St. Peter's is the most famous of Rome's many churches, it is not the first in rank, an honour held by the Pope's cathedral church, the Basilica of St. John Lateran. (See: Status)

Catholic Tradition holds that Saint Peter's tomb is below the altar of the basilica. For this reason, many Popes, starting with the first ones, have been buried there. There has been a church on this site since the 4th century. Construction on the present basilica, over the old Constantinian basilica, began on April 18, 1506 and was completed in 1626.[4]

St. Peter's is famous as a place of pilgrimage, for its liturgical functions and for its historical associations. It is associated with the papacy, with the Counter-reformation and with numerous artists, most significantly Michelangelo. As a work of architecture, it is regarded as the greatest building of its age.[5] Contrary to popular misconception, Saint Peter's is not a cathedral, as it is not the seat of a bishop. It is properly termed a basilica. Like all the earliest churches in Rome,[6] it has the entrance to the east and the apse at the west end of the building.

Contents

|

Status

The Basilica of St. Peter is one of four major basilicas of Rome, the others being the Basilica of St. John Lateran, Santa Maria Maggiore and St. Paul outside the Walls. It is the most prominent building inside the Vatican City. Its dome is a dominant feature of the skyline of Rome. Probably the largest church in Christianity,[7] it covers an area of 2.3 hectares (5.7 acres) and has a capacity of over 60,000 people. One of the holiest sites of Christendom in the Catholic Tradition, it is traditionally the burial site of its namesake Saint Peter, who was one of the twelve apostles of Jesus and, according to Roman Catholic Tradition, also the first Bishop of Antioch, and later first Bishop of Rome, the first Pope. Although the New Testament does not mention Peter's presence or martyrdom in Rome, Catholic tradition holds that his tomb is below the baldachin and altar; for this reason, many Popes, starting with the first ones, have been buried there. Construction on the current basilica, over the old Constantinian basilica, began on April 18, 1506 and was completed in 1626.[8]

Although the Vatican basilica is neither the Pope's official seat or first in rank among the great basilicas, (St. John Lateran) it is most certainly his principal church, as most Papal ceremonies take place at St. Peter's due to its size, proximity to the Papal residence, and location within the Vatican City walls. In the apse of the basilica is Bernini's monument enclosing the "Chair of St. Peter" or cathedra, sometimes presumed to have been used by Saint Peter himself, but which was a gift from Charles the Bald and used by various popes.[9]

History

Burial site of St. Peter

After the crucifixion of Jesus in the second quarter of the 1st century AD, it is recorded in the Biblical book of the Acts of the Apostles that one of his twelve disciples, Simon known as Peter, a fisherman from Galilee, took a leadership position among Jesus' followers and was of great importance in the founding of the Christian Church. The name Peter is "Petrus" in Latin and "Petros" in Greek, deriving from "petra" which means "stone" or "rock" in Greek. It is believed by a long tradition that Peter, after a ministry of about thirty years, traveled to Rome and met his martyrdom there.

According to the traditional story, Peter was executed in the year 64 A.D. during the reign of the Roman Emperor Nero. His execution was one of the many martyrdoms of Christians following the Great Fire of Rome. He was said to have been crucified head downwards, by his own request, near the obelisk in the Circus of Nero. This obelisk now stands in Saint Peter's Square and is revered as a "witness" to Peter's death. It is one of several ancient Obelisks of Rome.

The traditional story goes on to say that Peter's remains were buried just outside the Circus, on the Mons Vaticanus across the Via Cornelia from the Circus, less than 150 meters from his place of death. The Via Cornelia (which may have been known by another name to the ancient Romans) was a road which ran east-to-west along the north wall of the Circus on land now covered by the southern portions of the Basilica and Saint Peter's Square. Peter's grave was initially marked simply by a red rock, symbolic of his name, but meaningless to non-Christians. A shrine was built on this site some years later. Almost three hundred years later, Old Saint Peter's Basilica was constructed over this site. It is possible that the exact location of Peter's grave was known with certainty by Christians throughout all this time and that therefore the traditional location of Saint Peter's tomb is, in fact, its true location.

On December 23, 1950, in his pre-Christmas radio broadcast to the world, Pope Pius XII announced the discovery of Saint Peter's tomb.[10] This was the culmination of 10 years of archaeological research under the crypt of the basilica, an area inaccessible since the 9th century. The burial place appears to have been an underground vault, with a structure above it believed to have been built by Pope Anacletus in the 1st century. Human remains were discovered, but it could not be determined if they were, in fact, the bones of the Apostle Peter. Indeed, the area now covered by the Vatican City had been a cemetery for some years before the Circus of Nero was built. It was a burial ground for the numerous executions in the Circus and for many years after the burial of Saint Peter many Christians chose to be buried near him. It is likely that any excavation anywhere on the Vatican grounds would discover human remains.

Old St. Peter's

Old St. Peter's Basilica was the fourth century church begun by the Emperor Constantine between 326 and 333 AD. It was of typical basilical Latin Cross form with an apsidal end at the chancel, a wide nave and two aisles on either side. It was over 103.6 metres (350 ft) long and the entrance was preceded by a large colonnaded atrium. This church had been built over the small shrine believed to mark the burial place of St. Peter. It contained a very large number of burials and memorials, including those of most of the popes from St. Peter to the 15th century. Since the construction of the current basilica, the name Old St. Peter's Basilica has been used for its predecessor to distinguish the two buildings.[11]

The plan to rebuild

By the end of the 15th century, having been neglected during the period of the Avignon Papacy, the old basilica was in bad repair. It appears that the first pope to consider rebuilding, or at least making radical changes was Pope Nicholas V (1447 – 55). He commissioned work on the old building from Leone Battista Alberti and Bernardo Rossellino and also got Rossellino to design a plan for an entirely new basilica, or an extreme modification of the old. His reign was frustrated by political problems and when he died, little had been achieved. [12] He had, however, had 2,522 cartloads of stone transported from the Roman Colosseum.[13]

