B-58 Hustler

| B-58 Hustler | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Role | Strategic bomber |

| Manufacturer | Convair |

| First flight | 11 November 1956 |

| Introduced | 15 March 1960 |

| Retired | 31 January 1970 |

| Primary user | United States Air Force |

| Number built | 116 |

| Unit cost | US$12.44 million[1] |

The Convair B-58 Hustler was the first operational jet bomber capable of Mach 2 supersonic flight. The aircraft was developed for the United States Air Force for service in the Strategic Air Command (SAC) during the late 1950s. Originally intended to fly at high altitudes and speeds to avoid Soviet fighters, the introduction of highly accurate Soviet surface-to-air missiles forced the B-58 into a low-level penetration role that severely limited its range and strategic value. This led to a brief operational career between 1960 and 1969. Its specialized role would be succeeded by other American supersonic bombers, such as the FB-111A and the later B-1B Lancer.

The B-58 received a great deal of notoriety due to its sonic boom, which was often heard by the public as it passed overhead in supersonic flight.

Contents |

Design and development

The genesis of the B-58 program came in February 1949, when a Generalized Bomber Study (GEBO II) had been issued by the Air Research and Development Command (ARDC) at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio.[2] A number of contractors submitted bids including Boeing, Convair, Curtiss, Douglas, Martin and North American Aviation.

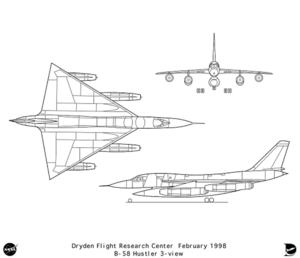

Building on Convair's experience of earlier delta-wing fighters, beginning with the XF-92A, a series of GEBO II designs were developed, initially studying swept and semi-delta configurations, but settling on the delta wing planform. The final Convair proposal, coded FZP-110, was a radical two-place, delta wing bomber design powered by General Electric J53 engines. The performance estimates included a 1,000 mph speed and a 3,000 mile range.[2]

The USAF chose Boeing (MX-1712) and Convair to proceed to a Phase 1 study. The Convair MX-1626 evolved further into a more refined proposal redesignated the MX-1964 that was the winner of the design competition to meet the newly proposed SAB-51 (Supersonic Aircraft Bomber) and SAR-51 (Supersonic Aircraft Reconnaissance), the first General Operational Requirement (GOR) worldwide for supersonic bombers.[2]

The resulting B-58 design was the first "true" USAF supersonic bomber program. The Convair design was based on a delta wing with a leading-edge sweep of 60° with four General Electric J79-GE-1 turbojet engines, capable of flying at twice the speed of sound. Although its large wing made for relatively low wing loading, it proved to be surprisingly well suited for low-altitude, high-speed flight. It seated three (pilot, bombardier/navigator, and defensive systems operator) in separated tandem cockpits. Later versions gave each crew member a novel ejection capsule that made it possible to eject at an altitude of 70,000 ft (21,000 m) at speeds up to Mach 2 (1,320 mph/2,450 km/h). Unlike standard ejection seats of the period, a protective clamshell would enclose the seat and the control stick with an attached oxygen bottle.[3] In an unusual test program, live bears were successfully used to test the ejection system.[4] The XB-70 would use a similar system.

The electronic controls were ambitious and advanced for the day. The pilot cockpit featured minimal gauges and control panels replaced by a wrap around dashboard of warning lights and buttons, and automatic voice messages and warnings from a tape system were audible through the helmet sets. Research during the era of all-male combat aircraft assignments revealed that a woman's voice was more likely to gain the attention of young men in distracting situations. Nortronics Division of Northrop Corporation selected actress and singer Joan Elms to record the automated voice warnings. To the men flying the B-58, the voice was known as "Sexy Sally."[5]

The rear rotary cannon and radar was controlled by the DSO via a cathode ray tube (CRT) display. The navigation system was a huge, sophisticated inertial system[6] and included a star tracker for backup, while the radar controlled bombing system compensated for such things as coriolis effect (earth rotation) during bomb release and trajectory.

