Atlantic hurricane

An Atlantic hurricane or tropical storm is a tropical cyclone that forms in the North Atlantic Ocean, usually in summer or autumn. Tropical storms have one-minute maximum sustained winds of at least 39 mph (34 knots, 17 m/s, 63 km/h), while hurricanes have one-minute maximum sustained exceeding 74 mph (64 knots, 33 m/s, 119 km/h).[1] When applied to tropical cyclones, "Atlantic" generally refers to the entire "Atlantic basin", which includes the North Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico.

Most Atlantic tropical storms and hurricanes form between June 1 and November 30.[2] The United States National Hurricane Center monitors the basin and issues reports, watches and warnings about tropical weather systems for the Atlantic Basin as one of the Regional Specialized Meteorological Centers for tropical cyclones as defined by the World Meteorological Organization.[3]

Tropical disturbances that reach tropical storm intensity are named from a pre-determined list. Hurricanes that result in significant damage or casualties may have their names retired from the list at the request of the affected nations in order to prevent confusion should a subsequent storm be given the same name.[4] On average, 10.1 named storms occur each season, with an average of 5.9 becoming hurricanes and 2.5 becoming major hurricanes (Category 3 or greater). The climatological peak of activity is around September 10 each season.[5]

Contents |

Steering factors

Tropical cyclones are steered by the surrounding flow throughout the depth of the troposphere (the atmosphere from the surface to about eight miles (12 km) high). Neil Frank, former director of the United States National Hurricane Center, used the analogies such as "a leaf carried along in a stream" or a "brick moving through a river of air" to describe the way atmospheric flow affects the path of a hurricane across the ocean. Specifically, air flow around high pressure systems and toward low pressure areas influence hurricane tracks.

In the tropical latitudes, tropical storms and hurricanes generally move westward with a slight tend toward the north, under the influence of the subtropical ridge, a high pressure system that usually extends east-west across the subtropics.[6] South of the subtropical ridge, surface easterly winds (blowing from east to west) prevail. If the subtropical ridge is weakened by an upper trough, a tropical cyclone may turn poleward and then recurve,[7] or curve back toward the northeast into the main belt of the Westerlies. Poleward (north) of the subtropical ridge, westerly winds prevail and generally steer tropical cyclones that reach northern latitudes toward the east. The westerlies also steer extratropical cyclones with their cold and warm fronts from west to east. [8]

Climatology

| Month | Total | Average |

|---|---|---|

| January–April | 5 | <0.1 |

| May | 19 | 0.1 |

| June | 80 | 0.5 |

| July | 102 | 0.6 |

| August | 347 | 2.2 |

| September | 466 | 3.0 |

| October | 281 | 1.8 |

| November | 61 | 0.4 |

| December | 11 | 0.1 |

| Total | 1,372 | 8.7 |

| Source: NOAA + additions for 2007 | ||

- See also: Tropical cyclogenesis

Climatology does serve to characterize the general properties of an average season and can be used as one of many other tools for making forecasts. Most storms form in warm waters several hundred miles north of the equator near the Intertropical convergence zone from tropical waves. The Coriolis force is usually too weak to initiate sufficient rotation near the equator.[9] Storms frequently form in the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Sea, and the tropical Atlantic Ocean as far east as the Cape Verde Islands, the origin of strong and long-lasting Cape Verde-type hurricanes. Systems may also strengthen over the Gulf Stream off the coast of the eastern United States, wherever water temperatures exceed 26.5 °C (79.7 °F).[9]

Although most storms are found within tropical latitudes, occasionally storms will form further north and east from disturbances other than tropical waves such as cold fronts and upper-level lows. There is a strong correlation between Atlantic hurricane activity in the tropics and the presence of an El Niño or La Niña in the Pacific Ocean. El Niño events increase the wind shear over the Atlantic, producing a less-favorable environment for formation and decreasing tropical activity in the Atlantic basin. Conversely, La Niña causes an increase in activity due to a decrease in wind shear. [10]

