Baphomet

Baphomet is a name of unestablished origin, but probably an Old French corruption and misspelling of the name Mahomet (Muhammad).[1] It first appeared in the mid-thirteenth century in clear reference to Muhammad, but later appeared as a term for a pagan idol in trial transcripts of the Inquisition of the Knights Templar in the early 1300s.

However, in the 19th century the name came into popular English-speaking consciousness with the publication of various pseudo-history works that tried to link the Knights Templar with conspiracy theories elaborating on their suppression. The name Baphomet then became associated with a "Sabbatic Goat" image drawn by Eliphas Lévi.

Contents |

History

The name Baphomet traces back to the end of the Crusades. Around 1250, in an Occitan poem bewailing the defeat of the Seventh Crusade, Austorc d'Aorlhac refers to "Bafomet".

When the medieval order of the Knights Templar was suppressed by King Philip IV of France, on Friday, October 13, 1307, King Philip had many French Templars simultaneously arrested, and then tortured into confessions. The name Baphomet comes up in several of these confessions, in reference to an idol of some type that the Templars were said to have been worshipping. The description of the object changed from confession to confession. Some Templars denied any knowledge of it. Others, under torture, described it as being either a severed head, a cat, or a head with three faces.[2]

The charge was notable because it was different from usual forced confessions. Over 100 different charges had been leveled against the Templars, most of them clearly false, as they were the same charges that were leveled against many of King Philip's enemies. For example, he had earlier kidnapped Pope Boniface VIII and charged him with near identical offenses of heresy, spitting and urinating on the cross, and sodomy. However, the charges about the worship of an idol named Baphomet, were unique to the Inquisition of the Templars.[3][4] As Karen Ralls has pointed out, "There is no mention of Baphomet either in the Templar Rule or in other medieval period Templar documents".[5]

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the name's first appearance in English was in Henry Hallam's 1818 work Middle Ages, reproducing an early French corruption of "Mahomet", a common variant of Arabic محمد Muhammad.[6] The name Baphomet also appeared in the English translation of the Viennese Orientalist Joseph Freiherr von Hammer-Purgstall's Mysterium Baphometis revelatum as The Mystery of Baphomet Revealed,[7] which presented an elaborate pseudohistory constructed to discredit the Freemasons by linking them with "Templar masons". He argued, using archaeological evidence faked by earlier scholars and literary evidence such as the Grail romances, that the Templars were Gnostics and the 'Templars' head' was a Gnostic idol called Baphomet.

Some modern scholars such as Peter Partner and Malcolm Barber agree that the name of Baphomet was an Old French corruption of the name Muhammad, with the interpretation being that some of the Templars, through their long military occupation of the Outremer, had begun incorporating Islamic ideas into their belief system, and that this was seen and documented by the Inquisitors as heresy.[1] Peter Partner's 1987 book The Knights Templar and their Myth says, "In the trial of the Templars one of their main charges was their supposed worship of a heathen idol-head known as a 'Baphomet' ('Baphomet' = Mahomet = Muhammad)." Partner's book also provides a quote from a poem written in a Provencal dialect by a troubadour who is thought to have been a Templar. The poem is in reference to some battles in 1265 that were not going well for the Crusaders: "And daily they impose new defeats on us: for God, who used to watch on our behalf, is now asleep, and Muhammad [Bafometz] puts forth his power to support the Sultan.[8]

Eliphas Levi and Baphomet

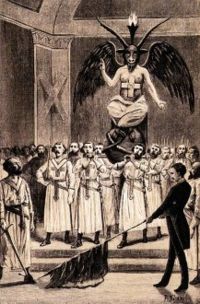

In the 19th century, the name of Baphomet became associated with the occult. In 1854, Eliphas Levi published Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie ("Dogmas and Rituals of High Magic"), in which he included an image he had drawn himself which he described as Baphomet and "The Sabbatic Goat", showing a winged humanoid goat with a pair of breasts and a torch on its head between its horns (illustration, top). This image has become the best-known representation of Baphomet. Levi's depiction is similar to that of the Devil in early tarot cards, but it may also have been partly inspired by grotesque carvings on the Templar churches of Lanleff in Brittany and St. Merri in Paris, which depict squatting bearded men with bat wings, female breasts, horns and the shaggy hindquarters of a beast.[9]

Lévi considered the Baphomet to be a depiction of the absolute in symbolic form and explicated in detail his symbolism in the drawing that served as the frontispiece:

- "The goat on the frontispiece carries the sign of the pentagram on the forehead, with one point at the top, a symbol of light, his two hands forming the sign of hermetism, the one pointing up to the white moon of Chesed, the other pointing down to the black one of Geburah. This sign expresses the perfect harmony of mercy with justice. His one arm is female, the other male like the ones of the androgyn of Khunrath, the attributes of which we had to unite with those of our goat because he is one and the same symbol. The flame of intelligence shining between his horns is the magic light of the universal balance, the image of the soul elevated above matter, as the flame, whilst being tied to matter, shines above it. The beast's head expresses the horror of the sinner, whose materially acting, solely responsible part has to bear the punishment exclusively; because the soul is insensitive according to its nature and can only suffer when it materializes. The rod standing instead of genitals symbolizes eternal life, the body covered with scales the water, the semi-circle above it the atmosphere, the feathers following above the volatile. Humanity is represented by the two breasts and the androgyn arms of this sphinx of the occult sciences."

Levi called his image “the Baphomet of Mendes”, presumably following Herodotus' account[10] that the god of Mendes — the Greek name for Djedet, Egypt — was depicted with a goat's face and legs. Herodotus relates how all male goats were held in great reverence by the Mendesians, and how in his time a woman publicly copulated with a goat.[11] However the deity that was venerated at Egyptian Mendes was actually a ram deity Banebdjed (literally Ba of the lord of djed, and titled "the Lord of Mendes"), who was the soul of Osiris. Levi combined the images of the Tarot of Marseilles Devil card and refigured the ram Banebdjed as a he-goat, further imagined by him as "copulator in Anep and inseminator in the district of Mendes".

Aleister Crowley and Baphomet

The Baphomet of Lévi was to become an important figure within the cosmology of Thelema, the mystical system established by Aleister Crowley in the early twentieth century. He linked the ram-god of Mendes with the syncretic Ptolemaic-Roman Harpocrates, a version of the child-form of the Egyptian god Horus. Harpocrates was a granter of fertility, but he was not associated with debauch or lust—and, most important, in animal-form, he was a ram, not a buck goat. Crowley however, identified Baphomet with Harpocrates and also with what he called the Lion-Serpent. Crowley agreed that Baphomet was a divine androgyne and "the hieroglyph of arcane perfection"[12]. In The Law is for All[13] Crowley identifies the Lion-Serpent with one's "Secret Self", which he also called the Holy Guardian Angel.

In Magick (Book 4), Crowley writes, "The Devil does not exist. It is a false name invented by the Black Brothers to imply a Unity in their ignorant muddle of dispersions. A devil who had unity would be a God... 'The Devil' is, historically, the God of any people that one personally dislikes... This serpent, SATAN, is not the enemy of Man, but He who made Gods of our race, knowing Good and Evil; He bade 'Know Thyself!' and taught Initiation. He is 'The Devil' of the Book of Thoth, and His emblem is BAPHOMET, the Androgyne who is the hieroglyph of arcane perfection... He is therefore Life, and Love. But moreover his letter is ayin, the Eye, so that he is Light; and his Zodiacal image is Capricornus, that leaping goat whose attribute is Liberty." [14]

For Crowley, Baphomet is further a representative of the spiritual nature of the spermatozoa while also being symbolic of the "magical child" produced as a result of sex magic. As such, Baphomet represents the Union of Opposites, especially as mystically personified in Chaos and Babalon combined and biologically manifested with the sperm and egg united in the zygote.

Baphomet as a demon

Baphomet, as Lévi's illustration suggests, has occasionally been portrayed as a synonym of Satan or a demon, a member of the hierarchy of Hell. Baphomet appears in that guise as a character in James Blish's The Day After Judgment. Christian evangelist Jack Chick claims that Baphomet is a demon worshipped by Freemasons, a claim that apparently originated with the Taxil hoax.[15]. Léo Taxil's elaborate hoax employed a version of Lévi's Baphomet on the cover of Les Mystères de la franc-maçonnerie dévoilés, his lurid paperback "exposé" of Freemasonry, which in 1897 he revealed as a hoax satirizing ultra-Catholic anti-Masonic propaganda. Lévi's Baphomet is clearly the source as well of the later Tarot image of the Devil, in the Rider-Waite design. The downward-pointing pentagram on its forehead is enlarged upon by Lévi in his illustration of a goat's head arranged within such a pentagram, which he contrasts with the microcosmic man arranged within a similar but upright pentagram.[16]

The symbol of the goat in the downward-pointed pentagram was adopted as the official symbol—called the Sigil of Baphomet—of the Church of Satan, and continues to be used amongst Satanists.