Because of heat generated at Mach 2 cruise, not only the crew compartment, but the wheel wells and electronics bay were pressurized and air conditioned. The B-58 utilized one of the first extensive applications of aluminum honeycomb panels, which bonded outer and inner aluminum skins to a honeycomb of aluminum and fiberglass.

The B-58 typically carried a single nuclear weapon in a streamlined MB-1C pod under the fuselage. From 1961 to 1963 it was retrofitted with two tandem stub pylons under each wing, inboard of the engine pod, for B43 or B61 nuclear weapons for a total of five nuclear weapons per airplane. A single 20mm M61 Vulcan cannon was mounted in a radar-directed tail turret for defense, though some would note that at Mach 2, the exit speed of the shells would not be much faster than the speed of the aircraft (essentially relying upon a chasing fighter to fly into the shell, rather than vice-versa). Although the USAF explored the possibility of using the B-58 for the conventional strike role, it was never equipped for carrying or dropping conventional bombs in service. A photo reconnaissance pod, the LA-331, was also fielded. Several other specialized pods for ECM or an early cruise missile were considered, but not adopted.

Operational history

The B-58 crews were elite, hand-picked from other strategic bomber squadrons. Due to some unique aspects of flying a delta-winged aircraft, the pilots used the F-102 Delta Dagger in their transition to the Hustler. The aircraft was difficult to fly and its three-man crews were constantly busy, but the performance of the aircraft was exceptional. A lightly loaded Hustler would climb at nearly 4,600 ft/min (23.5 m/s), comparable to the best contemporary fighter aircraft.[7]

Nevertheless, it had a much smaller weapons load and more limited range than the B-52 Stratofortress. The B-58 had been extremely expensive to acquire (in 1959 it was reported that each of the production B-58As was worth more than its weight in gold). It was a complex aircraft that required considerable maintenance, much of which required specialized equipment and ground personnel, which made it three times as expensive to operate as the B-52. Also against it was an unfavorably high accident rate: 26 B-58 aircraft were lost in accidents, 22.4% of total production. It was very difficult to safely recover from the loss of an engine at supersonic cruise due to differential thrust. SAC had been dubious about the type from the beginning, although its crews eventually became enthusiastic about the aircraft; its performance and design were appreciated, although it was never easy to fly.

During the B-58's active service, only two SAC bomb wings ever operated the aircraft. The first unit was the 43d Bombardment Wing, initially based at Carswell AFB, Texas from 1960 to 1964, followed by Little Rock AFB, Arkansas from 1964 to 1970. The second unit was the 305th Bombardment Wing at Bunker Hill AFB (later Grissom AFB), Indiana from 1961 to 1970. The 305th also operated the B-58 combat crew training school (CCTS), the predecessor of USAF's current formal training units (FTUs).

By the time the early problems had largely been resolved and SAC interest in the bomber had solidified, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara decided that the B-58 was not going to be a viable weapon system. It was during its introduction that the surface-to-air missile became a viable and dangerous weapon system, one the Soviet Union extensively deployed. The "solution" to this problem was to fly at low altitudes, minimizing the radar line-of-sight and thus minimizing detection (exposure) time.

While the Hustler was able to fly these sorts of missions, it could not do so at supersonic speeds, thereby giving up the high performance the design paid so dearly for. Its moderate range suffered further due to the thicker low-altitude air. Its early retirement, slated for 1970, was ordered in 1965, and despite efforts of the Air Force to earn a reprieve, proceeded on schedule. The last B-58s in operational service retired 16 January 1970, largely replaced by the FB-111A, a strategic bomber variant version of the two-seat swing wing fighter that was designed around the low-altitude attack profile, although it was slightly smaller and much less expensive.

A total of 116 B-58s were produced: 30 trial aircraft and 86 production B-58A models. Most of the trial aircraft were later brought up to operational standard. Eight were equipped as TB-58A training aircraft.

A number of B-58s were used for special trials of various kinds, including one (#665 called "Snoopy") used for testing the radar system intended for the Lockheed YF-12 interceptor. Several improved (and usually enlarged) variants, dubbed B-58B and B-58C by the manufacturer, were proposed, but never built.

Variants

- XB-58: Prototype. Two built.

- YB-58A: Pre-production aircraft, 11 built.

