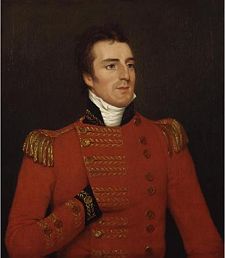

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office 17 November 1834 – 9 December 1834 |

|

| Monarch | William IV |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Melbourne |

| Succeeded by | Sir Robert Peel, Bt |

| In office 22 January 1828 – 16 November 1830 |

|

| Monarch | George IV William IV |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Goderich |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Grey |

|

|

|

| Born | c. 1 May 1769 Possibly Dublin or County Meath |

| Died | 14 September 1852 (aged 83) Walmer, Kent |

| Political party | Tory |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | British Army |

| Years of service | 1787–1852 |

| Rank | Field Marshal |

| Commands | Commander-in-Chief of the Forces |

| Battles/wars | Fourth Anglo-Mysore War, Second Anglo-Maratha War, Peninsular War, Waterloo campaign |

Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, KG, KP, GCB, GCH, PC, FRS (c. 1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852), was an Anglo-Irish soldier and statesman. He was one of the leading military and political figures of the nineteenth century.

Born in Ireland to a prominent Ascendancy family, he was commissioned an ensign in the British Army in 1787. Serving in Ireland as aide-de-camp to two successive Lords Lieutenant of Ireland he was also elected as member of Parliament in the Irish House of Commons. A colonel by 1796, Wellesley saw action in the Netherlands and later India where he fought in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War at the Battle of Seringapatam. He was later appointed Governor of Seringapatam and Mysore.

Wellesley soon rose to prominence as a General during the early Napoleonic Wars. In the Peninsular Campaign he led the Allied forces to victory against the French and after the Battle of Vitoria in 1813, promoted to the rank of field marshal. Serving as the ambassador to France following the exile of Napoleon in 1814, during which time he was granted a Dukedom, he returned to fight Napoleon's forces during the Hundred Days in 1815. This culminated at the Battle of Waterloo, which saw the defeat of the French Emperor and a decisive coalition victory.

An opponent of parliamentary reform, he was given the epithet the "Iron Duke" because of the iron shutters he had fixed to his windows to stop the pro-reform mob from breaking them. He was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom under the Tory party and oversaw the passage of Catholic Relief Act 1829 (See Catholic emancipation). He continued as Prime Minister until 1830 and again served briefly in 1834. Although unable to prevent the passage of the Reform Act of 1832 he continued as one of the leading figures in the House of Lords until his retirement. He remained Commander-in-Chief of the British Army until his death.

Contents |

Early life

The earliest mention of the Wellesley family can be dated back to the year of 1180. It places Wellington’s ancestry among the conquering elite of the Norman invasion in 1066 as the family had been granted lands to the south of Wells around a settlement still known today as Wellesley Farm. As well as having Wellesley ancestors, "Wesley" was inherited from the childless rich husband of an aunt when, in 1728, Wellington's patrilineal grandfather Garret Colley, a landlord who lived at Rahin near Carbury, County Kildare, changed his surname to Wesley.[1] The Colleys had lived in that part of Kildare since the Norman Invasion of Ireland in 1169–72. In 1917 the Kildare historian Lord Walter FitzGerald mentioned the: "... Elizabethan Castle which since 1588 has been in the possession of the family of Cowley or Colley, from whom the Dukes of Wellington are descended in the direct male line".[2]

Wellington was born The Honourable Arthur Wesley, the fourth son (but third of five surviving sons) to Garret Wesley, 1st Earl of Mornington, and Anne, the eldest daughter of Arthur Hill, Viscount Duncannon, most likely at 24 Upper Merrion Street, Dublin, opposite what was then the Royal College of Science (now Government Buildings).[3] His biographers follow the contemporary newspaper evidence in ascribing his birthdate to 1 May 1769.[4][5] Various other places have been assigned by tradition; ranging from Mornington House, Dublin (as his father claimed), to the now-vanished house next door, to the Dublin packet boat, as well as the family estate of Athy, which the Duke apparently put on the 1851 census, now burnt.[6]

Born as a member of the Protestant Ascendancy, he was sensitive to his Irish birth, once stating that "being born in a stable does not make one a horse."[7] He spent most of his childhood at his family's two homes, the first a large house in Dublin and the second, Dangan Castle, 5 km north of Summerhill on the Trim road in County Meath, part of the Province of Leinster.[8] In 1781 Arthur's father died and his eldest brother Richard inherited his father's earldom.[9] Two of his other brothers were later raised to the peerage as Baron Maryborough and Baron Cowley.

The family's surname was changed from Wesley to "Wellesley" in 1798.[10]

Education

After studying at the diocesan school in Trim when at Dangan, and at Mr. Whyte's Academy when in Dublin, and at Brown's School in Chelsea when in London, he then went to Eton where he studied from 1781 to 1784.[9] However a lack of success there, combined with a shortage of family funds from his father's death, led to a move to Brussels in Belgium with his mother in 1785.[11] Until his early twenties Arthur continued to show little signs of distinction and his mother grew increasingly concerned at his idleness, stating, "I don't know what I shall do with my awkward son Arthur".[11]

A year later Arthur was enrolled in the French Royal Academy of Equitation in Angers, where he progressed significantly, becoming a good horseman and learning French (which was to prove very useful in later years).[12] Upon returning to England in late 1786 he astonished his mother with his improvement.[13]

Early career

Despite his new promise he had yet to find a job and his family was still short of money, so upon the advice of his mother, his brother Richard asked his friend the Duke of Rutland (then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland) to consider Arthur for a commission in the army.[13] Soon after, on the 7 March 1787 he was gazetted ensign in the 73rd Regiment of Foot.[14] In October, with the assistance of his brother, he was assigned as aide-de-camp, on ten shillings a day (twice his pay as an ensign), to the new Lord Lieutenant of Ireland Lord Buckingham.[14] He was also transferred to the new 76th Regiment forming in Ireland and on Christmas day, 1787, was promoted to Lieutenant.[14] During his time in Dublin his duties were mainly social; attending balls, entertaining guests and providing advice to Buckingham. While in Ireland, he over extended himself in borrowing due to his occasional gambling, but in his defence stated that "I have often known what it was to be in want of money, but I have never got helplessly into debt".[15]

Two years later, in June 1789 he transferred to the 12th Light Dragoons, still as a lieutenant and according to his biographer, Richard Holmes he also dipped a reluctant toe into politics.[15] Shortly before the general election of 1789, he went to the rotten borough of Trim to speak against the granting of the title Freeman of Dublin to the parliamentary leader of the Irish nationalist movement, Henry Grattan.[16] Succeeding, he was later nominated and duly elected as a member of Parliament for Trim in the Irish House of Commons.[17] Because of the limited suffrage at the time, he sat in a parliament, where at least two-thirds of the members owed their election to the landowners of less than a hundred boroughs.[17] Wellesley continued to serve at Dublin Castle, voting with the government in the Irish parliament over the next two years and in 1791 he became a Captain and was transferred to the 18th Light Dragoons.[17]