In 1505, Pope Julius II, failing to heed warnings that the death of Nicholas V was an omen to those who might interfere with St Peter's, in order to glorify Rome and also undoubtedly for his own self agrandizement,[5] made a decision to demolish the ancient building and replace with something grander. A competition was held, and a number of the designs have survived at the Uffizi Gallery. A succession of popes and architects followed in the next 120 years, their combined efforts resulting in the present building. The scheme begun by Julius II continued through the reigns of Leo X (1513 1521), Hadrian VI (1522 – 1523). Clement VII (1523 – 1534), Paul III (1534 – 1549), Julius III (1550 – 1555), Marcellus II (1555), Paul IV (1555 – 1559), Pius IV (1559 – 1565), Pius V (saint) (1565 – 1572), Gregory XIII (1572 – 1585), Sixtus V (1585 – 1590), Urban VII (1590), Gregory XIV (1590 – 1591), Innocent IX (1591), Clement VIII(1592 – 1605), Leo XI (1605), Paul V (1605 – 1621), Gregory XV (1621 – 1623), Urban VIII (1623 – 1644) and Innocent X (1644 – 1655).

Architecture

Successive plans

Pope Julius' scheme for the grandest building in Christendom[5] was the subject of a competition for which a number of entries remain intact in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. It was the design of Bramante that was selected, and for which the foundation stone was laid in 1506. This plan was in the form of an enormous Greek Cross with a dome inspired by that of the huge circular Roman temple, the Pantheon.[5] The main difference between Bramante's design and that of the Pantheon is that where the dome of the Pantheon is supported by a continuous wall, that of the new basilica was to be supported only on four large piers. This feature was maintained in the ultimate design. Bramante's dome was to be surmounted by a lantern with its own small dome but otherwise very similar in form to the Early Renaissance lantern of Florence Cathedral designed for Brunelleschi's dome by Michelozzo.[14]

Bramante had envisioned that the central dome be surrounded by five lower domes at the diagonal axes. The equal chancel, nave and transept arms were each to be of two bays ending in an apse. At each corner of the building was to stand a tower, so that the overall plan was square, with the apses projecting at the cardinal points. Each apse had two large radial buttresses, which squared off its semi-circular shape.[15]

When Pope Julius died in 1513, Bramante was replaced with Giuliano da Sangallo, Fra Giocondo and Raphael. Sangallo and Fra Giocondo both died in 1515, Bramante himself having died the previous year. The main change in Raphael's plan is the nave of five bays, with a row of complex apsidal chapels off the aisles on either side. Raphael's plan for the chancel and transepts made the squareness of the exterior walls more definite by reducing the size of the towers, and the semi-circular apses more clearly defined by encircling each with an ambulatory.[16]

In 1520 Raphael also died, aged 37, and his successor Peruzzi maintained changes that Raphael had proposed to the internal arrangement of the three main apses, but otherwise reverted to the Greek Cross plan and other features of Bramante.[17] This plan did not go ahead because of various difficulties of both church and state. In 1527 Rome was sacked and plundered by Emperor Charles V. Peruzzi died in 1536 without his plan being realised.[5]

At this point Antonio da Sangallo (known as "Sangallo the Younger") submitted a plan which combines features of Peruzzi, Raphael and Bramante in its design and extends the building into a short nave with a wide facade and portico of dynamic projection. His proposal for the dome was much more elaborate of both structure and decoration than that of Bramante and included ribs on the exterior. Like Bramante, Sangallo proposed that the dome be surmounted by a lantern which he redesigned to a larger and much more elaborate form.[18] Sangallo's main practical contribution was to strengthen Bramante's piers which had begun to crack.[19]

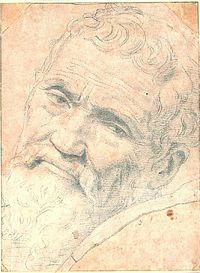

On January 1, 1547 in the reign of Pope Paul III, Michelangelo, then in his seventies, succeeded Sangallo the Younger as "Capomaestro", the superintendent of the building program at St Peter's.[20] It is he that is to be regarded as the principal designer of a large part of the building as it stands today, and as bringing the construction to a point where it could be carried through. He did not take on the job with pleasure; it was forced upon him by Pope Paul, frustrated at the death of his chosen candidate, Giulio Romano and the refusal of Sansovino to leave Venice. Michelangelo wrote "I undertake this only for the love of God and in honour of the Apostle." He insisted that he should be given a free hand to achieve the ultimate aim by whatever means he saw fit.[19]

Michelangelo's contribution

Michelangelo took over a building site at which four piers, enormous beyond any constructed since the days of Ancient Rome, were rising behind the remaining nave of the old basilica. He also inherited the numerous schemes designed and redesigned by some of the greatest architectural and engineering brains of the 16th century. There were certain common elements in these schemes. They all called for a dome to equal that engineered by Brunelleschi a century earlier and which has since dominated the skyline of Renaissance Florence, and they all called for a strongly symmetrical plan of either Greek Cross form, like the iconic St. Mark's Basilica in Venice, or of a Latin Cross with the transepts of identical form to the chancel as at Florence Cathedral.

