B-17 Flying Fortress

| B-17 Flying Fortress | |

|---|---|

|

|

| This TB-17G was assigned various USAAF training commands | |

| Role | Strategic bomber |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Boeing |

| First flight | 28 July 1935[1] |

| Introduction | April 1938 |

| Retired | 1968 (Brazilian Air Force) |

| Primary users | United States Army Air Force Royal Air Force |

| Produced | 1936–1945 |

| Number built | 12,731[2] |

| Unit cost | US$238,329[3] |

| Variants | XB-38 Flying Fortress YB-40 Flying Fortress C-108 Flying Fortress Boeing 307 |

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is a four-engine heavy bomber aircraft developed for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). Competing against Douglas and Martin for a contract to build 200 bombers, the Boeing entry outperformed both the other competitors and more than met the Air Corps' expectations. Although Boeing lost the contract due to the prototype's crash, the Air Corps was so impressed with Boeing's design that they ordered 13 B-17s. The B-17 Flying Fortress went on to enter full-scale production and was considered the first truly mass-produced large aircraft, eventually evolving through numerous design advancements.

The B-17 was primarily employed by the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) in the daylight precision strategic bombing campaign of World War II against German industrial, civilian and military targets. The United States Eighth Air Force based in England and the Fifteenth Air Force based in Italy complemented the RAF Bomber Command's nighttime area bombing in Operation Pointblank, to help secure air superiority over the cities, factories and battlefields of Western Europe in preparation for Operation Overlord.[4] The B-17 also participated, to a lesser extent, in the War in the Pacific, where it conducted raids against Japanese shipping.

From its pre-war inception, the USAAC (later USAAF) touted the aircraft as a strategic weapon; it was a potent, high-flying, long-ranging bomber capable of unleashing great destruction yet able to defend itself. With the ability to return home despite extensive battle damage, its durability, especially in belly-landings and ditchings, quickly took on mythic proportions.[5][6][7] Stories and photos of B-17s surviving battle damage widely circulated, increasing its iconic status.[8] Despite an inferior range and bombload compared to the more numerous B-24 Liberator,[9] a survey of Eighth Air Force crews showed a much higher rate of satisfaction in the B-17.[10] With a service ceiling greater than any of its Allied contemporaries, the B-17 established itself as a superb weapons system, dropping more bombs than any other U.S. aircraft in World War II. Of the 1.5 million tonnes of bombs dropped on Germany by U.S. aircraft, 640,000 were dropped from B-17s [11].

Contents |

Design and development

On 8 August 1934, the U.S. Army Air Corps (USAAC) tendered a proposal for a four-engined bomber to replace the Martin B-10. Requirements were that it would carry a "useful bombload" at an altitude of 10,000 ft (3 km) for ten hours with a top speed of at least 200 mph (320 km/h).[12][13] They also desired, but did not require, a range of 2,000 miles (3200 km) and a speed of 250 mph (400 km/h). The Air Corps were looking for a bomber capable of reinforcing the air forces in Hawaii, Panama, and Alaska.[14] The competition would be decided by a "fly-off" at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio. Boeing competed with the Douglas DB-1 and Martin Model 146 for the Air Corps contract.

The prototype B-17, designated Model 299, was designed by a team of engineers led by E. Gifford Emery and Edward Curtis Wells and built at Boeing's own expense.[13] It combined features of the experimental Boeing XB-15 bomber with the Boeing 247 transport airplane.[12] The B-17 was armed with bombs (up to 4,800 pounds (2200 kg) on two racks in the bomb bay behind the cockpit) and five 0.30 inch (7.62 mm) caliber machine guns, and was powered by Pratt & Whitney R-1690 radial engines each producing 750 horsepower (600 kW) at 7,000 ft (2100 m).[13]

The first flight of the Model 299 was on 28 July 1935, with Boeing chief test-pilot Les Tower at the controls.[15][1] Richard Williams, a reporter for the Seattle Times coined the name "Flying Fortress" when the Model 299 was rolled out, bristling with multiple machine gun installations.[16] Boeing was quick to see the value of the name and had it trademarked for use. On 20 August, the prototype flew from Seattle to Wright Field in nine hours and three minutes at an average speed of 235 mph (378 km/h), much faster than the competition.[13]

At the fly-off, the four-engine Boeing design displayed superior performance over the twin-engine DB-1 and Model 146, and then-Major General Frank Maxwell Andrews of the GHQ Air Force believed that the long-range capabilities of four-engine large aircraft were more efficient than shorter-ranged twin-engined airplanes. His opinions were shared by the Air Corps procurement officers and, even before the competition was finished, they suggested buying 65 B-17s.[17]

Development continued on the Boeing Model 299, and on 30 October 1935, the Army Air Corps test-pilot, Major Ployer Peter Hill and Boeing employee Les Tower, took the Model 299 on a second evaluation flight. The crew forgot to disengage the airplane's "gust lock," a device that held the bomber's movable control surfaces in place while the plane was parked on the ground, and having taken off, the aircraft entered a steep climb, stalled, nosed over and crashed, killing Hill and Tower (other observers survived with injuries).[18][19] The crashed Model 299 could not finish the evaluation, and while the Air Corps was still enthusiastic about the aircraft's potential, Army officials were daunted by the much greater expense per aircraft. [20][21] "The loss was not total, however, since the fuselage aft of the wing was intact, and the Wright Field Armament section was able to use it in subsequent gun mount development work, but Boeing's hopes for a substantial bomber contract were dashed."[22] Army Chief of Staff Malin Craig cancelled the order for 67 B-17s, and ordered 133 of the twin-engine Douglas B-18 Bolo instead.[17][13]

Regardless, the USAAC had been impressed by the prototype's performance and, on 17 January 1936, the Air Corps ordered, through a legal loophole,[23] 13 YB-17s for service testing. The YB-17 incorporated a number of significant changes from the Model 299, including more powerful Wright R-1820-39 Cyclone engines replacing the original Pratt & Whitneys. Although the prototype was company owned and never received a military serial ("the B-17 designation itself did not appear officially until January 1936, nearly three months after the prototype crashed"),[22] the term "XB-17" was retroactively applied to the airframe and has entered the lexicon to describe the first Flying Fortress.

On 1 March 1937, 12 of the 13 YB-17s were delivered to the 2nd Bombardment Group at Langley Field in Virginia, and used to help develop heavy bomber techniques and work out other bugs.[12] One suggestion was the use of a checklist, to avoid accidents such as the Model 299's.[24][23] In one of their first missions, three B-17s, following lead navigator Lt. Curtis LeMay, were sent by General Andrews to "intercept" the Italian ocean liner Rex 800 statute miles (1,300 km) off the Atlantic coast and take photographs. The successful mission was widely publicized.[25][26]. The 13th YB-17 was delivered to the Material Division at Wright Field, Ohio, to be used for flight testing.[27]

A 14th YB-17 (37-369), originally constructed for ground testing of the airframe's strength, was upgraded and fitted with exhaust-driven turbochargers. Scheduled to fly in 1937, it encountered problems with the turbochargers and its first flight was delayed until 29 April 1938.[28] Modifications cost Boeing US$100,000 and took until spring 1939 to complete, but resulted in an increased service ceiling and maximum speed.[29] The aircraft was delivered to the Army on 31 January 1939 and was redesignated B-17A to signify the first operational variant.[30]

In late 1937, the Air Corps ordered ten more aircraft, designated B-17B and, soon after, another 29.[29] Improved with larger flaps, rudder and Plexiglas nose, the B-17Bs were delivered between July 1939 and March 1940. They equipped two bombardment groups, one on each U.S. coast.[31][32]

Prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor, fewer than 200 B-17s were in service with the Army,[23] but production quickly accelerated, and the B-17 became the first truly mass-produced large aircraft.[33][34] The aircraft went on to serve in every World War II combat zone, and by the time production ended in May 1945, 12,731 aircraft had been built by Boeing, Douglas and Vega (a subsidiary of Lockheed).[35]

Operational history

The B-17 began operations in World War II with the RAF in 1941, USAAF Eighth Air Force and Fifteenth Air Force units in 1942, and was primarily involved in the daylight precision strategic bombing campaign against German industrial targets. Operation Pointblank guided attacks in preparation for a ground assault.[4]

During World War II, the B-17 equipped 32 overseas combat groups, inventory peaking in August 1944 at 4,574 USAAF aircraft worldwide,[36] and dropped 640,036 long tons (650,195 tonnes) of bombs on European targets (compared to 452,508 tons (451,691 tonnes) dropped by the Liberator and 463,544 tons (420,520 tonnes) dropped by all other U.S. aircraft). Approximately 4,750, or one third, of B-17s built were lost in combat.[9]

The RAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) entered World War II with no heavy bomber of its own and while by 1941, the Short Stirling and Handley Page Halifax had become its primary bombers, in early 1940, the RAF entered into an agreement with the U.S. Army Air Corps to be provided with 20 B-17Cs, redesignated Fortress I. Their first operation was against Wilhelmshaven on 8 July 1941.[37][31][38] At the time, the Air Corps considered high-altitude flight to be 20,000 ft (6 km) but, to avoid being intercepted by fighter aircraft, the RAF bombed the naval barracks from 30,000 ft (9 km).[39] They were unable to hit their targets and temperatures were so low that the machine guns froze up.[40] On 24 July, they tried another target, Brest in France, but again missed completely.

ex-B-17C BO AAF S/N 40-2065

soc: 8 Nov 1941 North Africa.