It was during this period that he grew increasingly attracted to Kitty Pakenham, the daughter of the Earl of Longford.[18] She was described as being full of 'gaiety and charm'.[19] Seeking permission to marry her in 1793 he was turned down by her brother, the new Earl of Longford who considered Wellesley to be a young man, in debt, with very poor prospects.[20] An inspiring amateur musician, Wellesley devastated by the rejection, burnt his violins in anger, and decided he wished to pursue his military career.[21] Gaining further promotion (largely by purchasing his rank, which was common in the British Army at the time), he became a Major in the 33rd Regiment in 1793.[18] A few months later, in September, his brother lent him more money and with it he purchased a lieutenant colonelcy in the 33rd.[22]

Netherlands

In 1793, the Duke of York was sent to Flanders in command of the British contingent of an allied force destined for the invasion of France. In 1794 the 33rd regiment was sent to join the force and Wellesley set sail from Cork for Flanders in June, destined for his first real battle experience.[22] During the campaign he rose to command a brigade and in September Wellesley's unit came under fire just east of Breda, just before the Battle of Boxtel.[23] For the latter part of the campaign, during the winter, his unit defended the line of the Waal River, during which time he became ill for a while, owing to the damp environment.[24] Though the campaign was to prove unsuccessful, with the Duke of York's force returning in 1795, Wellesley was to learn several valuable lessons, including the use of steady fire lines against advancing columns and of the merits of supporting sea-power.[23] He concluded that many of the campaign's blunders were due to the faults of the leaders and the poor organisation at Headquarters.[25] He remarked later of his time in the Netherlands that "At least I learned what not to do, and that is always a valuable lesson."[25]

Returning to England in March 1795 he was returned as a member of Parliament for Trim for a second time.[26] He hoped to be given the position of secretary of war in the new Irish government but the new lord-lieutenant, Lord Camden was only able to offer him the post of Surveyor-General of the Ordnance.[26] Declining the post he returned to his regiment, now at Southampton preparing to set sail for the West Indies. After seven weeks at sea, a storm forced the fleet back to Poole, England.[26] The 33rd was given time to convalesce and a few months later, Whitehall decided to send the regiment to India. Wellesley was promoted full colonel by seniority a few weeks later and in 1796 set sail for Calcutta with his regiment.[27]

India

- Further information: Fourth Anglo-Mysore War and Second Anglo-Maratha War

Arriving in Calcutta in February 1797 he spent several months there, before being sent on a brief expedition to the Philippines, where he established a list of new hygiene precautions for his men to deal with the unfamiliar climate.[28] Returning in November to India, he learnt that his elder brother Richard, now known as Lord Mornington, had been appointed as the new Governor-General of India.[29] As part of the campaign to extend the rule of the British East India Company, the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War broke out in 1798 against the Sultan of Mysore, Tippoo Sultan.[30] Arthur's brother Richard, ordered that an army force be sent to capture Seringapatam and defeat Tippoo. Under the command of General Harris, some 24,000 troops were dispatched to Madras (to join an equal force being sent from Bombay in the west).[31] Arthur and the 33rd sailed to join them in August.[32]

It was at this time that his family changed the spelling of their surname to Wellesley - up to this time he was still known as Wesley - which his oldest brother considered the ancient and proper spelling.[29]

After extensive and careful logistic preparation (that would become one of Wellesley's main attributes) the 33rd left with the main force in December and travelled across 250 miles (400 km) of jungle from Madras to Mysore.[33] On account of his brother, during the journey, Wellesley was given an additional command, that of chief advisor to the Nizam of Hyderabad's army (sent to accompany the British force).[31] This position was to cause friction amongst many of the senior officers (some of whom were senior to Wellesley).[34] Much of this friction was put to rest after the battle of Malavelly, some 20 miles (32 km) from Seringapatam, in which Harris's army attacked a large part of the sultan's army. During the battle, Wellesley led his men, in a line of battle of two ranks, against the enemy to a gentle ridge and gave the order to fire.[35] After an extensive repeat of volleys, followed by a bayonet charge, the 33rd, in conjunction with the rest of Harris's force, forced Tippoo's infantry to retreat.[35]

Srirangapatna and Mysore

Immediately after their arrival at Seringapatam on the 5th, the Battle of Srirangapatna commenced and Wellesley was ordered to lead a night attack on the village of Sultanpettah, adjacent to the fortress to clear the way for the artillery.[36] Because of the enemy's strong defensive preparations and the darkness (with resulting confusion), the attack failed, with 25 casualties. (Wellesley himself suffered a minor injury to his knee from a spent musket-ball).[36][37] Although they would reattack successfully the next day (with time to scout ahead the enemy's positions) the affair had an impact on Wellesley.[36] He resolved "never to attack an enemy who is preparing and strongly posted, and whose posts have not been reconnoitred by daylight".[36]

A few weeks later, after extensive artillery bombardment, a breach was opened in the main walls of the fortress of Seringapatam.[38] An attack led by Major-General Baird secured the fortress. Wellesley secured the rear of the advance, posting guards at the breach and then stationing his regiment at the main palace.[38] After hearing news of the death of the Tippoo Sultan, Wellesley was the first at the scene to confirm his death, checking his pulse.[38] Over the coming day, Wellesley grew increasingly concerned over the lack of discipline amongst his men, who were drinking and pillaging the fortress and city.[39] To restore order, several soldiers were flogged and four hanged.[36]

After battle and the resulting end of the war, the main force under General Harris left Seringapatam and Wellesley (aged 30) stayed behind to command the area as the new Governor of Seringapatam and Mysore, taking residence within the sultan's summer palace.[40] He reformed the tax and justice systems in his province to maintain order and prevent bribery. He also hunted down the mercenary King Dhoondiah Waugh, who had escaped from prison in Seringapatam during the battle. Wellesley, with command of four regiments, defeated Dhoondiah's larger rebel force, along with Dhoondiah himself who was killed in the battle.[41] Magnanimous in victory, he paid for the future upkeep of Dhundia's orphaned son.[42]

During his time in India Wellesley was ill for a considerable time, first with severe Diarrhea (from the water) and then with a fever, followed by a terrible skin infection due to Trichophyton.[43] However he received good news when in September 1802 he learnt that he had been promoted to the rank of Major-General.[44][45] He remained at Mysore until November when he was sent to command an army in the Second Anglo-Maratha War.[44]

Second Anglo-Maratha War

Wellesley decided that he must act boldly to defeat the numerically larger force of the Maratha Empire (as he concluded a long defensive war would ruin his army).[46] With the logistical assembly of his army complete (24,000 men in total) he gave the order to break camp and attack the nearest Maratha fort on the 8 August 1803.[44][46] The fort surrendered on the 12th after an infantry attack had exploited an artillery-made breach in the wall. With the fort now in British control Wellesley was able to extend control southwards to the river Godavari.[47]