Even though the work had progressed only a little in 40 years, Michelangelo did not simply dismiss the ideas of the previous architects. He drew on them in developing a grand vision. Above all, Michelangelo recognized the essential quality of Bramante's original design. He reverted to the Greek Cross and, as Helen Gardner expresses it: "Without destroying the centralising features of Bramante's plan, Michelangelo, with a few strokes of the pen converted its snowflake complexity into massive, cohesive unity."[21]

As it stands today, St. Peter's has been extended with a nave by Carlo Maderno. It is the chancel end (the ecclesiastical "Eastern end") with its huge centrally placed dome that is the work of Michelangelo. Because of its location within the Vatican State and because the projection of the nave screens the dome from sight when the building is approached from the square in front of it, the work of Michelangelo is best appreciated from a distance. What becomes apparent is that the architect has greatly reduced the clearly defined geometric forms of Bramante's plan of a square with square projections, and also of Raphael's plan of a square with semi-circular projections.[22] Michelangelo has blurred the definition of the geometry by making the external masonry of massive proportions and filling in every corner with a small vestry or stairwell. The effect created is of a continuous wall-surface that is folded or fractured at different angles, but lacks the right-angles which usually define change of direction at the corners of a building. This exterior is surrounded by a giant order of Corinthian pilasters all set at slightly different angles to each other, in keeping with the everchanging angles of the wall's surface. Above them the huge cornice ripples in a continuous band, giving the appearance of keeping the whole building in a state of compression.[23]

Dome- successive designs and final solution

The dome of St. Peter's rises to a total height of 136.57 m (448.06 ft) from the floor of the basilica to the top of the external cross. It is the tallest dome in the world.[24] Its internal diameter is 41.47 metres (136.06 ft), being just slightly smaller than two of the three other huge domes that preceded it, those of the Pantheon of Ancient Rome and Florence Cathedral of the Early Renaissance. It has a greater diameter by approximately 30 feet (9.1 m) than that of the third great dome, Constantinople's Hagia Sophia church, completed in 537. It was to the domes of the Pantheon and Florence duomo that the architects of St. Peter's looked for solutions as to how to go about building what was conceived, from the outset, as the greatest dome of Christendom.

Bramante and Sangallo

The dome of the Pantheon, 43.3 metres (142 ft), (the widest dome in the world until the 19th century), stands on a circular wall with no entrances or windows except a single door. The whole building is as high as it is wide. Its dome is constructed in a single shell of concrete, made light by the inclusion of a large amount of the volcanic stones tufa and pumice. The inner surface of the dome is deeply coffered which has the effect of creating both vertical and horizontal ribs, while lightening the overall load. At the summit is an ocular opening eight metres (27 ft) across which provides light to the interior.[5]

Bramante's plan for the dome of St. Peter's follows that of the Pantheon very closely, and like that of the Pantheon, was designed to be constructed in tufa concrete for which he had rediscovered a formula. With the exception of the lantern that surmounts it, the profile is very similar, except that in this case the supporting wall becomes a drum raised high above ground level on four massive piers. The solid wall, as used at the Pantheon, is lightened at St. Peter's by Bramante piercing it with windows and encircling it with a peristyle.

In the case of Florence Cathedral, the desired visual appearance of the pointed dome existed for many years before Brunelleschi made its construction feasible.[25] Its double-shell construction of bricks locked together in herringbone pattern (re-introduced from Byzantine architecture), and the gentle upward slope of its eight stone ribs made it possible for the construction to take place without the massive wooden formwork necessary to construct hemispherical arches. While its appearance, with the exception of the details of the lantern, is entirely Gothic, its engineering was highly innovative, and the product of a mind that had studied the huge vaults and remaining dome of Ancient Rome.[14]

Sangallo's dome looks to both these predecessors. He realised the value of both the coffering at the Pantheon and the outer stone ribs at Florence Cathedral. He simplified, strengthened and extended the peristyle of Bramante into a series of arched and ordered openings around the base, with a second such arcade set back in a tier above the first. In his hands, the rather delicate form of the lantern, based closely on that in Florence, became a massive structure, surrounded by a projecting base, a peristyle and surmounted by a spire of conic form.[26] The whole design achieves the vertical massing and complexity of a three-tiered wedding cake, complete with icing-sugar lace.

Michelangelo and Giacomo della Porta

Michelangelo redesigned the dome, taking into account all that had gone before. His dome, like that of Florence, is constructed of two shells of brick, the outer one having 16 stone ribs, twice the number at Florence but far fewer than in Sangallo's design. As with the designs of Bramante and Sangallo, the dome is raised from the piers on a drum. The encircling peristyle of Bramante and the arcade of Sangallo are reduced to 16 pairs of Corinthian columns, each of 15 metres (50 ft) high which stand proud of the building, connected by an arch. Visually they appear to buttress each of the ribs, but structurally they are probably quite redundant. The reason for this is that the dome is ovoid in shape, rising steeply as does the dome of Florence Cathedral, and therefore exerting less outward thrust than does a hemispherical dome, such as that of the Pantheon, which, although it is not buttressed, is countered by the downward thrust of heavy masonry which extends above the circling wall.[5][19]

The ovoid profile of the dome has been the subject of much speculation and scholarship over the past century. Michelangelo died in 1564, leaving the drum of the dome complete, and Bramante's piers much bulkier than originally designed, each 18 metres (59 ft) across. On his death the work continued under his assistant Vignola with Giorgio Vasari appointed by Pope Pius V as a watchdog to make sure that Michelangelo's plans were carried out exactly. Despite Vignola's knowledge of Michelangelo's intentions, little happened in this period. In 1585 the energetic Pope Sixtus appointed Giacomo della Porta who was to be assisted by Domenico Fontana. The five year reign of Sixtus was to see the building advance at a great rate.[19]

Michelangelo left a few drawings, including an early drawing of the dome, and some drawings of details. There were also detailed engravings published in 1569 by Stefan du Pérac who claimed that they were the master's final solution. Michelangelo, like Sangallo before him, also left a large wooden model. Giacomo della Porta subsequently altered this model in several ways, in keeping with changes that he made to the design. Most of these changes were of a cosmetic nature, such as the adding of lion's masks over the swags on the drum in honour of Pope Sixtus and adding a circlet of finials around the spire at the top of the lantern, as proposed by Sangallo. The major change that was made to the model, either by della Porta, or Michelangelo himself before his death, was to raise the outer dome higher above the inner one.[19]

