Barn Owl

- The city in Russia is spelled Barnaul.

| Barn Owl | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

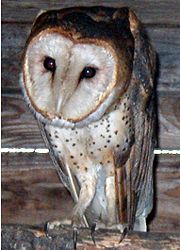

Light adult, representative of T. a. alba or T. a. delicatula

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Conservation status | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tyto alba (Scopoli, 1769) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

Global range in green

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Synonyms | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lechusa stirtoni Miller, 1956 |

The Barn Owl (Tyto alba) is the most widely distributed species of owl, and one of the most widespread of all birds. It is also referred to as Common Barn Owl, to distinguish it from other species in the barn-owl family Tytonidae. These form one of the two living main lineages groups of owls, the other being the typical owls (Strigidae). T. alba is found almost anywhere in the world outside polar and desert regions, as well as all of Asia north of the Alpide belt, New Zealand, and most of Indonesia and the Pacific islands.[1]

It is known by many other vernacular names, some of them rather ambiguous. They often refer to the appearance, habitat or the eerie, silent flight: White Owl, Silver Owl, Demon Owl, Ghost Owl, Death Owl, Night Owl, Rat Owl, Monkey-faced Owl, Church Owl, Cave Owl or Stone Owl. Golden Owl might also refer to the related Golden Masked-owl (T. aurantia). Hissing Owl and – particularly in the USA – "screech owl" refer to the piercing calls of these birds, but the latter term usually refers to typical owls of the genus Megascops.

The Ashy-faced Owl (T. glaucops) was for some time included in T. alba, and by some authors its Lesser Antilles populations insularis and nigrescens still are. The Barn Owls from the Indopacific region are sometimes separated as Eastern Barn-owl, Australian Barn-owl or Delicate Barn-owl (T. delicatula). While this may be warranted, it is not clear between which races to draw the line between the two species. Also, some island subspecies are occasionally treated as distinct species. While all this may be warranted, such a move is generally eschewed pending further information on Barn Owl phylogeography.[1]

Contents |

Description

The Barn Owl is a pale, long-winged, long-legged owl with a short squarish tail. Depending on subspecies, it measures c.25-45 cm in overall length, with a wingspan of about 75-100 cm. Tail shape is a way of distinguishing the Barn Owl from true owls when seen in flight, as are the wavering motions and the dangling feathered legs. The light face with its peculiar shape and the black eyes give the flying bird an odd and startling appearance, like a flat mask with oversized oblique black eyeslits, the ridge of feathers above the bill somewhat resembling a nose.[2]

Its head and upperparts are a mixture of buff and grey (especially on the forehead and back) feathers in most subspecies. Some are purer richer brown instead, and all have fine black-and-white speckles except on the remiges and rectrices, which are light brown with darker bands. The heart-shaped face is usually bright white, but in some subspecies it is browner. The underparts (including the tarsometatarsus feathers) vary from white to reddish buff among the subspecies, and are either mostly unpatterned or bear a varying amount of tiny blackish-brown speckles. The bill varies from pale horn to dark buff, corresponding to the general plumage hue. The iris is blackish brown. The toes, as the bill, vary in color; their color ranges from pinkish to dark pinkish-grey. The talons are black.[1]

Contrary to popular belief, it does not hoot (such calls are made by typical owls, like the Tawny Owl or other Strix). It instead produces the characteristic shree scream, ear-shattering at close range. It can hiss like a snake, and when captured or cornered, it throws itself on its back and flails with sharp-taloned feet, making for an effective defence.[2]

Subspecies

Across its vast range, the Barn Owl has formed many subspecies, but several are considered to be intergrades between more distinct populations today. Still, some 20-30 seem to be worthy of recognition as long as the species is not split up. They vary mainly in size and color, sometimes according to Bergmann's and Gloger's Rules, sometimes more unpredictably. This species ranges in color from the almost beige-and-white nominate subspecies, erlangeri and niveicauda to the nearly black-and-brown contempta:[1]

- Tyto alba alba (Scopoli, 1769) – W Europe from the British Isles south to the Maghreb and west along Mediterranean coastal regions to NW Turkey in the north and the Nile in the south, where it reaches upstream to NE Sudan. Also Aïr Mountains in the Sahara of Niger, Balearic Islands and Sicily in the Mediterranean, andthe W Canary Islands (El Hierro, La Gomera, La Palma Gran Canaria and Tenerife). Intergrades with guttata along the Rhine and lower Meuse rivers, and with affinis around the Egypt-Sudan border. Includes hostilis, kirchhoffi, kleinschmidti, pusillus. African populations might belong to erlangeri.

