Exergy

- "Available energy" redirects here. For the meaning of the term in particle collisions, see Available energy (particle collision).

In thermodynamics, the exergy of a system is the maximum work possible during a process that brings the system into equilibrium with a heat reservoir. When the surroundings are the reservoir, exergy is the potential of a system to cause a change as it achieves equilibrium with its environment. Exergy is then the energy that is available to be used. After the system and surroundings reach equilibrium, the exergy is zero.

Energy is never destroyed during a process; it changes from one form to another (See First Law of Thermodynamics). In contrast, exergy accounts for the irreversibility of a process due to increases in entropy (See Second Law of Thermodynamics). Exergy is always destroyed when a process involves a temperature change. This destruction is proportional to the entropy increase of the system together with its surroundings. The destroyed exergy has been called anergy. For an isothermal process, exergy and energy are interchangeable terms, and there is no anergy.

Exergy analysis is performed in the field of industrial ecology to use energy more efficiently. The term was coined by Zoran Rant in 1956, but the concept was developed by J. Willard Gibbs in 1873. Ecologists and design engineers often choose a reference state for the reservoir that may be different from the actual surroundings of the system.

Exergy is a co-property of a system and a reference state. Because of this, exergy is neither a thermodynamic property of matter nor a thermodynamic potential of a system. It is, however, the most useful application of these values, and is derivable from them mathematically. Determining exergy was also the first goal of thermodynamics. Exergy and energy both have units of joules. Both are also state functions even though work itself is not.

The term exergy is also used, by analogy with its physical definition, in information theory related to reversible computing. Exergy is also synonymous with: availability, available energy, exergic energy, essergy (considered archaic), utilizable energy, available useful work, maximum (or minimum) work, maximum (or minimum) work content, reversible work, and ideal work.

Contents |

History

Carnot

In 1824, Sadi Carnot studied the improvements developed for steam engines by James Watt and others. Carnot utilized a purely theoretical perspective for these engines and developed new ideas. He wrote:

- "The question has often been raised whether the motive power of heat is unbounded, whether the possible improvements in steam engines have an assignable limit—a limit by which the nature of things will not allow to be passed by any means whatever... In order to consider in the most general way the principle of the production of motion by heat, it must be considered independently of any mechanism or any particular agent. It is necessary to establish principles applicable not only to steam-engines but to all imaginable heat-engines... The production of motion in steam-engines is always accompanied by a circumstance on which we should fix our attention. This circumstance is the re-establishing of equilibrium... Imagine two bodies A and B, kept each at a constant temperature, that of A being higher than that of B. These two bodies, to which we can give or from which we can remove the heat without causing their temperatures to vary, exercise the functions of two unlimited reservoirs..."

Carnot next described what is now called the Carnot engine, and proved by a thought experiment that any heat engine performing better than this engine would be a perpetual motion machine. Even in the 1820s, there was a long history of science forbidding such devices. According to Carnot, "Such a creation is entirely contrary to ideas now accepted, to the laws of mechanics and of sound physics. It is inadmissible."[4]

This description of an upper bound to the work that may be done by an engine was the earliest modern formulation of the second law of thermodynamics. Because it involves no mathematics, it still often serves as the entry point for a modern understanding of both the second law and entropy. Carnot's focus on heat engines, equilibrium, and heat reservoirs is also the best entry point for understanding the closely related concept of exergy.

Carnot believed in the incorrect caloric theory of heat that was popular during his time, but his thought experiment nevertheless described a fundamental limit of nature. As kinetic theory replaced caloric theory through the early and mid-1800s (see timeline), several scientists added mathematical precision to the first and second laws of thermodynamics and developed the concept of entropy. Carnot's focus on processes at the human scale (above the thermodynamic limit) led to the most universally applicable concepts in physics. Entropy and the second-law are applied today in fields ranging from quantum mechanics to physical cosmology.

Gibbs

In the 1870s, Josiah Willard Gibbs unified a large quantity of 19th century thermochemistry into one compact theory. Gibbs's theory incorporated the new concept of a chemical potential to cause change when distant from a chemical equilibrium into the older work begun by Carnot in describing thermal and mechanical equilibrium and their potentials for change. Gibbs's unifying theory resulted in the thermodynamic potential state functions describing differences from thermodynamic equilibrium.