By September, after the RAF had lost eight B-17Cs in combat or to accidents, Bomber Command had abandoned daylight bombing raids due to the Fortress I's poor performance. The remaining aircraft were transferred to different commands for deployment to various duties including coastal defence.[40] The experience had showed both the RAF and USAAF that the B-17C was not ready for combat, and that improved defenses, larger bomb loads and more accurate bombing methods were required, which would be incorporated in later versions. Moreover, even with these improvements, it was the USAAF and not the RAF that was willing to remain faithful to using the B-17 as a "day" bomber.[39]

Bomber Command transferred its remaining Fortress I aircraft to Coastal Command for use as very long range patrol aircraft. These were later augmented in August 1942 by 19 Fortress Mk II and 45 Fortress Mk IIA (B-17F and B-17E, respectively — the USAAF offered the B-17F before offering the B-17E, thus the apparently reversed designations).[41] A Fortress from No. 206 Squadron RAF sank U-627 on 27 October 1942: the first of 11 U-boat kills credited to RAF Fortress bombers during the war.[42]

The USAAF

The Air Corps (renamed United States Army Air Forces or USAAF in 1941), utilizing the B-17 and other bombers, bombed from high altitudes using the then-secret Norden Bombsight, which was an optical electro-mechanical gyro-stabilized computer. During daylight bombing missions and sorties, the device was able to determine, from variables input by the bombardier, the point in space at which the bomber's ordnance type should be released to hit the target. The bombardier essentially took over flight control of the aircraft during the bomb run, maintaining a level attitude during the final moments.[43]

The USAAF began building up its air forces in Europe using B-17Es soon after entering the war. The first Eighth Air Force units arrived in High Wycombe, England on 12 May 1942, to form the 97th Bomb Group.[12] On 17 August 1942, 18 B-17Es of the 97th, including Yankee Doodle, flown by Major Paul Tibbets and Brigadier General Ira Eaker, were escorted by RAF Spitfires on the first USAAF raid over Europe, against railroad marshalling yards at Rouen-Sotteville in France.[44][12] The operation was a success, with only minor damage to two aircraft.

Combined offensive

The two different strategies of the American and British Bomber commands were organized at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943. The resulting Operation Pointblank described a "Combined Bomber Offensive" that would weaken the Wehrmacht and establish air superiority in preparation of a ground offensive.[4]

Operation Pointblank opened with attacks on targets in Western Europe. General Ira C. Eaker and the Eighth Air Force placed highest priority on attacks on the German aircraft industry, especially fighter assembly plants, engine factories and ball-bearing manufacturers.[4]

On 17 April 1943, an attack on the Focke-Wulf plant at Bremen by 115 Fortresses met with little success. Sixteen aircraft were shot down, and 48 others were damaged.[45] The attacks did succeed, however, in diverting about half the Luftwaffe's fighter force to anti-bomber operations.

Since the airfield bombings were not appreciably reducing German fighter strength, additional B-17 groups were formed, Eaker ordered major missions deeper into Germany against important industrial targets. The 8th Air Force then targeted the ball-bearing factories in Schweinfurt, hoping to cripple the war effort there. The first raid on 17 August 1943 did not result in critical damage to the factories, with the 230 attacking B-17s being intercepted by an estimated 300 Luftwaffe fighters. Thirty-six aircraft were shot down with the loss of 200 men, and coupled with a raid earlier in the day against Regensburg, a total of 60 B-17s were lost that day.

A second attempt on 14 October 1943 would later come to be known as "Black Thursday".[46] Of the 291 attacking Fortresses, 59 were shot down over Germany, one ditched in the English Channel, five crashed in England, and 12 more were scrapped due to battle damage or crash-landings (more by AA guns than the Luftwaffe), a total loss of 77 B-17s. One hundred and twenty-two bombers were damaged to some degree and needed repairs before their next flight. Out of 2,900 men in the crews, about 650 men did not return, although some survived as POWs. Five were killed and 43 wounded in the damaged aircraft that made it home, and 594 were listed as Missing in Action. Only 33 bombers landed without damage.

These losses of air crews could not be sustained, and the USAAF, recognizing the vulnerability of heavy bombers against interceptors, suspended daylight bomber raids deep into Germany until the development of an escort fighter that could protect the bombers all the way from the United Kingdom to Germany and back. The Eighth Air Force alone lost 176 bombers in October 1943.[47] The Eighth Air Force was to suffer similar casualties on 11 January 1944 on missions to Oschersleben, Halberstadt and Brunswick. Doolittle had ordered the mission to be cancelled as the weather deteriorated, but the lead units had already entered hostile air space and continued with the mission. Most of the escorts turned back or missed the rendezvous, as a result 60 B-17s were destroyed[48][49] A third raid on Schweinfurt on 24 February 1944 highlighted what came to be known as "Big Week". With P-51 Mustang and P-47 Thunderbolt fighters (equipped with improved drop tanks to extend their range) escorting the American heavies all the way to and from the targets, only 11 of 231 B-17s were lost.[50] The escort fighters reduced the loss rate to below seven percent, with only 247 B-17s lost in 3500 sorties while taking part in the Big Week raids.[51]

By September 1944, 27 of the 40 bomb groups of the Eighth Air Force and six of the 21 groups of the Fifteenth Air Force utilized B-17s. Losses to flak continued to take a high toll of heavy bombers through 1944, but by 27 April 1945, (two days after the last heavy bombing mission in Europe) the rate of aircraft loss was so low that replacement aircraft were no longer arriving and the number of bombers per bomb group was reduced. The Combined Bomber Offensive was effectively complete.[52]

Pacific Theater

Only five B-17 groups operated in the Southwest Pacific theater, and all converted to other types in 1943.

On 7 December 1941, a group of a dozen B-17s of the 38th (four B-17C) and 88th (eight B-17E) Reconnaissance Squadrons, en route to reinforce the Philippines, were flown into Pearl Harbor from Hamilton Field, California, arriving during the Japanese attack. Leonard "Smitty" Smith Humiston, co-pilot on 1st Lt Robert H. Richards' B-17C, AAF S/N 40-2049, reported that he thought the U.S. Navy was giving the flight a 21 gun salute to celebrate the arrival of the bombers, after which he realized that Pearl Harbor was under attack. The Fortress came under fire from Japanese fighter aircraft, though the crew was unharmed with the exception of one who suffered an abrasion on his hand. Enemy activity forced an abort from Hickam Field to Bellows Field, where the aircraft overran the runway and into a ditch where it was then strafed. Although initially deemed repairable, 40-2049 (11th BG / 38th RS) suffered more than 200 bullet holes and never flew again. Ten of the twelve Fortresses survived the attack.[54]

By 1941, the Far East Air Force (FEAF) based at Clark Field in the Philippines had 35 B-17s, with the War Department eventually planning to raise that to 165. When the FEAF received word of the attack on Pearl Harbor, General Lewis H. Brereton sent his bombers and fighters on various patrol missions to prevent them from being caught on the ground. Brereton planned B-17 raids on Japanese air fields in Formosa, in accordance with Rainbow 5 war plan directives, but this was overruled by General Douglas MacArthur. A series of disputed discussions and decisions, followed by several confusing and false reports of air attacks, delayed the authorization of the sortie. By the time that the B-17s and escorting Curtiss P-40 fighters were about to get airborne, they were destroyed by Japanese bombers of the 11th Air Fleet. The FEAF lost fully half its aircraft during the first strike, and was all but destroyed over the next few days.

Typhoon McGoon II of the 11th BG / 98th BS, taken in January 1943 in New Caledonia. Note the antennas mounted above the nose plexiglass used for radar tracking of surface vessels.

Another early World War II Pacific engagement on 10 December 1941 involved Colin Kelly who reportedly crashed his B-17 into the Japanese battleship Haruna, which was later acknowledged as a near bomb miss on the light cruiser Ashigara. Nonetheless, this deed made him a celebrated war hero. Kelly's B-17C AAF S/N 40-2045 (19th BG / 30th BS) crashed about six miles (10 km) from Clark Field after he held the burning Fortress steady long enough for the surviving crew to bail out. Kelly was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.[55] Noted Japanese ace Saburo Sakai is credited with this kill, and in the process, gained respect for the ability of the Fortress to absorb punishment.[56]

B-17s were used in early battles of the Pacific with little success, notably the Battle of Coral Sea and Battle of Midway. While there, the Fifth Air Force B-17s were tasked with disrupting the Japanese sea lanes. Air Corps doctrine dictated bombing runs from high altitude, but it was soon discovered that only one percent of their bombs hit targets. However, B-17s were operating at heights too great for most A6M Zero fighters to reach, and the B-17's heavy gun armament was easily more than a match for lightly protected Japanese planes.

