Azerbaijani language

| Azerbaijani آذربایجان دیلی (Perso-Arabic script) Азәрбајҹан дили (Cyrillic script) Azərbaycan dili (Latin script) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation: | /azærbajʤan dili/ | |

| Spoken in: | also in parts of neighboring countries such as: |

|

| Total speakers: | 31 million [2] | |

| Ranking: | 34th (native speakers) | |

| Language family: | Altaic[3] (controversial) Turkic Oghuz Azerbaijani |

|

| Writing system: | Latin alphabet for North Azeri in Azerbaijan, Perso-Arabic script for South Azeri in Iran, and, formerly, Cyrillic alphabet for North Azeri (Azerbaijani variants) | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language in: | ||

| Regulated by: | No official regulation | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1: | az | |

| ISO 639-2: | aze | |

| ISO 639-3: | variously: aze – Azerbaijani (generic) azj – North Azerbaijani azb – South Azerbaijani |

|

|

||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Part of a series on |

|

|---|---|

| Culture | |

|

Architecture · Art · Cinema · Cuisine |

|

| By country or region | |

|

Iran · Georgia · Russia |

|

| Religion | |

|

Islam · Christianity · Judaism |

|

| Language | |

| Azerbaijan Portal |

|

The Azerbaijani language, also called Azeri, Azari, Azeri Turkic, or Azerbaijani Turkic, is a Turkic language spoken in Azerbaijan and northwestern Iran. North Azeri is the official language of the Republic of Azerbaijan. North Azerbaijani is the name applied to this variety of Azeri in ISO 639-3 (azj) and in Ethnologue, which is called Azərbaycan dili in Azerbaijan. This variety is also spoken in Russia's Republic of Dagestan, south-eastern and southern Georgia. South Azeri is the variety of Azeri spoken in northwestern Iran. Iranian Azeris often call it Türki , Türki Azari or Azari. This variety is mainly spoken in the northwest provinces as the dominant language of East Azarbaijan, West Azarbaijan, Ardabil, Zanjan, and in some regions of Kordestan, Qazvin, Hamadan, Gilan, Kermanshah, Qom and Markazi. Many Azeris also live in Tehran, Karaj and other regions.[4] Generally, Azeris in Iran were regarded as "a well integrated linguistic minority" by academics prior to Iran's Islamic Revolution.[5][6] South Azerbaijani is the name applied to this variety of Azeri in ISO 639-3 (azb) and in Ethnologue.

Azeri is a Turkic language of the Oghuz branch, closely related to Turkish. Azeri is mutually intelligible with other Oghuz languages, which include Turkish and Turkmen.

Contents |

History and evolution

- For the languages spoken in Azerbaijan before the Turks' arrival, see:

- Languages of Azerbaijan

- Old Azari language

The Azeri language of today is based on the Oghuz language, spread to Southwestern Asia in the course of the medieval Turkic migration, heavily influenced by Persian and Arabic.

It gradually supplanted the previous Iranian languages—Tat, Azari, and Middle Persian in northern Iran, and a variety of Caucasian languages in the Caucasus, particularly Udi, and had become the dominant language before the time of the Safavid dynasty; however, minorities in both the Republic of Azerbaijan and Iran continue to speak the earlier Iranian languages to this day, and Middle- and New Persian loanwords are numerous in Azeri.

The historical development of Azeri can be divided into two major periods: early (ca. 16th to 18th century) and modern (18th century to present). Old Azeri differs from its descendant in that it contained a much greater amount of Persian, and Arabic loanwords, phrases and syntactic elements. Early writings in Azeri also demonstrate lingustic interchangeability between Oghuz and Kypchak elements in many aspects (such as pronouns, case endings, participles, etc...). As Azeri gradually moved from being merely a language of epic and lyric poetry to being also a language of journalism and scientific research, its literary version has become more or less unified and simplified with the loss of many archaic Turkic elements, bulky Iranisms and Ottomanisms, and other words, expressions, and rules that failed to gain popularity among Azeri-speaking masses.

Between ca. 1900 and 1930, there were several competing approaches to the unification of the national language in Azerbaijan popularized by the literati. Despite major differences, they all aimed primarily at making it easy for semiliterate masses to read and understand literature. They all criticized the overuse of Persian, Arabic, Ottoman Turkish, and European (mainly Russian) elements in both colloquial and literary language and called for a more simple and popular style.

The Russian conquest of the South Caucasus in the 19th century split the speech community across two states; the Soviet Union promoted development of the language, but set it back considerably with two successive script changes - from Perso-Arabic script to Latin and then to Cyrillic - while Iranian Azeris continued to use the Perso-Arabic script as they always had. Despite the wide use of Azeri during the Soviet era, it became the official language of Azerbaijan only in 1978 (along with Georgian in Georgia and Armenian in Armenia). After independence, the Republic of Azerbaijan decided to switch again to the Latin script, following the Turkish model.