In 1873, Gibbs derived the mathematics of "available energy of the body and medium" into the form it has today.[3] (See the equations below). The physics describing exergy has changed little since that time. The term exergy was suggested in 1956 by Zoran Rant (1904–1972) by using the Greek ex and ergon meaning "from work."[2]

Mathematical description

An application of the second law of thermodynamics

- See Also: Second law of thermodynamics

Exergy uses system boundaries in a way that is unfamiliar to many. We imagine the presence of a Carnot engine between the system and its reference environment even though this engine does not exist in the real world. Its only purpose is to measure the results of a "what-if" scenario to represent the most efficient work interaction possible between the system and its surroundings.

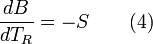

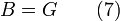

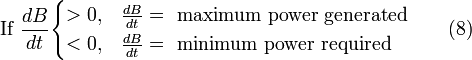

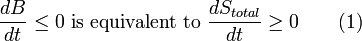

If a real-world reference environment is chosen that behaves like an unlimited reservoir that remains unaltered by the system, then Carnot's speculation about the consequences of a system heading towards equilibrium with time is addressed by two equivalent mathematical statements. B, the exergy or available work, will decrease with time, and Stotal, the entropy of the system and its reference environment enclosed together in a larger isolated system, will increase with time:

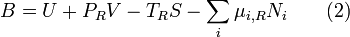

For macroscopic systems (above the thermodynamic limit), these statements are both expressions of the second law of thermodynamics if the following expression is used for exergy:

where the extensive quantities for the system are U = Internal energy, V = Volume, and Ni = Moles of component i. The intensive quantities for the surroundings are PR = Pressure and  = Chemical potential of component i. Individual terms also often have names attached to them:

= Chemical potential of component i. Individual terms also often have names attached to them:  is called "available PV work",

is called "available PV work",  is called "entropic loss" or "heat loss" and the final term is called "available chemical energy."

is called "entropic loss" or "heat loss" and the final term is called "available chemical energy."

Other thermodynamic potentials may be used to replace internal energy so long as proper care is taken in recognizing which natural variables correspond to which potential. For the recommended nomenclature of these potentials, see (Alberty, 2001). Equation (2) is useful for processes where system volume, entropy, and number of moles of various components change because internal energy is also a function of these variables and no others.

An alternative definition of internal energy does not separate available chemical potential from U. This expression is useful (when substituted into equation (1)) for processes where system volume and entropy change, but no chemical reaction occurs:

In this case a given set of chemicals at a given entropy and volume will have a single numerical value for this thermodynamic potential. A multi-state system may complicate or simplify the problem because the Gibbs phase rule predicts that intensive quantities will no longer be completely independent from each other.

A historical and cultural tangent

In 1848, William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin asked (and immediately answered) the question:

- Is there any principle on which an absolute thermometric scale can be founded? It appears to me that Carnot’s theory of the motive power of heat enables us to give an affirmative answer.

With the benefit of the hindsight contained in equation (3), we are able to understand the historical impact of Kelvin's idea on physics. Kelvin suggested that the best temperature scale would describe a constant ability for a unit of temperature in the surroundings to alter the available work from Carnot's engine. From equation (3):

Rudolf Clausius recognized the presence of a proportionality constant in Kelvin's analysis and gave it the name entropy in 1865 from the Greek for "transformation" because it describes the available energy lost during transformation from heat to work. The available work from a Carnot engine is at its maximum when the surroundings are at a temperature of absolute zero.

Physicists then, as now, often look at a property with the word "available" or "utilizable" in its name with a certain unease. The idea of what is available raises the question of "available to what?" and raises a concern about whether such a property is anthropocentric. Laws derived using such a property may not describe the universe but instead describe what people wish to see.

