Bengali language

| Bengali বাংলা Bangla |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spoken in: | Bangladesh, India, and several others | |||

| Region: | Eastern South Asia | |||

| Total speakers: | 230 million (189 million native) [1] | |||

| Ranking: | 6,[2] 5,[3] | |||

| Language family: | Indo-European Indo-Iranian Indo-Aryan Eastern Group Bengali-Assamese Bengali |

|||

| Writing system: | Bengali script | |||

| Official status | ||||

| Official language in: | ||||

| Regulated by: | Bangla Academy (Bangladesh) Paschimbanga Bangla Akademi (West Bengal) |

|||

| Language codes | ||||

| ISO 639-1: | bn | |||

| ISO 639-2: | ben | |||

| ISO 639-3: | ben | |||

|

||||

|

||||

Bengali or Bangla (IPA: [ˈbaŋla] বাংলা) is an Indo-Aryan language of the eastern Indian subcontinent, evolved from the Magadhi Prakrit and Sanskrit languages.

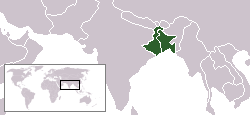

Bengali is native to the region of eastern South Asia known as Bengal, which comprises present day Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal and Assam mostly in the districts of Cachar, Karimganj, Hailakandi, Dhubri, Goalpara and Naogaon. With nearly 230 million total speakers, Bengali is one of the most spoken languages (ranking fifth[3] or sixth[2] in the world). Bengali is the primary language spoken in Bangladesh and is the second most spoken language in India.[4][5] Along with Assamese, it is geographically the most eastern of the Indo-Iranian languages.

With its long and rich literary tradition, Bengali serves to bind together a culturally diverse region. In 1952, when Bangladesh used to be East Pakistan, this strong sense of identity led to the Bengali Language Movement, in which several people braved bullets and died on February 21. This day has now been declared as the International Mother Language Day.

Contents |

History

Like other Eastern Indo-Aryan languages, Bengali arose from the eastern Middle Indic languages of the Indian subcontinent. Magadhi Prakrit and Maithili, the earliest recorded spoken language in the region and the language of the Buddha, had evolved into Ardhamagadhi ("Half Magadhi") in the early part of the first millennium CE.[6][7] Ardhamagadhi, as with all of the Prakrits of North India, began to give way to what are called Apabhramsa languages just before the turn of the first millennium.[8] The local Apabhramsa language of the eastern subcontinent, Purvi Apabhramsa or Apabhramsa Abahatta, eventually evolved into regional dialects, which in turn formed three groups: the Bihari languages, the Oriya languages, and the Bengali-Assamese languages. Some argue for much earlier points of divergence—going back to even 500[9] but the language was not static; different varieties coexisted and authors often wrote in multiple dialects. For example, Magadhi Prakrit is believed to have evolved into Apabhramsa Abahatta around the 6th century which competed with Bengali for a period of time.[10]

Usually three periods are identified in the history of Bengali:[8]

- Old Bengali (900/1000–1400)—texts include Charyapada, devotional songs; emergence of pronouns Ami, tumi, etc; verb inflections -ila, -iba, etc. Oriya and Assamese branch out in this period.

- Middle Bengali (1400–1800)—major texts of the period include Chandidas's Srikrishnakirtan; elision of word-final ô sound; spread of compound verbs; Persian influence. Some scholars further divide this period into early and late middle periods.

- New Bengali (since 1800)—shortening of verbs and pronouns, among other changes (e.g. tahar → tar "his"/"her"; koriyachhilô → korechhilo he/she had done).

Historically closer to Pali, Bengali saw an increase in Sanskrit influence during the Middle Bengali (Chaitanya era), and also during the Bengal Renaissance.[11] Of the modern Indo-European languages in South Asia, Bengali and Marathi maintain a largely Sanskrit vocabulary base while Hindi and others such as Punjabi are more influenced by Arabic and Persian.[12]

Until the 18th century, there was no attempt to document the grammar for Bengali. The first written Bengali dictionary/grammar, Vocabolario em idioma Bengalla, e Portuguez dividido em duas partes, was written by the Portuguese missionary Manoel da Assumpcam between 1734 and 1742 while he was serving in Bhawal.[13] Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, a British grammarian, wrote a modern Bengali grammar (A Grammar of the Bengal Language (1778)) that used Bengali types in print for the first time.[1] Raja Ram Mohan Roy, the great Bengali reformer,[14] also wrote a "Grammar of the Bengali Language" (1832).