- Upperparts grey and light buff. Underparts white, with little if any black spots.

- Tyto alba javanica (J.F.Gmelin, 1788) – Malay Peninsula through the southern Greater Sunda Islands including Kangean Islands, Krakatoa and the Thousand Islands; also Alor Archipelago, Kalao and Tanahjampea in the Selayar Islands, Kalaotoa, and possibly S Borneo. Southeast Asian birds are sometimes placed here but seem closer to stertens.

- Large. Similar to alba but darker above, and with conspicuous speckling overall.

- Tyto alba furcata (Temminck, 1827) – Cuba, Jamaica, Cayman Islands. Might include niveicauda.

- Large. Upperparts pale orange-buff and brownish-grey, underparts whitish with few speckles. Face white.

- Tyto alba tuidara (J.E.Grey, 1829) – South American lowlands east of the Andes and south of the Amazon River all the way south to Tierra del Fuego; also on the Falkland Islands. Includes hauchecornei and possibly hellmayri.

- Upperparts grey and orange-buff. Underparts whitish to light buff with little speckling. Face white. Resembles pale Old World guttata.

- Tyto alba guttata (C.L.Brehm, 1831) – C Europe north of the Alps from the Rhine to Latvia, Lithuania and Ukraine, and south to Romania, NE Greece and the S Balkans. Intergrades with alba at the western border of its range. Includes rhenana.

- More grey on upperparts than alba. Underparts buff to rufous with some dark speckles. Face whitish. Females are on average redder below than males.

- Tyto alba delicatula (Gould, 1837) – Australia and offshore islets (not on Tasmania), Lesser Sunda Islands (Savu, Timor, Jaco, Wetar, Kisar, Tanimbar, possibly Rote), Melanesia (New Caledonia and Loyalty Islands; Aneityum, Erromango and Tanna in S Vanuatu; Solomon Islands including Bougainville; Long Island, Nissan, Buka and perhaps New Ireland and N New Britain), W Polynesia (Fiji and Rotuma, Niue, Samoan Islands, Tonga, Wallis and Futuna); introduced to Lord Howe Island but became extinct again. Includes bellonae, everetti, kuehni, lifuensis and lulu. Reports of blackish barn-owls on Fiji require investigation.

- Similar to alba; slightly darker above, more speckles below. Tail with 4 bark brown bars.

- Tyto alba pratincola (Bonaparte, 1838) – N Americas from S Canada south to C Mexico; Bermuda, Bahamas, Hispaniola; introduced to Lord Howe Island where it became extinct again and to Hawaiʻi (where it persists). Includes lucayana and might include bondi, guatemalae, subandeana.

- Large. Upperparts grey and orange-buff. Underparts whitish to light buff with much speckling. Face white. Resembles pale Old World guttata, but usually more speckles below.

- Tyto alba punctatissima (G.R.Grey, 1838), Galápagos Barn-owl – Endemic to the Galápagos islands. Sometimes considered a distinct species.

- Small. Dark greyish brown above, with white part of spots prominent. Underparts white to golden buff, with distinct pattern of brown vermiculations or fine dense spots.

- Tyto alba poensis (Fraser, 1842) – Endemic to Bioko, if not the same as affinis.

- Upperparts golden-brown and grey with very bold pattern. Underparts light buff with extensive speckles. Face white.

- Tyto alba thomensis (Hartlaub, 1852) – Endemic to São Tomé Island. A record from Príncipe is in error. Sometimes considered a distinct species.

- Smallish. Upperparts dark brownish grey with bold pattern, including lighter brown bands on remiges and rectrices. Underparts golden brown with extensive speckles. Face buff.

- Tyto alba affinis (Blyth, 1862) – Sub-Saharan Africa, including the Comoros, Madagascar, Pemba and Unguja islands; introduced to the Seychelles. Intergrades with alba around the Egypt-Sudan border. Includes hypermetra; doubtfully distinct from poensis.

- Upperparts very grey. Underparts light buff with extensive speckles. Face white.