June

The beginning of the hurricane season is most closely related to the timing of increases in sea surface temperatures, convective instability, and other thermodynamic factors. [11] Although this month marks the beginning of the hurricane season, the month of June generally sees little activity, with an average of about 1 tropical cyclone every 2 years. Tropical systems usually form in the Gulf of Mexico or off the east coast of the United States.[12]

July

Not much tropical activity occurs during the month of July, but the majority of hurricane seasons see the formation of one tropical cyclone during July. Using data from 1944 to 1996, on average, half of the hurricane seasons had their first tropical storm by July 11, with a second having formed by August 8.[5]

Formation usually occurs in the eastern Caribbean Sea around the Lesser Antilles, in the northern and eastern parts of the Gulf of Mexico, in the vicinity of the northern Bahamas, and off the coast of The Carolinas and Virginia over the Gulf Stream. Storms travel westward through the Caribbean and then either move towards the north and curve near the eastern coast of the United States or stay on a north-westward track and enter the Gulf of Mexico.[12]

August

Decrease in wind shear from July to August produces a significant increase of tropical activity [13]. An average of 2.8 tropical storms develop annually in August. On average, four named systems and one hurricane occur by August 30, and by September 4, the Atlantic ocean has spawned its first major hurricane.[5]

September

The peak of the hurricane season occurs in September and corresponds to low wind shear [13] and the warmest sea surface temperatures[14]. The month of September sees an average of 3 storms a year. By September 24, the average season sees 7 named systems, 4 of which are hurricanes. In addition, two major hurricanes occur on average by September 28.[5]

October

The favorable conditions found during September begin to decay in October. The main reason for the decrease in activity is increasing wind shear, although sea surface temperatures are cooler than in September. [11] Activity falls off markedly, with 1.8 cyclones developing on average, though there is a climatological secondary peak around October 20.[15]. By October 21, the average season is expected to have 9 named storms with 5 hurricanes. A third major hurricane would be expected sometime between September 28 and the end of the year for half of all seasons.[5] In contrast to mid-season activity, the mean locus of formation shifts westward to the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, a reverse trend to the eastward progression of June through August.[12]

November

Wind shear from westerlies increases substantially through November, generally preventing cyclone formation. [11] On average, one storm forms during November every other year. On rare occasions, a major hurricane forms, such as Category 4 Hurricane Lenny in 1999, which formed in mid November, and Hurricane Kate, a Category 3 which formed in late November 1985.[12]

December to May

- Further information: Off-season storms

Few tropical cyclones can be found in the time between seasons, though about one-third of the years since 1944 have experienced an off-season tropical or subtropical cyclone. In the 63 seasons between 1944 and 2008, 9 tropical cyclones of tropical storm strength formed in May, 8 in December, and 4 total for all four months between January and April.[12] High vertical wind shear and low sea surface temperatures generally preclude formation. Though a tropical cyclone has been observed in the Atlantic basin in every month in the year, no tropical cyclone is officially documented to have initially formed in January. A subtropical cyclone formed in January in the 1978 season, and both Hurricane Alice and Tropical Storm Zeta formed in December and lasted into January.[12]

Extremes

- See also: List of Atlantic hurricane records

- The season in which the most tropical storms formed on record was the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season (28). That season was also the one in which the most hurricanes formed on record (15).[12]

- The 1950 Atlantic hurricane season had the most major hurricanes on record (8).[12]

- The least active season on record since 1944 (when the database is considered more reliable) was the 1983 Atlantic hurricane season, with one tropical storm, two hurricanes, and one major hurricane. Overall, the 1914 Atlantic hurricane season remains the least active, with only one documented storm.[12]

- The most intense hurricane on record to form in the North Atlantic basin was Hurricane Wilma (2005) (882 mbar).[12]

- The longest-lasting hurricane was the San Ciriaco Hurricane of 1899 (28 days).[12]

- The fastest-moving hurricane was Hurricane Emily (1987) at 69 mph.[12]

- The most tornadoes spawned by a hurricane was 127 by Hurricane Ivan (2004 season).[12]