During this period, the Choltibhasha form, using simplified inflections and other changes, was emerging from Shadhubhasha (older form) as the form of choice for written Bengali.[15]

Bengali was the focus, in 1951–52, of the Bengali Language Movement (Bhasha Andolon) in what was then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).[16] Although Bengali language was spoken by majority of Pakistan's population, Urdu was legislated as the sole national language.[17] On February 21, 1952, protesting students and activists were fired upon by military and police in Dhaka University and three young students and several other people were killed.[18] Later in 1999, UNESCO decided to celebrate every 21 February as International Mother Language Day in recognition of the deaths of the three students.[19][20] In a separate event in May 1961, police in Silchar, India, killed eleven people who were protesting legislation that mandated the use of the Assamese language.[21]

Geographical distribution

Bengali is native to the region of eastern South Asia known as Bengal, which comprises Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal and many parts of Assam. Around 98% of the total population of Bangladesh speak Bengali as a native language.[22] There are also significant Bengali-speaking communities in the Middle East, Europe, North America and South-East Asia.

Official status

Bengali is the national and official language of Bangladesh and one of the 23 official languages recognised by the Republic of India.[23] It is the official language of the states of West Bengal and Tripura.[24] It is a major language in the Indian union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[25][26] It was made an official language of Sierra Leone in order to honour the Bangladeshi peacekeeping force from the United Nations stationed there.[27] It is also the co-official language of Assam, which has three predominantly Sylheti-speaking districts of southern Assam: Cachar, Karimganj, and Hailakandi.[28] The national anthems of both India and Bangladesh were written by the Bengali Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore.[29]

- See also: States of India by Bengali speakers

Dialects

Regional variation in spoken Bengali constitutes a dialect continuum. Linguist Suniti Kumar Chatterjee grouped these dialects into four large clusters—Rarh, Banga, Kamarupa and Varendra;[1] but many alternative grouping schemes have also been proposed.[30] The south-western dialects (Rarh) form the basis of standard colloquial Bengali, while Bangali is the dominant dialect group in Bangladesh. In the dialects prevalent in much of eastern and south-eastern Bengal (Barisal, Chittagong, Dhaka and Sylhet divisions of Bangladesh), many of the stops and affricates heard in West Bengal are pronounced as fricatives. Western palato-alveolar affricates চ [tʃ], ছ [tʃʰ], জ [dʒ] correspond to eastern চʻ [ts], ছ় [s], জʻ [dz]~[z]. The influence of Tibeto-Burman languages on the phonology of Eastern Bengali is seen through the lack of nasalized vowels. Some variants of Bengali, particularly Chittagonian and Chakma Bengali, have contrastive tone; differences in the pitch of the speaker's voice can distinguish words. Rajbangsi, Kharia Thar and Mal Paharia are closely related to Western Bengali dialects, but are typically classified as separate languages. Similarly, Hajong is considered a separate language, although it shares similarities to Northern Bengali dialects.[31]

During the standardization of Bengali in the late 19th and early 20th century, the cultural center of Bengal was in the British founded city of Kolkata (then Calcutta). What is accepted as the standard form today in both West Bengal and Bangladesh is based on the West-Central dialect of Nadia, an Indian district located on the border of Bangladesh.[32] There are cases where speakers of Standard Bengali in West Bengal will use a different word than a speaker of Standard Bengali in Bangladesh, even though both words are of native Bengali descent. For example, nun (salt) in the west corresponds to lôbon in the east.[33]

Spoken and literary varieties

Bengali exhibits diglossia between the written and spoken forms of the language.[34] Two styles of writing, involving somewhat different vocabularies and syntax, have emerged:[32][35]

- Shadhubhasha (সাধু shadhu = 'chaste' or 'sage'; ভাষা bhasha = 'language') was the written language with longer verb inflections and more of a Sanskrit-derived (তৎসম tôtshôm) vocabulary. Songs such as India's national anthem Jana Gana Mana (by Rabindranath Tagore) and national song Vande Mātaram (by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay) were composed in Shadhubhasha. However, use of Shadhubhasha in modern writing is negligible, except when it is used deliberately to achieve some effect.

- Choltibhasha (চলতিভাষা ) or Cholitobhasha (চলিত cholito = 'current' or 'running') , known by linguists as Manno Cholit Bangla (Standard Colloquial Bengali), is a written Bengali style exhibiting a preponderance colloquial idiom and shortened verb forms, and is the standard for written Bengali now. This form came into vogue towards the turn of the 19th century, promoted by the writings of Peary Chand Mitra (Alaler Gharer Dulal, 1857),[36] Pramatha Chowdhury (Sabujpatra, 1914) and in the later writings of Rabindranath Tagore. It is modeled on the dialect spoken in the Shantipur region in Nadia district, West Bengal. This form of Bengali is often referred to as the "Nadia standard" or "Shantipuri bangla".[30]

While most writings are carried out in Standard Colloquial Bengali, spoken dialects exhibit a greater variety. South-eastern West Bengal, including Kolkata, speak in Standard Colloquial Bengali. Other parts of West Bengal and western Bangladesh speak in dialects that are minor variations, such as the Medinipur dialect characterised by some unique words and constructions. However, a majority in Bangladesh speak in dialects notably different from Standard Colloquial Bengali. Some dialects, particularly those of the Chittagong region, bear only a superficial resemblance to Standard Colloquial Bengali.[37] The dialect in the Chattagram region is least widely understood by the general body of Bengalis.[37] The majority of Bengalis are able to communicate in more than one variety—often, speakers are fluent in cholitobhasha (Standard Colloquial Bengali) and one or more regional dialects.[15]