- Tyto alba guatemalae (Ridgway, 1874) – Guatemala or S Mexico through Central America to Panama or N Colombia; Pearl Islands. Includes subandeana; doubtfully distinct from pratincola.

- Similar to dark pratincola; less grey above, coarser speckles below.

- Tyto alba deroepstorffi (Hume, 1875) – Endemic to the S Andaman Islands. Sometimes considered a distinct species.

- Smallish. Almost uniformly dark reddish brown above. Reddish buff below, with some speckling. Face reddish buff.

- Tyto alba bargei (Hartert, 1892) – Endemic to Curacao and maybe Bonaire in the West Indies.

- Similar to alba; smaller and noticeably short-winged.

- Tyto alba sumbaensis (Hartert, 1897) – Endemic to Sumba.

- Large, particularly the bill. Similar to javanica; tail whitish with black bars.

- Tyto alba contempta (Hartert, 1898) – NE Andes from W Venezuela through E Colombia (may be absent from Cordillera Central and Cordillera Occidental) south to Peru. Includes stictica.

- Almost black with some dark grey above, the white part of the spotting showing prominently. Reddish brown below

- Small. Similar to guttata, but breast region light buff.

- Similar to alba; breast region always pure unspotted white.

- Tyto alba gracilirostris (Hartert, 1905), Canary Barn-owl – Endemic to the E Canary Islands (Chinijo Archipelago, Fuerteventura, Lanzarote; perhaps formerly also on Lobos).

- Small. Similar to schmitzi but breast darker, approaching guttata. Face light buff.

- Tyto alba meeki (Rothschild & Hartert, 1907) – E New Guinea and Manam and Karkar islands.

- Large. Similar to javanica; tail whitish with grey bars, underparts silvery-white with arrowhead-shaped speckles (larger than in javanica).

- Tyto alba detorta Hartert, 1913 – Endemic to the Cape Verde Islands. Sometimes considered a distinct species.

- Similar to guttata, but less reddish. Face buff.

- Tyto alba erlangeri W.L.Sclater, 1921 – Crete and southern Aegean islands to Cyprus; Near and Middle East including Arabian Peninsula coastlands, south to Sinai and east to SW Iran. Might include African populations assigned to alba.

- Similar to ernesti; upperparts lighter and yellower.

- Tyto alba stertens Hartert, 1929 – W Pakistan through India east to Yunnan and Vietnam, south S Thailand; N Sri Lanka. Southeast Asian birds sometimes included in javanica.

- Similar to alba, but noticeably speckled below.

- Tyto alba crassirostris Mayr, 1935 – Endemic to the Tanga Islands

- Similar to delicatula; darker, with stronger bill and feet.

- Tyto alba interposita Mayr, 1935 – Santa Cruz and Banks Islands south to Efate (Vanuatu).

- Similar to delicatula; darker, with orange hue.

- Tyto alba hellmayri Griscom & Greenway, 1937 – NE South American lowlands from E Venezuela south to the Amazon River. Doubtfully distinct from tuidara.

- Similar to tuidara but larger.

- Tyto alba bondi Parks & Phillips, 1978 – Endemic to Roatán and Guanaja in the Bay Islands. Doubtfully distinct from pratincola.

- Similar to pratincola; smaller and paler on average.

- Tyto alba niveicauda Parks & Phillips, 1978 – Endemic to Isla de la Juventud. Doubtfully distinct from furcata.

- Large. Similar to furcata; paler in general. Resembles Old World alba.

Ecology and status

This is a bird of open country such as farmland or grassland with some interspersed woodland, usually below 2,000 m ASL but occasionally as high as 3,000 m ASL in the Tropics[3]. This owl prefers to hunt along the edges of woods. It has an effortless wavering flight as it quarters pastures or similar hunting grounds. Like most owls, the Barn Owl flies silently; tiny serrations on the leading edges of its flight feathers help to break up the flow of air over its wings, thereby reducing turbulence and the noise that accompanies it[4].