The field of statistical mechanics (beginning with the work of Ludwig Boltzmann in developing the Boltzmann equation) relieved many physicists of this concern. From this discipline, we now know that macroscopic properties may all be determined from properties on a microscopic scale where entropy is more "real" than temperature itself (see thermodynamic temperature). Microscopic kinetic fluctuations among particles cause entropic loss, and this energy is unavailable for work because these fluctuations occur randomly in all directions. The anthropocentric act is taken, in the eyes of some physicists and engineers today, when one draws a hypothetical boundary and in effect says, "This is my system. What occurs beyond it is surroundings." In this context, exergy is sometimes described as an anthropocentric property, both by those who use it and those who don't. Entropy is viewed as a more fundamental property of matter.

In the field of ecology, the interactions among systems (mostly ecosystems) and their manipulation of exergy resources is of primary concern. With this perspective, the answer to, "available to what?" is simply, "available to the system" because ecosystems appear to exist in the real world. With the viewpoint of systems ecology, a property of matter like absolute entropy is seen as anthropocentric because it is defined relative to an unobtainable hypothetical reference system in isolation at absolute zero temperature. With this emphasis on systems rather than matter, exergy is viewed as a more fundamental property of a system, and it is entropy that may be viewed as a co-property of a system with an idealized reference system.

A potential for every thermodynamic situation

In addition to  and

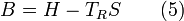

and ![U[\boldsymbol{\mu}]](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/89652baef97619f48f5316c131103e9f.png) , the other thermodynamic potentials are frequently used to determine exergy. For a given set of chemicals at a given entropy and pressure, enthalpy H is used in the expression:

, the other thermodynamic potentials are frequently used to determine exergy. For a given set of chemicals at a given entropy and pressure, enthalpy H is used in the expression:

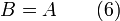

For a given set of chemicals at a given temperature and volume, Helmholtz free energy A is used in the expression:

For a given set of chemicals at a given temperature and pressure, Gibbs free energy G is used in the expression:

The potentials A and G are utilized for a constant temperature process. In these cases, all energy is free to perform useful work because there is no entropic loss. A chemical reaction that generates electricity with no associated change in temperature will also experience no entropic loss. (See fuel cell.) This is true of every isothermal process. Examples are gravitational potential energy, kinetic energy (on a macroscopic scale), solar energy, electrical energy, and many others. If friction, absorption, electrical resistance or a similar energy conversion takes place that releases heat, the impact of that heat on thermodynamic potentials must be considered, and it is this impact that decreases the available energy.

Applications

Applying equation (1) to a subsystem yields:

This expression applies equally well for theoretical ideals in a wide variety of applications: electrolysis (decrease in G), galvanic cells and fuel cells (increase in G), explosives (increase in A), heating and refrigeration (exchange of H), motors (decrease in U) and generators (increase in U).

Utilization of the exergy concept often requires careful consideration of the choice of reference environment because, as Carnot knew, unlimited reservoirs do not exist in the real world. A system may be maintained at a constant temperature to simulate an unlimited reservoir in the lab or in a factory, but those systems cannot then be isolated from a larger surrounding environment. However, with a proper choice of system boundaries, a reasonable constant reservoir can be imagined. A process sometimes must be compared to "the most realistic impossibility," and this invariably involves a certain amount of guesswork.

Engineering applications

Application of exergy to unit operations in chemical plants was partially responsible for the huge growth of the chemical industry during the 1900s. During this time it was usually called availability or available work.

As a simple example of exergy, air at atmospheric conditions of temperature, pressure, and composition contains energy but no exergy when it is chosen as the thermodynamic reference state known as ambient. Individual processes on Earth like combustion in a power plant often eventually result in products that are incorporated into a large atmosphere, so defining this reference state for exergy is useful even though the atmosphere itself is not at equilibrium and is full of long and short term variations.

If standard ambient conditions are used for calculations during plant operation when the actual weather is very cold or hot, then certain parts of a chemical plant might seem to have an exergy efficiency of greater than 100% and appear on paper to be a perpetual motion machine! Using actual conditions will give actual values, but standard ambient conditions are useful for initial design calculations.