Even in Standard Colloquial Bengali, Muslims and Hindu use different words. Due to cultural and religious traditions, Hindus and Muslims might use, respectively, Sanskrit-derived and Perso-Arabic words.[38] Some examples of lexical alternation between these two forms are:[33]

- hello: nômoshkar (S) corresponds to assalamualaikum/slamalikum (A)

- invitation: nimontron/nimontonno (S) corresponds to daoat (A)

- water : jol (S) corresponds to pani (S)

(here S = derived from Sanskrit, D = deshi; A = derived from Arabic)

Writing system

The Bengali writing system is not purely alphabet-based such as the Latin script. Rather, it is written in the Bengali abugida, a variant of the Eastern Nagari script used throughout Bangladesh and eastern India. In India the Eastern Nagari script is used throughout Assam, West Bengal and the Mithila Region of State of Bihar. It is believed to have evolved from a modified Brahmic script around 1000,[39] and is similar to the Devanagari abugida used for Sanskrit and many modern Indic languages such as Hindi. It has particularly close historical relationships with the Assamese script, Mithilakshar also known as Tirhutakshar which is the original native script of Maithili language and the Oriya script (although the Oriya script is not evident in appearance). The Bengali abugida is a cursive script with eleven graphemes or signs denoting the independent form of nine vowels and two diphthongs, and thirty-nine signs denoting the consonants with the so called "inherent" vowels.[39] The concept of capitalization is absent in Bengali writing system. There is no variation in initial, medial and final forms as in the Arabic script. The letters run from left to right on a horizontal line, and spaces are used to separate orthographic words.

Although the consonant signs are presented as segments in the basic inventory of the Bengali script, they are actually orthographically syllabic in nature. Every consonant sign has the vowel অ [ɔ] (or sometimes the vowel ও [o]) "embedded" or "inherent" in it.[40] For example, the basic consonant sign ম is pronounced [mɔ] in isolation. The same ম can represent the sounds [mɔ] or [mo] when used in a word, as in মত [mɔt̪] "opinion" and মন [mon] "mind", respectively, with no added symbol for the vowels [ɔ] and [o].

A consonant sound followed by some vowel sound other than [ɔ] is orthographically realized by using a variety of vowel allographs above, below, before, after, or around the consonant sign, thus forming the ubiquitous consonant-vowel ligature. These allographs, called kars (cf. Hindi matras) are dependent vowel forms and cannot stand on their own. For example, the graph মি [mi] represents the consonant [m] followed by the vowel [i], where [i] is represented as the allograph ি and is placed before the default consonant sign. Similarly, the graphs মা [ma], মী [mi], মু [mu], মূ [mu], মৃ [mri], মে [me]/[mæ], মৈ [moj], মো [mo] and মৌ [mow] represent the same consonant ম combined with seven other vowels and two diphthongs. It should be noted that in these consonant-vowel ligatures, the so-called "inherent" vowel is expunged from the consonant, but the basic consonant sign ম does not indicate this change.

To emphatically represent a consonant sound without any inherent vowel attached to it, a special diacritic, called the hôshonto (্), may be added below the basic consonant sign (as in ম্ [m]). This diacritic, however, is not common, and is chiefly employed as a guide to pronunciation.

Three other commonly used diacritics in the Bengali are the superposed chôndrobindu (ঁ), denoting a suprasegmental for nasalization of vowels (as in চাঁদ [tʃãd] "moon"), the postposed onushshôr (ং) indicating the velar nasal [ŋ] (as in বাংলা [baŋla] "Bengali") and the postposed bishôrgo (ঃ) indicating the voiceless glottal fricative [h] (as in উঃ! [uh] "ouch!").

The vowel signs in Bengali can take two forms: the independent form found in the basic inventory of the script and the dependent, abridged, allograph form (as discussed above). To represent a vowel in isolation from any preceding or following consonant, the independent form of the vowel is used. For example, in মই [moj] "ladder" and in ইলিশ [iliʃ] "Hilsa fish", the independent form of the vowel ই is used (cf. the dependent form ি). A vowel at the beginning of a word is always realized using its independent form.