A drawing by Michelangelo indicates that his early intentions were towards an ovoid dome, rather than a hemispherical one.[21] The engraving shows a hemispherical dome, but this was perhaps an inaccuracy of the engraver. The profile of the wooden model is more ovoid than that of the engraving, but less so than the finished product. It has been suggested that Michelangelo on his death bed reverted to the more pointed shape. However Lees-Milne cites Giacomo della Porta as taking full responsibility for the change and as indicating to Pope Sixtus that Michelangelo was lacking in the scientific understanding of which he himself was capable.[19]

Helen Gardner suggests that Michelangelo made the change to the hemispherical dome of lower profile in order to establish a balance between the dynamic vertical elements of the encircling giant order of pilasters and a more static and reposeful dome. Gardner also comments "The sculpturing of architecture [by Michelangelo]... here extends itself up from the ground through the attic stories and moves on into the drum and dome, the whole building being pulled together into a unity from base to summit."[21]

It is this sense of the building being sculptured, unified and "pulled together" by the encircling band of the deep cornice that led Mignacca to conclude that the ovoid profile, seen now in the end product, was an essential part Michelangelo's first (and last) concept. The sculptor/architect has, figuratively speaking, taken all the previous designs in hand and compressed their contours as if the building were a lump of clay. The dome must appear to thrust upwards because of the apparent pressure created by flattening the building's angles and restraining its projections.[23] If this explanation is the correct one, then the profile of the dome is not merely a structural solution, as perceived by Giacomo della Porta; it is part of the integrated design solution that is about visual tension and compression. In one sense, Michelangelo's dome may appear to look backward to the Gothic profile of Florence Cathedral and ignore the Classicism of the Renaissance, but on the other hand, perhaps more than any other building of the 1500s, it prefigures the architecture of the Baroque.

Completion

Giacomo della Porta and Fontana brought the dome to a completion in 1590, the last year of the reign of Sixtus V. His successor, Gregory XIV, saw Fontana complete the lantern and had an inscription to the honour of Sixtus V placed around its inner opening. The next pope, Clement VIII, had the cross raised into place, an event which took all day, and was accompanied by the ringing of the bells of all the city's churches. In the arms of the cross are set two lead caskets, one containing a fragment of the True Cross and a relic of St. Andrew and the other containing medallions of the Holy Lamb.[19]

In the mid-18th century, cracks appeared in the dome, so four iron chains were installed between the two shells to bind it, like the rings that keep a barrel from bursting. As many as ten chains have been installed at various times, the earliest possibly planned by Michelangelo himself as a precaution, as Brunelleschi did at Florence Cathedral.

Around the inside of the dome is written, in letters 2 metres (6.5 ft) high:

Beneath the lantern is the inscription:

Discovery of Michelangelo draft

On December 7, 2007, a fragment of a red chalk drawing of a section of the dome of Saint Peter's, almost certainly by the hand of Michelangelo was discovered in the Vatican archives.[27] The drawing shows a small precisely drafted section of the plan of the entabulature above two of the radial columns of the cupola drum. Michelangelo is known to have destroyed thousands of his drawings before his death.[28] The rare survival of this example is probably due to its fragmentary state and the fact that detailed mathematical calculations had been made over the top of the drawing. [27]

The change of plan

On the first day of Lent, February 18 1606, under Pope Paul V, the demolition of the remaining parts of the Constantinian basilica began. The marble cross set at the top of the pediment by Pope Sylvester and the Emperor Constantine was lowered to the ground. The timbers were salvaged for the roof of the Borghese Palace and two rare black marble columns, the largest of their kind, were carefully stored and later used in the narthex. The tombs of various popes were opened, treasures removed and plans made for reinterment in the new basilica.[19]

The Pope had appointed Carlo Maderno in 1602. He was a nephew of Domenico Fontana and had demonstrated himself as a dynamic architect. Maderno's idea was to ring Michelangelo's building with chapels, but the Pope was hesitant about deviating from the master's plan, even though he had been dead for forty years. The Fabbrica or building committee, a group drawn from various nationalities and generally despised by the Curia who viewed the basilica as belonging to Rome rather than Christendom, were in a quandary as to how the building should proceed. One of the matters that influenced their thinking was the Counter-Reformation which increasingly associated a Greek Cross plan with paganism and saw the Latin Cross as truly symbolic of Christianity.[19]

Another influence on the thinking of both the Fabbrica and the Curia was a certain guilt at the demolition of the ancient building. The ground on which it and its various associated chapels, vestries and sacristies had stood for so long was hallowed. The only solution was to build a nave that encompassed the whole space. In 1607 a committee of ten architects was called together, and a decision was made to extend Michelangelo's building into a nave. Maderno's plans for both the nave and the facade were accepted. The building began on May 7 1607 and proceeded at a great rate, with an army of 700 labourers being employed. The following year, the facade was begun, in December 1614 the final touches were added to the stucco decoration of the vault and early in 1615 the partition wall between the two sections was pulled down. All the rubble was carted away, and the nave was ready for use by Palm Sunday.[19]

Maderno's facade

The façade designed by Maderno, is 114.69 metres (376.28 ft) wide and 45.55 metres (149.44 ft) high and is built of travertine stone, with a giant order of Corinthian columns and a central pediment rising in front of a tall attic surmounted by statues of Christ, John the Baptist, and eleven of the apostles. The inscription on the facade reads:

| “ | IN HONOREM PRINCIPIS APOST PAVLVS V BVRGHESIVS ROMANVS PONT MAX AN MDCXII PONT VII | ” |

The façade is often cited as the least satisfactory part of the design of St. Peter's. The reasons for this, according to James Lees-Milne, are that it was not given enough consideration by the Pope and committee because of the desire to get the building completed quickly, coupled with the fact that Maderno was hesitant to deviate from the pattern set by Michelangelo at the other end of the building. Lees-Milne describes the problems of the facade as being too broad for its height, too cramped in its details and too heavy in the attic storey. The breadth is caused by modifying the plan to have towers on either side. These towers were never executed above the line of the facade because it was discovered that the ground was not sufficiently stable to bear the weight. One effect of the facade and lengthened nave is to screen the view of the dome, so that the building, from the front, has no vertical feature, except from a distance.[19]

Narthex and portals

Behind the facade of St. Peter's stretches a long portico or "narthex" such as was occasionally found in Italian Romanesque churches. This is the part of Maderno's design with which he was most satisfied. Its long barrel vault is decorated with ornate stucco and gilt, and successfully illuminated by small windows between pendentives, while the ornate marble floor is beamed with light reflected in from the piazza. At each end of the narthex is a rather theatrical space framed by ionic columns in each of which is set and equestrian figure, Charlemagne by Cornacchini (18th century) to the south and Emperor Constantine by Bernini (1670) to the north.