- B-58A: Three-seat medium-range strategic bomber aircraft, 86 built.

- TB-58A: Training aircraft, eight conversions from YB-58A.

- NB-58A: This designation was given to a YB-58A, which was used for testing the J93 engine. The engine was originally intended for the XB-70 Valkyrie Mach 3 bomber.

- RB-58A: Variant with ventral reconnaissance pod, 17 built.

- B-58B: Unbuilt version. SAC planned to order 185 of these improved bombers; cancelled due to budgetary considerations.

- B-58C: Unbuilt version. Enlarged version with more fuel and 32,500 lb of thrust J58, the same engine used on the Lockheed SR-71. Design studies were conducted with two and four engine designs, the C model had an estimated top speed approaching Mach 3, a supersonic cruise capability of approximately Mach 2, and a service ceiling of about 70,000 ft along with the capability of carrying conventional bombs. Convair estimated maximum range at 5,200 nautical miles. The B-58C was proposed as a lower cost alternative to the North American XB-70. As enemy defenses against high-speed, high-altitude penetration bombers improved, the value of the B-58C diminished and the program was cancelled in early 1961.[8]

Survivors

Today there are eight B-58 survivors:

- TB-58A, AF Serial No. 55-0663, at the Grissom Air Museum, Peru, Indiana (Oldest Remaining Aircraft... fourth B-58 Built)[9]

- B-58A, AF Serial No. 55-0665 at Edwards Air Force Base,California ("Snoopy")

- B-58A, AF Serial No. 55-0666 the Octave Chanute Aerospace Museum (former Chanute AFB), Rantoul, Illinois

- TB-58A, AF Serial No. 55-0668 Lone Star Flight Museum, Galveston, Texas ("Wild Child II")

- B-58A, AF serial No 59-2437 Lackland AFB/Kelly Field Annex (former Kelly Air Force Base), San Antonio, Texas ("Firefly II")

- B-58A, AF Serial No. 59-2458 National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio ("Cowtown Hustler") This aircraft flew from Los Angeles to New York and back on 5 March, 1962, setting three seperate speed records, and earning the crew the Bendix Trophy and the Mackay Trophy for 1962. The aircraft was flown to the Museum on 1 March, 1969.[10] The aircraft is on display in the Museum's Cold War gallery.

- B-58A, AF Serial No. 61-2059 Strategic Air and Space Museum, Ashland, Nebraska, adjacent to Offutt AFB ("Greased Lightning", which averaged 938 mph flying from Tokyo to London.[11])

- B-58A, AF Serial No. 61-2080 Pima Air & Space Museum, Tucson, Arizona (Last B-58 to be delivered)

Popular culture

- Jimmy Stewart, himself a bomber pilot during the World War II, made a film for the Air Force, flying in the back seat of the B-58 on a typical low-altitude attack in the film Champion of Champions.

- In the 1964 film Fail-Safe, stock footage of B-58s was used to represent the fictional "Vindicator" bombers which attacked Moscow. In Fail Safe, a 2000 made-for-TV remake starring George Clooney, the fictional Vindicator bomber again became a B-58 Hustler.

- Singer John Denver's father, Colonel Henry J. Deutschendorf, Sr., USAF, held several speed records as a B-58 pilot.[12]

Specifications (B-58A)

Data from Quest for Performance[13]

General characteristics

- Crew: 3: pilot; observer (navigator, radar operator, bombardier); defense system operator (DSO; electronic countermeasures operator and pilot assistant).

- Length: 96 ft 9 in (29.5 m)

- Wingspan: 56 ft 9 in (17.3 m)

- Height: 29 ft 11 in (8.9 m)

- Wing area: 1,542 ft² (143.3 m²)

- Airfoil: NACA 0003.46-64.069 root, NACA 0004.08-63 tip

- Empty weight: 55,560 lb (25,200 kg)

- Loaded weight: 67,871 lb (30,786 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 176,890 lb (80,240 kg)

- Powerplant: 4× General Electric J79-GE-5A turbojets, 15,600 lbf (69.3 kN) each

- * Zero-lift drag coefficient: 0.0068

- Drag area: 10.49 ft² (0.97 m²)