The Bengali consonant clusters (যুক্তাক্ষর juktakkhor in Bengali) are usually realized as ligatures, where the consonant which comes first is put on top of or to the left of the one that immediately follows. In these ligatures, the shapes of the constituent consonant signs are often contracted and sometimes even distorted beyond recognition. In Bengali writing system, there are nearly 285 such ligatures denoting consonant clusters. Many of their shapes have to be learned by rote. Recently, in a bid to lessen this burden on young learners, efforts have been made by educational institutions in the two main Bengali-speaking regions (West Bengal and Bangladesh) to address the opaque nature of many consonant clusters, and as a result, modern Bengali textbooks are beginning to contain more and more "transparent" graphical forms of consonant clusters, in which the constituent consonants of a cluster are readily apparent from the graphical form. However, since this change is not as widespread and is not being followed as uniformly in the rest of the Bengali printed literature, today's Bengali-learning children will possibly have to learn to recognize both the new "transparent" and the old "opaque" forms, which ultimately amounts to an increase in learning burden.

Bengali punctuation marks, apart from the daŗi (|), the Bengali equivalent of a full stop, have been adopted from Western scripts and their usage is similar. [1]

Whereas in western scripts (Latin, Cyrillic, etc.) the letter-forms stand on an invisible baseline, the Bengali letter-forms hang from a visible horizontal headstroke called the matra (not to be confused with its Hindi cognate matra, which denotes the dependent forms of Hindi vowels). The presence and absence of this matra can be important. For example, the letter ত [tɔ] and the numeral ৩ "3" are distinguishable only by the presence or absence of the matra, as is the case between the consonant cluster ত্র [trɔ] and the independent vowel এ [e]. The letter-forms also employ the concepts of letter-width and letter-height (the vertical space between the visible matra and an invisible baseline).

Spelling-to-pronunciation inconsistencies

In spite of some modifications in the nineteenth century, the Bengali spelling system continues to be based on the one used for Sanskrit,[1] and thus does not take into account some sound mergers that have occurred in the spoken language. For example, there are three letters (শ, ষ, and স) for the voiceless palato-alveolar fricative [ʃ], although the letter স does retain the voiceless alveolar fricative [s] sound when used in certain consonant conjuncts as in স্খলন [skʰɔlon] "fall", স্পন্দন [spɔndon] "beat", etc. There are two letters (জ and য) for the voiced postalveolar affricate [dʒ] as well. What was once pronounced and written as a retroflex nasal ণ [ɳ] is now pronounced as an alveolar [n] (unless conjoined with another retroflex consonant such as ট, ঠ, ড and ঢ), although the spelling does not reflect this change. The near-open front unrounded vowel [æ] is orthographically realized by multiple means, as seen in the following examples: এত [æt̪o] "so much", এ্যাকাডেমী [ækademi] "academy", অ্যামিবা [æmiba] "amoeba", দেখা [d̪ækha] "to see", ব্যস্ত [bæst̪o] "busy", ব্যাকরণ [bækɔron] "grammar".

The realization of the inherent vowel can be another source of confusion. The vowel can be phonetically realized as [ɔ] or [o] depending on the word, and its omission is seldom indicated, as in the final consonant in কম [kɔm] "less".

Many consonant clusters have different sounds than their constituent consonants. For example, the combination of the consonants ক্ [k] and ষ [ʃɔ] is graphically realized as ক্ষ and is pronounced [kʰːo] (as in রুক্ষ [rukʰːo] "rugged") or [kʰo] (as in ক্ষতি [kʰot̪i] "loss") or even [kʰɔ] (as in ক্ষমতা [kʰɔmot̪a] "power"), depending on the position of the cluster in a word. The Bengali writing system is, therefore, not always a true guide to pronunciation.

For a detailed list of these inconsistencies, consult Bengali script.

Uses in other languages

The Bengali script, with a few small modifications, is also used for writing Assamese. Other related languages in the region also make use of the Bengali alphabet. Meitei, a Sino-Tibetan language used in the Indian state of Manipur, has been written in the Bengali abugida for centuries, though Meitei Mayek (the Meitei abugida) has been promoted in recent times. The script has been adopted for writing the Sylheti language as well, replacing the use of the old Sylheti Nagori script.[41]

Romanization

Several conventions exist for writing Indic languages including Bengali in the Latin script, including "International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration" or IAST (based on diacritics),[42] "Indian languages Transliteration" or ITRANS (uses upper case alphabets suited for ASCII keyboards),[43] and the National Library at Calcutta romanization.[44]

In the context of Bangla Romanization, it is important to distinguish between transliteration from transcription. Transliteration is orthographically accurate (i.e. the original spelling can be recovered), whereas transcription is phonetically accurate (the pronunciation can be reproduced). Since English does not have the sounds of Bangla, and since pronunciation does not completely reflect the spellings, being faithful to both is not possible.