Five portals, of which three are framed by huge salvaged antique columns, lead into the basilica. The central portals has a bronze door created by Antonio Averulino in 1455 for the old basilica and somewhat enlarged to fit the new space.

To the single bay of Michelangelo's Greek Cross, Maderno added a further three bays. He made the dimensions slightly different to Michelangelo's bay, thus defining where the two architectural works meet. Maderno also tilted the axis of the nave slightly. This was not by accident, as suggested by his critics. An ancient Egyptian obelisk had been erected in the square outside, but had not been quite aligned with Michelangelo's building, so Maderno compensated, in order that it should, at least, align with the Basilica's facade. [19]

The nave has huge paired pilasters, in keeping with Michelangelo's work. The size of the interior is so "stupendously large" that it is hard to get a sense of scale within the building.[19][29] The four cherubs who flutter against the first piers of the nave, carrying between them two Holy Water basins, appear of quite normal cherubic size, until approached. Then it becomes apparent that each one is over 2 metres high and that real children cannot reach the basins unless they scramble up the marble draperies. The aisles each have two smaller chapels and a larger rectangular chapel, the Chapel of the Sacrament and the Choir Chapel. These are lavishly decorated with marble, stucco, gilt, sculpture and mosaic. Remarkably, there are very few paintings, although some, such as Raphael's "Sistine Madonna" have been reproduced in mosaic. The most precious painting is a small icon of the Madonna, removed from the old basilica.[19]

Maderno's last work at St. Peter's was to design a crypt-like space or "Confessio" under the dome, where the Cardinals and other privileged persons could descend in order to be nearer the burial place of the apostle. Its marble steps are remnants of the old basilica and around its balustrade are 95 bronze lamps.

Furnishing of St. Peters

Pope Urban VIII and Bernini

As a young boy Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) visited St. Peter's with the painter Annibale Carracci and stated his wish to build "a mighty throne for the apostle". His wish came true. As a young man, in 1626, he received the patronage of Pope Urban VIII and worked on the embellishment of the Basilica for 50 years. Appointed as Maderno's successor in 1629, he was to become regarded as the greatest architect and sculptor of the Baroque period. Bernini's works at St. Peter's include the baldacchino, the Chapel of the Sacrament, the plan four the niches and loggias in the piers of the dome and the chair of St. Peter.[19][21]

Baldacchino and niches

Bernini's first work at St. Peter's was to design the baldacchino, a pavilion-like structure 30 metres (98 ft) tall and claimed to be the largest piece of bronze in the world, which stands beneath the dome and above the altar. There are many baldachins in the churches of Rome, serving to create a sort of holy space above and around the table on which the Sacrament is laid for the Eucharist and emphasing the significance of this ritual. These baldachins are generally of white marble, with inlaid coloured stone. Bernini's concept was for something very different. He took his inspiration in part from eight ancient columns that had formed part of a screen in the old basilica. Their twisted barley-sugar shape had a special significance as the column to which Jesus was bound before his crucifixion was believed to be of that shape. Based on these columns, Bernini created four huge columns of bronze, twisted and decorated with olive leaves and bees, which were the emblem of Pope Urban. The baldacchino is surmounted not with an architectural pediment, like most baldacchino, but with curved Baroque brackets supporting a draped canopy, like the brocade canopies carried in processions above precious iconic images. In this case, the draped canopy is of bronze, and all the details, including the olive leaves, bees, and the portrait heads of Urban's niece in childbirth and her newborn son, are picked out in gold leaf. The baldacchino stands as a vast free-standing sculptural object, central to and framed by the largest space within the building. It is so large that the visual effect is to create a link between the enormous dome which appears to float above it, and the congregation at floor level of the basilica. It is penetrated visually from every direction, and is visually linked to the Cattedra Petri in the apse behind it and to the four piers containing large statues that are at each diagonal.[19][21]

As part of the scheme for the central space of the church, Bernini had the huge piers, begun by Bramante and completed by Michelangelo, hollowed out into niches, and had staircases made inside them, leading to four balconies. There was much dismay from those who thought that the dome might fall, but it did not. On the balconies Bernini created showcases, framed by the eight ancient twisted columns, to display the four most precious relics of the basilica, the spear of Longinus, said to have pierced the side of Christ, the veil of Veronica, with the miraculous image of the face of Christ, a fragment of the True Cross discovered in Jerusalem by Constantine's mother, Helena, and a relic of St. Andrew, the brother of St. Peter. In each of the niches that surround the central space of the basilica was placed a huge statue of the saint associated with the relic above. Only St. Longinus is the work of Bernini.[19] (See below)