One goal of energy and exergy methods in engineering is to compute balances between what comes into and out of several possible designs before a factory is built. After the balances are completed, the engineer will often want to select the most efficient process. An energy efficiency or first law efficiency will determine the most efficient process based on losing as little energy as possible relative to energy inputs. An exergy efficiency or second-law efficiency will determine the most efficient process based on losing and destroying as little available work as possible from a given input of available work.

Design engineers have recognized that a higher exergy efficiency involves building a more expensive plant, and a balance between capital investment and operating efficiency must be determined in the context of economic competition.

Applications in natural resource utilization

In recent decades, utilization of exergy has spread outside of physics and engineering to the fields of industrial ecology, ecological economics, systems ecology, and energetics. Defining where one field ends and the next begins is a matter of semantics, but applications of exergy can be placed into rigid categories.

Researchers in ecological economics and environmental accounting perform exergy-cost analyses in order to evaluate the impact of human activity on the current natural environment. As with ambient air, this often requires the unrealistic substitution of properties from a natural environment in place of the reference state environment of Carnot. For example, ecologists and others have developed reference conditions for the ocean and for the Earth's crust. Exergy values for human activity using this information can be useful for comparing policy alternatives based on the efficiency of utilizing natural resources to perform work. Typical questions that may be answered are:

- Does the human production of one unit of an economic good by method A utilize more of a resource's exergy than by method B?

- Does the human production of economic good A utilize more of a resource's exergy than the producution of good B?

- Does the human production of economic good A utilize a resource's exergy more efficiently than the production of good B?

There has been some progress in standardizing and applying these methods.

Applications in sustainability

In systems ecology, researchers sometimes consider the exergy of the current formation of natural resources from a small number of exergy inputs (usually solar radiation, tidal forces, and geothermal heat). This application not only requires assumptions about reference states, but it also requires assumptions about the real environments of the past that might have been close to those reference states. Can we decide which is the most "realistic impossibility" over such a long period of time when we are only speculating about the reality?

For instance, comparing oil exergy to coal exergy using a common reference state would require geothermal exergy inputs to describe the transition from biological material to fossil fuels during millions of years in the Earth's crust, and solar radiation exergy inputs to describe the material's history before then when it was part of the biosphere. This would need to be carried out mathematically backwards through time, to a presumed era when the oil and coal could be assumed to be receiving the same exergy inputs from these sources. A speculation about a past environment is different from assigning a reference state with respect to known environments today. Reasonable guesses about real ancient environments may be made, but they are untestable guesses, and so some regard this application as pseudoscience or pseudo-engineering.

The field describes this accumulated exergy in a natural resource over time as embodied energy with units of the "embodied joule" or "emjoule".

The important application of this research is to address sustainability issues in a quantitative fashion through a sustainability metric:

- Does the human production of an economic good deplete the exergy of Earth's natural resources more quickly than those resources are able to receive exergy?

- If so, how does this compare to the depletion caused by producing the same good (or a different one) using a different set of natural resources?

Assigning one thermodynamically obtained value to an economic good

A technique proposed by systems ecologists is to consolidate the three exergy inputs described in the last section into the single exergy input of solar radiation, and to express the total input of exergy into an economic good as a solar embodied joule or sej. (See emergy) Exergy inputs from solar ^ , tidal, and geothermal forces all at one time had their origins at the beginning of the solar system under conditions which could be chosen as an initial reference state, and other speculative reference states could in theory be traced back to that time. With this tool we would be able to answer:

- What fraction of the total human depletion of the Earth's exergy is caused by the production of a particular economic good?

- What fraction of the total human and non-human depletion of the Earth's exergy is caused by the production of a particular economic good?

No additional thermodynamic laws are required for this idea, and the principles of energetics may confuse many issues for those outside the field. The combination of untestable hypotheses, unfamiliar jargon that contradicts accepted jargon, intense advocacy among its supporters, and some degree of isolation from other disciplines have contributed to this protoscience being regarded by many as a pseudoscience. However, its basic tenets are only a further utilization of the exergy concept.