It hunts by flying low and slowly over an area of open ground, hovering over spots that conceal potential prey. The Barn Owl feeds primarily on small vertebrates, particularly rodents. Studies have shown that an individual Barn Owl may eat one or more rodents per night; a nesting pair and their young can eat more than 1,000 rodents per year[5]. Locally superabundant rodent species in the weight class of several grams per individual usually make up the single largest proportion of prey, no matter whether they are Muridae[6] or Cricetidae[7]. Such animals probably make up at least three-quarters of the biomass eaten by each and every T. alba.[8]

The diet is supplemented with local small vertebrate and large invertebrate life. A Barn Owl will eat anything it can subdue and that is more than a beakful, from small invertebrates weighing less than 0.05 grams to birds weighing as much as the owl itself, like the Spotted Nothura (Nothura maculosa). Contrary to what is sometimes assumed, the Barn Owl does not eat domestic animals on any sort of regular basis; it might snatch a young chicken or guinea pig once or twice in its life, but that is all. Regionally, different foods outside of rodents are utilized as per availability. On bird-rich islands, a Barn Owl might contain some 15-20% birds in its diet, while in grassland it will gorge itself on Orthoptera such as Copiphorinae katydids, Jerusalem crickets (Stenopelmatidae) or true crickets (Gryllidae). Bats and even toads and squamates may as well make up a minor but conspicuous part of the prey.[8]

The Barn Owl has acute hearing, with ears placed asymmetrically for improved detection of sound position and distance, and it does not require sight to hunt. Hunting nocturnally or crepuscularly, it can target and dive down, penetrating it talons through snow, grass or brush to seize rodents with deadly accuracy. Compared to other owls of similar size, the Barn Owl has a much higher metabolic rate, requiring relatively more food. Pound for pound, Barn Owls consume more rodents – often regarded as pests by humans – than possibly any other creature. This makes the Barn Owl one of the most economically valuable wildlife animals to farmers. Farmers often find these owls more effective than poison in keeping down rodent pests, and they can encourage Barn Owl habitation by providing nest sites.[9]

The Barn Owl builds a nest of sorts, but unlike in typical owls it is just a scrape in any unsorted debris as has assembled in a hollow with narrow entrance. Typical nest sites include tree stumps and cliff crevices, but these owls will readily nest in attics, vacant and ruined buildings, and even wells, chimneys, hunting blinds and similar locations. The usual clutch consists of roughly half a dozen eggs, but may be as small as 2; very large clutches of more than a dozen eggs might be of 2-3 females.[1]

Predators of the Barn Owl include large American opossums (Didelphis), the Common Raccoon (Procyon lotor), and similar carnivorous mammals, as well as large raptors such as hawks, eagles, and other owls. Among the latter, the Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus) and the Eurasian Eagle-owl (B. bubo) are noted predators of Barn Owls. Some fall also victim to large snakes, but the biggest threat are humans and their pets, in particular house or feral cats.

Barn Owls are relatively common throughout most of their range. However, locally severe declines from organochlorine (e.g. DDT) poisoning in the mid-20th century and rodenticides in the late 20th century have affected some populations[1]. While the Barn Owl is prolific and will often make good any population decrease soon enough, they are rare in Britain today. The most recent survey their population in the UK at around 4,400 breeding pairs. In the USA, Barn Owls are listed as endangered species in seven Midwestern states.

Common names like "Demon Owl", "Death Owl" or "Ghost Owl" show that for long, the rural population considered Barn Owls to be birds of evil omen in many places. Consequently, they were often persecuted by farmers, unawares of the benefit these birds bring. As late as 1975, hunting by fearful locals was limiting the population of T. a. gracilirostris on Fuerteventura. In our time, rodenticide poisoning is the main threat for the Canary Barn-owl, which in the Chinijo Archipelago is on the verge of disappearance while on Fuerteventura only a few dozen pairs remain overall. There, the abandonment of much agricultural land and the subsequent decline of rodent pests seem to have decreased the owl's numbers even further. Only on Lanzarote does a somewhat larger number of these birds still seem to exist, but altogether this particular subspecies is precariously rare: Probably less than 300 and perhaps less than 200 birds still exist, and it is classified as insuficientemente conocida ("data deficient") by the Spanish Ministry of Environment. Similarly, the birds on the western Canary Islands which are usually assigned to the nominate subspecies (though this seems suspect on grounds of biogeography) have declined much, and here wanton destruction seems still to be significant. On Tenerife they seem to be not uncommon, while on the other islands, the situation looks about as bleak as on Fuerteventura. Due to the assignment to the nominate subspecies, which is common in mainland Spain, the western Canary Islands population is not classified as threatened.[10]

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Bruce (1999)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Bruce (1999), Svensson et al. (1999): pp.212-213

- ↑ Cisneros-Heredia (2006)