Cattedra Petri and Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament

Bernini then turned his attention to another precious relic, the so-called Cathedra Petri or "throne of St. Peter" a chair which was often claimed to have been used by the apostle, but appears to date from the 12th century. As the chair itself was fast deteriorating and was no longer serviceable, Pope Alexander VII determined to enshrine it in suitable splendour as the object upon which the line of successors to Peter was based. Bernini created a large bronze throne in which it was housed, raised high on four looping supports held effortlessly by massive bronze statues of four Doctors of the Church, Saints Ambrose and Augustine representing the Latin Church and Athanasius and John Chrysostum the Greek Church. The four figures are dynamic with sweeping robes and expressions of adoration and ecstasy. Behind and above the Cattedra, a blaze of light comes in through a window of yellow alabaster, illuminating, at its centre, the Dove of the Holy Spirit. The elderly painter, Andrea Sacchi, had urged Bernini to make the figures large, so that they would be seen well from the central portal of the nave. The chair was enshrined in its new home with great celebration of January 16, 1666.[19][21]

Bernini's final work for St. Peter's, undertaken in 1676, was the decoration of the Chapel of the Sacrament. To hold the sacramental Host, he designed a miniature version in gilt bronze of Bramante's Tempietto, the little chapel that marks the place of the death of St. Peter. On either side is an angel, one gazing in rapt adoration and the other looking towards the viewer in welcome. Bernini died in 1680 in his 82nd year.[19]

St. Peter's Piazza

To the east of the basilica is the Piazza di San Pietro, (St. Peter's Square). The present arrangement, constructed between 1656 and 1667, is the Baroque inspiration of Bernini who inherited a location already occupied by an Egyptian obelisk of the 13th century BC, which was centrally placed, (with some contrivance) to Maderno's facade. The obelisk, at 25.5 metre (83.6 ft) and a total height, including base and the cross on top, of 40 metres (131 ft), is the second largest standing obelisk, and the only one to remain standing since its removal from Egypt and re-erection at the Circus of Nero, where it had stood since AD 37. Its removal to its present location by order of Pope Sixtus V and engineered by Domenico Fontana on September 28 1586, was an operation fraught with difficulties and nearly ending in disaster when the ropes holding the obelisk began to smoke from the friction. Fortunately this problem was noticed by a sailor, and for his swift intervention, his village was granted the privilege of providing the palms that are used at the basilica each Palm Sunday.[19]

The other object in the old square with which Bernini had to contend was a large fountain designed by Maderno in 1613 and set to one side of the obelisk, making a line parallel with the facade. Bernini's plan uses this horizontal axis as a major feature of his unique, spatially dynamic and highly symbolic design. The most obvious solutions were either a rectangular piazza of vast proportions so that the obelisk stood centrally and the fountain (and a matching companion) could be included, or a trapezoid piazza which fanned out from the facade of the basilica like that in front of the Palazzo Publicco in Siena. The problems of the square plan are that the necessary width to include the fountain would entail the demolition of numerous buildings, including some of the Vatican, and would minimise the effect of the facade. The trapezoid plan, on the other hand, would maximise the apparent width of the facade, which was already perceived as a fault of the design.[21]

Bernini's ingenious solution was to create a piazza in two sections. That part which is nearest the basilica is trapezoid, but rather than fanning out from the facade, it narrows. This gives the effect of countering the visual perspective. It means that from the second part of the piazza, the building looks nearer than it is, the breadth of the facade is minimised and its height appears greater in proportion to its width. The second section of the piazza is a huge elliptical circus which gently slopes downwards to the obelisk at its centre. The two distinct areas are framed by a colonnade formed by doubled pairs of columns supporting an entabulature of the simple Tuscan Order.

The part of the colonnade that is around the ellipse does not entirely encircle it, but reaches out in two arcs, symbolic of the arms of "the Roman Catholic Church reaching out to welcome its communicants".[21] The obelisk and Maderno's fountain mark the widest axis of the elipse. Bernini balanced the scheme with another fountain in 1675. The approach to the square used to be through a jumble of old buildings, which added an element of surprise to the vista that opened up upon passing through the colonnade. Nowadays a long wide street, the Via della Conciliazione, built by Mussolini after the conclusion of the Lateran Treaties, leads from the River Tiber to the piazza and gives distant views of St. Peter's as the visitor approaches.[19]

Bernini's transformation of the site is entirely Baroque in concept. Where Bramante and Michelangelo conceived a building that stood in "self-sufficient isolation", Bernini made the whole complex "expansively relate to its environment".[21] Banister Fletcher says "No other city has afforded such a wide-swept approach to its cathedral church, no other architect could have conceived a design of greater nobility...(it is) the greatest of all atriums before the greatest of all churches of Christendom."[5]

Treasures

Tombs and relics

There are over 100 tombs within St. Peter's Basilica, many located in the Vatican grotto, beneath the Basilica. These include 91 popes, St. Ignatius of Antioch, Holy Roman Emperor Otto II, and the composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. Exiled Catholic British royalty James Francis Edward Stuart and his two sons, Charles Edward Stuart and Henry Benedict Stuart, are buried here, having been granted asylum by Pope Clement XI. Also buried here are Maria Clementina Sobieska, wife of Charles Edward Stuart, and Queen Christina of Sweden, who abdicated her throne in order to convert to Catholicism. The most recent interment was Pope John Paul II, on April 8 2005. Beneath, near the crypt, is the recently-discovered vaulted fourth-century "Tomb of the Julii". (See below for some descriptions of tombs)

Artworks

The towers and narthex

In the towers to either side of the facade are two clocks. The clock on the left has been operated electrically since 1931. Its oldest bell dates from 1288. One of the most important treasures of the cathedral is a mosaic set above the central external door. Called the "Navicella", it is based on a design by Giotto (early 13th century) and represents a ship symbolising the Christian Church. At each end of the narthex is an equestrian figure, to the north Emperor Constantine by Bernini (1670) and to the south Charlemagne by Cornacchini (18th century). Of the five portals, three contain notable doors. The central portal has the Renaissance bronze door by Antonio Averulino (1455), enlarged to fit the new space. The southern door, the "Door of the Dead", was designed by 20th century sculptor Giacomo Manzù and includes a portrait of Pope John XXIII kneeling before the crucified figure of St. Peter.