On March 2, 1943, six B-17s of the 64th Squadron attacked a major Japanese troop convoy from 10,000 ft (3 km) during the early stages of the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, off New Guinea, using skip bombing to sink three merchant ships including the Kyokusei Maru. A B-17 was shot down by a New Britain-based A6M Zero, whose pilot then machine-gunned some of the B-17 crew members as they descended in parachutes and attacked others in the water after they landed.[57] Later, 13 B-17s bombed the convoy from medium altitude, causing the ships to disperse and prolonging the journey. The convoy was subsequently all but destroyed by a combination of low level strafing runs by Royal Australian Air Force Beaufighters, and skip bombing by USAAF B-25 Mitchells at 100 ft (30 m), while B-17s claimed five hits from higher altitudes.[58]

A peak of 168 B-17 bombers were in theater in September 1942, with all groups converting to other types by mid-1943.

Bomber defense

Before the advent of long-range fighter escorts, B-17s had only their .50 in (12.7 mm) caliber M2 Browning machine guns to rely on for defense during the bombing runs over Europe. As the war intensified, Boeing used feedback from aircrews to improve each new variant with increased armament and armor.[59] The number of defensive guns increased from four 0.50 (12.7 mm) inch machine guns and one 0.30 inch (7.62 mm) nose machine gun in the B-17C, to 13 0.50 inch (12.7 mm) machine guns in the B-17G. But because the bombers could not maneuver when attacked by fighters, and during their final bomb run they needed to be flown straight and level, individual aircraft struggled to fend off a direct attack.

A 1943 survey by the Air Corps found that over half the bombers shot down by the Germans had left the protection of the main formation.[60] To address this problem, the United States developed the bomb-group formation, which evolved into the staggered combat box formation where all the B-17s could safely cover any others in their formation with their machine guns, making a formation of the bombers a dangerous target to engage by enemy fighters.[61][45] Luftwaffe "Jagdflieger" (fighter pilots) likened attacking a B-17 combat box formation to encountering a fliegendes Stachelschwein, or "flying porcupine". However, the use of this rigid formation meant that individual aircraft could not engage in evasive manoeuvres: they had to always fly in a straight line, which made them vulnerable to the German 88 mm anti-aircraft gun. Additionally, German fighter aircraft later used the tactic of high-speed strafing passes rather than engaging with individual aircraft to inflict maximum damage with minimum risk.

As a result, the B-17s' loss rate was up to 25% on some early missions (60 of 291 B-17s were lost in combat on the second Raid on Schweinfurt[62]), and it was not until the advent of effective long-range fighter escorts (particularly the P-51 Mustang)— resulting in the degradation of the Luftwaffe as an effective interceptor force between February and June 1944 — that the B-17 became strategically potent.

The B-17 was noted for its ability to absorb battle damage, still reach its target and bring its crew home safely. Wally Hoffman, a B-17 pilot with the Eighth Air Force during World War II, said, "The plane can be cut and slashed almost to pieces by enemy fire and bring its crew home."[63] Martin Caidin reported one instance in which a B-17 suffered a midair collision with a Focke-Wulf 190, losing an engine and suffering serious damage to both the starboard horizontal stabilizer and the vertical stabilizer, and being knocked out of formation by the impact. The airplane was reported as shot down by observers, but it survived and brought its crew home without injury.[64] Its toughness more than compensated for its shorter range and lighter bomb load when compared to the Consolidated B-24 Liberator or the British Avro Lancaster heavy bombers. Stories abound of B-17s returning to base with tails having been destroyed, with only a single engine functioning or even with large portions of wings having been damaged by flak.[65] This durability, together with the large operational numbers in the Eighth Air Force and the fame achieved by the "Memphis Belle", made the B-17 a significant bomber aircraft of the war.

The B-17 design went through eight major changes over the course of its production, culminating in the B-17G, differing from its immediate predecessor by the addition of a chin turret with two .50 inch (12.7 mm) caliber M2 Browning machine guns under the nose. This eliminated the B-17's main defensive weakness in head-on attacks.

The Luftwaffe

After examining wrecked B-17s and B-24s, Luftwaffe officers discovered that at least 20 hits with 20 mm shells fired from the rear could bring them down. Pilots of average ability hit the bombers with only about two percent of the rounds they fired, so to obtain 20 hits, the average pilot had to aim one thousand 20 mm rounds at the bomber. Early versions of the Fw 190, one of the best German interceptor fighters, were equipped with two 20 mm MG FF cannons, which carried only 500 rounds, and later with the better Mauser MG 151/20 cannons, which had a longer effective range than the MG FF weapon. The fighter's firing range, 400 meters, was also shorter than the B-17's 1,000 meters, and so was vulnerable while closing in through that distance. The German fighters found that when attacking from the front, where fewer defensive guns were pointed, it only took four or five hits to bring a bomber down.[66] To address the Fw 190's shortcomings, the number of cannons fitted was doubled to four with a corresponding increase in the amount of ammunition carried, and in 1944, a further upgrade to 30 mm MK 108 cannons was made, which could bring a bomber down in just a few hits.

The adoption by the Luftwaffe in mid-August 1943, as a "stand-off" style of offense, of the Werfer-Granate 21 (Wfr.Gr. 21) Dodel rocket mortar, with one strut-mounted tubular launcher fixed under each wing panel on the Luftwaffe's single engined fighters, and two under each wing panel on a few Bf 110 daylight Zerstörer aircraft, had the promise of being a major weapon, but due to the ballistic drop of the fired rocket, even with the usual strut mounting of the launcher fixing it in about a 15° upward orientation, and the low numbers of fighters fitted with the Dodel weapons, the Wfr.Gr. 21 never had a major effect on the combat box fomations of Fortresses. Also, the attempts of the Luftwaffe to fit heavy-calibre Bordkanone-series 37, 50 and even 75 mm cannon on twin engined aircraft such as the special Ju 88P fighters, and even on one model of the Me 410 Hornisse, as anti-bomber weapons did not have much effect on the American strategic bomber offensive. The Me 262 had moderate success against the B-17 late in the war. Equipped with the R4M rocket, it could fire from outside the range of the bombers' .50 caliber defensive guns and bring an aircraft down with one hit.[67]

During World War II, after crash-landing or being forced down, approximately 40 B-17s were captured and refurbished by the Luftwaffe with about a dozen put back into the air. Given German markings and codenamed "Dornier Do 200",[68] the captured B-17s were used for clandestine spy and reconnaissance missions by the Luftwaffe — most often used by the Luftwaffe unit known as Kampfgeschwader 200.[68] One of the B-17s of KG200, bearing Luftwaffe markings A3+FB, was interned by Spain when it landed at Valencia airport, 27 June 1944, and remained there for the rest of the war. Some B-17s kept their Allied markings and were used in attempts to infiltrate B-17 formations and report on their position and altitude. The practice was initially successful, but the Army Air Force combat aircrews quickly developed and established standard procedures to first warn off, and then fire upon any "stranger" trying to join a group's formation.[12] Still other B-17s were used to determine the airplane's vulnerabilities and to train German interceptor pilots in tactics.[69] Few surviving aircraft were found by the Allies following the war.

Postwar history

U.S. Air Force

Following World War II, the B-17 was declared obsolete and the Army Air Force retired most of its fleet. Flight crews ferried the bombers back across the Atlantic to the United States, where the majority were sold for scrap and melted down. Following its establishment as an independent service in 1947, the United States Air Force had B-17 Flying Fortresses (called F-9s: for Fotorecon, at first, later RB-17s) in service with the Strategic Air Command (SAC) from 1946 through 1951. The USAF Air Rescue Service of the Military Air Transport Service (MATS) also operated SB-17s as open ocean search and rescue aircraft during the late 1940s and early to mid-1950s.

By the late 1950s, the last B-17s in operational USAF service were QB-17 target drones, DB-17P drone controllers, and a few VB-17 executive transport aircraft. The last operational mission flown by a USAF Fortress was conducted on 6 August 1959, when DB-17P 44-83684 directed QB-17G 44-83717 out of Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico as a target for a Falcon air-to-air missile fired from an F-101 Voodoo. A retirement ceremony was held several days later at Holloman, after which 44-83684 was retired to the Military Aircraft Storage and Disposition Center (MASDC) at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona.

During the last year of the war and shortly thereafter, the U.S. Navy acquired 48 ex-USAAF B-17s for patrol and air-sea rescue work. At first, these planes operated under their original USAAF designations, but on July 31, 1945 they were assigned the naval aircraft designation PB-1, a designation which had originally been used in 1925 for an experimental flying boat. Since most of the Fortresses involved were actually built by Douglas or Lockheed and not by Boeing, a more logical designation would have been P4D-1W or P3V-1G respectively.

The Navy Bureau of Aeronautics assigned the sequence of Navy/Marine Corps Bureau Numbers (BUNOs) between 77225 and 77258 to these aircraft. Later, two additional sequences were set aside--82855/82857 and 83992/84027.

Twenty-four B-17Gs (including one B-17F that had been modified to G standards) were used by the Navy under the designation PB-1W. The W stood for antisubmarine warfare. A large radome for an AN/APS-20 search radar was fitted underneath the fuselage and additional internal fuel tanks were added for longer range. These planes were painted dark blue, a standard Navy paint scheme which had been adopted in late 1944. Most of these planes were Douglas-built aircraft, flown directly from the Long Beach factory to the Naval Aircraft Modification Unit at NAS Johnsville/NAS Warminster, Pennsylvania during the summer of 1945, where the APS-20 search radar was fitted. However, the war ended before any PB-1Ws could be deployed and the defensive armament was subsequently deleted.

