Back pain

| Back pain Classification and external resources |

|

|

|

|---|---|

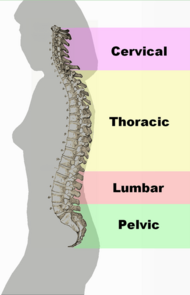

| Different regions (curvatures) of the vertebral column | |

| ICD-10 | M54. |

| ICD-9 | 724.5 |

| DiseasesDB | 15544 |

| MeSH | D001416 |

Back pain (also known "dorsalgia") is pain felt in the back that usually originates from the muscles, nerves, bones, joints or other structures in the spine.

The pain may have a sudden onset or can be a chronic pain; it can be constant or intermittent, stay in one place or radiate to other areas. It may be a dull ache, or a sharp or piercing or burning sensation. The pain may be felt in the neck (and might radiate into the arm and hand), in the upper back, or in the low back, (and might radiate into the leg or foot), and may include symptoms other than pain, such as weakness, numbness or tingling.

Back pain is one of humanity's most frequent complaints. In the U.S., acute low back pain (also called lumbago) is the fifth most common reason for physician visits. About nine out of ten adults experience back pain at some point in their life, and five out of ten working adults have back pain every year.[1]

The spine is a complex interconnecting network of nerves, joints, muscles, tendons and ligaments, and all are capable of producing pain. Large nerves that originate in the spine and go to the legs and arms can make pain radiate to the extremities.

Contents |

Associated conditions

Back pain can be a sign of a serious medical problem, although this is not most frequently the underlying cause:

- Typical warning signs of a potentially life-threatening problem are bowel and/or bladder incontinence or progressive weakness in the legs.

- Severe back pain (such as pain that is bad enough to interrupt sleep) that occurs with other signs of severe illness (e.g. fever, unexplained weight loss) may also indicate a serious underlying medical condition.

- Back pain that occurs after a trauma, such as a car accident or fall may indicate a bone fracture or other injury.

- Back pain in individuals with medical conditions that put them at high risk for a spinal fracture, such as osteoporosis or multiple myeloma, also warrants prompt medical attention.

- Back pain in individuals with a history of cancer (especially cancers known to spread to the spine like breast, lung and prostate cancer) should be evaluated to rule out metastatic disease of the spine.

Back pain does not usually require immediate medical intervention. The vast majority of episodes of back pain are self-limiting and non-progressive. Most back pain syndromes are due to inflammation, especially in the acute phase, which typically lasts for two weeks to three months.

A few observational studies suggest that two conditions to which back pain is often attributed, lumbar disc herniation and degenerative disc disease may not be more prevalent among those in pain than among the general population, and that the mechanisms by which these conditions might cause pain are not known.[2][3][4][5] Other studies suggest that for as many as 85% of cases, no physiological cause can be shown.[6][7]

A few studies suggest that psychosocial factors such as on-the-job stress and dysfunctional family relationships may correlate more closely with back pain than structural abnormalities revealed in x-rays and other medical imaging scans.[8][9][10][11]

Underlying causes

Muscle strains (pulled muscles) are commonly identified as the cause of back pain, as are muscle imbalances. Pain from such an injury often remains as long as the muscle imbalances persist. The muscle imbalances cause a mechanical problem with the skeleton, building up pressure at points along the spine, which causes the pain.

Another cause of acute low back pain is a meniscoid occlusion. The more mobile regions of the spine, such as the facet joints, have invaginations of their synovial membranes that act as a cushion to help the bones move over each other smoothly. The synovial membrane is well supplied with blood and nerves. When these become pinched or trapped sudden severe pain may result. The pinching causes the membrane to become inflamed, causing greater pressure and ongoing pain. Symptoms include severe low back pain that may be accompanied by muscle spasm, pain with walking, concentration of pain to one side, but no radiculopathy (radiating pain down buttock and leg). Relief should be felt with flexion (bending forward), and exacerbated with extension (bending backward).

When back pain lasts more than three months, or if there is more radicular pain (sciatica) than back pain, a more specific diagnosis can usually be made. There are several common causes of back pain: for adults under age 50, these include spinal disc herniation and degenerative disc disease or isthmic spondylolisthesis; in adults over age 50, common causes also include osteoarthritis (degenerative joint disease) and spinal stenosis, trauma, cancer, infection, fractures, and inflammatory disease[1]. Non-anatomical factors can also contribute to or cause back pain, such as stress,[12] repressed anger,[13] or depression. Even if there is an anatomical cause for the pain, if depression is present it should also be treated concurrently.

New attention has been focused on non-discogenic back pain, where patients have normal or near-normal MRI and CT scans. One of the newer investigations looks into the role of the dorsal ramus in patients that have no radiographic abnormalities. See Posterior Rami Syndrome.