Implications in the development of complex physical systems

A common hypothesis in systems ecology is that the design engineer's observation that a greater capital investment is needed to create a process with increased exergy efficiency is actually the economic result of a fundamental law of nature. By this view, exergy is the analogue of economic currency in the natural world. The analogy to capital investment is the accumulation of exergy into a system over long periods of time resulting in embodied energy. The analogy of capital investment resulting in a factory with high exergy efficiency is an increase in natural organizational structures with high exergy efficiency. (See maximum power). Researchers in these fields describe biological evolution in terms of increases in organism complexity due to the requirement for increased exergy efficiency because of competition for limited sources of exergy.

Some biologists have a similar hypothesis. A biological system (or a chemical plant) with a number of intermediate compartments and intermediate reactions is more efficient because the process is divided up into many small substeps, and this is closer to the reversible ideal of an infinite number of infinitesimal substeps. Of course, an excessively large number of intermediate compartments comes at a capital cost that may be too high.

Testing this idea in living organisms or ecosystems is impossible for all practical purposes because of the large time scales and small exergy inputs involved for changes to take place. However, if this idea is correct, it would not be a new fundamental law of nature. It would simply be living systems and ecosystems maximizing their exergy efficiency by utilizing laws of thermodynamics developed in the 19th century.

Philosophical and cosmological implications

Some proponents of utilizing exergy concepts describe them as a biocentric or ecocentric alternative for terms like quality and value. The "deep ecology" movement views economic usage of these terms as an anthropocentric philosophy which should be discarded. A possible universal thermodynamic concept of value or utility appeals to those with an interest in monism.

For some, the end result of this line of thinking about tracking exergy into the deep past is a restatement of the cosmological argument that the universe was once at equilibrium and an input of exergy from some First Cause created a universe full of available work. Current science is unable to describe the first 10–43 seconds of the universe (See Timeline of the Big Bang). An external reference state is not able to be defined for such an event, and (regardless of its merits), such an arguments may be better expressed in terms of entropy.

Comparison of energy and exergy

Based on .

| The energy change of a process is... | The exergy change of a process is... |

|---|---|

| its ability to produce motion | its ability to produce work |

| conserved by the first law of thermodynamics | only conserved for reversible processes and destroyed by irreversible processes |

| different from zero (E=mc²) | equal to zero when at equilibrium with the environment |

| independent of environment parameters | dependent on environment parameters |

| limited by the second law of thermodynamics for all processes | unlimited for reversible processes due to the second law |

| a measure of quantity only | a measure of quantity and efficiency of utilization |

Exergy is a measurable value that is decreased during the conversion of useful energy to useless energy. Therefore, exergy measures the actual potential of a system to do work. The exergy consumed to create something, a product or service, is more than the work done to create it. Exergy is the work that can no longer be done elsewhere because the economic good was made. Exergy has been described as a measure of energy quality because of these traits.

Exergy is highly multidisciplinary

(This section will probably be shortened and added to the "Utilization" section as a table if possible) The cumulative exergy consumption of a good is a sum of the exergy decreases that occurred in order to create it. An initial state for an analysis might consist of exergy contributions from:

- 1) the material entering individual reactors or other unit

- 2) the material delivered to the industry and used for all the units in the industrial process.

- 3) the material purchased from other industries and all the associated indirect exergy decreases involved in transport and administration to get the material and process it.

- 4) all the initial natural resources used directly or indirectly to make the good.

- 5) all the initial ecological inputs (such as solar radiation, tidal forces, and geothermal heat) that created the natural resources.

- 6) These multiple inputs related to a single reference input (such as solar radiation).

- 7) This reference input is related to a single input of exergy to the universe from some external source at a time in the past when the entire universe was at equilibrium.

Choice 1 (if there are few components) is a tricky undergraduate homework problem in chemical engineering if a chemical reaction occurs in an open system. The worked example above utilizes choice 1 for a closed system with no reaction.

Choice 2 would require an in-house exergy accounting analogous to a process mass balance or energy balance. If there are a reasonable number of unit operations, a professional chemical engineer could do this in a short period of time with a good software package to determine exergy flows in the plant.

Choice 3 would require all of choice 2 and converting multiple items usually thought of as economic overhead into terms of exergy. This could be a challenging task requiring considerable thought, but with several assumptions here and there (and more software to keep track of the accounting), it could be done.