Splitting his army into two forces, to pursue and locate the main Marathas army, (the second force, commanded by Colonel Stevenson was far smaller) Wellesley was preparing to rejoin his forces on the 24 September. However his intelligence reported the location of the Marathas main army, between two rivers near Assaye.[48] If he waited for the arrival of his second force, the Marathas would be able to mount a retreat, so Wellesley decided to launch an attack immediately.[48] On the 23 September, Wellesley led his forces over a ford in the river Kaitna and the Battle of Assaye commenced.[48] After crossing the ford the infantry was reorganised into several lines and advanced against the Maratha infantry. Wellesley ordered his cavalry to exploit the flank of the Maratha army just near the village.[48] During the battle Wellesley himself was under fire; two of his horses were shot from under him and he had to mount a third.[48] At a crucial moment, Wellesley regrouped his forces and ordered Colonel Maxwell (later killed in the attack) to attack the eastern end of the Maratha position while Wellesley himself directed a renewed infantry attack against the centre.[48] An officer in the attack wrote of the importance of Wellesley's personal leadership:"The general was in the thick of the action the whole time... Until our troops got the order to readvance, the fate of the day seemed doubtful."[49] With some 6,000 Marathas killed or wounded, the enemy routed (though Wellesley's force was in no condition to pursue), at a cost of 1,584 British killed or wounded.[48] Wellesley was troubled by the loss of men and remarked that he hoped "I should not like to see again such loss as I sustained on the 23 September, even if attended by such gain".[48] However years later he remarked that 'Assaye' was the best battle he ever fought.[48]

However despite the damage done to the Maratha army, the battle did not end the war.[50] A few months later in November, Wellesley attacked a larger force near Argaum, leading his army to victory again, with an astonishing 5,000 enemy dead at the cost of only 361 British casualties.[50] A further successful attack at the fortress at Gawilghur, combined with the victory of General Lake at Delhi forced the Maratha to a peace settlement (not concluded until a year later).[51] His biographer, Richard Holmes remarked that his experiences in India had an important influence on his personality and military tactics, teaching him much about military matters that would prove vital to his success in the Peninsular War.[52] These included his strong sense of discipline through drill and order.[52] More importantly he had established a high regard for the acquisition of intelligence through scouts and spies.[52] His personal tastes had also developed, including dressing himself in white trousers, a dark tunic, with Hessian boots and black cocked hat (that would later become synonymous as his style).[52]

Return to England

Wellesley had grown tired of his time in India remarking "I have served as long in India as any man ought who can serve anywhere else."[53] In June 1804 he applied for permission to return home and as a reward for his service in India, in September he was made a Knight of the Bath.[53] While in India Wellesley had amassed a fortune of £42,000 (considerable at the time), mainly consisting of prize money from his campaign.[53] When his brother's term as Governor-General of India ended in march 1805, the brothers returned together to England (ironically Arthur was to stop on his voyage at the little island of Saint Helena and stayed in the same building to which Napoleon I of France would later be exiled).[54] After returning home, the Wellesleys were forced to defend their employment of the British forces in India. However Wellesley received good news, when, owing to his new title and status, he was given permission to marry Kitty Pakenham (from her family). She became his wife in April 1806.[55]

Wellesley served in the abortive Anglo-Russian expedition to north Germany in 1805. After Austerlitz, the forces went home having accomplished nothing. Junior command in an expedition to Denmark in 1807 led to Wellesley's promotion to lieutenant general. Meanwhile, he was elected Tory member of Parliament for Rye for six months in 1806. A year later, he was elected MP for Newport on the Isle of Wight, a constituency he would represent for two years. He served as Chief Secretary for Ireland for two years. In April 1807, he became a privy counsellor. However his political life came to an abrupt halt when he sailed to Europe to participate in the action against French forces in Iberia.

Peninsular War

It was in the following turbulent years that Wellesley won his place in history through caution, repeated use of the reverse slope defence and using line formation against the French columns. Since 1789, France had been embroiled in the French Revolution. Napoleon seized its government in 1799, and reached the heights of power in Europe, eventually ordering the invasion of Spain and Portugal in 1807. The next year, Wellesley was preparing to command an expedition to Venezuela in collaboration with Latin American patriot Francisco de Miranda, when the Spanish revolt began the Peninsular War and he was sent to Portugal instead.[56] Wellesley defeated the French at the Battle of Roliça and the Battle of Vimeiro in 1808 but he was superseded in command immediately after the latter battle. General Dalrymple insisted on associating the available government minister (Wellesley) with the controversial Convention of Sintra, which stipulated that the British Royal Navy would transport the French army out of Lisbon with all their loot. Wellesley was recalled to Britain to face a Court of Enquiry. He had agreed to sign the preliminary Armistice, but had not signed the Convention, and was cleared.[57]

Meanwhile, Napoleon himself entered Spain with his veteran troops to put down the revolt, and the new commander of the British forces in the Peninsula, Sir John Moore, died during the Battle of Corunna, January 1809.

Although the war was not going particularly well, it was the one place where the British and the Portuguese (their oldest ally) had managed to put up a fight against France and her allies. (Compare it to the disastrous Walcheren expedition, which was typical of the mismanaged British operations of the time.) Wellesley submitted a memorandum to Lord Castlereagh on the defence of Portugal, stressing its mountainous frontiers and advocating Lisbon as the main base because the Royal Navy could make it impregnable. Castlereagh and the cabinet approved the memo, and appointed him head of all British forces in Portugal, raising their number from 10,000 to 26,000 men.

Quickly reinforced, Wellesley took the offensive in April 1809. In the Second Battle of Porto, he crossed the Douro river in a brilliant daylight coup de main, and routed the French troops in Porto. He then joined with a Spanish army under Cuesta in operations against Madrid. They meant to attack Marshal Victor, but Napoleon's brother, King Joseph Bonaparte, reinforced Victor first, and the French attacked and lost at the Battle of Talavera. For this, Wellesley was ennobled as Viscount Wellington of Talavera and of Wellington.[58] With Marshal Soult threatening their rear, the British were compelled to retreat to Portugal. Deprived of the supplies promised by the Spanish throughout the campaign and not told of Soult's movement, Wellington never again relied on Spanish promises or resources.

In 1810, a newly enlarged French army under Marshal André Masséna invaded Portugal. British opinion both at home and in the army was uniformly gloomy – they must evacuate Portugal. But Wellington first slowed the French down at Buçaco, then blocked them from taking the Lisbon peninsula by his magnificently constructed earthworks, the Lines of Torres Vedras, brilliantly assembled in complete secrecy, and with flanks guarded by the Royal Navy. The baffled and starving French invasion forces retreated after six months. Wellington followed and, in several skirmishes and the Battle of Sabugal, drove them out of Portugal, except for a small garrison at Almeida, which was placed under siege.

In 1811, Masséna returned towards Portugal to relieve Almeida, but Wellington narrowly defeated the French at the battle of Fuentes de Oñoro. Meanwhile, Wellington's subordinate, Viscount Beresford, fought Soult's 'Army of the South' to a bloody standstill at the Battle of Albuera. In May, Wellington was promoted to general for his services. The French abandoned Almeida, but retained the twin Spanish fortresses of Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz, the 'Keys' guarding the roads through the mountain passes into Portugal.

In 1812, Wellington finally captured Ciudad Rodrigo by pouncing as the French went into winter quarters and storming it before they could react. Moving south quickly, he besieged the fortress of Badajoz for a month and captured it in one bloody night. On viewing the aftermath of the Storming of Badajoz, Wellington lost his composure, breaking down and crying at the sight of the carnage in the breaches.[59]

His army now was a British force reinforced in all divisions by units of the resurgent Portuguese army, rebuilt by Beresford. Campaigning in Spain, he routed the French at the Battle of Salamanca, taking brilliant advantage of a minor French mispositioning. (This was the first time a French army of 50,000 had been routed since 1799.) The victory liberated the Spanish capital of Madrid. As reward, he was created Earl and then Marquess of Wellington and given command of all Allied armies in Spain.[60]

He attempted to take the vital fortress of Burgos, which linked Madrid to France, but failed due to a lack of siege equipment. The French meanwhile abandoned Andalusia, and combined those troops with their other armies to put the British forces into a precarious position. Wellington skilfully withdrew his army and, joining with the smaller corps commanded by Rowland Hill, retreated to Portugal. (Marshal Soult actually held a numerical advantage over Wellington in November, but hesitated to attack, so fearful had he become of the British commander.) Still, the victory at Salamanca had forced the French to withdraw from southern Spain, and the temporary loss of Madrid irreparably damaged the prestige of the pro-French puppet government.

In 1813, Wellington led a new offensive, against the French line of communications. He struck through the hills north of Burgos, and unexpectedly switched his supply line from Portugal to Santander on Spain's north coast. He personally led a small force in a feint against the French centre, while the main army (commanded by Sir Thomas Graham) looped around the French right, leading to the French abandoning Madrid and Burgos. Continuing to outflank the French lines, Wellington caught up with and smashed the army of King Joseph Bonaparte in the Battle of Vitoria, for which he was promoted to field marshal.[61] This battle became the subject of Beethoven's work Wellington's Victory. However, the British troops broke discipline to loot the abandoned French wagons instead of pursuing the beaten foe. This gross abandonment of discipline caused an enraged Wellington to write in a dispatch to Earl Bathurst, "We have in the service the scum of the earth as common soldiers".[62]

After taking the small fortresses of Pamplona and San Sebastián, and winning the battles of the Pyrenees, Bidassoa and Nivelle over Soult's reorganised French army, Wellington invaded southern France. After success at the Battle of the Nive, he isolated the fortress of Bayonne and defeated Soult at the battles of Orthez and Toulouse. Immediately after Soult evacuated the latter city, news arrived of Napoleon's defeat and abdication. Napoleon was later exiled to the island of Elba.

Hailed as the conquering hero, Wellington was created Duke of Wellington, a title still held by his descendants. (Since he did not return to England until the Peninsular War was over, he was awarded all his patents of nobility in a unique ceremony lasting a full day.) He was soon appointed ambassador to France, then took Lord Castlereagh's place as First Plenipotentiary to the Congress of Vienna, where he strongly advocated allowing France to keep its place in the European balance of power. On 2 January 1815, the title of his Knighthood of the Bath was converted to Knight Grand Cross upon the expansion of that order.

Despite his successes in the peninsular campaign, however, an alternative--if minority--view of his skill as a commander relative to that of his opponents is provided by A.G. Macdonell:

Probably no general in history has ever had such an easy time as Wellington had [in the Iberian peninsula]. Working on interior lines, with a mercenary army, in a country where every peasant and priest was at once an ally, a source of information, and an active assassin, with a constant flow of supplies from England, and with the complete command of the sea, the Duke of Wellington had the game in his hands, and yet it took him nearly six years to advance from Lisbon to the Pyrenees.[63]

Battle of Waterloo

On 26 February 1815, Napoleon escaped from Elba and returned to France. Regaining control of the country by May, he faced a renewed alliance against him.[64] Wellington left Vienna for what became known as the Waterloo Campaign. He arrived in Belgium to take command of the British-German army and their allied Dutch-Belgians, all stationed alongside the Prussian forces of Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. The French invaded Belgium, defeated the Prussians at Ligny, and fought an indecisive battle with Wellington at the Battle of Quatre Bras. These events compelled the Anglo-Allied army to retreat to a ridge on the Brussels road, just south of the small town of Waterloo. Two days later, on 18 June, came the famous Battle of Waterloo. After an all-day fight, with the Anglo-Allies standing firm against French shelling and cavalry charges, the Prussian Army under Blücher arrived, some of them reinforcing the left of Wellington's line and others engaging the French right flank at Plancenoit. The French Imperial Guard was then dramatically repulsed by British volley fire, and Napoleon's army routed in panic.

Although Wellington's army held off the French attacks for several hours before Blücher's arrival, there is still debate about whether the Allied victory would have been so crushing had it not been for the arrival of the Prussian Army. It should also be remembered that a third of Napoleon's army, under Marshal Grouchy, were engaged against the Prussians at Wavre some miles to the east. Considering these factors, and the fact that around a third of Wellington's army were German, one German historian in the 1990s went so far as to describe Waterloo as a "German Victory". On 22 June, the French Emperor abdicated once again, and was transported by the British to distant St Helena. The battle of Waterloo was canonised within a generation as one of The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World.

When he finally encountered Napoleon in 1815, Wellington commanded an Anglo-German-Netherlandish army consisting of a mere 25,000 troops trained to British standards—the rest were poorly trained soldiers taken from Dutch and Nassau forces (some had even fought for Napoleon before). (Many of the best British troops had been sent to America, to finally end the War of 1812 there.)

Much fuss is made about Napoleon's decision to send 33,000 troops under Marshal Grouchy to intercept the Prussians, but—having defeated Blücher at Ligny on 16 June and forced the Allies to retreat in divergent directions—Napoleon was strategically sound, knowing himself unable to beat the combined Allied forces on one battlefield. Wellington's comparable strategic gamble was to leave 17,000 troops plus artillery at Hal, north-west of the Mont Saint Jean. The potential benefits of this decision were not only protection against Napoleon's attempt to turn his right flank, but to provide Wellington with a reserve with which to fight again the following day should the action on 18 June prove inconclusive.

Napoleon's tactics have been criticised as lacking in the brilliance he exhibited earlier in his career, but given the forces arrayed against him (not to mention the Russians and Austrians mobilising in the east) the choices confronting him, and his responses to them, were brutally clear. Having defeated the Prussians at Ligny on 16 June, and having compelled Wellington's forces to retreat to maintain contact with the Prussians, Napoleon's aim was simple and indispensable if he was to have any chance of victory and the possibility of a peace with Austria and Russia—keep the Prussians and the Allies from joining on the same battlefield.