Treatment

The management goals when treating back pain are to achieve maximal reduction in pain intensity as rapidly as possible; to restore the individual's ability to function in everyday activities; to help the patient cope with residual pain; to assess for side-effects of therapy; and to facilitate the patient's passage through the legal and socioeconomic impediments to recovery. For many, the goal is to keep the pain to a manageable level to progress with rehabilitation, which then can lead to long term pain relief. Also, for some people the goal is to use non-surgical therapies to manage the pain and avoid major surgery, while for others surgery may be the quickest way to feel better.

Not all treatments work for all conditions or for all individuals with the same condition, and many find that they need to try several treatment options to determine what works best for them. The present stage of the condition (acute or chronic) is also a determining factor in the choice of treatment. Only a minority of back pain patients (most estimates are 1% - 10%) require surgery.

Conservative treatment

- Heat therapy is useful for back spasms or other conditions. A meta-analysis of studies by the Cochrane Collaboration concluded that heat therapy can reduce symptoms of acute and sub-acute low-back pain.[14] Some patients find that moist heat works best (e.g. a hot bath or whirlpool) or continuous low-level heat (e.g. a heat wrap that stays warm for 4 to 6 hours). Cold compression therapy (e.g. ice or cold pack application) may be effective at relieving back pain in some cases.

- Use of medications, such as muscle relaxants,[15] narcotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs/NSAIAs)[16] or paracetamol (acetaminophen). A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials by the Cochrane Collaboration found that injection therapy, usually with corticosteroids, does not appear to help regardless of whether the injection is facet joint, epidural or a local injection.[17] Accordingly, a study of intramuscular corticosteroids found no benefit.[18]

- Exercises can be an effective approach, particularly when done under supervision of a licensed health professional. Generally, some form of consistent stretching and exercise is believed to be an essential component of most back treatment programs. However, one study found that exercise is also effective for chronic back pain, but not for acute pain.[19] Another study found that back-mobilizing exercises in acute settings are less effective than continuation of ordinary activities as tolerated.[20]

- Physical therapy and exercise, including stretching and strengthening (with specific focus on the muscles which support the spine), often learned with the help of a health professional, such as a physical therapist. Physical therapy may be especially effective when part of a 'work hardening' program, or 'back school'.[21]

- Massage therapy, especially from an experienced therapist, may help. Acupressure or pressure point massage may be more beneficial than classic (Swedish) massage.[22]

- Body Awareness Therapy such as the Feldenkrais Method has been studied in relation to Fibromyalgia and chronic pain and studies have indicated positive effects.[23]. Organized exercise programs using these therapies have been developed. The Alexander Technique was shown in a UK clinical trial to have long term benefits for patients with chronic back pain.[24]

- Manipulation, as provided by an appropriately trained and qualified chiropractor, osteopath, physical therapist, or a physiatrist. Studies of the effect of manipulation suggest that this approach has a benefit similar to other therapies and superior to placebo.[25][26]

- Acupuncture has some proven benefit for back pain [2]; however, a recent randomized controlled trial suggested insignificant difference between real and sham acupuncture [3].

- Education, and attitude adjustment to focus on psychological or emotional causes[27] - respondent-cognitive therapy and progressive relaxation therapy can reduce chronic pain.[28]

Surgery

Surgery may sometimes be appropriate for patients with:

- Lumbar disc herniation or degenerative disc disease

- Spinal stenosis from lumbar disc herniation, degenerative joint disease, or spondylolisthesis

- Scoliosis

- Compression fracture

Emerging treatments

- Vertebroplasty involves the percutaneous injection of surgical cement into vertebral bodies that have collapsed due to compression fractures. This new procedure is far less invasive than surgery, but may be complicated by the entry of cement into Batson's plexus with subsequent spread to the lungs or into the spinal canal. Ideally this procedure can result in rapid pain relief.

- The use of specific biologic inhibitors of the inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha may result in rapid relief of disc-related back pain. [29]

Treatments with uncertain or doubtful benefit

- Injections, such as epidural steroid injections and facet joint injections, may be effective when the cause of the pain is accurately localized to particular sites. The benefit of prolotherapy has not been well-documented.[17][30]

- Cold compression therapy is advocated for a strained back or chronic back pain and is postulated to reduce pain and inflammation, especially after strenuous exercise such as golf, gardening, or lifting. However, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials by the Cochrane Collaboration concluded "The evidence for the application of cold treatment to low-back pain is even more limited, with only three poor quality studies located. No conclusions can be drawn about the use of cold for low-back pain"[14]

- Bed rest is rarely recommended as it can exacerbate symptoms,[31] and when necessary is usually limited to one or two days. Prolonged bed rest or inactivity is actually counterproductive, as the resulting stiffness leads to more pain.