Choice 4 would require a repetition of choice 3 for multiple industries, governmental agencies, and all other human activity to convert raw materials to the product. It seems unlikely that many producers would take the time to determine the complete exergy history of their product, but if we ever live in a world where producers were required to perform choice 3, we might be able to get a reasonable estimate of choice 4.

Choice 5 in combination with choice 4 is the only option that is relevant to environmental sustainability. Choice 5 requires exergy information from the field of systems ecology and many additional assumptions. However, with this information, we may address the questions:

- Does the human production of this item deplete the Earth's natural resources more quickly than those resources are able to regenerate themselves?

- If so, how does this numerically compare to the depletion caused by producing an entirely different item using an entirely different set of natural resources?

Choice 6 represents all exergy changes on Earth in terms of one "currency" that may be used to estimate the relative value of different natural resources, but this value appraisal would not be on a time scale relevant to human activity. Choice 6 is useful for systems ecologists to consider exergy concepts as a driving force for the emergence structures in nature using a concept like emergy.

Choice 7 is the consequence of this line of thinking carried out to its fullest extent. It is a thought experiment to restate the cosmological argument.

Quality of energy types

(exergy-to-energy ratio will be in this article. exergy-to-exergy will be moved to Exergy efficiency. Some will be removed.)

The ratio of exergy to energy in a substance can be considered a measure of energy quality. Forms of energy such as macroscopic kinetic energy, electrical energy, and chemical Gibbs free energy are 100% recoverable as work, and therefore have an exergy equal to their energy. However, forms of energy such as radiation and thermal energy can not be converted completely to work, and have exergy content less than their energy content. The exact proportion of exergy in a substance depends on the amount of entropy relative to the surrounding environment as determined by the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

Exergy is useful when measuring the efficiency of an energy conversion process. The exergetic, or 2nd Law efficiency, is a ratio of the exergy output divided by the exergy input. This formulation takes into account the quality of the energy, often offering a more accurate and useful analysis than efficiency estimates only using the First Law of Thermodynamics.

Work can be extracted also from bodies colder than the surroundings. When the flow of energy is coming into the body, work is performed by this energy obtained from the large reservoir, the surrounding. A quantitative treatment of the notion of energy quality rests on the definition of energy. According to the standard definition, Energy is a measure of the ability to do work. Work can involve the movement of a mass by a force that results from a transformation of energy. If there is an energy transformation, the second principle of energy flow transformations says that this process must involve the dissipation of some energy as heat. Measuring the amount of heat released is one way of quantifying the energy, or ability to do work and apply a force over a distance.

However, it appears that the ability to do work is relative to the energy transforming mechanism that applies a force. This is to say that some forms of energy perform no work with respects to some mechanisms, but perform work with respects to others. For example, water does not have a propensity to combust in an internal combustion engine, whereas gasoline does. Relative to the internal combustion engine, water has little ability to do work that provides a motive force. If “energy” is defined as the ability to do work then a consequence of this simple example is that water has no energy — according to this definition. Nevertheless, water, raised to a height, does have the ability to do work like driving a turbine, and so does have energy.

This example means to demonstrate that the ability to do work can be considered relative to the mechanism that transforms energy, and through such a conversion applies a force. From this observation we might wish to use the word “quality”, and the term “energy quality” to characterise the energetic differences between substances and their propensities to perform work given a specific mechanism. That is the abilities of different energy forms to flow and be transformed in certain mechanisms. With this lexicon, we can say that energy quality is mechanism-relative, and the energy efficiency of a mechanism is energy quality-relative – an internal combustion engine running on water has nearly 0% efficiency since it has the propensity to transform little or no water-energy into thermal-energy. In order to clarify things here we might think of this as the “water-efficiency”. The mechanism of interest is also our system of reference, such that the choice of energy quality specifies a certain system of reference. Thus with respects to the internal combustion system of reference, it has a low “water-efficiency”.

Exergy of heat available at a temperature

Maximal possible conversion of heat to work, or exergy content of heat, depends on the temperature at which heat is available and the temperature level at which the reject heat can be disposed, that is the temperature of the surrounding. The upper limit for conversion is known as Carnot efficiency and was discovered by Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot in 1824. See also Carnot heat engine.