- The strongest landfalling hurricane was the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 (892 hPa).[12]

- The deadliest hurricane was the Great Hurricane of 1780 (22,000 fatalities).[16]

- Use of radius of outermost closed isobar statistics indicate that Hurricane Ike was the largest tropical cyclone ever observed in the Atlantic basin.[17]

- The most damaging hurricane (adjusted for inflation) was Hurricane Katrina of the 2005 season which caused $81.2 billion in damages (2005 USD).[18]

Trends

- See also: Atlantic hurricane reanalysis

While the number of storms in the Atlantic has increased since 1995, there is no obvious global trend; the annual number of tropical cyclones worldwide remains about 87 ± 10. However, the ability of climatologists to make long-term data analysis in certain basins is limited by the lack of reliable historical data in some basins, primarily in the Southern Hemisphere.[19] In spite of that, there is some evidence that the intensity of hurricanes is increasing. Kerry Emanuel stated, "Records of hurricane activity worldwide show an upswing of both the maximum wind speed in and the duration of hurricanes. The energy released by the average hurricane (again considering all hurricanes worldwide) seems to have increased by around 70% in the past 30 years or so, corresponding to about a 15% increase in the maximum wind speed and a 60% increase in storm lifetime."[20] Emanuel theorized at the time that increased heat from global warming was driving this trend. However, Emanuel's own research in 2008 refuted this theory and many others contend that the trend doesn't exist at all, but is instead a figment created by faulty readings from primitive 1970s-era measurement equipment.

Atlantic storms are becoming more destructive financially, since five of the ten most expensive storms in United States history have occurred since 1990. According to the World Meteorological Organization, “recent increase in societal impact from tropical cyclones has largely been caused by rising concentrations of population and infrastructure in coastal regions.”[21] Pielke et al. (2008) normalized mainland U.S. hurricane damage from 1900–2005 to 2005 values and found no remaining trend of increasing absolute damage. The 1970s and 1980s were notable because of the extremely low amounts of damage compared to other decades. The decade 1996–2005 has the second most damage among the past 11 decades, with only the decade 1926–1935 surpassing its costs. The most damaging single storm is the 1926 Miami hurricane, with $157 billion of normalized damage.[22]

Often in part because of the threat of hurricanes, many coastal regions had sparse population between major ports until the advent of automobile tourism; therefore, the most severe portions of hurricanes striking the coast may have gone unmeasured in some instances. The combined effects of ship destruction and remote landfall severely limit the number of intense hurricanes in the official record before the era of hurricane reconnaissance aircraft and satellite meteorology. Although the record shows a distinct increase in the number and strength of intense hurricanes, therefore, experts regard the early data as suspect.[23] Christopher Landsea et al. estimated an undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910. These undercounts roughly take into account the typical size of tropical cyclones, the density of shipping tracks over the Atlantic basin, and the amount of populated coastline.[24]

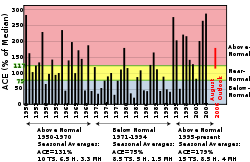

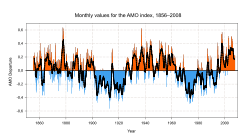

The number and strength of Atlantic hurricanes may undergo a 50–70 year cycle, also known as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. Nyberg et al. reconstructed Atlantic major hurricane activity back to the early 18th century and found five periods averaging 3–5 major hurricanes per year and lasting 40–60 years, and six other averaging 1.5–2.5 major hurricanes per year and lasting 10–20 years. These periods are associated with the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation. Throughout, a decadal oscillation related to solar irradiance was responsible for enhancing/dampening the number of major hurricanes by 1–2 per year.[25]

Although more common since 1995, few above-normal hurricane seasons occurred during 1970–94.[26] Destructive hurricanes struck frequently from 1926–60, including many major New England hurricanes. Twenty-one Atlantic tropical storms formed in 1933, a record only recently exceeded in 2005, which saw 28 storms. Tropical hurricanes occurred infrequently during the seasons of 1900–25; however, many intense storms formed during 1870–99. During the 1887 season, 19 tropical storms formed, of which a record 4 occurred after November 1 and 11 strengthened into hurricanes. Few hurricanes occurred in the 1840s to 1860s; however, many struck in the early 19th century, including an 1821 storm that made a direct hit on New York City. Some historical weather experts say these storms may have been as high as Category 4 in strength.[27]

These active hurricane seasons predated satellite coverage of the Atlantic basin. Before the satellite era began in 1960, tropical storms or hurricanes went undetected unless a reconnaissance aircraft encountered one, a ship reported a voyage through the storm, or a storm hit land in a populated area.[23] The official record, therefore, could miss storms in which no ship experienced gale-force winds, recognized it as a tropical storm (as opposed to a high-latitude extra-tropical cyclone, a tropical wave, or a brief squall), returned to port, and reported the experience.

Proxy records based on paleotempestological research have revealed that major hurricane activity along the Gulf of Mexico coast varies on timescales of centuries to millennia.[28][29] Few major hurricanes struck the Gulf coast during 3000–1400 BC and again during the most recent millennium. These quiescent intervals were separated by a hyperactive period during 1400 BC and 1000 AD, when the Gulf coast was struck frequently by catastrophic hurricanes and their landfall probabilities increased by 3–5 times. This millennial-scale variability has been attributed to long-term shifts in the position of the Azores High,[29] which may also be linked to changes in the strength of the North Atlantic Oscillation.[30]

According to the Azores High hypothesis, an anti-phase pattern is expected to exist between the Gulf of Mexico coast and the Atlantic coast. During the quiescent periods, a more northeasterly position of the Azores High would result in more hurricanes being steered towards the Atlantic coast. During the hyperactive period, more hurricanes were steered towards the Gulf coast as the Azores High was shifted to a more southwesterly position near the Caribbean. Such a displacement of the Azores High is consistent with paleoclimatic evidence that shows an abrupt onset of a drier climate in Haiti around 3200 14C years BP,[31] and a change towards more humid conditions in the Great Plains during the late-Holocene as more moisture was pumped up the Mississippi Valley through the Gulf coast. Preliminary data from the northern Atlantic coast seem to support the Azores High hypothesis. A 3000-year proxy record from a coastal lake in Cape Cod suggests that hurricane activity increased significantly during the past 500–1000 years, just as the Gulf coast was amid a quiescent period of the last millennium.

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Atlantic hurricane seasons

- South Atlantic tropical cyclone

- List of named tropical cyclones

- Mediterranean tropical cyclone

- Pacific hurricane

References

- ↑ National Hurricane Center. Glossary of NHC/TPC Terms. Retrieved on 2006-10-28.

- ↑ Chris Landsea. Subject: E16) When did the earliest and latest hurricanes occur? Retrieved on 2008-06-10.

- ↑ World Meteorological Organization (April 25, 2006). "RSMCs". Tropical Cyclone Programme (TCP). Retrieved on 2006-11-05.

- ↑ NOAA The Retirement of Hurricane Names. Retrieved on 2008-06-10.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 National Hurricane Center. Tropical Cyclone Climatology. Retrieved on 2008-06-10.

- ↑ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What determines the movement of tropical cyclones?". NOAA. Retrieved on 2006-07-25.

- ↑ U. S. Navy. Section 2: Tropical Cyclone Motion Terminology. Retrieved on 2007-04-10.

- ↑ Hurricane Research Division. Frequently Asked Questions: Subject G6) What determines the movement of tropical cyclones? Retrieved on 2006-10-28.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: How do tropical cyclones form?". NOAA. Retrieved on 2006-07-26.

- ↑ Marc C. Cove, James J. O'Brien, et al. Effect of El Niño on U.S. Landfalling Hurricanes, Revisited. Retrieved on 2006-10-28.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 William M. Gray and Philip J. Klotzbach. SUMMARY OF 2005 ATLANTIC TROPICAL CYCLONE ACTIVITY AND VERIFICATION OF AUTHOR’S SEASONAL AND MONTHLY FORECASTS. Retrieved on 2006-10-28.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 National Hurricane Center.Atlantic Hurricane Database. Retrieved on 2008-06-10.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Anantha R. Aiyyer. Climatology of Vertical Wind Shear Over the Tropical Atlantic. Retrieved on 2006-10-28.