Literature

Classical literature in Azeri was formed in 14th century based on the Tabrizi and Shirvani dialects (these dialects were used by classical Azeri writers Nasimi, Fuzuli, and Khatai). Modern literature in the Republic of Azerbaijan is based on the Shirvani dialect only, while in Iran it is based on the Tabrizi one. The first newspaper in Azeri, Əkinçi was published in 1875.

In mid-19th century it was taught in the schools of Baku, Ganja, Shaki, Tbilisi, and Yerevan. Since 1845, it has also been taught in the University of St. Petersburg in Russia.

Famous literary works in Azeri are the Book of Dada Gorgud, the Epic of Köroğlu, translation of Layla and Majnun (Dâstân-ı Leylî vü Mecnûn), and Heydar Babaya Salam. Important poets and writers of the Azeri language include Imadeddin Nasimi, Muhammed Fuzuli, Hasanoglu Izeddin, Shah Ismail I, Khurshidbanu Natavan, Mirza Fatali Akhundov, Mirza Alakbar Sabir, Bakhtiyar Vahabzade, and Mohammad Hossein Shahriar.

Distribution of speakers

Most of the sources have reported the percentage of Azerbaijani-Turkic-speakers around 16-24 percent of the Iranian population.[7]

Regions where Azeri is spoken by significant group of people

- North Azeri variety 1

Azerbaijan, and southern Dagestan, along the Caspian coast in the southern Caucasus Mountains. Also spoken in Armenia, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia (Asia), Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan.

- South Azeri variety 2

East Azerbaijan and West Azerbaijan, Ardabil, Zanjan,and part of Kordestan, Hamedan, Qazvin, Markazi and Gilan provinces. Many in districts of Tehran. Some Azeri-speaking groups are in Fars Province and other parts of Iran. Also spoken in Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Iraq, Syria, Turkey (Asia)

Azeri as a lingua franca

Azeri served as a lingua franca in Daghestan, especially Southern Daghestan in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[8][9][10]

Dialects

Despite their relatively large number, dialects of Azeri do not differ substantially. Speakers of various dialects normally do not have problems understanding each other. However minor problems may occur between Azeri-speakers from the Caucasus and Iran, as some of the words used by the latter that are of Persian or Arabic origin may be unknown to the former. For example, the word firqə ("political party") used by Iranian Azeris may not be understood in Azerbaijan, where the word partiya is used to describe the same object. Such phenomenon is explained by the fact that both words have been in wide use since after the split of the two speech communities in 1828.

The following list reflects only one of several perspectives on the dialectology of Azeri. Some dialects may be varieties of others.

- Ardabil dialect (Ardabil and western Gilan, Iran)

- Ayrum dialect (northwestern Azerbaijan; northeastern Armenia1)

- Baku dialect (eastern Azerbaijan)

- Borchali dialect (southern Georgia; northern Armenia1)

- Derbent dialect (southern Russia)

- Gabala (Gutgashen) dialect (northern Azerbaijan)

- Ganja dialect (western Azerbaijan)

- Gazakh dialect (northwestern Azerbaijan)

- Guba dialect (northeastern Azerbaijan)

- Hamadan dialect (Hamadan, Iran)

- Karabakh dialect (central Azerbaijan)

- Karadagh dialect (East Azerbaijan and West Azerbaijan, Iran)

- Kars dialect (eastern Turkey and northwestern Armenia1)

- Lankaran dialect (southeast Azerbaijan)

- Maragheh dialect (East Azerbaijan, Iran)

- Mughan (Salyan) dialect (central Azerbaijan)

- Nakhichevan dialect (southwestern Azerbaijan)

- Ordubad dialect (southwestern Azerbaijan; southern Armenia1)

- Shaki (Nukha) dialect (northern Azerbaijan)

- Shirvan (Shamakhy) dialect (eastern Azerbaijan)

- Tabriz dialect (East Azerbaijan, Iran)

- Yerevan dialect (central Armenia1)

- Zagatala-Gakh dialect (northern Azerbaijan)

- Zanjan dialect (Zanjan, Iran)

Phonology

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives and affricates |

p | b | t | d | ʧ | ʤ | c | ɟ | k | ɡ | ||||||

| Nasals | m | n | ||||||||||||||

| Fricatives | f | v | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | x | ɣ | h | |||||||

| Approximants | l | j | ||||||||||||||

| Taps | ɾ | |||||||||||||||

- /ʧ/ and /ʤ/ are realised as [ʦ] and [ʣ] respectively in the areas around Tabriz and to the west, south and southwest of Tabriz (including Kirkuk in Iraq); in the Nakhchivan and Ayrum dialects, in Jabrayil and some Caspian coastal dialects;[11]

- In many dialects of Azeri, /c/ is realized as [ç] when it is found in the coda position or is preceded by a voiceless consonant (as in çörək [ʧœˈɾæç] - "bread"; səksən [sæçˈsæn] - "eighty").

- /k/ appears only in words borrowed from Russian or French (spelled, as with /c/, with a k).

- /w/ exists in the Kirkuk dialect as an allophone of /v/ in Arabic loanwords.