Although it might be desirable to use a transliteration scheme where the original Bangla orthography is recoverable from the Latin text, Bangla words are currently Romanized on Wikipedia using a phonemic transcription, where the pronunciation is represented with no reference to how it is written. The Wikipedia Romanization scheme is given in the table below, with the IPA transcriptions as used above.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sounds

The phonemic inventory of Bengali consists of 29 consonants and 14 vowels, including the seven nasalized vowels. An approximate phonetic scheme is set out below in International Phonetic Alphabet.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Diphthongs

Magadhan languages such as Bengali are known for their wide variety of diphthongs, or combinations of vowels occurring within the same syllable.[45] Several vowel combinations can be considered true monosyllabic diphthongs, made up of the main vowel (the nucleus) and the trailing vowel (the off-glide). Almost all other vowel combinations are possible, but only across two adjacent syllables, such as the disyllabic vowel combination [u.a] in কুয়া kua "well". As many as 25 vowel combinations can be found, but some of the more recent combinations have not passed through the stage between two syllables and a diphthongal monosyllable.[46]

| IPA | Transliteration | Example |

|---|---|---|

| /ij/ | ii | nii "I take" |

| /iw/ | iu | biubhôl "upset" |

| /ej/ | ei | nei "there is not" |

| /ee̯/ | ee | khee "having eaten" |

| /ew/ | eu | đheu "wave" |

| /eo̯/ | eo | kheona "do not eat" |

| /æe̯/ | êe | nêe "she takes" |

| /æo̯/ | êo | nêo "you take" |

| /aj/ | ai | pai "I find" |

| /ae̯/ | ae | pae "she finds" |

| /aw/ | au | pau "sliced bread" |

| /ao̯/ | ao | pao "you find" |

| /ɔe̯/ | ôe | nôe "she is not" |

| /ɔo̯/ | ôo | nôo "you are not" |

| /oj/ | oi | noi "I am not" |

| /oe̯/ | oe | dhoe "she washes" |

| /oo̯/ | oo | dhoo "you wash" |

| /ow/ | ou | nouka "boat" |

| /uj/ | ui | dhui "I wash" |

Stress

In standard Bengali, stress is predominantly initial. Bengali words are virtually all trochaic; the primary stress falls on the initial syllable of the word, while secondary stress often falls on all odd-numbered syllables thereafter, giving strings such as shô-ho-jo-gi-ta "cooperation", where the boldface represents primary and secondary stress. The first syllable carries the greatest stress, with the third carrying a somewhat weaker stress, and all following odd-numbered syllables carrying very weak stress. However in words borrowed from Sanskrit, the root syllable is stressed, causing them to be out of harmony with native Bengali words.[47]

Adding prefixes to a word typically shifts the stress to the left. For example, while the word shob-bho "civilized" carries the primary stress on the first syllable [shob], adding the negative prefix [ô-] creates ô-shob-bho "uncivilized", where the primary stress is now on the newly-added first syllable অ ô. In any case, word-stress does not alter the meaning of a word and is always subsidiary to sentence-stress.[47]

Intonation

For Bengali words, intonation or pitch of voice has minor significance, apart from a few isolated cases. However in sentences intonation does play a significant role.[48] In a simple declarative sentence, most words and/or phrases in Bengali carry a rising tone,[49] with the exception of the last word in the sentence, which only carries a low tone. This intonational pattern creates a musical tone to the typical Bengali sentence, with low and high tones alternating until the final drop in pitch to mark the end of the sentence.

In sentences involving focused words and/or phrases, the rising tones only last until the focused word; all following words carry a low tone.[49] This intonation pattern extends to wh-questions, as wh-words are normally considered to be focused. In yes-no questions, the rising tones may be more exaggerated, and most importantly, the final syllable of the final word in the sentence takes a high falling tone instead of a flat low tone.[50]

Vowel length

Vowel length is not contrastive in Bengali; all else equal, there is no meaningful distinction between a "short vowel" and a "long vowel",[51] unlike the situation in many other Indic languages. However, when morpheme boundaries come into play, vowel length can sometimes distinguish otherwise homophonous words. This is due to the fact that open monosyllables (i.e. words that are made up of only one syllable, with that syllable ending in the main vowel and not a consonant) have somewhat longer vowels than other syllable types.[52] For example, the vowel in cha: "tea" is somewhat longer than the first vowel in chaţa "licking", as cha: is a word with only one syllable, and no final consonant. (The long vowel is marked with a colon : in these examples.) The suffix ţa "the" can be added to cha: to form cha:ţa "the tea". Even when another morpheme is attached to cha:, the long vowel is preserved. Knowing this fact, some interesting cases of apparent vowel length distinction can be found. In general Bengali vowels tend to stay away from extreme vowel articulation.[52]

Furthermore, using a form of reduplication called "echo reduplication", the long vowel in cha: can be copied into the reduplicant ţa:, giving cha:ţa: "tea and all that comes with it". Thus, in addition to cha:ţa "the tea" (long first vowel) and chaţa "licking" (no long vowels), we have cha:ţa: "tea and all that comes with it" (both long vowels).

Consonant clusters

Native Bengali (tôdbhôbo) words do not allow initial consonant clusters;[53] the maximum syllabic structure is CVC (i.e. one vowel flanked by a consonant on each side). Many speakers of Bengali restrict their phonology to this pattern, even when using Sanskrit or English borrowings, such as গেরাম geram (CV.CVC) for গ্রাম gram (CCVC) "village" or ইস্কুল iskul (VC.CVC) for স্কুল skul (CCVC) "school".

