Athabasca Oil Sands

The Athabasca Oil Sands (also known as the Athabasca Tar Sands) are large deposits of bitumen, or extremely heavy crude oil, located in northeastern Alberta, Canada. These oil sands consist of a mixture of crude bitumen (a semi-solid form of crude oil), silica sand, clay minerals, and water. The Athabasca deposit is the largest reservoir of crude bitumen in the world and the largest of three major oil sands deposits in Alberta, along with the nearby Peace River and Cold Lake deposits. Together, these oil sand deposits lie under 141,000 square kilometres (54,000 sq mi) of sparsely populated boreal forest and muskeg (peat bogs) and contain about 1.7 trillion barrels (270×109 m3) of bitumen in-place, comparable in magnitude to the world's total proven reserves of conventional petroleum.

With modern non-conventional oil production technology, at least 10% of these deposits, or about 170 billion barrels (27×109 m3) were considered to be economically recoverable at 2006 prices, making Canada's total oil reserves the second largest in the world, after Saudi Arabia's. The Athabasca deposit is the only large oil sands reservoir in the world which is suitable for large-scale surface mining, although most of it can only be produced using more recently developed in-situ technology.[1]

Environmental impacts

- See also: Tar sands#Environment

Critics contend that government and industry measures taken to minimize environmental and health risks posed by large-scale mining operations are inadequate, causing damage to the natural environment.[2][3] Objective discussion of the environmental impacts has often been clouded by polarized arguments from industry and from advocacy groups.[4][5][6]

Land

Alberta's oil sands are developed through open-pit mining for approximately 20 percent of the deposit, and in situ extraction technologies for the remainder 80 per cent of the deposit. Open pit mining destroys the Boreal forest of Canada and muskeg. The Alberta government requires companies to restore the land to "equivalent land capability". This means that the ability of the land to support various land uses after reclamation is similar to what existed, but that the individual land uses may not necessarily be identical.[7] In some particular circumstances the government considers agricultural land to be equivalent to forest land, oil sands companies have reclaimed mined land to use as pasture for endangered buffalo instead of restoring it to the original boreal forest and muskeg.

Birds

In April 2008, 500 birds died when they landed in a toxic tailing pond at Syncrude's facility. Recent studies show that up to 150 millions migrating birds will die because of oil sands developments in the next 20 years.

Water

A Pembina Institute report stated "To produce one cubic metre (m³) of synthetic crude oil (SCO) (upgraded bitumen) in a mining operation requires about 2–4.5 m³ of water (net figures). Approved oil sands mining operations are currently licensed to divert 359 million m³ from the Athabasca River, or more than twice the volume of water required to meet the annual municipal needs of the City of Calgary."[8] and went on to say "...the net water requirement to produce a cubic metre of oil with in situ (emphasis added) production may be as little as 0.2 m³, depending on how much is recycled". Jeffrey Simpson of the Globe and Mail paraphrased this report, saying: "A cubic metre of oil, mined from the tar sands, needs two to 4.5 cubic metres of water. Approved oil sands mining operations -- not the in situ kind that extract oil from tar sands far below the surface -- will take twice the annual water needs of the City of Calgary. The water will come from the Athabasca River, from which 359-million cubic metres will be diverted."[3]

The Athabasca River runs 1,231 kilometres from the Athabasca Glacier in west-central Alberta to Lake Athabasca in northeastern Alberta [9]. The average annual flow just downstream of Fort McMurray is 633 cubic metres per second [10] with its highest daily average measuring 1,200 cubic metres per second [11].

Current water license allocations totals about 1.8% of the Athabasca river flow. Actual use in 2006 was about 0.4%[12]. In addition, the Alberta government sets strict limits on how much water oil sands companies can remove from the Athabasca River. According to the Water Management Framework for the Lower Athabasca River, during periods of low river flow water consumption from the Athabasca River is limited to 1.3% of annual average flow. [13] The province of Alberta is also looking into cooperative withdrawal agreements between oil sands operators.[14]

Greenhouse gases

The processing of bitumen into synthetic crude requires energy, and currently this energy is generated by burning natural gas, which releases carbon dioxide. For every barrel of synthetic oil produced in Alberta, more than 80 kg of greenhouse gases are released[15] into the atmosphere and between 2,000 and 4,000 barrels (640 m3) of waste water are dumped into tailing ponds that have replaced about 50 km² of forest. The forecast growth in synthetic oil production in Alberta also threatens Canada's international commitments. In ratifying the Kyoto Protocol, Canada agreed to reduce, by 2012, its greenhouse gas emissions by 6% with respect to 1990. In 2002, Canada's total greenhouse gas emissions had increased by 24% since 1990. Oil Sands production contributed 3.4% of Canada's greenhouse gas emissions in 2003 [16].

Ranked as the world's eighth largest emitter of greenhouse gases,[17] Canada is a relatively large emitter given its population and is missing its Kyoto targets. A major Canadian initiative called the Integrated CO2 Network (ICO2N) has proposed a system for the large scale capture, transport and storage of carbon dioxide (CO2). ICO2N members represent a group of industry participants providing a framework for carbon capture and storage development in Canada, initially using it to enhance oil recovery.[18] Nuclear power has also been proposed as a means of generating the required energy without releasing green house gases.

Royal Dutch Shell - misleading advertisement

In August 2008 the British Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) ruled that Royal Dutch Shell had misled the public in an advertisement which claimed that its $10bn oil sands project in Alberta was a "sustainable energy source". The ASA upheld a complaint by WWF about Shell's advert in the Financial Times. Explaining the ruling the ASA stated that "We considered that the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) best practice guidance on environmental claims stated that green claims should not 'be vague or ambiguous, for instance by simply trying to give a good impression about general concern for the environment. Claims should always avoid the vague use of terms such as 'sustainable', 'green', 'non-polluting' and so on." Furthermore the ASA ruling stated "Defra had made that recommendation because, although 'sustainable' was a widely used term, the lack of a universally agreed definition meant that it was likely to be ambiguous and unclear to consumers. Because we had not seen data that showed how Shell was effectively managing carbon emissions from its oil sands projects in order to limit climate change, we concluded that the ad was misleading"[19]

History

The Athabasca oil sands are named after the Athabasca River which cuts through the heart of the deposit, and traces of the heavy oil are readily observed on the river banks. Historically, the bitumen was used by the indigenous Cree and Dene Aboriginal peoples to waterproof their canoes.[20] The oil deposits are located within the boundaries of Treaty 8, and several First Nations of the area are involved with the sands.

The Athabasca oil sands first came to the attention of European fur traders in 1719 when Wa-pa-su, a Cree trader, brought a sample of bituminous sands to the Hudson's Bay Company post at York Factory on Hudson Bay where Henry Kelsey was the manager. In 1778, Peter Pond, another fur trader and a founder of the rival North West Company, became the first European to see the Athabasca deposits after discovering the Methye Portage which allowed access to the rich fur resources of the Athabasca River system from the Hudson Bay watershed.[21]

In 1788, fur trader Alexander MacKenzie (who later discovered routes to both the Arctic and Pacific Oceans from this area) wrote: "At about 24 miles (39 km) from the fork (of the Athabasca and Clearwater Rivers) are some bituminous fountains into which a pole of 20 feet (6.1 m) long may be inserted without the least resistance. The bitumen is in a fluid state and when mixed with gum, the resinous substance collected from the spruce fir, it serves to gum the Indians' canoes." He was followed in 1799 by map maker David Thompson and in 1819 by British Naval officer Sir John Franklin.[22]

Sir John Richardson did the first geological assessment of the oil sands in 1848 on his way north to search for Franklin's lost expedition. The first government-sponsored survey of the oil sands was initiated in 1875 by John Macoun, and in 1883, G.C. Hoffman of the Geological Survey of Canada tried separating the bitumen from oil sand with the use of water and reported that it separated readily. In 1888, Dr. Robert Bell, the director of the Geological Survey of Canada, reported to a Senate Committee that "The evidence ... points to the existence in the Athabasca and Mackenzie valleys of the most extensive petroleum field in America, if not the world." [21]

In 1926, Dr. Karl Clark of the University of Alberta perfected a steam separation process which became the basis of today's thermal extraction process. Several attempts to implement it had varying degrees of success, but it was 1967 before the first commercially viable operation began with the opening of the Great Canadian Oil Sands (now Suncor) plant using surfactants in the separation process developed by Dr. Earl W. Malmberg of Sun Oil Company.

Development

The key characteristic of the Athabasca deposit is that it is the only one shallow enough to be suitable for surface mining. About 10% of the Athabasca oil sands are covered by less than 75 metres (246 ft) of overburden. The mineable area as defined by the Alberta government covers 37 contiguous townships (about 3,400 km2/1,300 sq mi) north of the city of Fort McMurray. The overburden consists of 1 to 3 metres of water-logged muskeg on top of 0 to 75 metres of clay and barren sand, while the underlying oil sands are typically 40 to 60 metres thick and sit on top of relatively flat limestone rock. As a result of the easy accessibility, the world's first oil sands mine was started by Great Canadian Oil Sands Limited (a predecessor company of Suncor Energy) in 1967. The Syncrude mine (the biggest mine in the world) followed in 1978, and the Albian Sands mine (operated by Shell Canada) in 2003. All three of these mines are associated with bitumen upgraders that convert the unusable bitumen into synthetic crude oil for shipment to refineries in Canada and the United States. At Albian, the upgrader is located at Scotford, 439 km south. The bitumen, diluted with a solvent is transferred there in a 610 millimetres (24 in) Corridor Pipeline.

Population

The Athabasca oil sands are located in the northeastern corner of the Canadian province of Alberta, near the city of Fort McMurray. The area is only sparsely populated, and in the late 1950s, it was primarily a wilderness outpost of a few hundred people whose main economic activities included fur trapping and salt mining. From a population of 37,222 in 1996, the boomtown of Fort McMurray and the surrounding region (known as the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo) grew to 79,810 people as of 2006, including a "shadow population" of 10,442 living in work camps,[23] leaving the community struggling to provide services and housing for migrant workers, many of them from Eastern Canada, especially Newfoundland. Fort McMurray ceased to be an incorporated city in 1995 and is now an urban service area within Wood Buffalo.[24]

Estimated oil reserves

The Alberta government's Energy and Utilities Board (EUB) estimated in 2007 that about 173 billion barrels (27.5×109 m3) of crude bitumen are economically recoverable from the three Alberta oil sands areas based on benchmark WTI market prices of $62 per barrel in 2006, rising to a projected $69 per barrel in 2016 using current technology. This was equivalent to about 10% of the estimated 1,700 billion barrels (270×109 m3) of bitumen-in-place.[25] In fact WTI prices topped $133 in May 2008. Alberta estimated that the Athabasca deposits alone contain 35 billion barrels (5.6×109 m3) of surface mineable bitumen and 98 billion barrels (15.6×109 m3) of bitumen recoverable by in-situ methods. These estimates of Canada's reserves were doubted when they were first published but are now largely accepted by the international oil industry. This volume placed Canadian proven reserves second in the world behind those of Saudi Arabia.

The method of calculating economically recoverable reserves that produced these estimates was adopted because conventional methods of accounting for reserves gave increasingly meaningless numbers. They made it appear that Alberta was running out of oil at a time when rapid increases in oil sands production were more than offsetting declines in conventional oil, and in fact most of Alberta's oil production is now non-conventional oil. Conventional estimates of oil reserves are really calculations of the geological risk of drilling for oil, but in the oil sands there is very little geological risk because they outcrop on the surface and are easy to locate. With the oil price increases since 2003, the economic risk of low oil prices was reduced.

The Alberta estimates only assume a recovery rate of around 20% of bitumen-in-place, whereas oil companies using the steam assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) method of extracting bitumen report that they can recover over 60% with little effort.

Only 3% of the initial established crude bitumen reserves have been produced since commercial production started in 1967. At rate of production projected for 2015, about 3 million barrels per day (480×103 m3/d), the Athabasca oil sands reserves would last over 170 years.[26] However those production levels require an influx of workers into an area that until recently was largely uninhabited. By 2007 this need in northern Alberta drove unemployment rates in Alberta and adjacent British Columbia to the lowest levels in history. As far away as the Atlantic Provinces, where workers were leaving to work in Alberta, unemployment rates fell to levels not seen for over one hundred years.[27]

The Venezuelan Orinoco tar sands site may contain more oil sands than Athabasca. However, while the Orinoco deposits are less viscous and more easily produced using conventional techniques (the Venezuelan government prefers to call them "extra-heavy oil"), they are too deep to access by surface mining.

Economics

Despite the large reserves, the cost of extracting the oil from bituminous sands has historically made production of the oil sands unprofitable—the cost of selling the extracted crude would not cover the direct costs of recovery; labour to mine the sands and fuel to extract the crude.

In mid-2006, the National Energy Board of Canada estimated the operating cost of a new mining operation in the Athabasca oil sands to be C$9 to C$12 per barrel, while the cost of an in-situ SAGD operation (using dual horizontal wells) would be C$10 to C$14 per barrel.[28] This compares to operating costs for conventional oil wells which can range from less than one dollar per barrel in Iraq and Saudi Arabia to over six in the United States and Canada's conventional oil reserves.

The capital cost of the equipment required to mine the sands and haul it to processing is a major consideration in starting production. The NEB estimates that capital costs raise the total cost of production to C$18 to C$20 per barrel for a new mining operation and C$18 to C$22 per barrel for a SAGD operation. This does not include the cost of upgrading the crude bitumen to synthetic crude oil, which makes the final costs C$36 to C$40 per barrel for a new mining operation.

Therefore, although high crude prices make the cost of production very attractive, sudden drops in price leaves producers unable to recover their capital costs—although the companies are well financed and can tolerate long periods of low prices since the capital has already been spent and they can typically cover incremental operating costs.

However, the development of commercial production is made easier by the fact that exploration costs are very low. Such costs are a major factor when assessing the economics of drilling in a traditional oil field. The location of the oil deposits in the oil sands are well known, and an estimate of recovery costs can usually be made easily. There is not another region in the world with energy deposits of comparable magnitude where it would be less likely that the installations would be confiscated by a hostile national government, or be endangered by a war or revolution.

As a result of the oil price increases since 2003, the economics of oil sands have improved dramatically. At a world price of US$50 per barrel, the NEB estimated an integrated mining operation would make a rate return of 16 to 23%, while a SAGD operation would return 16 to 27%. Prices since 2006 have risen, exceeding US$145 in mid 2008. As a result, capital expenditures in the oil sands announced for the period 2006 to 2015 are expected to exceed C$100 billion, which is twice the amount projected as recently as 2004. However, because of an acute labour shortage which has developed in Alberta, it is not likely that all these projects can be completed.

At present the area around Fort McMurray has seen the most effect from the increased activity in the oil sands. Although jobs are plentiful, housing is in short supply and expensive. People seeking work often arrive in the area without arranging accommodation, driving up the price of temporary accommodation. The area is isolated, with only a two-lane road connecting it to the rest of the province, and there is pressure on the government of Alberta to improve road links as well as hospitals and other infrastructure.[28]

Despite the best efforts of companies to move as much of the construction work as possible out of the Fort McMurray area, and even out of Alberta, the shortage of skilled workers is spreading to the rest of the province.[29]. Even without the oil sands, the Alberta economy would be very strong, but development of the oil sands has resulted in the strongest period of economic growth ever recorded by a Canadian province.[30]

Oil sands production

Commercial production of oil from the Athabasca oil sands began in 1967, when Great Canadian Oil Sands Limited (then a subsidiary of Sun Oil Company but now an independent company known as Suncor Energy) opened its first mine, producing 30,000 barrels per day (4,800 m³/d) of synthetic crude oil. Development was inhibited by declining world oil prices, and the second mine, operated by the Syncrude consortium, did not begin operating until 1978, after the 1973 oil crisis sparked investor interest. However, the price of oil subsided afterwards, and although the 1979 energy crisis caused oil prices to peak again, introduction of the National Energy Program by Pierre Trudeau discouraged foreign investment in the Canadian oil industry. During the 1980s, oil prices declined to very low levels, causing considerable retrenchment in the oil industry, and the third mine, operated by Shell Canada, did not begin operating until 2003. However, as a result of oil price increases since 2003, the existing mines have been greatly expanded and new ones are being planned.

According to the Alberta Energy and Utilities Board, 2005 production of crude bitumen in the Athabasca oil sands was as follows:

| 2005 Production | m3/day | bbl/day |

|---|---|---|

| Suncor Mine | 31,000 | 195,000 |

| Syncrude Mine | 41,700 | 262,000 |

| Shell Canada Mine | 26,800 | 169,000 |

| In Situ Projects | 21,300 | 134,000 |

| TOTAL | 120,800 | 760,000 |

As of 2006, output of oil sands production had increased to 1.126 million barrels per day (179,000 m³/d) (bbl/d). Oil sands were the source of 62% of Alberta's total oil production and 47% of all oil produced in Canada. The Alberta government believes this level of production could reach 3 Mbbl/d (480,000 m³/d) by 2020 and possibly 5 Mbbl/d (790,000 m³/d) by 2030.[31]

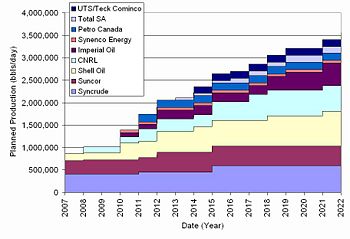

Future production

With planned projects coming on stream, by 2010 oil sands production is projected to reach 2 million barrels per day (320,000 m³/d) or about two thirds of Canadian production. By 2015 Canadian oil production may reach 4 million barrels per day (640,000 m³/d), of which only 15% will be conventional crude oil. The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers predicts that by 2020 Canadian oil production will reach 4.8 million barrels per day (760,000 m³/d), of which only about 10% will be conventional light or medium crude oil, and most of the rest will be crude bitumen and synthetic crude oil from the Athabasca oil sands.

In early December 2007, London based BP and Calgary based Husky Energy announced a 50/50 joint venture to produce and refine bitumen from the Athabasca oil sands. BP would contribute its Toledo, Ohio refinery to the joint venture, while Husky would contribute its Sunrise oil sands project. Sunrise is planned to start producing 60,000 barrels per day (9,500 m³/d) of bitumen in 2012 and may reach 200,000 bpd (30,000 m3/d) by 2015-2020. BP would modify its Toledo refinery to process 170,000 bpd (27,000 m3/d) of bitumen directly to refined products. The joint venture would solve problems for both companies, since Husky is short of refining capacity, and BP has no presence in the oil sands. It is a change of strategy for BP, since the company historically has downplayed the importance of oil sands.[32]

In mid December 2007, ConocoPhillips announced its intention to increase its oil sands production from 60,000 barrels per day (9,500 m³/d) to 1 million barrels per day (160,000 m³/d) over the next 20 years, which would make it the largest private sector oil sands producer in the world. ConocoPhillips currently holds the largest position in the Canadian oil sands with over 1 million acres (4000 km2) under lease. Other major oil sands producers planning to increase their production include Royal Dutch Shell (to 770,000 bbl/d (122,000 m³/d); Syncrude Canada (to 550,000 bbl/d (87,000 m³/d); Suncor Energy (to 500,000 bbl/d (79,000 m³/d) and Canadian Natural Resources (to 500,000 bbl/d (79,000 m³/d).[33] If all these plans come to fruition, these five companies will be producing over 3.3 million bbl/d (500,000 m³/d) of oil from oil sands by 2028.

| Major Partners | National Affiliation |

2007 Production (barrels/day) |

Planned Production (barrels/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suncor Energy | 239,100 | 500,000 | |

| Syncrude | 307,000 | 550,000 | |

| Shell, Chevron, Marathon | NL, US | 136,000 | 770,000 |

| Petro-Canada | 22,000 | 190,000 | |

| EnCana Energy | 6,000 | 500,000 | |

| ConocoPhillips | US | — | 200,000 |

| Japan Canada Oil Sands (JACOS) | Japan | 8,000 | 30,000 |

| Nexen, OPTI Canada | — | 240,000 | |

| Canadian Natural Resources Limited | — | 700,000 | |

| Devon Energy | US | — | 70,000 |

| Synenco Energy, Sinopec | China | — | 100,000 |

| Imperial Oil, ExxonMobil | US | — | 300,000 |

| Husky Energy | — | 200,000 | |

| Total S.A., Enerplus | France | — | 225,000 |

| Chevron | US | — | 100,000 |

| Value Creation Inc | — | 300,000 | |

| StatoilHydro | Norway | — | 220,000 |

| Korea National Oil Corporation | Korea | — | 30,000 |

| Total | 718,100 | 5,225,000 |

Bitumen extraction

The original process for extraction of bitumen from the sands was developed by Dr. Karl Clark, working with Alberta Research Council in the 1920s.[35] Today, all of the producers doing surface mining, such as Syncrude Canada, Suncor Energy and Albian Sands Energy etc., use a variation of the Clark Hot Water Extraction (CHWE) process. In this process, the ores are mined using open-pit mining technology. The mined ore is then crushed for size reduction. Hot water at 50 — 80 °C is added to the ore and the formed slurry is transported using hydrotransport line to a primary separation vessel (PSV) where bitumen is recovered by flotation as bitumen froth. The recovered bitumen froth consists of 60% bitumen, 30% water and 10% solids by weight.[36] The recovered bitumen froth needs to be cleaned to reject the contained solids and water to meet the requirement of downstream upgrading processes.

More recently, in-situ methods like steam assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) and cyclic steam stimulation (CSS) have been developed to extract bitumen from deep deposits by injecting steam to heat the sands and reduce the bitumen viscosity so that it can be pumped out like conventional crude oil.

The standard extraction process requires huge amounts of natural gas. Currently, the oil sands industry uses about 4% of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin natural gas production. By 2015, this may increase 2.5 fold.[37]

According to the National Energy Board, it requires about 1,200 cubic feet (34 m3) of natural gas to produce one barrel of bitumen from in situ projects and about 700 cubic feet (20 m3) for integrated projects.[38] Since a barrel of oil equivalent is about 6,000 cubic feet (170 m3) of gas, this represents a large gain in energy. That being the case, it is likely that Alberta regulators will reduce exports of natural gas to the United States in order to provide fuel to the oil sands plants. As gas reserves are exhausted, however, oil upgraders will likely turn to bitumen gasification to generate their own fuel. In much the same way the bitumen can be converted into synthetic crude oil, it can also be converted into synthetic natural gas.

In-situ extraction on a commercial scale is just beginning. A project nearing completion, the Long Lake Project,[39] is designed to provide its own fuel, by on-site hydrocracking of the bitumen extracted.[40] Long Lake Phase 1 is extracting 13,000 barrels/day of bitumen as of July 2008, ramping towards a target of 72,000 in late 2009. and "upgrading" of bitumen to liquid oil in 2007, producing 60,000 bbl/day of usable oil. The hydrocracker is scheduled to complete commissioning by September 2008.[41]

Geopolitical importance

The Athabasca Oil Sands are now featured prominently in international trade talks, with energy rivals China and the United States negotiating with Canada for a bigger share of the oil sands' rapidly increasing output. Output at the oil sands is expected to quadruple between 2005 and 2015, reaching 4 million bbl/day, increasing their political and economic importance. Currently most of the oil sands production is exported to the United States.

An agreement has been signed between PetroChina and Enbridge to build a 400,000 barrels per day (64,000 m³/d) pipeline from Edmonton, Alberta, to the west coast port of Kitimat, British Columbia, to export synthetic crude oil from the oil sands to China and elsewhere in the Pacific[42], plus a 150-million-barrel-per-day (24,000,000 m³/d) pipeline running the other way to import condensate to dilute the bitumen so it will flow. Sinopec, China's largest refining and chemical company, and China National Petroleum Corporation have bought or are planning to buy shares in major oil sands development.

Indigenous peoples of the area

Indigenous peoples of the area include the Fort McKay First Nation. The oil sands themselves are located within the boundaries of Treaty 8, signed in 1899. The Fort McKay First Nation has formed several companies to service the oil sands industry and will be developing a mine on their territory.[43] Opposition remaining within the First Nation focuses on environmental stewardship issues.

Oil sand companies

There are currently three large oil sands mining operations in the area run by Syncrude Canada Limited, Suncor Energy and Albian Sands owned by Shell Canada, Chevron, and Western Oil Sands Ltd.

Major producing or planned developments in the Athabasca Oil Sands include the following projects:[44]

- Suncor Energy's Steepbank and millennium mines currently produce 263,000 barrels per day (41,800 m³/d) and its Firebag in-situ project produces 35,000 bbl/d (5,600 m³/d). It intends to spend 3.2 billion to expand its mining operations to 400,000 bbl/d (64,000 m³/d) and its in-situ production to 140,000 bbl/d (22,000 m³/d) by 2008.

- Syncrude's Mildred Lake and Aurora mines currently can produce 360,000 bbl/d (57,000 m³/d).

- Shell Canada currently operates its Muskeg River Mine producing 155,000 bbl/d (24,600 m³/d) and the Scotford Upgrader at Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta. Shell intends to open its new Jackpine mine and expand total production to 500,000 bbl/d (79,000 m³/d) over the next few years.

- Nexen's in-situ Long Lake SAGD project is on schedule to produce 70,000 bbl/d (11,000 m³/d) by late 2007, with plans to expand it to 240,000 bbl/d (38,000 m³/d) over the next 10 years.

- CNRL's $8 billion Horizon mine is planned to produce 110,000 bbl/d (17,000 m³/d) on startup in mid 2009 and grow to 300,000 bbl/d (48,000 m³/d) by 2010.

- Total S.A.'s subsidiary Deer Creek Energy is operating a SAGD project on its Joslyn lease, producing 10,000 bbl/d (1,600 m³/d). It intends on constructing its mine by 2010 to expand its production by 100,000 bbl/d (16,000 m³/d).

- Imperial Oil's 5 to 8 billion Kearl Oil Sands Project is projected to start construction in 2008 and produce 100,000 bbl/d (16,000 m³/d) by 2010. Imperial also operates a 160,000 bbl/d (25,000 m³/d) in-situ operation in the Cold Lake oil sands region.

- Synenco Energy and SinoCanada Petroleum Corp., a subsidiary of Sinopec, China's largest oil refiner, had agreed to create the 3.5 billion Northern Lights mine, projected to produce 100,000 bbl/d (16,000 m³/d) by 2009. This project has since been indefinitely deferred (as of 2007).[45]

- North American Oil Sands Corporation (NAOSC), a subsidiary of StatoilHydro, is expected to produce in the Kai Kos Dehseh project around 100,000 bbl/d (16,000 m³/d) by 2015. It is expected to ramp up production to around 100,000 barrels per day (16,000 m³/d) by around 2015.[46]

| Operator | Project | Phase | Capacity | Start-up | Regulatory Status |

| Shell Oil | Jackpine | 1A | 100,000 bbl/d (16,000 m³/d) | 2010 | Under construction |

| 1B | 100,000 bbl/d (16,000 m³/d) | 2012 | Approved | ||

| 2 | 100,000 bbl/d (16,000 m³/d) | 2014 | Applied for | ||

| Muskeg River | Existing | 155,000 bbl/d (24,600 m³/d) | 2002 | Operating | |

| Expansion | 115,000 bbl/d (18,300 m³/d) | 2010 | Approved | ||

| Pierre River | 1 | 100,000 bbl/d (16,000 m³/d) | 2018 | Applied for | |

| 2 | 100,000 bbl/d (16,000 m³/d) | 2021 | Applied for | ||

| Canadian Natural Resources | Horizon | 1 | 135,000 bbl/d (21,500 m³/d) | 2008 | Under construction |

| 2 and 3 | 135,000 bbl/d (21,500 m³/d) | 2011 | Approved | ||

| 4 | 145,000 bbl/d (23,100 m³/d) | 2015 | Announced | ||

| 5 | 162,000 bbl/d (25,800 m³/d) | 2017 | Announced | ||

| Imperial Oil | Kearl | 1 | 100,000 bbl/d (16,000 m³/d) | 2010 | Approved |

| 2 | 100,000 bbl/d (16,000 m³/d) | 2012 | Approved | ||

| 3 | 100,000 bbl/d (16,000 m³/d) | 2018 | Approved | ||

| Petro Canada | Fort Hills | 1 | 165,000 bbl/d (26,200 m³/d) | 2011 | Approved |

| debottleneck | 25,000 bbl/d (4,000 m³/d) | TBD | Approved | ||

| Suncor Energy | Millenium | 294,000 bbl/d (46,700 m³/d) | 1967 | Operating | |

| debottleneck | 23,000 bbl/d (3,700 m³/d) | 2008 | Under construction | ||

| Steepbank | debottleneck | 4,000 bbl/d (640 m³/d) | 2007 | Under construction | |

| extension | 2010 | Approved | |||

| Voyageur South | 1 | 120,000 bbl/d (19,000 m³/d) | 2012 | Applied for | |

| Syncrude | Mildred Lake & Aurora | 1 and 2 | 290,700 bbl/d (46,220 m³/d) | 1978 | Operating |

| 3 Expansion | 116,300 bbl/d (18,490 m³/d) | 2006 | Operating | ||

| 3 Debottleneck | 46,500 bbl/d (7,390 m³/d) | 2011 | Announced | ||

| 4 Expansion | 139,500 bbl/d (22,180 m³/d) | 2015 | Announced | ||

| Synenco Energy | Northern Lights | 1 | 57,250 bbl/d (9,102 m³/d) | 2010 | Applied for |

| Total S.A. | Joslyn | 1 | 50,000 bbl/d (7,900 m³/d) | 2013 | Applied for |

| 2 | 50,000 bbl/d (7,900 m³/d) | 2016 | Applied for | ||

| 3 | 50,000 bbl/d (7,900 m³/d) | 2019 | Announced | ||

| 4 | 50,000 bbl/d (7,900 m³/d) | 2022 | Announced | ||

| UTS/Teck Cominco | Equinox | Lease 14 | 50,000 bbl/d (7,900 m³/d) | 2014 | Public disclosure |

| Frontier | 1 | 100,000 bbl/d (16,000 m³/d) | 2014 | Public disclosure |

See also

- Canadian Centre for Energy Information

- History of the petroleum industry in Canada (oil sands and heavy oil)

- Mackenzie Valley Pipeline

References

- ↑ "Alberta's Oil Sands 2006" (PDF). Government of Alberta (2007). Retrieved on 2008-02-17.

- ↑ "Alberta Plan Fails to Protect Athabasca River".

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Alberta's tar sands are soaking up too much water". Dogwood Initiative (2006-07-05).

- ↑ "'Conspiracy of silence' on tarsands, group says" CTV news accessed 2008-02-16

- ↑ "Tar won't stick" Edmonton Journal accessed 2008-02-16

- ↑ "Time for Ottawa to stop tiptoeing around Alberta oilsands sensibilities" Oil Week 2008-02-15 accessed 2008-02-16

- ↑ However, oil companies have done a poor job restoring former forest. Alberta Environment—Environmental Protection and Enhancement

- ↑ Troubled Waters, Troubling Trends May 2006, The Pembina Institute

- ↑ Environment Canada

- ↑ Athabasca river water management framework

- ↑ Environment Canada

- ↑ . Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers—Environmental Aspects of Oil Sands Development

- ↑ Alberta Environment—Athabasca River Water Management Framework

- ↑ Natural Resources Canada

- ↑ Pembina Institute Oil Sands Development and Climate Change (not a WP:RS)

- ↑ Alberta Energy Resources Board-Graphs and Data Section 2 Crude Bitumen

- ↑ Top 50 countries by greenhouse gas emissions Reuters

- ↑ "Carbon Capture and Storage" 30 November 2007.

- ↑ http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2008/aug/13/corporatesocialresponsibility.fossilfuels

- ↑ Mackenzie, Sir Alexander (1970). "The Journals and Letters of Alexander Mackenzie". Edited by W. Kaye Lamb. Cambridge: Hakluyt Society, pg. 129, ISBN 0521010349

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Hein, Francis J (2000). "Historical Overview of the Fort McMurray Area and Oil Sands Industry in Northeast Alberta" (PDF). Earth Sciences Report 2000-05. Alberta Geological Survey. Retrieved on 2008-02-17.

- ↑ "Oil Sands History". Unlocking the Potential of the Oil Sands. Syncrude (2006). Retrieved on 2008-02-17.

- ↑ Planning and Development Department (2006). "Municipal Census 2006" (PDF). Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo. Retrieved on 2008-02-06.

- ↑ "Urban Service Areas". Unincorporated Places. Alberta Population (2008). Retrieved on 2008-02-06.

- ↑ Andy Burrowes; Rick Marsh, Nehru Ramdin, Curtis Evans. "Alberta's Energy Reserves 2006 and Supply/Demand Outlook 2007-2016" (PDF). ST98. Alberta Energy and Utilities Board. Retrieved on 2008-04-12.

- ↑ Department of Energy, Alberta (June 2006). "Oil Sands Fact Sheets". Retrieved on 2007-04-11.

- ↑ Canada, Statistics (April 5, 2007). "Latest release from the labour force survey". Retrieved on 2007-04-11.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 NEB (June 2006). "Canada's Oil Sands Opportunities and Challenges to 2015: An Update" (PDF). National Energy Board of Canada. Retrieved on 2006-10-30.

- ↑ Nikiforuk, Andrew (2006-06-04). "The downside of boom: Alberta's manpower shortage", Canadian Business magazine. Retrieved on 2006-10-30.

- ↑ StatsCan (2006-09-14). "Study: The Alberta economic juggernaut". Statistics Canada. Retrieved on 2006-10-30.

- ↑ "Oil Sands". Alberta Energy. Alberta Government (2008). Retrieved on 2008-01-30.

- ↑ Franklin, Sonja; Gismatullin, Eduard (2007-12-05). "BP, Husky Energy Agree to Form Oil-Sands Partnerships", Bloomberg. Retrieved on 2007-12-12.

- ↑ Dutta, Ashok (2007-12-12). "ConocoPhillips aims high", Calgary Herald. Retrieved on 2007-12-12.

- ↑ Alberta, Employment, Immigration and Industry (December 2007). "Alberta Oil Sands Industry Update" (PDF). Government of Alberta. Retrieved on 2008-04-01.

- ↑ "Alberta Inventors and Inventions—Karl Clark". Retrieved on 2006-03-29.

- ↑ Gu G, Xu Z, Nandakumar K, Masliyah JH. (2002) "Influence of water-soluble and water-insoluble natural surface active components on the stability of water-in-toluene-diluted bitumen emulsion", Fuel, 81, pages 1859–1869.

- ↑ "Canada’s Energy Future: Reference Case and Scenarios to 2030" Pages 45-48 ISBN 978-0-662-46855-4

- ↑ "Questions and Answers". Canada's Oil Sands—Opportunities and Challenges to 2015: An Update. National Energy Board of Canada (2007-06-30). Retrieved on 2007-08-23.

- ↑ Long Lake Project

- ↑ "Operations—Athabasca Oil Sands—Long Lake Project—Project Overview". Nexen Inc.. Retrieved on 2006-03-29.

- ↑ "Nexen Nods Positive Reservoir Performance at Long Lake" Nexen, 17 July 2008

- ↑ Enbridge and PetroChina Sign Gateway Pipeline Cooperation Agreement | Business Wire | Find Articles at BNET

- ↑ Financial Post Article—Aboriginal implication in the project

- ↑ Oil Sands Projects Oilsands Discovery

- ↑ Synenco conference transcript

- ↑ Wojciech Moskwa (2007-04-27). "Statoil to buy North American Oil Sands for 2 bln". Financial Post. Retrieved on 2007-12-09.

External links

- Alberta’s Oil Sands: Key Issues and Impacts

- OnEarth Magazine » Canada's Highway to Hell

- Mud, Sweat and Tears—Guardian Newspaper, 2007

- Hugh McCullum, Fuelling Fortress America: A Report on the Athabasca Tar Sands and U.S. Demands for Canada's Energy (The Parkland Institute)--Executive SummaryDownload report

- Oil Sands History—Syncrude Canada

- Oil Sands Discovery Centre—Fort McMurray Tourism

- The Trillion-Barrel Tar Pit—Article from December 2004 Wired.

- Oil Sands Review—Sister publication to Oilweek Magazine

- Alberta's Oil Sands—Alberta Department of Energy

- Alberta's Reserves 2005 and Supply/Demand Outlook 2006-2015—Alberta Energy and Utilities Board 2006-06-15

- Canada's Oil Sands—Opportunities and Challenges to 2015: An Update—June 2006—National Energy Board of Canada

- Oilsands overview- Canadian Centre for Energy Information

- Alberta Plan Fails to Protect Athabasca River

- Megaprojects

- "Energy Statistics Handbook" (February 2008) Statistics Canada ISSN 1496-4600