- In the Baku dialect, /ov/ may be realised as [oʷ], and /ev/ and /œv/ as [œʷ], e.g. /ɡovurˈma/ → [ɡoʷurˈma], /sevˈda/ → [sœʷˈda], /dœvˈran/ → [dœʷˈran]

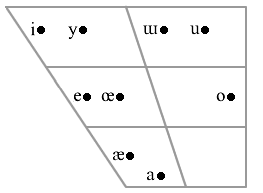

Vowels

Vowel phonemes of Standard Azeri

Alphabets

In the Republic of Azerbaijan, North Azeri now officially uses the Latin alphabet, but the Cyrillic alphabet is also in wide use, while in Iran, South Azeri uses the Perso-Arabic script. There is a one-to-one correspondence between the Latin and Cyrillic alphabets for North Azeri (although the Cyrillic alphabet has a different order):

|

|

|

|

Before 1929, Azeri was only written in the Perso-Arabic script. In 1929–1938 a Latin alphabet was in use for North Azeri (although it was different from the one used now), from 1938 to 1991 the Cyrillic alphabet was used, and in 1991 the current Latin alphabet was introduced, although the transition to it has been rather slow. If written in the Latin alphabet, all foreign words are transliterated, for example, "Bush" becomes "Buş", and "Schröder" becomes "Şröder".

South Azeri speakers in Iran have always continued to use the Perso-Arabic script, although the spelling and orthography is not yet standardized.

Nomenclature

In 1992–1993, when Azerbaijan Popular Front Party was in power in Azerbaijan, the official language of Azerbaijan was renamed by the parliament to Türk dili ("Turkic"). However, since 1994 the Soviet era name of the language, Azərbaycan dili ("Azerbaijani"), has been re-established and reflected in the Constitution. Varlıq, the most important literary Azeri magazine published in Iran, uses the term Türki ("Turkish" in English or "Torki" in Persian) to refer to the Azeri language. South Azeri speakers in Iran often refer to the language as Türki, distinguishing it from İstambuli Türki ("Anatolian Turkish"), the official language of Turkey. Some people also consider Azeri to be a dialect of a greater Turkish language and call it Azərbaycan Türkcəsi ("Azerbaijani Turkish"), and scholars such as Vladimir Minorsky used this definition in their works. ISO and the Unicode Consortium, call the macrolanguage "Azeri" and its two varieties "North Azeri" and "South Azeri". According to the Linguasphere Observatory, all Oghuz languages form part of a single 'outer language' of which "Azeri-N." and "Azeri-S." are 'inner languages'.

See also

- Azeri people

- Historical linguistics

- Language families and languages

- Old Azari language

References

- ↑ Ethnologue

- ↑ Ethnologue total for South Azerbaijani plus Ethnologue total for North Azerbaijani

- ↑ "[1] Ethnologue"

- ↑ Azarbaijanis

- ↑ Higgins, Patricia J. (1984) "Minority-State Relations in Contemporary Iran" Iranian Studies 17(1): pp. 37-71, p. 59

- ↑ Binder, Leonard (1962) Iran: Political Development in a Changing Society University of California Press, Berkeley, Calif., pp. 160-161, OCLC 408909

- ↑ N. Ghanea-Hercock, Ethnic and religious groups in the Islamic Republic of Iran. London: University of London, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, 2003, p. 6

- ↑ Pieter Muysken, "Introduction: Conceptual and methodological issues in areal linguistics", in Pieter Muysken, From Linguistic Areas to Areal Linguistics, 2008 ISBN 9027231001, p. 30-31 [2]

- ↑ Viacheslav A. Chirikba, "The problem of the Caucasian Sprachbund" in Muysken, p. 74

- ↑ Lenore A. Grenoble, Language Policy in the Soviet Union, 2003 ISBN 1402012985,p. 131 [3]

- ↑ Persian Studies in North America by Mohammad Ali Jazayeri

External links

- Learning Azeri Site

- AZERI.org - Azerbaijan Literature and English translation

- Alphabet and Language in Transition. Entire issue of Azerbaijan International (AZER.com), Spring 2000 (8.1)

- Editorial: Azerbaijani Alphabet & Language in Transition. Azerbaijan International (AZER.com), Spring 2000 (8.1)

- Chart: Four Alphabet Changes in Azerbaijan in the 20th Century. Azerbaijan International (AZER.com), Spring 2000 (8.1)

- Chart: Changes in the Four Azerbaijan Alphabet Sequence in the 20th century. Azerbaijan International (AZER.com), Spring 2000 (8.1)

- Baku’s Institute of Manuscripts: _Early Alphabets in Azerbaijan__. Azerbaijan International (AZER.com), Spring 2000 (8.1)

- Azeri language at Ethnologue

- Azeri language, alphabets and pronunciation at omniglot.com

- Pre-Islamic roots

- Azerbaijani-Turkish language in Iran by Ahmad Kasravi

- Azeri with Japanese translation incl. sound file

- Azerbaijani-Turkish and Turkish-Azerbaijani dictionary

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||