Sanskrit (তৎসম tôtshômo) words borrowed into Bengali, however, possess a wide range of clusters, expanding the maximum syllable structure to CCCVC. Some of these clusters, such as the mr in মৃত্যু mrittu "death" or the sp in স্পষ্ট spôshţo "clear", have become extremely common, and can be considered legal consonant clusters in Bengali. English and other foreign (বিদেশী bideshi) borrowings add even more cluster types into the Bengali inventory, further increasing the syllable capacity to CCCVCCCC, as commonly-used loanwords such as ট্রেন ţren "train" and গ্লাস glash "glass" are now even included in leading Bengali dictionaries.

Final consonant clusters are rare in Bengali.[54] Most final consonant clusters were borrowed into Bengali from English, as in লিফ্ট lifţ "lift, elevator" and ব্যাংক bêņk "bank". However, final clusters do exist in some native Bengali words, although rarely in standard pronunciation. One example of a final cluster in a standard Bengali word would be গঞ্জ gônj, which is found in names of hundreds of cities and towns across Bengal, including নবাবগঞ্জ Nôbabgônj and মানিকগঞ্জ Manikgônj. Some nonstandard varieties of Bengali make use of final clusters quite often. For example, in some Purbo (eastern) dialects, final consonant clusters consisting of a nasal and its corresponding oral stop are common, as in চান্দ chand "moon". The Standard Bengali equivalent of chand would be চাঁদ chãd, with a nasalized vowel instead of the final cluster.

Grammar

Bengali nouns are not assigned gender, which leads to minimal changing of adjectives (inflection). However, nouns and pronouns are highly declined (altered depending on their function in a sentence) into four cases while verbs are heavily conjugated.

As a consequence, unlike Hindi, Bengali verbs do not change form depending on the gender of the nouns.

Word order

As a Head-Final language, Bengali follows Subject Object Verb word order, although variations to this theme are common.[55] Bengali makes use of postpositions, as opposed to the prepositions used in English and other European languages. Determiners follow the noun, while numerals, adjectives, and possessors precede the noun.[56]

Yes-no questions do not require any change to the basic word order; instead, the low (L) tone of the final syllable in the utterance is replaced with a falling (HL) tone. Additionally optional particles (e.g. কি -ki, না -na, etc.) are often encliticized onto the first or last word of a yes-no question.

Wh-questions are formed by fronting the wh-word to focus position, which is typically the first or second word in the utterance.

Nouns

Nouns and pronouns are inflected for case, including nominative, objective, genitive (possessive), and locative.[8] The case marking pattern for each noun being inflected depends on the noun's degree of animacy. When a definite article such as -টা -ţa (singular) or -গুলা -gula (plural) is added, as in the tables below, nouns are also inflected for number.

|

|

When counted, nouns take one of a small set of measure words. As in many East Asian languages (e.g. Chinese, Japanese, Thai, etc.), nouns in Bengali cannot be counted by adding the numeral directly adjacent to the noun. The noun's measure word (MW) must be used between the numeral and the noun. Most nouns take the generic measure word -টা -ţa, though other measure words indicate semantic classes (e.g. -জন -jon for humans).

| Bengali | Bengali transliteration | Literal translation | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| নয়টা গরু | Nôe-ţa goru | Nine-MW cow | Nine cows |

| কয়টা বালিশ | Kôe-ţa balish | How many-MW pillow | How many pillows |

| অনেকজন লোক | Ônek-jon lok | Many-MW person | Many people |

| চার-পাঁচজন শিক্ষক | Char-pãch-jon shikkhôk | Four-five-MW teacher | Four or five teachers |

Measuring nouns in Bengali without their corresponding measure words (e.g. আট বিড়াল aţ biŗal instead of আটটা বিড়াল aţ-ţa biŗal "eight cats") would typically be considered ungrammatical. However, when the semantic class of the noun is understood from the measure word, the noun is often omitted and only the measure word is used, e.g. শুধু একজন থাকবে। Shudhu êk-jon thakbe. (lit. "Only one-MW will remain.") would be understood to mean "Only one person will remain.", given the semantic class implicit in -জন -jon.

In this sense, all nouns in Bengali, unlike most other Indo-European languages, are similar to mass nouns.

Verbs

Verbs divide into two classes: finite and non-finite. Non-finite verbs have no inflection for tense or person, while finite verbs are fully inflected for person (first, second, third), tense (present, past, future), aspect (simple, perfect, progressive), and honor (intimate, familiar, and formal), but not for number. Conditional, imperative, and other special inflections for mood can replace the tense and aspect suffixes. The number of inflections on many verb roots can total more than 200.

Inflectional suffixes in the morphology of Bengali vary from region to region, along with minor differences in syntax.

Bengali differs from most Indo-Aryan Languages in the zero copula, where the copula or connective be is often missing in the present tense.[1] Thus "he is a teacher" is she shikkhôk, (literally "he teacher").[57] In this respect, Bengali is similar to Russian and Hungarian.

Vocabulary

Bengali has as many as 100,000 separate words, of which 50,000 are considered tôtshômo (direct reborrowings from Sanskrit), 21,100 are tôdbhôbo (native words with Sanskrit cognates), and the rest being bideshi (foreign borrowings) and deshi (Austroasiatic borrowings) words.

However, these figures do not take into account the fact that a large proportion of these words are archaic or highly technical, minimizing their actual usage. The productive vocabulary used in modern literary works, in fact, is made up mostly (67%) of tôdbhôbo words, while tôtshômo only make up 25% of the total.[58][59] Deshi and Bideshi words together make up the remaining 8% of the vocabulary used in modern Bengali literature.

Due to centuries of contact with Europeans, Mughals, Arabs, Turks, Persians, Afghans, and East Asians, Bengali has incorporated many words from foreign languages. The most common borrowings from foreign languages come from three different kinds of contact. Close contact with neighboring peoples facilitated the borrowing of words from Hindi, Assamese and several indigenous Austroasiatic languages (like Santali).[60] of Bengal. After centuries of invasions from Persia and the Middle East, numerous Persian, Arabic, Turkish, and Pashtun words were absorbed into Bengali. Portuguese, French, Dutch and English words were later additions during the colonial period.

Sample audio

Sample text

The following is a sample text in Bengali of the Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (by the United Nations):

Bengali in Eastern Nagari script

- ধারা ১: সমস্ত মানুষ স্বাধীনভাবে সমান মর্যাদা এবং অধিকার নিয়ে জন্মগ্রহণ করে। তাঁদের বিবেক এবং বুদ্ধি আছে; সুতরাং সকলেরই একে অপরের প্রতি ভ্রাতৃত্বসুলভ মনোভাব নিয়ে আচরণ করা উচিৎ।

Bengali in Romanization

- Dhara êk: Shômosto manush shadhinbhabe shôman môrjada ebong odhikar nie jônmogrohon kôre. Tãder bibek ebong buddhi achhe; shutorang shôkoleri êke ôporer proti bhrattrittoshulôbh mônobhab nie achorôn kôra uchit.

Bengali in IPA

- d̪ɦara æk: ʃɔmost̪o manuʃ ʃad̪ɦinbɦabe ʃɔman mɔrdʒad̪a eboŋ od̪ɦikar nie dʒɔnmogrohon kɔre. t̪ãd̪er bibek eboŋ bud̪ɦːi atʃʰe; ʃut̪oraŋ ʃɔkoleri æke ɔporer prot̪i bɦrat̪ːrit̪ːoʃulɔbɦ mɔnobɦab nie atʃorɔn kɔra utʃit̪.

Gloss

- Clause 1: All human free-manner-in equal dignity and right taken birth-take do. Their reason and intelligence have; therefore everyone-indeed one another's towards brotherhood-ly attitude taken conduct do should.

Translation

- Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience. Therefore, they should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

See also

|

|||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Bangla language in Asiatic Society of Bangladesh 2003

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Languages spoken by more than 10 million people". Encarta Encyclopedia (2007). Retrieved on 2007-03-03.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Statistical Summaries". Ethnologue (2005). Retrieved on 2007-03-03.

- ↑ Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed. (2005). "Languages of India". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition.. SIL International. Retrieved on 2006-11-17.

- ↑ "Languages in Descending Order of Strength - India, States and Union Territories - 1991 Census". Census Data Online 1. Office of the Registrar General, India. Archived from the original on 2007-06-14. Retrieved on 2006-11-19.

- ↑ Shah 1998, p. 11

- ↑ Keith 1998, p. 187

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 (Bhattacharya 2000)

- ↑ (Sen 1996)

- ↑ Abahattha in Asiatic Society of Bangladesh 2003

- ↑ Tagore & Das 1996, p. 222

- ↑ Chisholm 1910, p. 489

- ↑ Rahman, Aminur. "Grammar". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Retrieved on 2006-11-19.

- ↑ Wilson & Dalton 1982, p. 155

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ray, S Kumar. "The Bengali Language and Translation". Translation Articles. Kwintessential. Retrieved on 2006-11-19.

- ↑ Baxter 1997, pp. 62–63

- ↑ Ali & Rehman 2001, p. 25

- ↑ "Dhaka Medical College Hostel Prangone Chatro Shomabesher Upor Policer Guliborshon. Bishwabidyalayer Tinjon Chatroshoho Char Bekti Nihoto O Shotero Bekti Ahoto" (in Bengali), The Azad (22 February 1952).

- ↑ "Amendment to the Draft Programme and Budget for 2000-2001 (30 C/5)" (PDF). General Conference, 30th Session, Draft Resolution. UNESCO (1999). Retrieved on 2008-05-27.