Napoleon could not attack Wellington's right flank, partly because of the rearguard stationed at Hal, and ultimately because his wish was to divide Wellington and Blücher rather than drive them together. His plan was simple but effective—to pin Wellington's right with overwhelming cannon fire and an attack on Hougoumont, drawing reinforcements away from Wellington's centre-left position, then shatter this position with an all-out infantry assault in the column formation which had always been so successful with other European armies earlier in Napoleon's career.

In fact Hougoumont held out, only modestly reinforced by Wellington, and the great infantry attack by the French was destroyed by Allied cavalry, albeit in poorly controlled charges which resulted in many losses to themselves and to Napoleon's Polish lancers. Napoleon's only option now was an all-out assault on the Allied centre, leaving no effective force for the Prussians to make contact with. Wellington's reorganising of his line was taken as the prelude to retreat, and now waves of French cavalry attacked the Allies, driving them into scattered defensive groupings ('squares') at which point a combined attack by French infantry and artillery, firing point-blank into the squares, would probably have caused the desired devastation.

At this point Napoleon was inferior as tactician to his undoubted genius as strategist - coordination of the various branches of the French army at Waterloo was haphazard throughout, and at this moment decisively lacking. The squares held out, the spaces between them protected by what remained of the Allied cavalry, and gradually the French cavalry assault, obliged to charge uphill through muddy terrain criss-crossed by sunken roads, petered out. The Prussians were now driving in Napoleon's outposts, and whatever had happened to Grouchy's force of thirty thousand (defeat, or the ever-present fear of treason in the ranks), it was now clear that the Prussians had fought their way through to the battlefield and were about to make a decisive contribution.

Napoleon made one last attempt to smash Wellington's centre before his two enemies could achieve any kind of linkage, and at about six in the evening the farmhouse of La Haye Sainte, lynch-pin of the Allied front, was finally taken. Once again, Wellington redrew the remnants of his front and prepared for the final assault, now knowing that the dark uniforms visible in the distance were the forces of Blücher rather than Grouchy. Napoleon now sent forward the Imperial Guard, always held in reserve to provide the killer blow in any battle, branching out in a two-pronged attack to finish off what Napoleon believed to be an Allied army on the point of annihilation. Wellington had prepared, in effect, a large-scale ambush for the possibly over-confident Guard, who ran into surprise counter-attacks and crossfire from British infantry as steady and well-disciplined as ever, hidden behind slopes or in what was left of the crops on this most agricultural of battlefields. Unprepared, and perhaps demoralised by the French failure to carry the day, the Guard faltered and then retreated, an event unthinkable in Napoleonic warfare, and one which triggered instant French panic.

Wellington finally ordered an advance of the Allied line as the Prussians were driving in the French positions to the east, and what remained of the French army abandoned the field in disorder. Wellington and Blücher met at the inn of La Belle Alliance, on the north–south road which bisected the battlefield, and it was agreed that the relatively rested Prussians should pursue the retreating French army back to France.

In spite of many later attempts, some of them made to him in person, to suggest that by his own military standards Waterloo had been a bit of a mess, Wellington always maintained his strategy had been clear from the beginning - to hold his position against everything that Napoleon could bring against it, and when the moment was right, to counter-attack the positions of the French with the aim of ending the battle, a strategy which he had achieved (having only agreed to make a stand on the Mont Saint Jean on condition the Prussians would march west to link up with him, and only receiving information late in the day that the Prussians were in fact making inroads on the French right). Waterloo may not have been a 'good' battle, but it marked the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

Statesman

Politics beckoned once again in 1819, when Wellington was appointed Master-General of the Ordnance in the Tory government of Lord Liverpool. In 1827, he was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the British Army.

Prime Minister

Along with Robert Peel, Wellington became one of the rising stars of the Tory party, and in 1828 he became Prime Minister.

During his first seven months as Prime Minister he chose not to live in the official residence at 10 Downing Street, finding it too small. He relented and moved in only because his own home, Apsley House, required extensive renovations. During this time he was largely instrumental in the foundation of King's College London.[65]

As Prime Minister, Wellington was the picture of the arch-conservative, fearing that the anarchy of the French Revolution would spread to England. The highlight of his term was Catholic Emancipation; the granting of almost full civil rights to Catholics in the United Kingdom. The change was forced by the landslide by-election win of Daniel O'Connell, an Irish Catholic proponent of emancipation, who was elected despite not being legally allowed to sit in Parliament. The Earl of Winchilsea accused the Duke of having "treacherously plotted the destruction of the Protestant constitution". Wellington responded by immediately challenging Winchilsea to a duel. On 21 March 1829, Wellington and Winchilsea met on Battersea fields. When it came time to fire, the Duke took aim and Winchilsea kept his arm down. The Duke fired wide to the right. Accounts differ as to whether he missed on purpose; Wellington, noted for his poor aim, claimed he did, other reports more sympathetic to Winchilsea claimed he had aimed to kill. Winchilsea did not fire, a plan he and his second almost certainly decided upon before the duel.[66] Honour was saved and Winchilsea subsequently wrote Wellington an apology.[67] In the House of Lords, facing stiff opposition, Wellington spoke for Catholic emancipation, giving one of the best speeches of his career.[68] He had grown up in Ireland, and later governed it, so he knew firsthand of the misery of the Catholic communities there. The Catholic Relief Act 1829 was passed with a majority of 105. Many of the Tories voted against the Act, and it passed only with the help of the Whigs.

The epithet "Iron Duke" originates from his period of Prime Minister, during which he experienced an extremely high degree of personal and political unpopularity. His residence at Apsley House was a target of window-smashers and iron shutters were installed to mitigate the damage. It was this, rather than his characteristic resolute constitution, that earned him the epithet of "The Iron Duke".

Wellington's government fell in 1830. In the summer and autumn of that year, a wave of riots (the Swing Riots) swept the country. The Whigs had been out of power for all but a few years since the 1770s, and saw political reform in response to the unrest as the key to their return. Wellington stuck to the Tory policy of no reform and no expansion of the franchise, and as a result lost a vote of no confidence on 15 November 1830. He was replaced as Prime Minister by Earl Grey.

Wellington and the Reform Act

The Whigs introduced the first Reform Act, but Wellington and the Tories worked to prevent its passage. The bill passed in the House of Commons, but was defeated in the House of Lords. An election followed in direct response, and the Whigs were returned with an even larger majority. A second Reform Act was introduced, and defeated in the same way, and another wave of near insurrection swept the country. During this time, Wellington was greeted by a hostile reaction from the crowds at the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. The Whig Government fell in 1832, but Wellington was unable to form a Tory Government – amongst other reasons because of a run on the Bank of England – leaving King William IV no choice but to restore Earl Grey to the premiership. Eventually the bill passed the House of Lords after the King threatened to fill that House with newly created Whig peers if it were not. Though the Bill passed, Wellington was never reconciled to the change; when Parliament first met after the first election under the widened franchise, Wellington is reported to have said "I never saw so many shocking bad hats in my life."