- ↑ Chris Landsea. Frequently Asked Questions: G5) Why do tropical cyclones occur primarily in the summer and autumn? Retrieved on 2006-10-28.

- ↑ NOAA. Graph showing average activity during the hurricane Season. Retrieved on 2006-10-28.

- ↑ Edward N. Rappaport and Jose Fernandez-Partagas. The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492-1996. Retrieved on 2008-06-10.

- ↑ Masters, Jeff (2008-09-12). "Ike's record size.". Weather Underground. Retrieved on 2008-09-27.

- ↑ Eric S. Blake, Edward N. Rappaport, and Chris Landsea. The Dealiest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones From 1851 to 2006 (and other frequently requested hurricane facts). Retrieved on 2008-03-19.

- ↑ Landsea, Chris, et al. (July 28, 2006). "Can We Detect Trends in Extreme Tropical Cyclones?" (PDF). Science 313: 452–454. doi:. PMID 16873634. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/Landsea/landseaetal-science06.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-06-09.

- ↑ Emanuel, Kerry (January 2006). "Anthropogenic Effects on Tropical Cyclone Activity". Retrieved on 2006-03-30.

- ↑ World Meteorological Organization (2006-12-04). "Summary Statement on Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change" (PDF). Press release.

- ↑ Pielke, Roger A., Jr.; et al. (2008). "Normalized Hurricane Damage in the United States: 1900–2005". Natural Hazards Review 9 (1): 29–42. doi:. http://forecast.mssl.ucl.ac.uk/shadow/docs/Pielkeetal2006a.pdf.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Neumann, Charles J.. "1.3: A Global Climatology". Global Guide to Tropical Cyclone Forecasting. Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved on 2006-11-30.

- ↑ Landsea, C. W.; et al. (2004). "The Atlantic hurricane database re-analysis project: Documentation for the 1851–1910 alterations and additions to the HURDAT database". in Murname, R. J.; Liu, K.-B.. Hurricanes and Typhoons: Past, Present and Future. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 177–221. ISBN 0231123884.

- ↑ Nyberg, J.; Winter, A.; Malmgren, B. A. (2005). "Reconstruction of Major Hurricane Activity". Eos Trans. AGU 86 (52, Fall Meet. Suppl.): Abstract PP21C-1597. http://www.agu.org/cgi-bin/wais?dd=PP21C-1597.

- ↑ Risk Management Solutions (March 2006). "U.S. and Caribbean Hurricane Activity Rates." (PDF). Retrieved on 2006-11-30.

- ↑ Center for Climate Systems Research. "Hurricanes, Sea Level Rise, and New York City". Columbia University. Retrieved on 2006-11-29.

- ↑ Liu, Kam-biu (1999). "Millennial-scale variability in catastrophic hurricane landfalls along the Gulf of Mexico coast" in 23d Conf. on Hurricanes and Tropical Meteorology.: 374–377, Dallas, TX: Amer. Meteor. Soc..

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Liu, Kam-biu; Fearn, Miriam L. (2000). "Reconstruction of Prehistoric Landfall Frequencies of Catastrophic Hurricanes in Northwestern Florida from Lake Sediment Records". Quaternary Research 54 (2): 238–245. doi:.

- ↑ Elsner, James B.; Liu, Kam-biu; Kocher, Bethany (2000). "Spatial Variations in Major U.S. Hurricane Activity: Statistics and a Physical Mechanism". Journal of Climate 13 (13): 2293–2305. doi:.

- ↑ Higuera-Gundy, Antonia; et al. (1999). "A 10,300 14C yr Record of Climate and Vegetation Change from Haiti". Quaternary Research 52 (2): 159–170. doi:.