- ↑ Ehrlich et al. (1994): pp.250-254

- ↑ Ingles (1995), PGC (2008)

- ↑ E.g. Black Rat (Rattus rattus) or House Mouse (Mus musculus): Cisneros-Heredia (2006), Motta-Junior (2006)

- ↑ E.g. Delicate Vesper Mouse (Calomys tener), Hairy-tailed Bolo Mouse (Bolomys lasiurus) or Black-footed Pygmy Rice Rat (Oligoryzomys nigripes): Motta-Junior (2006)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ehrlich et al. (1994): pp.250-254, Motta-Junior (2006)

- ↑ UF (1999), Day (2001)

- ↑ Álamo Tavío (1975), Palacios (2004), MES (2006)

References

- Álamo Tavío, Manuel (1975): Aves de Fuerteventura en peligro de extinción ["Endangered Birds of Fuerteventura"]. In: Asociación Canaria para Defensa de la Naturaleza (ed.): Aves y plantas de Fuerteventura en peligro de extinción: 10-32 [in Spanish]. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. PDF fulltext

- BirdLife International (BLI) (2004). Tyto alba. 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. Retrieved on 11 May 2006.

- Bruce, M.D. (1999): Family Tytonidae (Barn-owls). In: del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A. & Sargatal, J. (eds): Handbook of Birds of the World (Vol.5: Barn-owls to Hummingbirds): 34-75, plates 1-3. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. ISBN 84-87334-25-3

- Cisneros-Heredia, Diego F. (2006): Notes on breeding, behaviour and distribution of some birds in Ecuador. Bull. B.O.C. 126(2): 153-164. PDF fulltext

- Day, Charles (2001): Researchers uncover the neural details of how Barn Owls locate sound sources. Phys. Today 54(6): 20-22. HTML fulltext

- Ehrlich, Paul Ralph; Dobkin, David S.; Wheye, Darryl & Pimm, Stuart L. (1994): The Birdwatcher's Handbook: A Guide to the Natural History of the Birds of Britain and Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-858407-5

- Ingles, Chuck (1995): Summary of California studies analyzing the diet of barn owls. Sustainable Agriculture/Technical Reviews 7(2): 14-16. HTML fulltext

- Ministry of the Environment of Spain (MES) (2006): [Tyto alba gracilirostris status report] [in Spanish]. PDF fulltext

- Motta-Junior, José Carlos (2006): Relações tróficas entre cinco Strigiformes simpátricas na região central do Estado de São Paulo, Brasil [Comparative trophic ecology of five sympatric Strigiformes in central State of São Paulo, south-east Brazil]. Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 14(4): 359-377 [Portuguese with English abstract]. PDF fulltext

- Palacios, César-Javier (2004): Current status and distribution of birds of prey in the Canary Islands. Bird Conservation International 14(3): 203–213. doi:10.1017/S0959270904000255 PDF fulltext

- Pennsylvania Game Commission (PGC) (2008): Barn Owl Conservation Initiative. Version of 2008-AUG-25. Retrieved 2008-OCT-03.

- Svensson, Lars; Zetterström, Dan; Mullarney, Killian & Grant, Peter J. (1999): Collins Bird Guide. Harper & Collins, London. ISBN 0-00-219728-6

- University of Florida (UF) (1999): Spooky Owl Provides Natural Rodent Control For Farmers. Version of 1999-OCT-28. Retrieved 2008-OCT-03.

Further reading

- Bachynski, K. & Harris, M. (2002): Animal Diversity Web: Tyto alba (barn owl). Retrieved 2006-9-21.

- Taylor, Iain (1994): Barn Owls: Predator-Prey Relationships and Conservation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39290-X

External links

- Birdlife species factsheet

- BrainMaps: Tyto alba (barn owl) brain

- Barn Owl videos at the Internet Bird Collection website

- ARKive-Barn Owl video

- Barn Owl - Tyto alba - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Barn Owl Species Account - Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Barn Owl Information - South Dakota Birds

- BTO - BOMP - BTO Barn Owl Monitoring Project (BOMP)

- Suffolk Community Barn Owl Project - Suffolk Community Barn Owl Project

- Barn Owl Project in Austria - Barn Owl Project in Austria

- BBC - Wales - Barn Owls - BBC Wales Barn Owl page

- World Owl Trust Website

- Ageing and sexing (PDF) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta