Autobahn

Autobahn (German: IPA: [ˈaʊtoːbaːn], plural Autobahnen; English: /ˈɔːtəʊbɑːn/) is the German word for a major high-speed road restricted to motor vehicles capable of driving at least 60 km/h (37 mph) and having full control of access, similar to a motorway or freeway in English-speaking countries.

In most countries, it usually refers to the German autobahn specifically. The recommended speed of the German autobahn is 130 km/h (81 mph), but there is no general speed limit. Austrian and Swiss autobahns have general speed limits of 130 km/h (81 mph) and 120 km/h (75 mph), respectively. In German, the word is pronounced as described above, and its plural is Autobahnen; in English, however, the segment "auto" is typically pronounced as in other English words such as "automobile". The official name of the autobahn in Germany is Bundesautobahn (BAB) (Federal Freeway). Autobahns are built and maintained by the federal government (as are the federal highways), thus the name "Federal Freeway". The first were built in the 1920s, and in the 1930s the official name was "Reichsautobahn" (Freeways of the Reich).

Contents |

Construction

Germany

Just like all European highways, autobahns have multiple lanes of traffic in each direction, separated by a central barrier with grade-separated junctions and access restricted to certain types of motor vehicles only. The first road of this kind was completed in 1931 between Cologne and Bonn and opened by Konrad Adenauer (Lord Mayor of Cologne and future Chancellor of West Germany) on 6 August 1932.[1] This road was not yet called Autobahn, but instead was known as a Kraftfahrtstraße (lit. automobile road). The idea was a street which had no crossings and was only to be used by cars and motorcycles and not by pedestrians or the common horse drawn carts. As Adolf Hitler did not become Chancellor until afterwards in January 1933, the claim that the Autobahn was conceived by the Nazis is a myth.[2]

Nevertheless, for a variety of reasons, the Nazi regime pressed ahead with the construction of the Autobahn system. This created jobs and reduced the unemployment rate, though slave labour was used at this time. The Autobahn also possibly served another purpose: the road connection between various regions within Germany could make military defense and logistics much more efficient and rapid in response. In addition, with the availability of road access, Germans could now easily travel (and relocate) to various regions within Germany, thus weakening regional differences and (in the long run) bringing about a more singular popular vision of a united Germany.

Each Reichsautobahn carriageway was flanked by banquettes about 60 cm in width, constructed of varying materials; right-hand banquettes on many autobahns were later retrofitted to 120 cm in width when it was realized cars needed the additional space to pull off the autobahn safely. In the postwar years, a thicker asphalt concrete cross-section with full paved hard shoulders came into general use. The maximum design speed was approximately 80 km/h in flat country but lower design speeds could be used in hilly or mountainous terrain. A flat-country autobahn constructed to published design standards in use during the Nazi period could support hands-off (banking of the roadway where the car would track straight, despite the curvature of the road) speeds on curves of about 40 km/h.

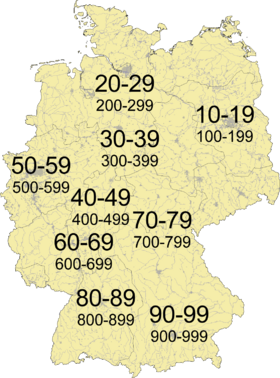

The current Bundesautobahn numbering system was introduced in West Germany in 1974. After the reunification of East and West Germany in 1990, the Deutsche Einheit Fernstraßenplanungs- und -bau GmbH (DEGES) was founded to coordinate necessary construction work in the new Länder. All Autobahns are named by using the capital letter A followed by a space and a number (for example A 8). The "main autobahns" going all across Germany have a single digit number usually even-numbered for east-west routes and odd-numbered for north-south routes. Shorter autobahns that are of regional importance (e.g. connecting two major cities or regions within Germany) have a double digit number (e.g. A 24, connecting Berlin and Hamburg). The system is as follows:

- A 10 to A 19 are in eastern Germany (Berlin, Saxony-Anhalt, parts of Saxony and Brandenburg)

- A 20 to A 29 in northern and northeastern Germany

- A 30 to A 39 in Lower Saxony and North-Rhine-Westphalia (northwestern Germany)

- A 40 to A 49 in the Rhine-Ruhr Area

- A 50 to A 59 also in the Rhine-Ruhr Area

- A 60 to A 69 in Rhineland-Palatinate, Saarland and Hessen

- A 70 to A 79 in Thuringia, northern Bavaria and parts of Saxony

- A 80 to A 89 in Baden-Württemberg

- A 90 to A 99 in (southern) Bavaria

There are also very short autobahns, of local importance (such as beltways, or the A 555 from Cologne to Bonn). These usually have three numbers, the first one of which is similar to the system above, depending on the region.

The North-South Autobahnen are odd-numbered, the East-West ones are even-numbered.

Switzerland

In Switzerland, it is impractical to navigate using the autobahn numbers; instead it is useful to steer toward the largest city that lies in the intended target region; this is because traffic signs display the city names much more prominently than in Germany. In Switzerland, exits occur with greater frequency than in the other two.

History

Germany

The idea for the construction of the autobahn was first conceived during the days of the Weimar Republic, but apart from the AVUS in Berlin, construction was slow, and most projected sections did not progress much beyond the planning stage due to economic problems and a lack of political support. One project was the private initiative HaFraBa which planned a "car-only road" (the name autobahn was created in 1929) crossing Germany from Hamburg in the North via central Frankfurt am Main to Basel in Switzerland. Parts of the HaFraBa were completed in the 1930s and early 1940s, but construction eventually was halted by World War II.

Upon assuming power in January 1933, Adolf Hitler enthusiastically embraced an ambitious autobahn construction project. On 27 June 1933, the Reich government (Reichsregierung) enacted the "Law on the Establishment of a 'Reichsautobahn' Enterprise" (Gesetz über die Errichtung eines Unternehmens "Reichsautobahnen").[3] In accordance with Section 5 of this law, Hitler appointed Fritz Todt as Inspector General of German Roads (Generalinspektor für das deutsche Straßenwesen). Soon, over 100,000 laborers worked at construction sites all over Germany. Sections 1 and 5 of the same law assigned responsibility for the oversight of the "Reichsautobahn" enterprise to the German railway company, the Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft (DRG). However, this arrangement was terminated on 23 January 1935 by a decree transferring control of the enterprise to Todt, on the grounds that the DRG had not given the necessary priority to the project.[4]

As well as providing employment and improved infrastructure, necessary for economic recovery efforts, the project was also a great success for propaganda purposes. It has been said that another aim of the autobahn project, beyond creating national unity and strengthening centralized rule, was to provide mobility for the movement of military forces. This, however, overlooks the fact that gradients on autobahns built before the war were far too steep for the goods vehicles of the time. The autobahn's main purpose, then, was to enable a large proportion of the population to drive long distances in their own cars, enjoying the countryside along the way. This explains some of the autobahn's routing (as at Irschenberg on the A 8 from Munich to Salzburg) which offers spectacular views but is impractical for today's heavy goods traffic (see Nazi architecture).

The autobahns formed the first limited-access, high-speed road network in the world, with the first section from Frankfurt am Main to Darmstadt opening in 1935. This straight section was used for high speed record attempts by the Grand Prix racing teams of Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union until a fatal accident involving popular German race driver Bernd Rosemeyer in early 1938. A similar high speed section was built between Dessau and Halle.

During World War II, the central reservation of some autobahns were paved to allow their conversion into auxiliary airports. Aircraft were either concealed in numerous tunnels or camouflaged in nearby woods. However, for the most part, the autobahns were not militarily significant. Motor vehicles could not carry goods as quickly or in as much bulk as trains could, and the autobahns could not be used by tanks as their weight and caterpillar tracks tore up the roads' delicate surfaces. Furthermore, the general shortage of gasoline which Germany experienced during much of the war, as well as the relatively low number of trucks and motor vehicles badly needed for direct support of military operations, further decreased the attractiveness of autobahns for significant transport. As a result, most military and economic freight continued to be carried by rail. After the war, numerous sections of the autobahns were in bad shape, severely damaged by heavy Allied bombing and military demolition. As well, thousands of kilometers of autobahns remained unfinished, their construction brought to a halt by 1943 due to the increasing demands of the war effort.

In West Germany, following the war, most existing autobahns were soon repaired. During the 1950s, the West German government restarted the construction program; it continuously invested in new sections and in improvements to older ones. The finishing of the incomplete sections took longer, with some stretches being opened to traffic only in the 1980s. Some sections cut by the Iron Curtain in 1945 were only completed after German reunification in 1990. Finally, certain sections were never completed, as more advantageous routes were found. Some of these sections stretch across the landscape forming a unique type of modern ruin, often easily visible on satellite photographs.

The autobahns in East Germany (GDR) and the former German provinces of East Prussia, eastern Pomerania and Silesia in Poland and the Soviet Union after 1945 were grossly neglected in comparison to those in West Germany and Western Europe in general. They received minimal maintenance during the years of the Cold War. In many places only one side of the carriageway is driveable, while the other had never received any maintenance since 1943. The speed limit on the GDR autobahns was 100 km/h, however lower speed limits were frequently encountered due to the poor condition of the road surface, changing quickly in some instances. The speed limits on the GDR autobahns were rigorously enforced by the Volkspolizei, whose patrol cars were frequently encountered hiding under camouflage waiting for speeders. In the 1970s and 80s, the West German government paid millions of Deutsche Marks to the GDR for construction and maintenance of the transit autobahns between West Germany and West Berlin, although there were indications that the GDR diverted some of the earmarked maintenance funds for other purposes.

Switzerland

A short stretch of autobahn around the Lucerne area in 1955 created Switzerland's first autobahn. For Expo 1964, an autobahn was built between Lausanne and Geneva. The Bern-Lenzburg route was inaugurated in 1967.

Current density

Germany

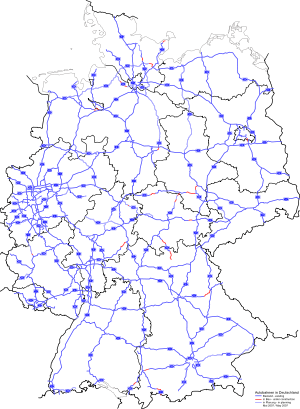

Today, Germany's autobahn network has a total length of about 12,200 km (in 2005), which ranks as the third-longest in the world behind the Interstate Highway System of the United States and the National Trunk Highway System (NTHS) of the People's Republic of China. Most sections of older German autobahns have been modernized and today a large amount of them (roughly a third) contain three lanes or more in addition to an emergency lane.

Switzerland

The Swiss autobahn network has a total length of 1,638 km (as of 2000) and has, by an area of 41,290 km², also the one of the highest highway densities in the world. The Swiss autobahn network has not yet been completed; priority has been given to the most important routes, especially the north-south and the east-west axes. The gaps in the autobahn network are apparent in the graphic. Swiss autobahns usually have an emergency lane, except in tunnels. Some newly built autobahn sections, like the lone section crossing the Jura region in the north-western part of Switzerland, only have emergency bays.

Speed limits

A hard limit is imposed on some vehicles:

| 60 km/h |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 80 km/h |

|

|

| 100 km/h |

|

|

| 145 km/h |

|

Germany

The German autobahns are famous for being some of the few public roads in the world without blanket speed limits for cars and motorcycles. Certainly, speed limits do apply at junctions and other danger points, like sections under construction or in need of repair. Speed limits at non-construction sites are typically 100 km/h, 120 km/h, or 130 km/h, on the A2 are also parts with a 140 km/h speed limit. Construction sites have a usual speed limit of 80 km/h but may be as low as 60 km/h or even 40 km/h. Certain stretches have separate, and lower, speed limits used in cases of wet lanes. These stretches often feature an electronic speed limit signal that utilises monitors mounted above the roadway. For example, if weather conditions worsen on a stretch of autobahn, the monitors above the roadway may signal a temporary speed limit.

Some limits were imposed to reduce pollution and noise. Limits can also be put into place temporarily through dynamic traffic guidance systems that display the according traffic signs. If there is no speed limit, the recommended speed limit is 130 km/h, referred to in German as the Richtgeschwindigkeit; this speed is not a binding limit, but being involved in an accident at higher speeds can lead to being deemed at least partially responsible due to "increased operating danger" (Erhöhte Betriebsgefahr). The average speed traveled on the autobahn in unregulated areas by automobiles not regulated by other laws is about 150 km/h. On average, about three quarters of the total length of the German autobahn network has no speed limit, about one quarter has a permanent limit, and the remaining parts have a temporary limit for a number of reasons.

In places without a general limit, there are mostly also no restrictions on overtaking, except for the Rechtsfahrgebot, a rule that requires drivers to use the right lane if possible and only pass other cars on their left, except when heavy traffic does not permit this. Therefore, those traveling at high speeds may regularly encounter trucks running side-by-side at only about 80 km/h. In theory, trucks are not allowed to overtake others unless they drive 20 km/h faster than whomever they are overtaking, but truck drivers are generally under pressure to arrive in time, and such laws are rarely enforced for economic and political reasons, as many trucks are from foreign countries. The right lane of a typical autobahn is often crowded with trucks, and often, trucks pull out to overtake. Due to size and speed this is often referred to as 'Elefantenrennen' (Elephant Race). In some zones with only two lanes in both directions there is no speed limit, but a special overtaking restriction for trucks and/or cars pulling trailers. (An exception is Sundays, on which trucks usually are not allowed to drive, except for trucks with perishable goods and certain other exceptions.)

Many modern cars are capable of speeds of over 230 km/h, and most large manufacturers of luxury cars follow a gentlemen's agreement by technically limiting the top speed of their cars to 250 km/h for safety reasons (inexperienced drivers and risk of tire failure, especially when underinflated). Yet, these limiters can easily be removed on request at the relevant manufacturer's dealership with an electronic diagnosis device, so speeds exceeding 300 km/h are not unheard of, although due to other traffic, such speeds are rarely attainable.

Vehicles unable to attain speeds in excess of 60 km/h are not allowed to use the autobahn. Though this limit is not high for most modern vehicles, it prevents very small cars (e.g. Quads) and motor-scooters (e.g. mopeds) from using autobahns. To comply with this limit, several heavy-duty trucks (e.g. for carrying heavy equipment) have a design speed of 62 km/h (usually denoted by a round black-on-white sign with "62" on it).

Accident record

The overall safety record of German autobahns is generally better than other European highways. German autobahn fatality rates are lower than Austria's and higher than Switzerland's rates. Highways are safer than other road types, as documented below.

| Rate = Killed per 1 Billion Veh·km [5] | |||||||

| Autobahn | Other Roads | Total | Autobahn | Other Roads | Total | Autobahn | |

| YEAR | Fatalities[3] | Fatalities | Fatalities | Death Rate[4] | Death Rate | Death Rate | (% of Road Travel) |

| 1970 | 945 | 18,248 | 19,193 | 27.0 | 84.5 | 76.5 | 14 |

| 1980 | 804 | 12,237 | 13,041 | 10.0 | 42.6 | 35.4 | 22 |

| 1985 | 669 | 7,731 | 8,400 | 7.1 | 26.7 | 21.9 | 25 |

| 1990[6] | 936 | 6,970 | 7,906 | 6.9 | 19.8 | 16.2 | 28 |

| 1995 | 978 | 8,476 | 9,454 | 5.5 | 19.0 | 15.1 | 29 |

| 2000 | 907 | 6,596 | 7,503 | 4.5 | 14.3 | 11.3 | 31 |

| 2005 | 662 | 4,699 | 5,361 | 3.0 | 10.0 | 7.8 | 31 |

A 2005 study by the German Federal Interior Ministry (Bundesministerium des Innern) indicated that Autobahn sections with unrestricted speed have the same accident record as sections with speed limits. The only identifiable source of traffic risks in connection with speeding have been high-powered, light trucks that came up within the last 15 years and as they are used by courier services (e.g. Mercedes-Benz Sprinter and trucks alike). Over the years they were only capable of speeds comparable to heavy duty trucks, but since manufacturers began to build in significantly more powerful engines they attain speeds of up to 180 km/h. This led to a significant portion of fatal accidents being caused by such vehicles [7] due to the driver overestimating his or the car's ability to cope with sudden and heavy braking, side-winds, etc.

Public debate

Since the mid-1980s, when environmental issues gained importance and recognition among lawmakers, interest groups and the general public, there has been an ongoing debate on whether or not a general speed limit should be imposed for all Autobahns. A car's fuel consumption increases with speed, and fuel conservation is a key factor in reducing air pollution. Safety issues have been cited as well with regards to speed-related fatalities. Those opposed to a general speed limit maintain that such regulation is unnecessary because only two percent of all roads in Germany would be affected and because better fuel economy even at high speeds has been achieved in most modern cars. Moreover, international accident statistics demonstrate that Autobahn-like roads have a superior safety record, regardless of speed limit. Another reason is that the German cars have a high speed image and so the car lobby (VDA, AVD, ADAC, Porsche, Mercedes, Audi, BMW, Volkswagen, Opel, etc.) is against a speed limit.

In the discussion about such plans during his political term of office, the former Bundeskanzler Gerhard Schröder called Germany an "Autofahrernation" (a nation of drivers) to point out the fact that a speed limit would not be generally accepted by the public.

Over twenty years after the beginning of this debate, there are still no definite plans by the German government concerning such a speed limit. In October 2007, at a party congress held by the SPD, one of Germany's governing parties, delegates narrowly approved a proposal to introduce a blanket speed limit of 130 km/h (80 mph) on all German Autobahns. While this initiative is primarily a part of the SPD's general strategic outline for the near future and according to practices not necessarily meant to affect immediate government policy, the proposal stirred up a renewed debate about the pros and cons of such a measure. Germany's chancellor Angela Merkel and leading cabinet members have expressed outspoken disapproval; polls conducted in the wake of the proposal, however, showed the country deeply divided on the issue, with figures either putting approval or rejection scantly above the 50 percent mark.

Toll requirements

Germany

A recent development involves the introduction of mandatory tolls (Mautpflicht) for heavy trucks (weighing 12 t or more) on January 1, 2005. The German government contracted a private company, Toll Collect GmbH to operate the toll collection system, which involves the use of vehicle-mounted transponders and roadway-mounted sensors installed throughout Germany. The introduction of this system experienced several technical delays resulting in the loss of millions of Euros in potential revenue to the government. One result of the new toll policy has been an increase in heavy truck traffic on regular highways (Bundesstraßen and Landstraßen) in order to avoid paying tolls. There have been recent discussions about extending the toll requirement to include passenger cars, however this has proven so far to be very unpopular with a majority of the public. Politicians of the major parties have denied they are considering such measures.

Austria and Switzerland

Both the Swiss and Austrian autobahn systems require the purchase of a vignette (toll sticker) for passenger cars in order to use their respective roadways. But there is also the possibility of some routes where you have to pay an extra toll in case of more expensive cost of preservation by the autobahn-company (e.g. tunnels or high alpine autobahns). The Swiss vignette is offered only as an annual toll sticker, while the Austrians offer their vignettes in varying lengths of validity (10 days, 2 months or a year).

Since 2005 trucks travelling on Austrian autobahns are required to have a Go-Box, a small white box which counts the length of the used autobahn with electrical control points. The Go-Box is queried by overhead DSRC microwave radio transceivers at each exit. As only trucks need to carry a Go-Box, overhead 3-D infrared laser scanners are used to detect and photograph trucks without Go-Box.

In Switzerland a similar system is in use, using a box called "Tripon". Different from Austria and Germany, trucks are obligated to pay toll (Leistungsabhängige Schwerverkehrsabgabe (LSVA) (Power-dependent heavy traffic toll)) for every use of Swiss roads (also on regular highways and local roads).

Traffic laws and enforcement

The German autobahn network is patrolled by the Autobahnpolizei (Autobahn police) in marked and unmarked police vehicles, some equipped with video cameras. This practice allows the enforcement of laws (tailgating, for example) which are often viewed in other countries as difficult to prove in court. Notable laws include the following:

- Autobahns in Austria and Germany may only be used by motor vehicles that are designed to achieve a maximum speed exceeding 60 km/h (Switzerland: 80 km/h).

- The right lane must be used when it is free, (Rechtsfahrgebot) and the left lane is generally intended for passing manoeuvres only. Drivers using the left lane when the other lanes are free may be fined by autobahn police.

- Overtaking on the right (undertaking) is forbidden, except in traffic jams where it may be practiced with caution. The fact that the car overtaken is illegally occupying the left-hand lane is not an acceptable excuse. In these cases the police will routinely stop and fine both drivers.

- Not allowing faster cars to overtake one's own car if the traffic situation allows it (e.g. by occupying the left-hand lane for a longer period of time) may be considered coercion[8].

- In case of a traffic jam, the drivers must form an emergency lane to ensure emergency services can reach the scene of an possible accident. This lane must be formed between the left lane and the lane next to the left lane (i.e., between the two leftmost lanes).

- It is unlawful for a driver to stop his or her vehicle on the road for any reason except in an emergency or situations where stopping is unavoidable, such as being involved in a collision. This includes stopping on emergency lanes.

- It is also unlawful to turn around or back up on the Autobahn under any circumstances. Doing so is punishable under criminal law.

- The distance between vehicles (in metres) should be at least half the speed (in km/h) at all times (e.g. at least 60 metres at 120 km/h). This corresponds to a "lead time" of just under 2 seconds. Again, the fact that the car in front is illegally occupying the left-hand lane when the right-hand lane is free does not excuse following too closely.

- Fines for tailgating were increased in May 2006. At speeds of over 100 km/h, keeping less than 30 percent of the recommended distance now results in the suspension of one's driving licence for one to three months.

- The legal regulations (Straßenverkehrsordnung) explicitly allow drivers to honk or flash headlights shortly in order to indicate intention of overtaking.[9]. Obtrusive behaviour of the potentially overtaking car, such as constantly flashing headlights or driving at insufficient distances for a longer period of time is illegal and may be prosecuted as coercion. This may also apply to drivers not allowing faster cars to overtake their car if the traffic situation allows it (e.g. by occupying the left-hand lane for a longer period of time)[10].

- Tires must be approved for the vehicle's top speed. Tires for lower speeds (i.e., cheaper than high-speed tires) are only allowed if they are marked as Winter tires (M+S or M/S). In this case the driver must have a sticker in the windshield as a reminder of the maximum speed.

Rest areas on the autobahn

Along the Autobahn, the drivers can stop at rest areas for fuel, food and beverages. In Germany, they are called Raststätte(n), while in Austria they are known as Raststation(en). These rest areas have restaurants serving breakfast, lunch and dinner. The restaurants may legally serve alcoholic beverages. Many of the rest stops also have motels. In Germany, the rest areas were operated by a government-owned company until 1998, when it was privatised.

References

- ↑ "Europas erste Autobahn wird 75" (in German). Spiegel Online (2007-08-04).

- ↑ German Myth 8 Hitler and the autobahn German.about.com

- ↑ "Gesetz über die Errichtung eines Unternehmens "Reichsautobahnen"" (in German). www.verfassungen.de.

- ↑ Richard Vahrenkamp (2006-09-06). "Roads without Cars: The HAFRABA Association and the Autobahn Project 1933-1943 in Germany" (PDF).

- ↑ Traffic and Accident Data - Germany (Summary Statistics). Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen (BASt) [1] [2]

- ↑ The Berlin Wall opened in 1989, and German reunification was effective in 3 October 1990, but statistics for 1990 and prior are for the former West Germany states only.

- ↑ Article from "Abendblatt" concerning so called "Sprinter-Unfälle"(Sprinter-accidents)

- ↑ Noetigung

- ↑ § 5 (5) StVO

- ↑ Noetigung

See also

- German Autobahns

- Swiss Autobahns

- Autobahns of Austria

- Highway

- Freeway

- Motorway

- Road transport

- Toll road

- List of German expressions in English

- Autoroute (France)

- Autostrada (Italy)

- Autostrada (Poland)

- Autostrada (Romania)

Film

- Reichsautobahn (documentary/b&w) by Hartmut Bitomsky (West Germany, 1986)

External links

- http://www.autobahnen.ch/ — Website with pictures, forum and routes of Swiss motorways

- http://www.autobahnatlas-online.de/ — German website with descriptions of all autobahn routes and exits. (Internet Explorer is recommended for viewing)

- http://motorways-exitlists.com/index.htm — Website with descriptions of motorway routes worldwide.

- http://bundesrecht.juris.de/stvo/index.html — German traffic laws, including those concerning the Autobahn (German only)

- New Autobahn speed limit proposal? - AutomoBlog.net

- Official website of Tank & Rast, operator of Autobahn rest stations (Raststätte) in Germany

- Official roads website of the German Transport Ministry

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||