- ↑ "Resolution adopted by the 30th Session of UNESCO's General Conference (1999)". International Mother Language Day. UNESCO. Retrieved on 2008-05-27.

- ↑ "No alliance with BJP, says AGP chief". The Telegraph. Retrieved on 2006-11-19.

- ↑ "The World Fact Book". CIA. Retrieved on 2006-11-04.

- ↑ "Languages of India". Ethnologue Report. Retrieved on 2006-11-04.

- ↑ Bhattacharjee, Kishalay (April 30 2008). "It's Indian language vs Indian language", ndtv.com. Retrieved on 2008-05-27.

- ↑ "Profile: A&N Islands at a Glance". Andaman District. National Informatics Center. Retrieved on 2008-05-27.

- ↑ "Andaman District". Andaman & Nicobar Police. National Informatics Center. Retrieved on 2008-05-27.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone makes Bengali official language", Daily Times (2002-12-29). Retrieved on 2006-11-17.

- ↑ NIC, Assam State Centre, Guwahati, Assam. "Language". Government of Assam. Archived from the original on 2006-12-06. Retrieved on 2006-06-20.

- ↑ "Statement by Hon'ble Foreign Minister on Second Bangladesh-India Track II dialogue at BRAC Centre on 07 August, 2005". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Bangladesh. Retrieved on 2008-05-27.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Morshed, Abul Kalam Manjoor. "Dialect". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Retrieved on 2006-11-17.

- ↑ "Hajong". The Ethnologue Report. Retrieved on 2006-11-19.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Huq, Mohammad Daniul. "Chalita Bhasa". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Retrieved on 2006-11-17.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "History of Bangla (Banglar itihash)". Bangla. Bengal Telecommunication and Electric Company. Retrieved on 2006-11-20.

- ↑ "Bengali Language At Cornell: Language Information". Department of Asian Studies at Cornell University. Cornell University. Retrieved on 2008-05-27.

- ↑ Huq, Mohammad Daniul. "Sadhu Bhasa". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Retrieved on 2006-11-17.

- ↑ Huq, Mohammad Daniul. "Alaler Gharer Dulal". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Retrieved on 2006-11-17.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Ray, Hai & Ray 1966, p. 89

- ↑ Ray, Hai & Ray 1966, p. 80

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Bangla Script in Asiatic Society of Bangladesh 2003

- ↑ Escudero Pascual Alberto (2005-10-23). "Writing Systems/ Scripts" (PDF). Primer to Localization of Software. IT +46. Retrieved on 2006-11-20.

- ↑ Islam, Muhammad Ashraful. "Sylheti Nagri". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Retrieved on 2006-11-17.

- ↑ "Learning International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration". Sanskrit 3 - Learning transliteration. Gabriel Pradiipaka & Andrés Muni. Archived from the original on 2007-02-12. Retrieved on 2006-11-20.

- ↑ "ITRANS - Indian Language Transliteration Package". Avinash Chopde. Retrieved on 2006-11-20.

- ↑ "Annex-F: Roman Script Transliteration" (PDF). Indian Standard: Indian Script Code for Information Interchange - ISCII 32. Bureau of Indian Standards (1999-04-01). Retrieved on 2006-11-20.

- ↑ (Masica 1991, pp. 116)

- ↑ (Chatterji 1926, pp. 415–416)

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 (Chatterji 1921, pp. 19–20)

- ↑ (Chatterji 1921, pp. 20)

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Hayes & Lahiri 1991, pp. 56

- ↑ Hayes & Lahiri 1991, pp. 57–58

- ↑ (Bhattacharya 2000, pp. 6)

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 (Ferguson & Chowdhury 1960, pp. 16–18)

- ↑ (Masica 1991, pp. 125)

- ↑ (Masica 1991, pp. 126)

- ↑ (Bhattacharya 2000, pp. 16)

- ↑ "Bengali". UCLA Language Materials project. University of California, Los Angeles. Retrieved on 2006-11-20.

- ↑ Among Bengali speakers brought up in neighbouring linguistic regions (e.g. Hindi), the lost copula may surface in utterances such as she shikkhôk hochchhe. This is viewed as ungrammatical by other speakers, and speakers of this variety are sometimes (humorously) referred as "hochchhe-Bangali".

- ↑ Tatsama in Asiatic Society of Bangladesh 2003

- ↑ Tatbhava in Asiatic Society of Bangladesh 2003

- ↑ Byomkes Chakrabarti A Comparative Study of Santali and Bengali, K.P. Bagchi & Co., Kolkata, 1994, ISBN 8170741289

References

|

|

External links

- Ethnologue report for Bengali

- Bengali Language: A Brief Introduction

- Samsad Bengali-English dictionary. 3rd ed. online. Requires unicode enabled browser.

- Free Bangla Unicode Solutions.

- The South Asian Literary Recordings Project, The Library of Congress. Bengali Authors.

|

||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||