Caretaker Prime Minister and Member of Peel's Cabinet

During this time Wellington was gradually superseded as leader of the Tories by Robert Peel, whilst the party evolved into the Conservatives. When the Tories were brought back to power in 1834, Wellington declined to become Prime Minister, and Peel was selected instead. However, Peel was in Italy, and for three weeks in November and December 1834, Wellington acted as a caretaker, taking the responsibilities of Prime Minister and most of the other ministries. In Peel's first cabinet (1834–1835), Wellington became Foreign Secretary, while in the second (1841–1846) he was a Minister without Portfolio and Leader of the House of Lords.

Retirement and death

Wellington retired from political life in 1846, although he remained Commander-in-Chief of the Forces, and returned briefly to the spotlight in 1848 when he helped organise a military force to protect London during that year of European revolution. The Conservative Party had split over the Repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, with Wellington and most of the former Cabinet still supporting Robert Peel, but most of the MPs supporting the new leader Lord Derby. Early in 1852 Wellington gave Derby's first government its nickname by shouting "Who? Who?" as the list of inexperienced Cabinet Ministers was read out in the House of Lords.

Wellington died later in 1852 at Walmer Castle (his honorary residence as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, which he enjoyed and at which he hosted Queen Victoria). Although in life he hated travelling by rail, his body was then taken by train to London, where he was given a state funeral – one of only a handful of British subjects to be honoured in that way (other examples are Lord Nelson and Winston Churchill) – and the last heraldic state funeral to be held in Britain. At his funeral there was hardly any space to stand because of the number of people attending, and the effusive praise given him in Tennyson's "Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington" attests to his stature at the time of his death. He was buried in a sarcophagus of luxulyanite in St Paul's Cathedral next to Lord Nelson.

Personality

Traits

Wellington set a gruelling pace of work. He rose early – he "couldn't bear to lie in" once awake – and usually slept for six hours or less. Even when he returned to civilian life after 1815, he slept in a camp bed, reflecting his lack of regard for creature comforts. General Miguel de Álava complained that Wellington said so often that the army would march "at daybreak" and dine on "cold meat", that he began to dread the two phrases. While on campaign, he seldom ate anything between breakfast and dinner. During the retreat to Portugal in 1811, he subsisted (to the despair of his staff, who dined with him) entirely on "cold meat and bread". He was however renowned for the excellent quality of the wine he drank and served, often drinking a bottle with his dinner – not a great quantity by the standards of his day.

He was very partial to high-technology and mechanical gadgets, being one of the first British soldiers to employ shrapnel shells and congreve rockets (although he was disappointed with the latter, as they had very poor guidance devices). He also employed a full time officer to decrypt intercepted French messages. On the other hand, although meticulously organised, his supply trains comprised pack mules and ox carts (with ungreased axles) (plus cargo boats if rivers could be used).

He rarely showed emotion before his intellectual or social inferiors. However, Álava was a witness to the following scene. Just before the Battle of Salamanca, Wellington was eating a chicken leg while observing the manoeuvres of the French army though a spyglass. He spotted an overextension in the French left flank, and realising that he could launch a successful attack there, threw the drumstick in the air and shouted "Les français sont perdus!" ("The French are lost!"). Also, after the Battle of Toulouse, when an aide brought him news of Napoleon's abdication, he spun around on his heels, clicking his fingers in a sort of impromptu flamenco dance.[69]

Despite his famous stern countenance and iron-handed discipline, Wellesley deeply cared for his men; he refused to pursue the French after the battles of Porto and Salamanca, because of the inevitable cost to his army in pursuing a broken enemy through rough terrain. In addition, the only times he ever showed grief in public was over the lives of his men: after the disastrously costly storming of Badajoz, he cried at the sight of British dead in the breaches. In this context, his famous letter after the Battle of Vitoria calling them the 'scum of the earth' can be seen to be fuelled as much by disappointment at their breaking ranks as by anger.

As a soldier

Wellington has often been portrayed as a defensive general, even though many, perhaps most, of his battles were offensive (Argaum, Assaye, Oporto, Salamanca, Toulouse, Vitoria). But for most of the Peninsular War, where he earned his fame, his troops lacked either the numbers or the training for an attack. Also, the Iberian peninsula provides some of the best defensive ground in the world, and he was not slow to take advantage of it.

Much of Wellesley's tactics were dictated by politics, supply, or finance: being merely a general in the field, he had to deal with the vagaries of an unstable government at home; the Portuguese government; various Spanish Juntas, guerrilleros, and warlords. Also, the problem of supply in the barren peninsula was a dire one: the French did not bother to deal with it, and simply looted whatever supplies they needed; Wellesley, needing the goodwill of the populace, was required to bring in his supplies from elsewhere (especially wheat from America) and transport them to his troops in the field. This supply line was his ever-present Achilles' heel, and often he was forced to either retreat or assume a defensive position when his line of supply was threatened.

In his defensive battles, he showed an understanding of defensive tactics almost unmatched: he, almost alone of Napoleonic commanders, realised the use of a reverse slope in a defensive battle, and made use of them whenever he could, to conceal his numbers and protect his men from artillery. Still, he rarely missed an opportunity to counter-attack, and many French columns found themselves cut up by musket volleys, then attacked with bayonets.

Wellesley could be very aggressive: his river crossing at Oporto was a breathtaking gamble; only the mistake of a subordinate officer allowed any of Soult's army to escape. On the attack also, he showed a clear understanding of tactics and terrain: at the Battle of Vitoria, he led a massive, well-coordinated attack in four columns from three directions, almost destroying the French army, forcing them to abandon all their baggage and supplies and all but one of their 138 guns.

Still, he had to be very cautious: at the Lines of Torres Vedras, when Massena's army was attempting to besiege Lisbon, and being besieged in turn, Wellesley often stood on a parapet, surveying the French army with a telescope, muttering: "I could whip them, but it would take 10,000 men, and as this is the only army England has, it behoves me to take care of it."

Since the total number of French troops in Spain always heavily outnumbered the available number of British and Portuguese troops, it was always possible for the French command to abandon some region, as they did after Salamanca, in order to concentrate a larger army than the British; Wellington was therefore always cautious during his incursions into Spain, with the great exception of the last.

In the campaign leading up to the Battle of Vitoria, he was cut off from his supply line to Lisbon, so he re-established it on the north coast of Spain, throwing the French front-line troops back upon their reserves.

All his sieges were successful, with the exception of the Siege of Burgos, probably his worst defeat. Most of these were in India, against Indian armies of worse training, arms, and morale than the French; he may have been overconfident at Burgos. Wellington had to retake the frontier fortresses (like Almeida) several times, because the French were equally successful in capturing them from the Allied garrisons. Also, he did not have the time for lengthy, Vauban-style sieges, because the French would have been able to gather up relieving forces. Hence, his brief and bloody, though successful, assaults on Ciudad Rodrigo and on Badajoz.

He disliked his cavalry commanders. He wrote a famous letter on 18 July 1812, accusing the cavalry of being unable to manoeuvre except on Wimbledon Common, and of always charging in a body, instead of forming in two lines – one to charge and one as a reserve. Of course, until 1815, he was denied the talents of the brilliant Henry Paget because of the family feud between them.

He acted as his own head of intelligence, and closely supervised both the supplying and the payment of his troops.

Much of his energy was diverted to political aims: shoring up his support in the British and Spanish governments, lobbying for his choice of officers, and cultivating the cooperation of the Portuguese and Spanish populations. While the French army alienated the latter by seizing their food and shooting anyone who resisted them, Wellington imported most of his food from abroad, paid cash for what he needed locally, and exercised strict discipline over his troops, regularly hanging men for looting, rape, murder, or desecration of religious sites. The locals repaid him with obedience, enlistment and information on French movements. In particular, the guerrilleros (partisans) operated in fairly close cooperation with British troops against the French, especially in their attacks on French couriers, and the passing of the captured French dispatches to Wellington.

Legacy and contemporaries

As a general, Wellington is often compared to the 1st Duke of Marlborough, with whom he shared many characteristics, chiefly a transition to politics after a highly successful military career.

In September 1805, the then Major-General Wellesley, newly returned from his victorious campaign in India but not yet particularly well-known to the public, reported to the office of the Secretary for War to request a new assignment. In the waiting room, he met Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, already a legendary figure after his victories at the Nile and Copenhagen, and who was briefly in England after months chasing the French Toulon fleet to the West Indies and back. Nelson began a near-monologue about nothing of importance in a manner Wellesley found "vain and silly", but something the younger man said caused Nelson to guess that he might be a person of importance after all. Nelson slipped from the room to inquire who the young general was, and on his return switched to a very different tone, discussing the war and British policies with insight and imagination. Wellesley had a delightful conversation with him for the next half hour. This was the only time that the two men met; Nelson was killed at his great victory at Trafalgar just seven weeks later.[70]

Arms, titles, honours and styles

Wellington received numerous awards and honours during and after his lifetime. These include a wide range of titles as well as buildings in his name, such as Wellington's Column, and the Wellington Monument in his native Dublin. Two of his former homes are now open to the public, including Apsley House in London and Stratfield Saye House. His name has also been applied to numerous buildings and places, including Wellington, the capital of New Zealand and HMS Iron Duke, a First World War battleship. In addition he is the only person to have had the honour of having not one but two RAF bombers named for him - the Vickers Wellesley and the Vickers Wellington, and at a time when the convention was for British bombers to be named after landlocked cities.

A number of monuments have been erected to Wellington's name around Great Britain and Ireland:

- Wellington Arch on Hyde Park Corner, London

- Wellington College, Berkshire, in Crowthorne, Berkshire, the UK national monument to Wellington

- Wellington Monument, Dublin

- Wellington Monument, Somerset in the Blackdown Hills, near Wellington in Somerset

- Wellington Monument, Woodhall Spa, Lincolnshire

- Wellington Statue, Aldershot

- Wellington's Column in Liverpool

- a monument in his birthplace in Trim, County Meath, Ireland

Wellington's tomb is in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral, near that of Sir Christopher Wren. The casket is decorated with banners which were made for his funeral procession. Originally, there was one for Prussia, which was removed during World War I and never reinstated.[71]

From 1971 until 1990, the Duke of Wellington's picture featured on the reverse of Series D £5 banknotes issued by the Bank of England, along with a scene from the Battle of Waterloo.[72]

Nicknames

Apart from giving his name to "Wellington boots", the Duke of Wellington also had several nicknames.

- The "Iron Duke", possibly after an incident in 1830 in which he installed metal shutters to prevent rioters breaking windows at Apsley House

- Officers under his command called him "The Beau", as he was a fine dresser, or "The Peer" after he was made a Viscount.

- Regular soldiers under his command called him "Old Nosey" or "Old Hookey", on account of his prominent, aquiline nose.

- Spanish and Portuguese troops called him "the Eagle" and "Douro" respectively.

- "The Beef", a reference to the famous Beef Wellington dish. It is also his nickname in the popular board game, Risk(?)

References

- ↑ Longford E., Wellington: The Years of The Sword Harper and Row Publishers, 1969; p.7

- ↑ Journal of the Kildare Archaeological Society, Vol. X, No. 1, p. 90–94.

- ↑ Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 60; p. 170

- ↑ Guedalla, The Duke, p.480

- ↑ Arthur Wellesley was baptised in 1769. His baptismal font was donated to St. Nahi's Church in Dundrum, Dublin, in 1914.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 7.

- ↑ Quoted, for instance, in Neillands, Robin, Wellington and Napoleon: Clash of Arms, Barnes & Noble Books, 2002, p. 32.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 6–7.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Holmes, p. 8.

- ↑ Longford E., op.cit., 1969; p.54. Wellington's first signature as Arthur Wellesley was on a letter date 19 May 1798.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Holmes, p. 9.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 19–20.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Holmes, p. 20.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Holmes, p. 21.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Holmes, p. 22.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 23.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Holmes, p. 24.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Holmes, p. 25.

- ↑ Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, 10 Downing Street, Accessed 16-06-08.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 26.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 27.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Holmes, p. 28.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Holmes, p. 30.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 31.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Holmes, p. 32.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Holmes, p. 33.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 34.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 40.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Holmes, p. 41.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 42.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Holmes, p. 49.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 44.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 47.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 51.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Holmes, p. 53.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 Holmes, p. 56 - 58.

- ↑ The Battle of Seringapatam: Chronology, Macquarie University, Accessed 17-06-08.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Holmes, p. 59 - 60.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 62.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 63.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 64–65.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 65.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 67.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Holmes, p. 69.

- ↑ Wellesley had actually been gazetted Major-General on the 29 April, but the news took several months to reach him by sea.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Holmes, p. 73.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 74.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 48.5 48.6 48.7 48.8 48.9 Holmes, p. 75 - 81.

- ↑ Longford, p. 93 .

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Holmes, p. 82.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 83.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 Holmes, p. 85 - 87.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Holmes, p. 84.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 85.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 96.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 102–103.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 124.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 142.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 162.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 168.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 189.

- ↑ Wellington to Bathurst, dispatches, p. 496.

- ↑ Napoleon and His Marshals. London: PRION, 1996 (originally Macmillan and Co., 1934), p. 185.

- ↑ Barbero, Alessandro. The Battle : A New History Of Waterloo. St Martins Pr. pp. 2. ISBN 0-8027-1453-6.