Alternative Etymologies

While modern scholars such as Peter Partner, Dr. Malcolm Barber, and the Oxford English Dictionary, state that the origin of the name Baphomet was a probable French version of "Mahomet" (i.e., "Muhammad").[1][8] alternative etymologies have also been proposed:

- Emile Littré (1801–1881) in Dictionnaire de la langue francaise asserted that the word was cabalistically formed by writing backward tem. o. h. p. ab an abbreviation of templi omnium hominum pacis abbas, 'abbot' or 'father of the temple of peace of all men.' His source is the "Abbé Constant", which is to say, Alphonse-Louis Constant, the real name of Eliphas Lévi.

- Idries Shah proposed that "Baphomet" may derive from the Arabic word ابو فهمة Abufihamat, meaning "The Father of Understanding".[17]

- Atbash cipher for Sophia. Dr Hugh J. Schonfield,[18] one of the scholars who worked on the Dead Sea Scrolls, argued in his book The Essene Odyssey that the word "Baphomet" was created with knowledge of the Atbash substitution cipher, which substitutes the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet for the last, the second for the second last, and so on. "Baphomet" rendered in Hebrew is בפומת; interpreted using Atbash, it becomes שופיא, which can be interpreted as the Greek word "Sophia", or wisdom. This theory is an important part of the plot of The Da Vinci Code. Professor Schonfield's theory however cannot be independently corroborated.

- The Rev. Alphonsus Joseph-Mary Augustus Montague Summers (1880–1948), compiler of The History of Witchcraft and Demonology (1926) and The Geography of Witchcraft (1927) was able to form Baphomet from the Greek words 'baphe and 'Metis'. The two words together would mean "Baptism of Wisdom".

- Another theory is that "Baphomet" is a symbol of the severed head of John the baptist. John the baptist was revered by Knights Templar.

See also

- Sigil of Baphomet

- Bahamut

- Behemoth

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Malcolm Barber, p. 321

- ↑ Read, p. 266

- ↑ National Geographic Channel. Knights Templar, February 22, 2006 video documentary. Written by Jesse Evans

- ↑ Martin, p. 119

- ↑ Karen Ralls, Knights Templar Encyclopedia: The Essential Guide to the People, Places, Events, and Symbols of the Order of the Temple (New Page Books, 2007).

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary; Helen Nicholson, The Knights Templar, A New History (Sutton) 2001:242.

- ↑ The OED reports "Baphomet" as a medieval form of Mahomet, but does not find a first appearance in English until Henry Hallam, The View of the State of Europe during the Middle Ages, which also appeared in 1818.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Peter Partner (1987). The Knights Templar and Their Myth. pp. 34-35. ISBN 0-89281-273-7. (previously titled The Murdered Magicians)

- ↑ Jackson, Nigel & Michael Howard (2003). The Pillars of Tubal Cain. Milverton, Somerset: Capall Bann Publishing. p. 223.; Comparison of these images from about.com.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories ii. 42, 46 and 166.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories ii. 156.

- ↑ Magick, Ch.21

- ↑ Magick, p. 95.

- ↑ "Magick: Liber ABA: Book Four: Parts I–IV by Aleister Crowley with Mary Desti and Leila Waddell, Weiser Books, 1997"

- ↑ "Leo Taxil's confession".

- ↑ What do the symbols hide? Retrieved 28 June 2006.

- ↑ Daraul, Arkon. A History of Secret Societies. ISBN 0-8065-0857-4.. "Arkon Daraul" is widely thought to be a pseudonym of Idries Shah

- ↑ Hugh J. Schonfield, The Essene Odyssey. Longmead, Shaftesbury, Dorset SP7 8BP, England: Element Books Ltd., 1984; 1998 paperback reissue, p.164.

References

- Barber, Malcolm (1994), The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple, Cambridge

- Crowley, Aleister (1974), written at New York, NY, Equinox of the Gods, Gordon Press, <http://www.hermetic.com/crowley/eoftg/index.html>

- Crowley, Aleister (1981), written at New York, NY, The Book of Thoth, Weiser, <http://altreligion.about.com/library/texts/bl_thoth.htm>

- Crowley, Aleister (1996), written at Tempe, AZ, The Law is for All, New Falcon Publications, <http://www.amazon.com/dp/1561840904/>

- Crowley, Aleister (1997), written at York Beach, ME, Magick: Book 4, Weiser, <http://www.hermetic.com/crowley/libers/lib4.html>

- Martin, Sean (2005), The Knights Templar: The History & Myths of the Legendary Military Order. ISBN 1-56025-645-1.

- Read, Piers Paul (1999), The Templars. Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-306-81071-9.

- Franz Spunda. Baphomet: Der geheime Gott der Templer : ein alchimistischer Roman. ISBN 3-8655-2073-1

- Return to House on Haunted Hill. The Baphomet Idol is supposedly the cause behind the House's disturbing qualities.