- Electrotherapy, such as a Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulator (TENS) has been proposed. Two randomized controlled trials found conflicting results.[32][33] This has led the Cochrane Collaboration to conclude that there is inconsistent evidence to support use of TENS.[34] In addition, spinal cord stimulation, where an electrical device is used to interrupt the pain signals being sent to the brain and has been studied for various underlying causes of back pain.

- Inversion therapy is useful for temporary back relief due to the traction method or spreading of the back vertebres through (in this case) gravity. The patient hangs in an upside down position for a period of time from ankles or knees until this separation occurs. The effect can be achieved without a complete vertical hang ( 90 degree) and noticeable benefits can be observed at angles as low as 10 to 45 degrees.

Clinical Trials

There are many clinical trials sponsored both by industry and the National Institutes of Health. Clinical trials sponsored by the National Institutes of Health related to back pain can be viewed at NIH Clinical Back Pain Trials.

A 2008 randomized controlled trial found marked improvement in addressing back pain with The Alexander Technique. Exercise and a combination of 6 lessons of AT reduced back pain 72% as much as 24 AT lessons. Those receiving 24 lessons had 18 fewer days of back pain than the control median of 21 days.[24]

Pregnancy

About 50% of women experience low back pain during pregnancy.[35] Back pain in pregnancy may be severe enough to cause significant pain and disability and pre-dispose patients to back pain in a following pregnancy. No significant increased risk of back pain with pregnancy has been found with respect to maternal weight gain, exercise, work satisfaction, or pregnancy outcome factors such as birth weight, birth length, and Apgar scores.

Biomechanical factors of pregnancy that are shown to be associated with low back pain of pregnancy include abdominal sagittal and transverse diameter and the depth of lumbar lordosis. Typical factors aggravating the back pain of pregnancy include standing, sitting, forward bending, lifting, and walking. Back pain in pregnancy may also be characterized by pain radiating into the thigh and buttocks, night-time pain severe enough to wake the patient, pain that is increased during the night-time, or pain that is increased during the day-time. The avoidance of high impact, weight-bearing activities and especially those that asymmetrically load the involved structures such as: extensive twisting with lifting, single-leg stance postures, stair climbing, and repetitive motions at or near the end-ranges of back or hip motion can easen the pain. Direct bending to the ground without bending the knee causes severe impact on the lower back in pregnancy and in normal individuals, which leads to strain, especially in the lumbo-saccral region that in turn strains the multifidus.

See also

- Failed back syndrome

- Low back pain

- Posterior Rami Syndrome

- Tension myositis syndrome

- Upper back pain

- Pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain

References

- ↑ A.T. Patel, A.A. Ogle. "Diagnosis and Management of Acute Low Back Pain". American Academy of Family Physicians. Retrieved March 12, 2007.

- ↑ Borenstein DG, O'Mara JW, Boden SD, et al (2001). "The value of magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine to predict low-back pain in asymptomatic subjects : a seven-year follow-up study". The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume 83-A (9): 1306–11. PMID 11568190.

- ↑ Savage RA, Whitehouse GH, Roberts N (1997). "The relationship between the magnetic resonance imaging appearance of the lumbar spine and low back pain, age and occupation in males". European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society 6 (2): 106–14. PMID 9209878.

- ↑ Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS (1994). "Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain". N. Engl. J. Med. 331 (2): 69–73. doi:. PMID 8208267.

- ↑ Kleinstück F, Dvorak J, Mannion AF (2006). "Are "structural abnormalities" on magnetic resonance imaging a contraindication to the successful conservative treatment of chronic nonspecific low back pain?". Spine 31 (19): 2250–7. doi:. PMID 16946663.

- ↑ White AA, Gordon SL (1982). "Synopsis: workshop on idiopathic low-back pain". Spine 7 (2): 141–9. doi:. PMID 6211779.

- ↑ van den Bosch MA, Hollingworth W, Kinmonth AL, Dixon AK (2004). "Evidence against the use of lumbar spine radiography for low back pain". Clinical radiology 59 (1): 69–76. PMID 14697378.

- ↑ Burton AK, Tillotson KM, Main CJ, Hollis S (1995). "Psychosocial predictors of outcome in acute and subchronic low back trouble". Spine 20 (6): 722–8. doi:. PMID 7604349.

- ↑ Carragee EJ, Alamin TF, Miller JL, Carragee JM (2005). "Discographic, MRI and psychosocial determinants of low back pain disability and remission: a prospective study in subjects with benign persistent back pain". The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society 5 (1): 24–35. doi:. PMID 15653082.

- ↑ Hurwitz EL, Morgenstern H, Yu F (2003). "Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations of low-back pain and related disability with psychological distress among patients enrolled in the UCLA Low-Back Pain Study". Journal of clinical epidemiology 56 (5): 463–71. doi:. PMID 12812821.