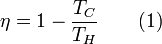

Carnot efficiency is

where TH is the higher temperature and TC is the lower temperature, both as absolute temperature. From Equation 1 it is clear that in order to maximize efficiency one should maximize TH and minimize TC.

For calculation of exergy of heat available at a temperature there are two cases: the body releasing heat is higher than the surrounding, or, the temperature of the body is lower than the surrounding.

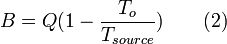

Exergy exchanged is then:

where Tsource is the temperature of the heat source, and To is the temperature of the surrounding.

See also

References

- ^ Perrot, Pierre (1998). A to Z of Thermodynamics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-856552-6.

- ^ "lowexnet".

- ^ a Z. Rant (1956). "Exergie, ein neues Wort fur "Technische Arbeitsfahigkeit" (Exergy, a new word for "technical available work")". Forschung auf dem Gebiete des Ingenieurwesens 22: 36–37.

- ^ a J.W. Gibbs (1873). "A method of geometrical representation of thermodynamic properties of substances by means of surfaces: repreinted in Gibbs, Collected Works, ed. W. R. Longley and R. G. Van Name (New York: Longmans, Green, 1931)". Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences 2: 382–404.

- ^ a S. Carnot (1824). Réflexions sur la puissance motrice du feu sur les machines propres a developper cette puissance. (Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire and on Machines Fitted to Develop That Power. Translated and edited by R.H. Thurston 1890). Paris: Bachelier. http://www.history.rochester.edu/steam/carnot/1943/Section2.htm.

- ^ Alberty, R. A. (2001). "Use of Legendre transforms in chemical thermodynamics". Pure Appl. Chem. 73 (8): 1349–1380. doi:. http://www.iupac.org/publications/pac/2001/pdf/7308x1349.pdf.

- ^ Lord Kelvin (William Thomson) (1848). "On an Absolute Thermometric Scale founded on Carnot's Theory of the Motive Power of Heat, and calculated from Regnault's Observations". Philosophical Magazine [from Sir William Thomson, Mathematical and Physical Papers, vol. 1 (Cambridge University Press, 1882), pp. 100–106.]. http://zapatopi.net/kelvin/papers/on_an_absolute_thermometric_scale.html.

- ^ a I. Dincer, Y.A. Cengel (2001). "Energy, entropy, and exergy concepts and their roles in thermal engineering". Entropy 3: 116–149. http://www.mdpi.org/entropy/papers/e3030116.pdf.

- ^ San, J. Y., Lavan, Z., Worek, W. M., Jean-Baptiste Monnier, Franta, G. E., Haggard, K., Glenn, B. H., Kolar, W. A., Howell, J. R. (1982). "Exergy analysis of solar powered desiccant cooling system". Proc. of the American Section of the Intern. Solar Energy Society: 567–572.

- S.Bastianoni, A. Facchini, L. Susani, E. Tiezzi (2007) 'Emergy as a function of exergy', Energy 32, 1158–1162.

External links

Exergy and Rankine cycle - http://twt.mpei.ac.ru/MAS/Worksheets/Rankine3D.mcd

- MIT Open Courseware 10-391J (ChemE Dept.-Sustainable Energy course) Spring 2005

- MIT Open Courseware 10-391J (ChemE Dept.-Sustainable Energy course) Spring 2005 Thermodynamics and Efficiency Analysis (Toolbox 6)

- Energy, Incorporating Exergy, An International Journal

- An Annotated Bibliography of Exergy/Availability

- Exergy - a useful concept by Göran Wall

- Exergy by Isidoro Martinez

- Exergy: Energy and the Second Law by Wes Hermann

- Exergy calculator by The Exergoecology Portal

![B=U[\mu_1, \mu_2, ... \mu_n] +P_RV -T_RS=U[\boldsymbol{\mu}] +P_RV -T_RS \qquad \mbox{(3)}](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/3b8bece80de34a264f4ea42e5b9d95d4.png)