- ↑ The Duke of Wellington and King's College London, King's College London, Accessed 08-06-08.

- ↑ "The Duel: Wellington versus Winchilsea". King's College London (2004). Retrieved on 2008-09-04.

- ↑ Holmes, p. 275.

- ↑ "Web of English History".

- ↑ Glover, p. 334.

- ↑ Professor Richard Holmes Wellington - the Iron Duke

- ↑ "Wellington's Tomb". St Paul's Cathedral. Retrieved on 2008-10-20.

- ↑ "Withdrawn banknotes reference guide". Bank of England. Retrieved on 2008-10-17.

Sources

- Beatson, Alexander. A collection of the Duke’s letters. A View of the Origin and Conduct of the War with Tippoo Sultaun. London: Bulmer and Co., 1800.

- Brett-James, ed. Wellington at War 1794–1815, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1961.

- Glover, Michael, The Peninsular War 1807 – 1814. London: Penguin Books, 2001 ISBN 0-141-39041-7 (first published 1974).

- Guedalla, Phillip, The Duke. London, Hodder and Stoughton, 1931.

- Hilbert, Charles. Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, time and conflicts in India on behalf of the British East India Company and the British crown. Military Heritage, August 2005, Volume 7, No. 1, pp.34 to 41), ISSN 1524-8666.

- Holmes, Richard. Wellington: The Iron Duke. London: Harper Collins Publishers, 2002 ISBN 0-00-713750-8.

- Hutchinson, Lester. European Freebooters in Mogul India. New York: Asia Publishing House, 1964.

- Longford, Elizabeth. Wellington: The Years of The Sword. New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1969.

- Mill, James. The History of British India. 6 vols. 5th ed. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1968.

- Murray, John. The dispatches of Field Marshall the Duke of Wellington : during his various campaigns in India, Denmark, Portugal, Spain, the Low Countries, and France, from 1799 to 1818. Volume X. London: 1838. Retrieved on 14 November 2007.

External links

- ThePeerage.com

- Duke of Wellington Chronology World History Database

- Wellington's Military and Political Career

- Duke of Wellington's Regiment - West Riding

- Works by Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington at Project Gutenberg

- Images of political cartoons featuring the Duke of Wellington

- Duke of Wellington At Find A Grave

- More about Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington on the Downing Street website

- A Paper about the Duke of Wellington

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William Elliot |

Chief Secretary for Ireland 1807 – 1809 |

Succeeded by Robert Dundas |

| Preceded by The Earl of Mulgrave |

Master-General of the Ordnance 1819 – 1827 |

Succeeded by The Marquess of Anglesey |

| Preceded by The Viscount Goderich |

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom 22 January 1828 – 16 November 1830 |

Succeeded by The Earl Grey |

| Leader of the House of Lords 1828 – 1830 |

||

| Preceded by The Viscount Melbourne |

Prime Minister (pro tempore) 17 November 1834 – 9 December 1834 |

Succeeded by Sir Robert Peel |

| Preceded by Viscount Duncannon |

Home Secretary (pro tempore) 1834 |

Succeeded by Henry Goulburn |

| Preceded by Thomas Spring Rice |

Secretary of State for War and the Colonies (pro tempore) 1834 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Aberdeen |

| Preceded by The Viscount Palmerston |

Foreign Secretary 1834 – 1835 |

Succeeded by The Viscount Palmerston |

| Preceded by The Viscount Melbourne |

Leader of the House of Lords 1834 – 1835 |

Succeeded by The Viscount Melbourne |

| Leader of the House of Lords 1841 – 1846 |

Succeeded by The Marquess of Lansdowne |

|

| Parliament of Ireland | ||

| Preceded by Hon. William Wellesley-Pole |

Member of Parliament for Trim 1790 – 1797 |

Succeeded by Clotworthy Taylor |

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

| Preceded by Thomas Davis Lamb Sir Charles Talbot |

Member of Parliament for Rye with Sir Charles Talbot 1806 |

Succeeded by Patrick Crauford Bruce Michael Angelo Taylor |

| Preceded by Samuel Boddington |

Member of Parliament for Tralee May 1807 – July 1807 |

Succeeded by Evan Foulkes |

| Preceded by Sir Christopher Hawkins Frederick William Trench |

Member of Parliament for Mitchell with Henry Conyngham Montgomery 1807 |

Succeeded by Edward Leveson-Gower George Galway Mills |

| Preceded by Isaac Corry Sir John Doyle |

Member of Parliament for Newport with The Viscount Palmerston 1807 – 1809 |

Succeeded by The Viscount Palmerston Sir Leonard Thomas Worsley-Holmes |

| Party political offices | ||

| First None recognised before

|

Leader of the British Conservative Party 1828 – 1834 |

Succeeded by Sir Robert Peel, Bt |

| Conservative Leader in the Lords 1828 – 1846 |

Succeeded by The Lord Stanley |

|

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Vacant

Title last held by

The Lord Whitworth of Newport Pratt |

British Ambassador to France 1814 – 1815 |

Succeeded by Sir Charles Stuart |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by Baron Grenville |

Chancellor of the University of Oxford 1834 – 1852 |

Succeeded by Earl of Derby |

| Military offices | ||

| Preceded by The Duke of Richmond |

Governor of Plymouth 1819 – 1827 |

Succeeded by The Earl Harcourt |

| Preceded by HRH The Duke of York |

Commander-in-Chief of the Forces 1827 – 1828 |

Succeeded by The Lord Hill |

| Preceded by The Viscount Hill |

Commander-in-Chief of the Forces 1842 – 1852 |

Succeeded by The Viscount Hardinge |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by The Earl of Malmesbury |

Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire 1820 – 1852 |

Succeeded by The Marquess of Winchester |

| Preceded by The Marquess of Hastings |

Constable of the Tower Lord Lieutenant of the Tower Hamlets 1827 – 1852 |

Succeeded by The Viscount Combermere |

| Preceded by The Earl of Liverpool |

Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports 1829 – 1852 |

Succeeded by The Marquess of Dalhousie |

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New creation | Duke of Wellington 1814 – 1852 |

Succeeded by Arthur Richard Wellesley |

| Dutch nobility | ||

| Preceded by New Creation |

Prins van Waterloo 1815–1852 |

Succeeded by Arthur Richard Wellesley |

| Spanish nobility | ||

| Preceded by New Creation |

Duque de Ciudad Rodrigo 1812–1852 |

Succeeded by Arthur Richard Wellesley |

| Portuguese nobility | ||

| Preceded by New Creation |

Duque da Vitória 1812–1852 |

Succeeded by Arthur Richard Wellesley |

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Wellesley, Arthur, 1st Duke of Wellington |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Wesley, Arthur (birth name);Viscount Wellington; Earl of Wellington; Marquess of Wellington |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Soldier and statesman |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1 May 1769 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Dublin, Ireland |

| DATE OF DEATH | 14 September 1852 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Walmer Castle |