The first few PB-1Ws went to Patrol Bomber Squadron 101 (VPB-101) in April 1946. The PB-1W eventually evolved into an early warning aircraft by virtue of its APS-20 search radar. By 1947, PB-1Ws had been deployed to units operating with both the Atlantic and Pacific fleets. VPB-101 on the East Coast was redesignated Air Test and Evaluation Squadron FOUR (VX-4) and assigned to NAS Quonset Point, Rhode Island. VX-4 later became Airborne Early Warning Squadron TWO (VW-2) in 1952 and transferred to NAS Patuxent River, Maryland. VW-2's primary mission was early warning, with secondary missions of antisubmarine warfare and hurricane reconnaissance. Airborne Early Warning Squadron ONE (VW-1) was established in 1952 with four PB-1Ws at NAS Barbers Point, Hawaii. with elements drawn from Fleet Composite Squadron ELEVEN (VC-11} at NAS Miramar and Patrol Squadron 51 (VP-51) at NAS North Island in San Diego. VW-1's mission set was similar to that of VW-2.

PB-1Ws continued in USN service until 1955, gradually being phased out in favor of the Lockheed WV-2 (known in the USAF as the EC-121), a military version of the Lockheed 1049 Constellation commercial airliner. PB-1Ws were retired to the Naval Aircraft Storage Center at NAS Litchfield Park, Arizona and were stricken from inventory in mid-1956. Many were sold as surplus and ended up on the civil aircraft register and 13 were sold as scrap.

Two ex-USAAF B-17s were obtained by the Navy under the designation XPB-1 for various development programs. The first was transferred to the Navy in June 1945, and the second was transferred in August 1946. The second plane was used by the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory in a jet engine test program and was stricken in 1955.

In May 1947, six additional B-17Gs of unknown serial numbers were transferred to the Navy and assigned BuNos 83993 to 83998. They were stored at NAS Corpus Christi, Texas until August 31, 1947, when they were stricken after no apparent use.

Two additional PB-1s were transferred to the Navy in 1950, these planes coming from the Air Force, which had modified two EB-17Gs to PB-1W configuration for test programs. After the completion of these tests, these planes were transferred to the Navy and assigned BUNO 77137 and BUNO 77138, which was unusual in that these Bureau Numbers had originally been set aside as part of a block of PB4Y aircraft.

Seventeen ex-USAAF Vega-built B-17Gs were used by the U.S. Coast Guard under the designation PB-1G. In July 1945, 18 B-17s were set aside by the USAAF for transfer to the Coast Guard via the Navy. These aircraft were initially assigned Navy Bureau Numbers and the first PB-1Gs were delivered to the Coast Guard beginning in July 1946. Only fifteen PB-1Gs were actually transferred to the Coast Guard, and they carried Navy Bureau Numbers between 77246 and 77257, plus 82855 and 82856 from the second serial block. The USCG obtained one more aircraft directly from the USAF in 1947. It never received a Navy BuNo or a USCG aircraft serial number, serving with a truncated version of its original USAAF/USAF serial (85832).

Coast Guard PB-1Gs were stationed throughout the hemisphere, with five at Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City, North Carolina, two at CGAS San Francisco, two at NAS Argentia, Newfoundland, one at CGAS Kodiak, Alaska, and one in Washington state. They were used primarily for air-sea rescue, but were also used for iceberg patrol duties and for photo mapping. Air-sea rescue PB-1Gs usually carried a droppable lifeboat underneath the fuselage and were painted in yellow and black air-rescue markings. The chin turret was often replaced by a radome. In postwar years, Coast Guard PB-1Gs would often carry the national insignia on their vertical tails rather than on the fuselage, a practice that continues on U.S. Coast Guard fixed-wing aircraft to this day. The Coast Guard PB-1Gs served throughout the 1950s, the last example (AAF Ser. No. / AF Ser. No. 44-85828, BuNo 77254) not being withdrawn from service until October 14, 1959. This airplane was sold as surplus, operated as an air tanker for many years, and is now on display in Arizona.[70]

Other Uses

About a dozen B-17s are still operable of some 50 airframes known to survive. Many of these surviving examples are surplus or training aircraft, which stayed in the U.S. during World War II. However, there are a few exceptions.

Several B-17s, along with other World War II bombers, were converted into airliners or corporate aircraft. Other B-17s saw extended and valiant service, either as aerial spray aircraft against fire ant infestations in the southeastern United States or as converted aerial tankers used for fighting forest fires in the western United States.[71]

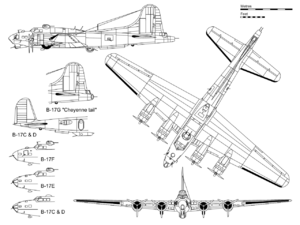

Variants/design stages

| Variant | Produced | First flight |

|---|---|---|

| Model 299 | 1 | 28 July 1935[1] |

| YB-17 | 13 | 2 December 1936[72] |

| YB-17A | 1 | 29 April 1938.[28] |

| B-17B | 39 | 27 June 1939[43] |

| B-17C | 38 | 21 July 1940[73] |

| B-17D | 42 | 3 February 1941[74] |

| B-17E | 512 | 5 September 1941[75] |

| B-17F | 3,405 | 30 May 1942[76] |

| B-17F-BO | 2,300 | |

| B-17F-DL | 605 | |

| B-17F-VE | 500 | |

| B-17G | 8,680 | |

| B-17G-BO | 4,035 | |

| B-17G-DL | 2,395 | |

| B-17G-VE | 2,250 | |

| Grand total | 12,731 |

The B-17 went through several alterations in each of its design stages and variants. Of the 13 YB-17s ordered for service testing, 12 were used by the 2nd Bomb Group of Langley Field, Virginia to develop heavy bombing techniques, and the 13th was used for flight testing at the Material Division at Wright Field, Ohio.[27] Experiments on this aircraft led to the use of a turbo-supercharger, which would become standard on the B-17 line. A 14th plane, the Y1B-17A, originally destined for ground testing only, was upgraded with the turbocharger. When this aircraft had finished testing, it was re-designated the B-17A, and in April 1938 was the first aircraft to enter service under the B-17 designation.[27][29]

As the production line developed, Boeing engineers continued to improve upon the basic design. To enhance performance at slower speeds, the B-17B was altered to include larger rudder and flaps.[43] The B-17C changed from gun blisters to flush, oval-shaped windows.[73] Most significantly, with the B-17E version, the fuselage was extended by 10 ft (3.0 m), a much larger vertical fin and rudder were incorporated into the original design, a gunner's position in the tail and an improved nose were added. The engines were upgraded to more powerful versions several times, and similarly, the gun stations were altered on numerous occasions to enhance their effectiveness.[75]

By the time the definitive B-17G appeared, the number of guns had been increased from seven to 13, the designs of the gun stations were finalized, and other adjustments were complete. The B-17G was the final version of the B-17, incorporating all changes made to its predecessor, the B-17F, and in total 8,680 were built, the last one on 9 April 1945.[77] Many B-17Gs were converted for other missions such as cargo hauling, engine testing and reconnaissance.[78] Initially designated SB-17G, a number of B-17Gs were also converted for search-and-rescue duties, later to be redesignated B-17H.[79]

Two versions of the B-17 were flown under different designations. These were the XB-38 and the YB-40. The XB-38 was an engine test-bed for Allison V-1710 liquid-cooled engines, should the Wright engines normally used on the B-17 become unavailable. The YB-40 was a heavily armed modification of the standard B-17 used before the P-51 Mustang, an effective long-range fighter, became available to act as escort. Additional armament included a power turret in the radio room, a chin turret (which went on to become standard with the B-17G) and twin .50 caliber (12.7 mm) guns in the waist positions. The ammunition load was over 11,000 rounds, making the YB-40 well over 10,000 lb (4,500 kg) heavier than a fully loaded B-17F. Unfortunately, the YB-40s with their numerous heavy modifications had trouble keeping up with empty bombers, and so, together with the advent of the P-51 Mustang, the project was abandoned and finally phased out in July 1943.[80][81]

assigned to the 2nd ERS as a Search and Rescue aircraft.