- Aspect ratio: 2.09

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 2.1 (1,400 mph, 2,240 km/h) at 40,000 ft (12,000 m)

- Cruise speed: 610 mph (530 knots, 985 km/h)

- Combat radius: 1,740 mi (1,510 nm, 3,220 km)

- Ferry range: 4,720 mi (4,100 nm, 7,590 km)

- Service ceiling 63,400 ft (19,300 m)

- Rate of climb: 2,700 ft/min (13.7 m/s)

- Wing loading: 44.01 lb/ft² (214.9 kg/m²)

- Thrust/weight: 0.919

- Lift-to-drag ratio: 11.3 (without weapons/fuel pod)

Armament

- Guns: 1× 20 mm (0.787 in) T171 cannon

- Bombs: 4× B-43 or B61 nuclear bombs; maximum weapons load was 19,450 lb (8,823 kg)

See also

Comparable aircraft

- A-5 Vigilante

- Avro Vulcan

- BAC TSR-2

- Boeing XB-59

- Dassault Mirage IV

- Tupolev Tu-22 'Blinder'

- Myasishchev M-50

Related lists

- List of bomber aircraft

- List of military aircraft of the United States

References

Notes

- ↑ Knaack, Marcelle Size. Post-World War II bombers, 1945-1973. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1988. ISBN 0-16-002260-6.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Miller 1976, p. 24.

- ↑ On display at the Wings Over the Rockies Air and Space Museum.

- ↑ Vectorsite B-58 Hustler

- ↑ "Sexy Sally Sounds Off." San Francisco Examiner 30 July 1966, reprinted in United States Naval Institute Proceedings, November 1966.

- ↑ Goebel, Greg. The General Dynamics B-58 Hustler. webpage v1.1.0/01 nov 01/public domain. Retrieved: 11 July 2008.

- ↑ Higham et al 1975

- ↑ "Convair B-58C Hustler." National Museum of the USAF. Retrieved: 5 September 2007.

- ↑ TB-58A Hustler Grissom Air Museum. Retrieved: 5 September 2007.

- ↑ United States Air Force Museum 1975, p. 74.

- ↑ Air Force Association. Retrieved: 11 July 2008.

- ↑ Tope, Jessica. "Pope Air Force Base Record Breaking Day." | Pope Air Force Base, 12 January 2007. Retrieved: 5 September 2007.

- ↑ Loftin, Laurence K. Jr. Quest for Performance: The Evolution of Modern Aircraft. NASA SP-468. Retrieved: 4 April 2006.

Bibliography

- Donald, David and Jon Lake, eds. Encyclopedia of World Military Aircraft. London: AIRtime Publishing, 1996. ISBN 1-880588-24-2.

- Gunston, Bill. Bombers of the West. London: Ian Allan Ltd., 1973, pp. 185–213. ISBN 0-7110-0456-0.

- Higham, Robin, Carol Williams and Abigail Siddall, eds. Flying Combat Aircraft of the USAAF-USAF (Vol.1). Andrews AFB, Maryland: Air Force Historical Foundation, 1975. ISBN 0-8138-0325-X.

- Miller, Jay. "History of the Hustler." Airpower, Vol. 6, No. 4, July 1976.

- Swanborough, Gordon and Peter M. Bowers. United States Military Aircraft Since 1909. Washington, DC: Smithsonian, 1989. ISBN 0-87474-880-1.

- United States Air Force Museum. Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio: Air Force Museum Foundation. 1975.

- Wagner, Ray. American Combat Planes of the Twentieth Century. Reno, Nevada: Jack Bacon and Co., 2004. ISBN 0-930083-17-2.

- Winchester, Jim, ed. "Convair B-58 Hustler." Military Aircraft of the Cold War (The Aviation Factfile). Rochester, Kent, UK: The Grange plc., 2006. ISBN 1-84013-929-7.

External links

- BJ Brown's Hustler Hangar

- Hustler House

- B-58.com - The B-58 Hustler Page

- Aerospaceweb.org profile of the B-58

- Convair B-58 Hustler Rendezvous

- Aviation-history.com profile of the B-58

- * Video of B-58 operations from Military.com

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||