- ↑ Dionne CE (2005). "Psychological distress confirmed as predictor of long-term back-related functional limitations in primary care settings". Journal of clinical epidemiology 58 (7): 714–8. doi:. PMID 15939223.

- ↑ "At the Root of Back Pain". WholeHealthMD.

- ↑ McGrath, Mike (2004-11-03). "When Back Pain Starts in Your Head: Is repressed anger is causing your back pain?". Prevention.com. Rodale Inc.. Retrieved on 2007-09-12.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 French S, Cameron M, Walker B, Reggars J, Esterman A (2006). "A Cochrane review of superficial heat or cold for low back pain.". Spine 31 (9): 998–1006. doi:. PMID 16641776.

- ↑ van Tulder M, Touray T, Furlan A, Solway S, Bouter L (2003). "Muscle relaxants for non-specific low back pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD004252. doi:. PMID 12804507.

- ↑ van Tulder M, Scholten R, Koes B, Deyo R (2000). "Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD000396. doi:. PMID 10796356.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Nelemans P, de Bie R, de Vet H, Sturmans F (1999). "Injection therapy for subacute and chronic benign low back pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD001824. doi:. PMID 10796449.

- ↑ Friedman B, Holden L, Esses D, Bijur P, Choi H, Solorzano C, Paternoster J, Gallagher E (2006). "Parenteral corticosteroids for Emergency Department patients with non-radicular low back pain". J Emerg Med 31 (4): 365–70. doi:. PMID 17046475.

- ↑ Hayden J, van Tulder M, Malmivaara A, Koes B (2005). "Exercise therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD000335. doi:. PMID 16034851.

- ↑ Malmivaara A, Häkkinen U, Aro T, Heinrichs M, Koskenniemi L, Kuosma E, Lappi S, Paloheimo R, Servo C, Vaaranen V (1995). "The treatment of acute low back pain--bed rest, exercises, or ordinary activity?". N Engl J Med 332 (6): 351–5. doi:. PMID 7823996.

- ↑ Heymans M, van Tulder M, Esmail R, Bombardier C, Koes B (2004). "Back schools for non-specific low-back pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD000261. doi:. PMID 15494995.

- ↑ Furlan A, Brosseau L, Imamura M, Irvin E (2002). "Massage for low back pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD001929. doi:. PMID 12076429.

- ↑ Gard G (2005). "Body awareness therapy for patients with fibromyalgia and chronic pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. PMID 16012065.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Paul Little et al.,Randomised controlled trial of Alexander technique (AT) lessons, exercise, and massage (ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain,British Medical Journal, August 19, 2008.

- ↑ Assendelft W, Morton S, Yu E, Suttorp M, Shekelle P (2004). "Spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD000447. doi:. PMID 14973958.

- ↑ Cherkin D, Sherman K, Deyo R, Shekelle P (2003). "A review of the evidence for the effectiveness, safety, and cost of acupuncture, massage therapy, and spinal manipulation for back pain.". Ann Intern Med 138 (11): 898–906. PMID 12779300.

- ↑ Sarno, John E. (1991). Healing Back Pain: The Mind-Body Connection. Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-39320-8.

- ↑ Ostelo R, van Tulder M, Vlaeyen J, Linton S, Morley S, Assendelft W (2005). "Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD002014. doi:. PMID 15674889.

- ↑ Uceyler N, Sommer C. Cytokine-induced Pain: Basic Science and Clinical Implications. Reviews in Analgesia 2007;9(2):87-103.

- ↑ Yelland M, Mar C, Pirozzo S, Schoene M, Vercoe P (2004). "Prolotherapy injections for chronic low-back pain.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD004059. doi:. PMID 15106234.

- ↑ Hagen K, Hilde G, Jamtvedt G, Winnem M (2004). "Bed rest for acute low-back pain and sciatica.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD001254. doi:. PMID 15495012.

- ↑ Cheing GL, Hui-Chan CW (1999). "Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation: nonparallel antinociceptive effects on chronic clinical pain and acute experimental pain". Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 80 (3): 305–12. doi:. PMID 10084439.

- ↑ Deyo RA, Walsh NE, Martin DC, Schoenfeld LS, Ramamurthy S (1990). "A controlled trial of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and exercise for chronic low back pain". N. Engl. J. Med. 322 (23): 1627–34. PMID 2140432.

- ↑ Khadilkar A, Milne S, Brosseau L, et al (2005). "Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for chronic low-back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD003008. doi:. PMID 16034883.

- ↑ Ostgaard HC, Andersson GBJ, Karlsson K. Prevalence of back pain in pregnancy. Spine 1991;16:549-52.

External links

- Back and spine at the Open Directory Project

- Handout on Health: Back Pain at National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

- Back pain, on Medline plus, a service of the National Library of Medicine

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||