The northernmost door is the "Holy Door" which, by tradition, is opened only for holy years such as the Jubilee year. The present door is bronze and was designed by Vico Consorti in 1950. Above it are inscriptions commemorating the opening of the door: PAVLVS V PONT MAX ANNO XIII and GREGORIVS XIII PONT MAX. Recent commemorative plaques read:

|

IOANNES PAVLVS II P.M. |

IOANNES PAVLVS II P.M. |

PAVLVS VI PONT MAX |

| In the jubilee year of human redemption 1983-4, John Paul II, Pontifex Maximus, opened and closed again the holy door closed and set apart by Paul VI in 1976. | John Paul II, Pontifex Maximus, again opened and closed the holy door in the year of the great jubilee, from the incarnation of the Lord 2000-2001. | Paul VI, Pontifex Maximus, opened and closed the holy door of this patriarchal Vatican basilica in the jubilee year of 1975. |

- On the first piers of the nave are two Holy Water basins held by pairs of cherubs each 2 metres high, commissioned by Pope Benedict XIII from designer Agostino Cornacchini and sculptor Francesco Moderati, (1720s).

- Along the floor of the nave are markers showing the comparative lengths of other churches, starting from the entrance.

- On the decorative pilasters of the piers of the nave are medallions with relief depicting the first 38 popes.

- In niches between the pilasters of the nave are statues depicting 39 founders of religious orders.

- Set against the north east pier of the dome is a statue of St. Peter Enthroned, sometimes attributed to late 13th century sculptor Arnolfo di Cambio, with some scholars dating it to the 5th century. One foot of the statue is largely worn away due to centuries of pilgrims kissing it.

- The sunken Confessio leading to the Vatican Grottoes (see above) contains a large kneeling statue by Canova of Pope Pius VI, who was captured and mistreated by the Napoleon's army.

- The High Altar is surmounted by Bernini's baldachin. (See above)

- Set in niches within the four piers supporting the dome are the statues associated with the basilica's holy relics: St. Helena holding the True Cross, by Andrea Bolgi); St. Longinus holding the spear that pierced the side of Jesus, by Bernini (1639); St. Andrew with the St. Andrew's Cross, by Francois Duquesnoy and St. Veronica holding her veil with the image of Jesus' face, by Francesco Mochi.

North aisle

- In the first chapel of the north aisle is Michelangelo's Pietà.[30]

- On the first pier in the right aisle is the monument of Queen Christina of Sweden, who abdicated in 1654 in order to convert to Catholicism.

- The second chapel, dedicated to St. Sebastian, contains the tombs of popes Pius XI and Pius XII.

- The large chapel on the right aisle is the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament which contains the tabernacle by Bernini (1664) resembling Bramante's Tempietto at San Pietro in Montorio supported by two kneeling angels and with behind it a painting of the Holy Trinity by Pietro da Cortona.

- Near the altar of Our Lady of Succour are the monuments of popes Gregory XIII by Camillo Rusconi (1723) and Gregory XIV.

- At the end of the aisle is an altar containing the relics of St. Petronilla and with an altarpiece "The Burial of St Petronilla by Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri), 1623.

South aisle

- The first chapel in the south aisle is the baptistry, commissioned by Pope Innocent XII and designed by Carlo Fontana, (great nephew of Domenico Fontana). The font, which was previously located in the opposite chapel, is the red porphyry sarcophagus of Probus, the 4th century Prefect of Rome. The lid came from a different sarcophagus, which had once held the remains of the Emperor Hadrian and in removing it from the Vatican Grotto where it had been stored, the workmen broke it into ten pieces. Fontana restored it expertly and surmounted it with a gilt-bronze figure of the "Lamb of God".

- Against the first pier of the aisle is the Monument to the Royal Stuarts, James and his sons, Charles Edward, known as "Bonnie Prince Charlie" and Henry, Cardinal and Duke of York. The tomb is a Neo-Classical design by Canova unveiled in 1819. Opposite it is the memorial of Charles Edward Stuart's wife, Maria Clementina Sobieska.

- The second chapel is that of the Presentation of the Virgin' and contains the tombs of Pope Benedict XV and Pope John XXIII.

- Against the piers are the tombs of Pope Pius X and Pope Innocennt VIII.

- The large chapel off the south aisle is the Choir Chapel which contains the altar of the Imacculate Virgin Mary.

- At the entrance to the Sacristy is the tomb of Pope Pius VIII

- The south transept contains the altars of St. Thomas, St. Joseph and the Crucifixion of St. Peter.

- The tomb of Fabio Chigi, Pope Alexander VII, towards the end of the aisle, is the work of Bernini and called by Lees-Milne "one of the greatest tombs of the Baroque Age". It occupies an awkward position, being set in a niche above a doorway into a small vestry, but Bernini has utilised the doorway in a symbolic manner. Pope Alexander kneels upon his tomb, facing outward. The tomb is supported on a large draped shroud patterned red marble, and is supported by four female figures, of whom only the two at the front are fully visible. They represent Charity and Truth. The foot of Truth rests upon a globe of the world, her toe being pierced symbolically by the thorn of Protestant England. Coming forth, seemingly, from the doorway as if it was the entrance to a tomb, is the skeletal winged figure of Death, its head hidden beneath the shroud, but its right hand carrying an hour-glass stretched upward towards the kneeling figure of the pope. [19]

Archpriests of Saint Peter’s Basilica since 1125

List of archpriests of the Vatican Basilica[31]

|

|

Notes

- ↑ James Lees-Milne, St Peter's, p. 13, describes St Peter's Basilica as "a church with a unique position in the Christian world.