Late in World War II, at least 25 B-17s were fitted with radio controls, loaded with 20,000 pounds (9,000 kg) of high-explosives, dubbed "BQ-7 Aphrodite missiles". "Attacks on the V-site bunkers were also initiated by the Americans using radio controlled bombers packed with 25,000 lb (11,000 kg). of Torpex and TNT. Called Aphrodite drones, operation 'CASTOR' was begun on June 23, 1944, using the 388th Bombardment Group at Knettishall. An airfield in a sparsely populated area of Norfolk was chosen at RAF Fersfield.[82] The drone was usually a B-17 Fortress with a B-34 Ventura being used to control the aircraft and crash it onto its target."[83] "The first four drones were sent to Mimoyecques, Siracourt, Watten and Wizernes on August 4, causing little damage. On the 6th two more B-17s were crashed on the Watten site with little success. The project came to a sudden end with the unexplained mid-air explosion over the Blyth estuary of a Liberator, part of the United States Navy's contribution as project Anvil, en route for Heligoland piloted by Lieutenant" Joseph P. Kennedy Jr., future U.S. president John F. Kennedy's elder brother. Blast damage was caused over a radius of five miles (8 km). British authorities were anxious that no similar accidents should again occur.[83] Because few (if any) BQ-7s hit their target, the Aphrodite project was scrapped in early 1945.[84][85] During and after World War II, a number of weapons were tested and used operationally on B-17s. Some of these weapons included "razons" (radio-guided) glide bombs, and Ford-Republic JB-2 Loons, also nicknamed Thunderbugs — American reverse-engineered models of the German V-1 Buzz Bomb. A much-used travelling airborne shot of a V-1/JB-2 launch in World War II documentaries was filmed from a USAF A-26 of the Air Proving Grounds, Eglin Air Force Base, launched from Santa Rosa Island, Florida. In the late 1950s, the last B-17s in United States Air Force service were QB-17 drones and DB-17P drone controllers, plus a few polished VB-17 squadron "hacks" (a 1953 request by the Wright Air Development Center to redesignate the QB-17s to Q-7 was turned down by Air Research & Development Command). The last operational mission flown by a USAF Fortress was conducted on 6 August 1959, when DB-17P 44-83684 directed QB-17G 44-83717 out of Holloman Air Force Base as a target for a Falcon air-to-air missile fired from an F-101 Voodoo fighter. A retirement ceremony was held several days later at Holloman, after which 44-83684 was retired to the Military Aircraft Storage and Disposition Center (MASDC) at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base.

Operators

The B-17 was a versatile aircraft, serving in dozens of USAAF units in theaters of combat throughout World War II, and in non-bomber roles for the RAF. Its main use was in Europe, where its shorter range and smaller bombload relative to other aircraft available did not hamper it as much as in the Pacific Theater. Peak USAAF inventory (in August 1944) was 4,574 worldwide.[36]

Argentina

Argentina Bolivia

Bolivia Brazil

Brazil Canada

Canada Colombia

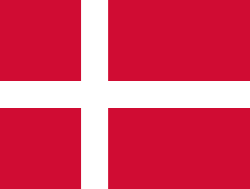

Colombia Denmark

Denmark Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic France

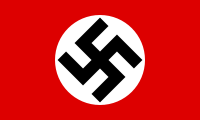

France Germany

Germany Iran

Iran Israel

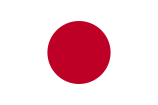

Israel Japan

Japan Mexico

Mexico Nicaragua

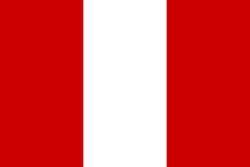

Nicaragua Peru

Peru Portugal

Portugal South Africa

South Africa Soviet Union

Soviet Union Sweden

Sweden United Kingdom

United Kingdom United States

United States

Survivors

There are some 42 surviving intact Fortresses, with about twelve operational (depending on maintenance requirements).

The Fortress as a symbol

The B-17 Flying Fortress has become, for many reasons, an icon of American power and a symbol of its Air Force. It achieved a lasting fame in the general public, which has eluded most other bomber aircraft.[8]

During the 1930s, the USAAC, as articulated by then-Major General Frank Maxwell Andrews and the Air Corps Tactical School, touted the bomber as a strategic weapon.[86] General Henry H. Arnold, Chief of the Air Corps, recommended the development of bigger aircraft with better performance and the Tactical School agreed completely.[87] The B-17 was exactly what the Air Corps was looking for; it was a high-flying, long-ranging potent bomber capable of defending itself.

When the Model 299 was rolled out on 28 July 1935, bristling with multiple machine gun installations, Richard Williams, a reporter for the Seattle Times coined the name "Flying Fortress" with his comment "Why, it's a flying fortress!".[9] Boeing was quick to see the value of the name and had it trademarked for use.

After the initial B-17s were delivered to the Air Corps 2nd Bombardment Group, they began sending them on promotional flights emphasizing its great range and navigational precision. In early 1938, Group commander Colonel Robert C. Olds flew a YB-17 from the east to west coast, setting a transcontinental record of 12 hours 50 minutes. He also broke the west-to-east coast record on the return trip, averaging 245 mph (394 km/h) in ten hours 46 minutes. Six bombers of the 2nd Bombardment group took off from Langley Field on 15 February 1938 as part of a good will flight to Buenos Aires, Argentina. Covering 12,000 miles (19,000 km) they returned on 27 February.[72] In a well publicized mission, three B-17s, "intercepted" and took photographs of the Italian ocean liner SS Rex 800 miles (1,300 km) off the Atlantic coast.[26]

8th AF 398th BG 601st BS

damaged on bombing mission over Cologne, Germany on 15 October 1944.

Pilot 1st Lt. Lawrence De Lancey brought the wounded Fortress back to Nuthampstead, UK, where photo was taken.

Notice the upwards effect of the anti-aircraft shell;

the bombardier S/Sgt. George E. Abbott was killed.

The Flying Fortress found a place in the public psyche as well. In 1943, Consolidated Aircraft commissioned a poll to see “to what degree the public is familiar with the names of the Liberator and the Flying Fortress.” Of 2,500 men in cities where Consolidated ads had been run in newspapers, only 73 percent had heard of the B-24 Liberator, while 90 percent knew of the B-17.[8]

Hollywood featured the airplane in its movies, such as Twelve O'Clock High, with Gregory Peck.[88] This film was made with the full cooperation of the United States Air Force and made use of actual combat footage. In 1964, the movie was made into a television show of the same name, and ran for three years. The B-17 also appeared in the 1938 movie Test Pilot with Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy and again with Clark Gable in Command Decision in 1948.

During the war, the largest offensive bombing force, the Eighth Air Force, was run by officers who openly preferred the B-17. Lt Gen Jimmy Doolittle wrote about his preference for equipping the Eighth with B-17s, citing the logistical advantage in keeping fielded forces down to a minimum number of aircraft types with their unique servicing and spares. For this reason, he wanted B-17 bombers and P-51 fighters for the Eighth. His views were supported by Eighth Air Force statisticians, whose studies purportedly showed that Fortresses had utility and survivability much greater than that of the B-24.[8]

Loved by its crews for bringing them home despite extensive battle damage, its durability, especially in belly-landings and ditchings, quickly took on mythical proportions.[89][90][7] Stories and photos of B-17s surviving battle damage widely circulated, boosting its iconic status.[8] Despite an inferior performance and bombload compared to the more numerous B-24 Liberator,[9] a survey of Eighth Air Force crews showed a much higher rate of satisfaction in the B-17.[10]

The most famous B-17, the Memphis Belle, toured the U.S. with its crew to reinforce national morale (and to sell War Bonds), and starred in a USAAF documentary, Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress.[91]

After the war ended, most B-17s were scrapped, but the U.S. Air Force did keep some B-17s for VIP transports and drone directors. The United States Navy and U.S. Coast Guard obtained thirty B-17s beginning in 1945 for over-water patrols as PB-1Gs, an air rescue aircraft similar to USAF B-17Hs, and PB-1Ws, a patrol aircraft with early warning radar installations aboard. The war ended before any PB-1Ws were operational and defensive armament was subsequently deleted. The Coast Guard retired the last PB-1G, BuNo 77254, in October 1959, making it the last U.S. military Flying Fortress in operation.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the surviving Fortresses had to earn their keep, as operation of a four-engine aircraft was costly, and the Warbirds preservation movement had not yet begun. The preservation of the remaining Fortresses gained steam when firebomber B-17s began to come on the market in the 1970s.

Notable B-17s

- Aluminum Overcast

- Memphis Belle

- My Gal Sal

- Nine-O-Nine

- Old 666

- Sally B

- Shoo Shoo Baby

- Texas Raiders

- The Swoose

Noted B-17 pilots and crew members

Medal of Honor awards

Many B-17 crew members received military honors and 17 received the Medal of Honor, the highest military decoration awarded by the United States:[33]

- Brig Gen Frederick Castle[92]

- 2nd Lt Robert Femoyer[93]

- 1st Lt Donald Gott[94]

- 2nd Lt David Kingsley[95]

- 1st Lt William R. Lawley, Jr.[96]

- Sgt Archibald Mathies (awarded posthumously)[97]

- 1st Lt Jack Mathis (the first airman in the European theater to be awarded the Medal of Honor)[98]

- 2nd Lt William E. Metzger, Jr.[94]

- 1st Lt Edward Michael[99]

- 1st Lt John C. Morgan[100]

- Capt Harl Pease[101]

- 2nd Lt Joseph Sarnoski (awarded posthumously)[102]

- S/Sgt Maynard H. Smith (the first enlisted airman ever to be awarded the Medal of Honor)[103]

- 1st Lt Walter E. Truemper (awarded posthumously)[97]

- S/Sgt Forrest L. Vosler[104]

- Brig Gen Kenneth Walker[105]

- Maj Jay Zeamer, Jr.[106]

Other military achievements or events

- 1st Lt Richard Bailey- Piloted "Big Red". Shot up and recovered. Awarded Distinguished Flying Cross, Purple Heart, Presidential Unit Citation, Air Medal. Retired as Major.

- Allison C. Brooks (1917–2006) — Was awarded numerous military decorations, and was ultimately promoted to the rank of Major General and served in active duty until 1971.