- ↑ Banister Fletcher, the renowned architectural historian calls it "...The greatest of all churches of Christendom". p.719

- ↑ "The greatest church in Christendom",Roma 2000

- ↑ Columbia Magazine, April 2006, page 18.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Banister Fletcher, The History of Architecture on the Comparative Method

- ↑ Helen Dietz, The Eschatological Dimension of Church Architecture (2005)

- ↑ Claims made that the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro in Africa is larger appear to be spurious, as the measurements include a rectorate, a villa and probably the forecourt. Its capacity is 18,000 people against St. Peter's 60,000. Its dome, based on that of St. Peter's, is lower but carries a taller cross, and thus claims to be the tallest domed church.

- ↑ Columbia Magazine, April 2006, page 18.

- ↑ St. Peter's Basilica, monuments

- ↑ "University of Alberta Express News". In search of St. Peter's Tomb. Retrieved on 2006-12-25.

- ↑ Boorsch, Suzanne (Winter 1982-1983). "The Building of the Vatican: The Papacy and Architecture". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 40 (3): 4–8.

- ↑ James Lees-Milne, Saint Peter's

- ↑ Quarrying of stone for the Colosseum had, in turn, been paid for with treasure looted at the Fall of Jerusalem and destruction of the temple by the emperor Vespasian's general (and the future emperor) Titus in 70 AD.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Frederick Hartt, A History of Italian Renaissance Art'

- ↑ Bramante's plan, Helen Gardner p.458

- ↑ Raphael's plan, Banister Fletcher p.722

- ↑ Peruzzi's plan, Banister Fletcher p.722

- ↑ Sangallo's plan, Banister Fletcher p.772

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 19.12 19.13 19.14 19.15 19.16 19.17 19.18 19.19 19.20 19.21 <James Lees-Milne, Saint Peter's

- ↑ Ludwig Goldscheider, Michelangelo

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 21.8 Helen Gardner, Art through the Ages

- ↑ Michelangelo's plan, Helen Gardner p.478

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Eneide Mignacca, Michelangelo and the architecture of St. Peter's Basilica, lecture, Sydney University, (1982)

- ↑ This claim has recently been made for Yamoussoukro Basilica, the dome of which, modelled on St. Peter's, is lower but has a taller cross

- ↑ The dome of Florence Cathedral is depicted in a fresco at Santa Maria Novella that pre-dates its building by about 100 years.

- ↑ Sangallo's plan, Banister Fletcher p.722

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Michelangelo 'last sketch' found". BBC News (2007-12-07). Retrieved on 2007-12-08.

- ↑ BBC, Rare Michelangelo sketch for sale, Friday, 14 October 2005, [1] accessed: 2008-02=09

- ↑ The word "stupendous" is used by a number of writers trying to adequately describe the enormity of the interior. These include James Lees-Milne and Banister Fletcher.

- ↑ The statue was damaged in 1972 by Lazlo Toft, a Hungarian-Australian, who considered that the veneration shown to the statue was idolatrous. The damage was repaired and the statue subsequently placed behind glass.

- ↑ Source: the respective biographical entries on Essay of a General List of Cardinals by Salvador Miranda with corrections provided by Werner Maleczek, Papst und Kardinalskolleg von 1191 bis 1216, Wien 1984 for the period before 1190 until 1254

References

- Bannister, Turpin. “The Constantian Basilica of Saint Peter at Rome.” The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (March 1968) 3-32.

- Boorsch, Suzanne. “The Building of the Vatican: The Papacy and Architecture.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (Winter 1982) 1-2;4-64.

- Hintzen-Bohlen, Brigitte and Sorges, Jurgen. Rome and the Vatican City, Konemann, ISBN 3829031092

- Finch, Margaret. "The Cantharus and Pigna at Old Saint Peter’s," Gesta Vol 30 #1 (1991).

- Fletcher, Banister. A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method, first published 1896, current edition 2001, Elsevier Science & Technology ISBN 0750622679

- Frommel, Christoph. “Papal Policy: The Planning of Rome during the Renaissance.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History. (Summer 1986) 39-65.

- Hartt, Frederick. A History of Italian Renaissance Art. Thames and Hudson (1970) ISBN 0500231362

- McClendon, Charles. The History of the Site of St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome. Perspecta. (1989) 32-65.

- Lees-Milne, James. Saint Peter's, Hamish Hamilton (1967). ISBN

- Gardner, Helen. Art through the Ages, 5th edition, Harcourt, Brace and World, inc., ISBN 07679933

- Goldscheider, Ludwig. Michelangelo, 1964, Phaidon, ISBN 100714832960

- Kleiner, Fred and Christin Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective. v2. 12th edition. (Thomas Wadsworth, 2006), 499-500, 571-575.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus An Outline of European Architecture, Pelican, 1964, ISBN 9780140201093

- Pinto, Pio V. The Pilgrim's Guide to Rome, Harper and Row, (1974), ISBN 0600133880

- Scotti, R.A. BASILICA The Splendor and the Scandal: The Building of St. Peter's , Viking and Row, (2006), ISBN 0670037761

- UNESCO website on the Holy See.

- Lees-Milne, James. St. Peter's Little Brown and Co. (1967)

- Inside the Vatican, a National Geographic Television Special

External links

- stpetersbasilica.org Largest online site for the Basilica

- Fullscreen Virtual Tour by Virtualsweden

- Google Maps Satellite image of the Basilica

- St Peter’s Basilica and St Peter’s Tomb

- Circus of Nero and the old and new Basilicas superimposed, showing the tomb of Peter

- St. Peter's Basilica Photo Gallery 249 photos

- St Peter's Basilica, Rome pictures and virtual reality movies

- Basilica of St Peter, Rome by Activitaly

- Catholic Encyclopedia Catholic Encyclopedia article

- Vatican City, Piazza San Pietro VR panorama with map and compass effect by Tolomeus

- The pipe organs of St Peter's Basilica

- Vatican City, Piazza San Pietro QTVR panorama hi-res (15 Mb) by Tolomeus

- St. Peter's Basilica Floor Plan

- The Bells of St. Peter's Basilica at Vatican

|

|||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||