- Capt Werner G. Goering — American-born nephew of the Nazi Commander of the Luftwaffe in World War II, Hermann Goering.[107]

- Immanuel J. Klette (1918–1988) — Second-generation German-American whose 91 combat missions were the most flown by any Eighth Air Force pilot in World War II.[108]

- Colin Kelly (1915–1941) — Pilot of the first U.S. B-17 lost in action.[109]

- Col Frank Kurtz (1911–1996) — The USAAF's most decorated pilot of World War II; Commander of the 463rd Bombardment Group (Heavy), 15th Air Force, Celone Field, Foggia, Italy; Clark Field Philippines attack survivor; Olympic bronze medalist in diving (1932), 1944–1945; father of actress Swoosie Kurtz.

- Gen Curtis LeMay (1906–1990) — Became head of the Strategic Air Command and head of the USAF.

- Lt Col Nancy Love (1914–1976) and Betty (Huyler) Gillies (1908–1998) — The first women to be certified to fly the B-17, in 1943.[110]

- Col Robert K. Morgan (1918–2004) — Pilot of Memphis Belle.

- Lt Col Robert Rosenthal (1917–2007) - Commanded the only surviving B-17, "Rosie's Riveters", of a US 8th Air Force raid by the 100th Bomb Group on Münster in 1943, earned sixteen medals for gallantry (including one each from Britain and France), and led the raid on Berlin on February 3, 1945 that is likely to have ended the life of Roland Freisler, the Third Reich's infamous "hanging judge".

- Brig Gen Paul Tibbets (1915–2007) — Flew with the 97th Bombardment Group (Heavy) with both the 8th Air Force in England and the 12th Air Force in North Africa; later pilot of the B-29 Enola Gay dropping the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan.

- Robert Webb (1922–2002) — One of the youngest bomber pilots in the U.S. Army Air Forces.

- 1st Lt Eugene Emond (1921–1998) — Lead Pilot for Man O War II Horsepower Limited received the Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with 3 Oak Leaf Clusters, American Theater Ribbon and Victory Ribbon. Was part of D-Day and witnessed one of the first German jets when a ME-262 flew through his formation over Germany - One of the youngest bomber pilots in the U.S. Army Air Forces .

Civilian achievements or events

- Martin Caidin (1927–1997) — Author of Cyborg, the story that formed the basis of The Six Million Dollar Man and the saga of the last transatlantic formation flight of B-17s ever made, Everything But the Flak.

- Clark Gable (1901–1960) — Academy Award-winning film actor, five missions as waist gunner with several groups from May to September 1943, including the B-17 Eight Ball of the 359th Bomb Squadron (351st Bomb Group).

- Tom Landry (1924–2000) — American football player and coach, flew 30 missions over Europe in 1944–45 as a B-17 pilot with the 493rd Bomb Group, surviving a crash landing in Czechoslovakia. (His older brother Robert died in a B-17 crash)[111]

- Norman Lear — Radio operator, with the 463rd Bombardment Group (Heavy), 15th Air Force, Celone Field, Foggia, Italy; television producer of American sitcoms Sanford and Son, Maude and All in the Family, among others.

- Gene Roddenberry (1921–1991) — Creator of Star Trek; flew B-17s for the 394th Bomb Squadron, 5th Bomb Group (H), in the Pacific theater.[112]

- Robert Rosenthal (1917–2007) — Assistant to the U.S. prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials, where he interrogated Hermann Goering, pilot with the 100th Bomb Group.

- Brigadier General Robert Lee Scott, Jr. (1908–2006) — Best known for his autobiography God is My Co-Pilot, about his exploits in World War II with the Flying Tigers and the United States Army Air Forces in China and Burma.

- James Stewart (1908–1997) — Academy Award-winning film actor, instructed in B-17s before flying 20 combat missions in B-24s with the 8th Air Force, England; retired from Air Force Reserve as a Brigadier General.[113]

- Bert Stiles (1920–1944) — 91st Bomb Group co-pilot from March to October 1944, short-story author, killed in action flying a P-51 on a second tour.

- Smokey Yunick (1923–2001) — Award-winning motorsports car designer and premier NASCAR crew chief flew 50 missions as a B-17 pilot with the 97th Bombardment Group (Heavy) of the 15th Air Force, out of Amendola Airfield, Foggia, Italy.[114]

Specifications (B-17G)

Data from The Encyclopedia of World Aircraft[28]

General characteristics

- Crew: 10: Pilot, co-pilot, navigator, bombardier/nose gunner, flight engineer-top turret gunner, radio operator, waist gunners (2), ball turret gunner, tail gunner[115]

- Length: 74 ft 4 in (22.66 m)

- Wingspan: 103 ft 9 in (31.62 m)

- Height: 19 ft 1 in (5.82 m)

- Wing area: 1,420 ft² (131.92 m²)

- Airfoil: NACA 0018 / NACA 0010

- Empty weight: 36,135 lb (16,391 kg)

- Loaded weight: 54,000 lb (24,495 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 65,500 lb (29710 kg)

- Powerplant: 4× Wright R-1820-97 "Cyclone" turbosupercharged radial engines, 1,200 hp (895 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 287 mph (249 knots, 462 km/h)

- Cruise speed: 182 mph (158 knots, 293 km/h)

- Range: 1,738 nmi (2,000 mi, 3,219 km) with 2,722 kg (6,000 lb) bombload

- Service ceiling 35,600 ft (10,850 m)

- Rate of climb: 900 ft/min (4.6 m/s)

- Wing loading: 38.0 lb/ft² (185.7 kg/m²)

- Power/mass: 0.089 hp/lb (150 W/kg)

Armament

- Guns: 13× M2 Browning .50 caliber (12.7 mm) machine guns in twin turrets, plus single dorsal, fore and aft beam positions (with optional extra nose armament fitted in glazed nose).

- Bombs: **Short range missions (<400 mi): 8,000 lb (3,600 kg)

- Long range missions (≈800 mi): 4,500 lb (2,000 kg)

See also

- B-17 Flying Fortress variants

Related development

- Boeing XB-15

- XB-38 Flying Fortress

- YB-40 Flying Fortress

- C-108 Flying Fortress

Comparable aircraft

- Avro Lancaster

- B-24 Liberator

- Focke-Wulf Fw 200

- Handley Page Halifax

- Heinkel He 177

- Junkers Ju 290

- Petlyakov Pe-8

- Piaggio P.108B

- Short Stirling

Related lists

- List of B-17 Flying Fortress serial numbers

- List of bomber aircraft

- List of military aircraft of the United States

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "The Boeing Logbook: 1933–1938". Boeing.com. Retrieved on 18 December 2006.

- ↑ Yenne 2006, p. 8.

- ↑ Bowers, Peter M. Fortress in the Sky. Granada Hills, California: Sentry Books Inc., 1976 ISBN 0-913194-04-2.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Carey 1998, p. 4.

- ↑ "The Story of the B-17". B-17 Pilot Training Manual. Headquarters, AAF, Office of Flying Safety. http://www.stelzriede.com/ms/html/mshwpmn1.htm#sty. Retrieved on 16 January. "The B-17's incredible capacity to take it — to come flying home on three, two, even one engine, sieve-like with flak and bullet holes, with large sections of wing or tail surfaces shot away — has been so widely publicized that U. S. fighting men could afford to joke about it" and "one important fact stands clear-cut now. The Flying Fortress is a rugged airplane".

- ↑ Browne, Robert W. (Winter 2001). "The Rugged Fortress: Life-Saving B-17 Remembered" (– Scholar search). Flight Journal: WW II Bombers (Winter 2001). http://www.rccaraction.com/fj/articles/b-17/fortress_1.asp.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "B-17 Flying Fortress". www.b17fortress.de (2006). Retrieved on 17 January 2007. "General Ira C. Eaker, commander of the Eighth Air Force during World War II described the aircraft as "the best bomber which was ever built. She could handle extensive damage and still stay in the air.""

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Johnsen, Frederick A. (2006). "The Making of an Iconic Bomber". Air Force Magazine 89 (10). http://www.afa.org/magazine/Oct2006/1006bomber.asp.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Baugher, Joe. "Boeing Model 299". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Retrieved on 12 January 2007.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "B-17:Best Airplane". B-17 Flying Fortress:Queen of the Skies. Retrieved on 9 January 2007.

- ↑ Yenne, Bill (2005). The story of the Boeing Company. St. Paul, Minn.: Zenith. pp. 46. ISBN 0-7603-2333-X.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 "Aviation Photography:B-17 Flying Fortress". Northstar Gallery. Retrieved on 16 January 2007.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Goebel, Greg (2005). "Fortress In Development: Model 299". The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. Retrieved on 9 January 2007.

- ↑ Tate 1998, p. 164.

- ↑ Salecker 2001, p. 46.

- ↑ Yenne 2006, p. 12.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Tate 1998, p. 165.

- ↑ "Model 299 Crash, 15 November 1935". National Museum of the USAF. Retrieved on 16 January 2007.

- ↑ Schamel, John. "How the Pilot's Checklist Came About". FAA Flight Service Training. Retrieved on 12 January 2007. "On board the plane were pilots Major Ployer P. Hill (his first time flying the 299) and Lieutenant Donald Putt (the primary Army pilot for the previous evaluation flights), Leslie Tower, Boeing mechanic C.W. Benton, and Pratt and Whitney representative Henry Igo. Putt, Benton and Igo escaped with burns, and Hill and Tower were pulled from the wreckage alive, but later died from their wounds."

- ↑ Salecker 2001, p. 48.

- ↑ Goebel, Greg (2005). "Model 299 Flying Fortress". The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. Retrieved on 9 January 2007. "The Model 299 cost almost $200,000, more than twice as much as either of its two competitors."

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Bowers 1976, p. 37.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Meilinger, Phillip S. (October 2004). "When the Fortress Went Down". Air Force Magazine (Air Force Association) 87 (9). http://www.afa.org/magazine/Oct2004/1004fort.asp.

- ↑ Schamel, John. "How the Pilot's Checklist Came About". FAA Flight Service Training. Retrieved on 12 January 2007. "The idea of a pilot's checklist spread to other crew members, other Air Corps aircraft types, and eventually throughout the aviation world."

- ↑ Maurer Maurer, "Aviation in the U.S. Army, 1919–1939", United States Air Force Historical Research Center, Office of Air Force History, Washington, D.C., 1987, ISBN 0-912799-38-2, pages 406-408.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Intercepting The “Rex”". National Museum of the USAF. Retrieved on 9 January 2007.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 "BOEING Y1B-17". National Museum of the USAF. Retrieved on 9 January 2007.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Donald 1997, p. 155.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Goebel, Greg (2005). "Y1B-17/Y1B-17A". The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. Retrieved on 9 January 2007.

- ↑ Baugher, Joe. "Boeing Y1B-17A/B-17A". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Retrieved on 15 January 2007.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Goebel, Greg (2005). "B-17B/B-17C/B-17D". The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. Retrieved on 9 January 2007.

- ↑ "Boeing B-17B". National Museum of the USAF. Retrieved on 9 January 2007.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Eylanbekov, Zaur (2006). "Airpower Classics:B-17 Flying Fortress" (PDF). Air Force Magazine. Retrieved on 8 January 2007.

- ↑ Serling 1992, p. 55. Quote: "At the peak of production, Boeing was rolling out as many as 363 B-17s a month — averaging between 14 and 16 Forts a day, the most incredible production rate for large aircraft in aviation history… Prior to the B-17, the Boeing Y1B-9 (first flight: 1931) had only seven production aircraft, the Martin B-10 (first flight: 1932) had total production of 213, the Farman F.222 (first flight: 1932) had only 24 constructed and the Handley Page Heyford (first flight: 1933) had a total of 125 built. The B-17 easily eclipsed these numbers."

- ↑ Yenne 2006, p. 6.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Baugher, Joe. "B-17 Squadron Assignments". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Retrieved on 15 January 2007.

- ↑ Yenne 2006, p. 23.

- ↑ Chant, Christopher (1996). Warplanes of the 20th Century. London: Tiger Books International. pp. 61–62. ISBN 1-85501-807-1.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Goebel, Greg (2005). "RAF Fortress I In Combat". The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. Retrieved on 9 January 2007.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Baugher, Joe. "Fortress I for RAF". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Retrieved on 15 January 2007.

- ↑ Gustin, Emmanuel. "Boeing B-17". uboat.net. Retrieved on 2 April 2007.

- ↑ "U-627". Uboat.net. Retrieved on 2 April 2007.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Baugher, Joe. "Boeing B-17B Fortress". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Retrieved on 15 January 2007.

- ↑ "Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress – USA". The Aviation History Online Museum. Retrieved on 16 January 2007.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Goebel, Greg (2005). "Fortress Over Europe". The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. Retrieved on 9 January 2007.

- ↑ Walden, Geoff (January 2007). "Third Reich in Ruins:Schweinfurt". www.thirdreichruins.com. Retrieved on 16 January 2007.

- ↑ Hess 1994, p. 67.

- ↑ Hess 1994, pp.69–71.

- ↑ Caldwell and Muller 2007, pp. 151–152.

- ↑ McKillop, Jack. "Combat Chronology of the U.S. Army Air Forces: February 1944". www.usaaf.net. Retrieved on 17 January 2007.

- ↑ Caldwell and Muller 2007, p. 162.

- ↑ McKillop, Jack. "Combat Chronology of the U.S. Army Air Forces: April 1945". www.usaaf.net. Retrieved on 17 January 2007.

- ↑ Arakaki and Kuborn 1991, pp. 73–75, 158–159.

- ↑ Arakaki and Kuborn 1991, pp. 73, 158-159.

- ↑ Salecker 2001, pp. 64–71.

- ↑ Sakai, Saburo, with Martin Caiden and Fred Saito. Samurai!. Naval Institute Press. pp. 68–72.

- ↑ Anniversary talks — Battle of the Bismarck Sea, 2–4 March 1943 [Australian War Memorial]

- ↑ Frisbee 1990

- ↑ "History:B-17 Flying Fortress". Boeing.com. Retrieved on 16 January 2007.

- ↑ "Formation". www.b17flyingfortress.de. Retrieved on 9 January 2007.

- ↑ "Formation". B-17 Pilot Training Manual. Headquarters, AAF, Office of Flying Safety. http://www.stelzriede.com/ms/html/mshwpmn2.htm#form. Retrieved on 16 January.

- ↑ Caidin, Martin (1960). Black Thursday. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co. Inc.. ISBN 0-553-26729-9.

- ↑ Hoffman, Wally (2006). "We Get Our Feet Wet". Magweb.com. Retrieved on 18 July 2006.

- ↑ Caidin 1960, p. 86.

- ↑ "Battle-damaged B-17s". www.daveswarbirds.com. Retrieved on 16 January 2007.

- ↑ Price, Alfred (September 1993). "Against Regensburg and Schweinfurt". Air Force Magazine 76 (9). http://www.afa.org/magazine/1993/0993against.asp.

- ↑ Schollars, Todd J. (Fall 2003). "German wonder weapons: degraded production and effectiveness". Air Force Journal of Logistics. Retrieved on 16 January 2007.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Law, Ricky (1997). "Dornier Do 200". Arsenal of Dictatorship. Retrieved on 16 January 2007.

- ↑ Goebel, Greg (2005). "Fortress Oddballs". The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. Retrieved on 9 January 2007.

- ↑ http://home.att.net/~jbaugher2/b17_19.html

- ↑ Baugher, Joe. "B-17 Commercial Transports". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Retrieved on 15 January 2007.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Baugher, Joe. "Boeing Y1B-17". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Retrieved on 15 January 2007.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Baugher, Joe. "Boeing B-17C Fortress". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Retrieved on 15 January 2007.

- ↑ Baugher, Joe. "Boeing B-17D Fortress". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Retrieved on 15 January 2007.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Baugher, Joe. "Boeing B-17E Fortress". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Retrieved on 15 January 2007.

- ↑ Baugher, Joe. "Boeing B-17F Fortress". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Retrieved on 15 January 2007.

- ↑ "Chronicle". www.b17flyingfortress.de. Retrieved on 16 January 2007.

- ↑ Goebel, Greg (2005). "B-17G/Fortress Triumphant". The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. Retrieved on 9 January 2007.

- ↑ Baugher, Joe. "Boeing B-17H". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Retrieved on 15 January 2007.

- ↑ Baugher, Joe. "Vega XB-38". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Retrieved on 15 January 2007.

- ↑ Baugher, Joe. "Boeing YB-40". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Retrieved on 15 January 2007.

- ↑ near Winfarthing

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Ramsey, Winston G. The V-Weapons. London, United Kingdom: After The Battle, Number 6, 1974, page 20.

- ↑ Baugher, Joe. "History of the BQ-7". Encyclopedia of American Aircraft. Retrieved on 15 January 2007.

- ↑ Parsch, Andreas (March 2003). "Boeing BQ-7 Aphrodite". Directory of U.S. Military Rockets and Missiles. Retrieved on 16 January 2007.

- ↑ Tate 1998, pp. 149–150. Quote: "The Howell Commission's report…stated "…an adequate striking force for use against objectives both near and remote is a necessity for a modern army…"

- ↑ Tate 1998, p. 161. Quote: "To them it seemed that the bomber was well-nigh invincible. They argued that pursuit was obsolete and attack an expensive luxury, since aviation was more effective when used for interdiction behind enemy lines and strategic bombardment to destroy the enemy's means and will to fight."

- ↑ "Twelve O'Clock High (1949)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved on 16 January 2007.

- ↑ "The Story of the B-17". B-17 Pilot Training Manual. Headquarters, AAF, Office of Flying Safety. http://www.stelzriede.com/ms/html/mshwpmn1.htm#sty. "The B-17's incredible capacity to take it — to come flying home on three, two, even one engine, sieve-like with flak and bullet holes, with large sections of wing or tail surfaces shot away — has been so widely publicized that U.S. fighting men could afford to joke about it" and "one important fact stands clear-cut now. The Flying Fortress is a rugged airplane".

- ↑ Browne, Robert W. (Winter 2001). "The Rugged Fortress: Life-Saving B-17 Remembered" (– Scholar search). Flight Journal: WW II Bombers (Winter 2001). http://www.rccaraction.com/fj/articles/b-17/fortress_1.asp.

- ↑ "The Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress (1944)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved on 16 January 2007.

- ↑ Frisbee, John L. "Valor: The Quiet Hero." Air Force Magazine Volume 71, Issue 3, March 1998.}}

- ↑ Frisbee, John L. "Valor:'I Am the Captain of My Soul'". Air Force Magazine Volume 68, Issue 5, May 1985.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Frisbee, John L. "Valor: 'Valor at its Highest'". Air Force Magazine Volume 72, Issue 6, June 1989.

- ↑ Frisbee, John L. "Valor: A Rather Special Award." Air Force Magazine Volume 73, Issue 8, August 1990.

- ↑ Frisbee, John L. "Valor: One Turning and One Burning." Air Force Magazine Volume 82, Issue 6, June 1999.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Frisbee, John L. "Valor: A Point of Honor." Air Force Magazine Volume 68, Issue 8, August 1985.

- ↑ Frisbee, John L. "Valor: A Tale of Two Texans." Air Force Magazine Volume 69, Issue 3, March 1986.

- ↑ Frisbee, John L. "Valor: Gauntlet of Fire." Air Force Magazine Volume 68, Issue 8, August 1985.

- ↑ Frisbee, John L. "Valor: Crisis in the Cockpit." Air Force Magazine Volume 67, Issue 1, January 1984.

- ↑ Frisbee, John L. "Valor: Rabaul on a Wing and a Prayer." Air Force Magazine Volume 73, Issue 7, July 1990.

- ↑ "MOH citation of SARNOSKI, JOSEPH R.". Retrieved on 12 January 2007.

- ↑ Frisbee, John L. "Valor: First of the Few." Air Force Magazine Volume 67, Issue 4, April 1984.

- ↑ Frisbee, John L. "Valor: The Right Touch." Air Force Magazine Volume 81, Issue 9, September 1998.

- ↑ Frisbee, John L. "Valor: Courage and Conviction." Air Force Magazine Volume 73, Issue 10, October 1990.

- ↑ Frisbee, John L. "Valor: Battle Over Bougainville." Air Force Magazine Volume 68, Issue 12, December 1985.

- ↑ Gobrecht, Harry D. (2006). "Werner G. Goering Crew – 358th BS". Hell's Angels: Home of the 303rd Bomb Group (H) Association. Retrieved on 20 December 2006.

- ↑ Freeman 1993, pp. 497–500.

- ↑ Frisbee, John L. "Valor: Colin Kelly (He was a Hero in Legend and in Fact)." Air Force Magazine Volume 77, Issue 6, June 1994.

- ↑ "National Museum of the USAF, Biography of Nancy Harkness Love".

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Alexander, David (1994). Star Trek Creator. New York, New York: ROC. pp. 57–78. ISBN 0451545189.

- ↑ Smith, Starr (2005). Jimmy Stewart: Bomber Pilot. St. Paul, Minnesota: Zenith Press. ISBN 0-76032-199-X.

- ↑ Yunick, Henry (2003). Best Damn Garage in Town: My Life & Adventures. Carbon Press. pp. 650.

- ↑ "B-17 Flying Fortress Crew Positions". Arizona Wing CAF Museum. Retrieved on 16 January 2007. "describes in detail the various positions and their related duties. The Boeing Pilot Manual also describes duties."

Bibliography

- Arakaki, Leatrice R. and John R. Kuborn. 7 December 1941: The Air Force Story. Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii: Pacific Air Forces, Office of History, 1991. ISBN 0-912799-73-0.

- Birdsall, Steve. The B-17 Flying Fortress. Dallas, Texas: Morgan Aviation Books, 1965.

- Bowers, Peter M. Boeing Aircraft Since 1916. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1989. ISBN 0-37000-016-1.

- Bowers, Peter M. Fortress In The Sky, Granada Hills, California: Sentry Books, 1976. ISBN 0-913194-04-2.

- Bowman, Martin W. Castles in the Air: The Story of the B-17 Flying Fortress Crews of the U.S. 8th Air Force. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books, 2000, p. 216. ISBN 1-57488-320-8.

- Caidin, Martin. Black Thursday. New York: E.P. Dutton & Company, 1960. ISBN 0-553-26729-9.

- Caldwell, Donald and Richard Muller. The Luftwaffe over Germany: Defense of the Reich. London: Greenhill Books Publications, 2007. ISBN 978-1-85367-712-0.

- Carey, Brian Todd. "Operation Pointblank: Evolution of Allied Air Doctrine During World War II." World War II, November 1998. Retrieved: 15 January 2007.

- David, Donald. "Boeing Model 299 (B-17 Flying Fortress)." The Encyclopedia of World Aircraft. Etobicoke, Ontario, Canada: Prospero Books, 1997. ISBN 1-85605-375-X.

- Davis, Larry. B-17 in Action. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1984. ISBN 0-89747-152-0.

- Freeman, Roger A. B-17 Fortress at War. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1977. ISBN 0-684-14872-2.

- Frisbee, John L. "Valor: Courage and Conviction." Air Force Magazine Volume 73, Issue 10, October 1990.

- Hess, William N. B-17 Flying Fortress: Combat and Development History of the Flying Fortress. St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbook International, 1994. ISBN 0-87938-881-1.

- Hess, William N. B-17 Flying Fortress Units of the MTO. Botley, Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing Limited, 2003. ISBN 1-84176-580-5.

- Hess, William N. Big Bombers of WWII. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Lowe & B. Hould, 1998. ISBN 0-681-07570-8.

- Hoffman, Wally and Rouyer, Philipppe. "La guerre à 30 000 pieds" . Louviers : Ysec Editions, 2008. ISBN 9782846731096. [Available only in French]

- Jablonski, Edward. Flying Fortress. New York: Doubleday, 1965. ISBN 0-385-03855-0.

- Johnsen, Frederick A. Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. Stillwater, Minnesota: Voyageur Press, 2001. ISBN 1-58007-052-3.

- Johnsen, Frederick A. "The Making of an Iconic Bomber." Air Force Magazine, Volume 89, Issue 10, 2006. Retrieved: 15 January 2007.

- Lloyd, Alwyn T. B-17 Flying Fortress in Detail and Scale. Fallbrook, California: Aero Publishers, 1986. ISBN 0-8168-5029-1.

- O'Leary, Michael. Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress (Osprey Production Line to Frontline 2). Botley, Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 1999. ISBN 1-85532-814-3.

- Salecker, Gene Eric. Fortress Against The Sun – The B-17 Flying Fortress in the Pacific. Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: Combined Publishing, 2001 ISBN 1-58097-049-4.

- Serling, Robert J. Legend & Legacy: The Story of Boeing and its People. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992. ISBN 0-312-05890-X.

- Tate, Dr. James P. "The Army and Its Air Corps: Army Policy toward Aviation 1919–1941." Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air University Press, 1998. ISBN 1-42891-257-6. Retrieved: 1 August 2008.

- Thompson, Scott A. Final Cut: The Post War B-17 Flying Fortress, The Survivors: Revised and Updated Edition. Highland County, Ohio: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 2000. ISBN 1-57510-077-0.

- Trescott, Jacqueline. "Smithsonian Panel Backs Transfer of Famed B-17 Bomber." Washington Post Volume 130, Issue 333, 3 November 2007.

- Willmott, H.P. B-17 Flying Fortress. London: Bison Books, 1980. ISBN 0-85368-444-8.

- Yenne, Bill. B-17 at War. St Paul, Minnesota: Zenith Imprint, 2006. ISBN 0-7603-2522-7.

External links

- Big Yank History

- ~ NEW ~ American Combat Planes of the 20th Century by Ray Wagner

- Bail Out Over the Balkans - True Story by B17 Pilot Richard Munsen after being shot down over Yugoslavia

- Commemorative Air Force Gulf Coast Wing - Home of B-17G "Texas Raiders"

- Official site of the 303rd "Hell's Angels" Bomb Group

- Official site of the 398th "Hell From Heaven" Bomb Group

- Official site of the 463rd "The Swoose" Bomb Group

- Information on Sally B

- World War II 8th Air Force website

- Warbird Alley: B-17 page — Information about B-17s still flying today.

- Sam Hewitt: 15th Air Force WWII POW

- Lacey Lady — TheBomber.com

- The Most Unbelieveable Landing of a B-17

- The Air War in Retrospect — First-hand accounts of WWII Veterans.

- Lt. Bob Swan's Photos of Life as a B-17 Flying Fortress Navigator in England during WWII

- Second-Lieutenant David Kingsley, the Ultimate Sacrifice

- Arizona Wing of the Commemorative Air Force & Their Touring B-17 — Sentimental Journey

- The EAA's Touring B-17 — Aluminum Overcast

- Fantasy of Flight's B17 — B-17 Flying Fortress on display at Fantasy of Flight.

- Battle-Damaged B-17s — Photographic chronicle of the damage that the "Queen of the Skies" could sustain and still bring her crews home.

- Warbirdregistry.org

- Photograph of USAF B-17 and crew that crash landed in neutral Ireland in WWII

- List Of Surviving B-17s

- List Of B-17s and B-24s downed in France between 1942 and 1945 - 778 aircraft and more than 6500 crew members

- Crew 21 - 96BG 337BS 1943 East Anglia, UK.

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||