Apocalypse

Apocalypse (Greek: Ἀποκάλυψις Apokálypsis; "lifting of the veil") is a term applied to the disclosure to certain privileged persons of something hidden from the majority of humankind. Today the term is often used to refer to the end of the world, which may be a shortening of the phrase apokalupsis eschaton which literally means "revelation at the end of the æon, or age".

Origins

Apocalypse technically refers to a revelation of God's Will. Thus, in Revelation, we see a clear pattern of future events: the various periods of the church, shown through the letters to the seven churches; the throne of God in Heaven and His Glory; the judgments that will occur on the earth; the final form of gentile power; God' re-dealing with the nation Israel[1] based upon covenants mentioned in the Old Testament; the second coming proper; the one-thousand year reign of Messiah; the last test of Mankind's sinful nature under ideal conditions by the loosing of Satan, with the judgment of fire coming down from Heaven that follows; the Great White Throne Judgment, and the destruction of the current heavens and the earth, to be recreated as a "New Heaven and New Earth"[2],[3][4] ushering in the beginning of Eternity.

Terminology

Apocalypse, in the terminology of early Jewish and Christian literature, is a revelation of hidden things revealed by God to a chosen prophet or apostle. The term is often used to describe the written account of such a revelation. Apocalyptic literature is of considerable importance in the history of the Judeo-Christian-Islamic beliefs and traditions, because it makes specific references to beliefs such as the resurrection of the dead, judgment day, eternal life, final judgment and perdition. Apocalyptic beliefs predate Christianity, appear throughout other religions, and have been assimilated into contemporary secular society, especially through popular culture (see Apocalypticism). Apocalyptic beliefs also occur in other religious systems, for example, the Hindu concept of pralay. Plus, one of these days, the humans must realize their mistakes.

Changes in meaning from the Second Century A.D. to the present time

From the Second Century A.D. onward, the term "Apocalypse" was applied to a number of books, yet in the process the meaning has vastly changed from the unveiling of new or unseen ideas in ancient Greek to today's meaning of the destruction of earth as we now know it, both Jewish and Christian, which show the same characteristic features. Besides the Apocalypse of John (now generally called the Book of Revelation) included in the New Testament, the Muratorian fragment, Clement of Alexandria, and others mention an Apocalypse of Peter. Apocalypses of Adam and Abraham (Epiphanius) and of Elias (Jerome) are also mentioned; see, for example, the six titles of this kind in the "List of the 60 Canonical Books";[5] and also Development of the New Testament canon.

The use of the Greek noun to designate writings belonging to a certain literary genre is of Christian origin, the original norm of the class being the New Testament Book of Revelation. In 1832 Gottfried Christiane explored the word "Apocalypse" as a description of the book of Revelation,

Characteristic features

Apocalyptic religious writings are regarded as a distinct branch of literature. This genre has several characteristic features.

Dreams or Visions

It is unknown whether dreams or visions of the Apocalypse have been reported. Thus, it is unknown if the Apocalypse will happen.

Angels

The introduction of Angels as the bearers of the revelation is a standing feature. At least two angel-classes are mentioned in biblical scripture: the Cherubim[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13] and the Seraphim.[14] God may give instructions through the medium of these heavenly messengers, and who act as the seer's guide. God may also personally give a revelation, as is shown in the Book of Revelation through the person of Jesus Christ.

There is hardly an example of a true Apocalypse in which the instrumentality of angels in giving the message is not made prominent. In the Assumption of Moses, which consists mainly of a detailed prediction of the course of Israelite and Jewish history, the announcement is given to Joshua by Moses, just before the death of the latter. So, too, in the Sibylline Oracles, which are for the most part a foretelling of future events, the Sibyl is the only speaker. Neither of these books are truly representative of apocalyptic literature in the narrower sense (see below).

"Beast" - Endtime Ruler; also known as Antichrist

In the Old and New Testaments, a particular individual is singled out as the particular focus of God's wrath. This individual is known in biblical scripture by many titles such as the "beast", the "little horn",[15][16] the "prince that will come" and other titles. One ancient prince was singled out in scripture, the Prince of Tyrus, who may be considered a 'type' of antichrist.[17]

After the judgment of the Prince of Tyrus, God directs the prophet Ezekiel to write a judgment about the King of Tyrus, and from the scripture is learned that this individual is not a human being, but "the anointed cherub that covereth".[18] From further reading of the text it is learned that the cherub being addressed here is Satan, as this was his former position before the throne of God before his fall. Satan is also viewed as a 'prince'[19][20][21] that will eventually be judged.

Future

Apocalyptic visions through the writing of these scriptures is how the prophets revealed God's justice as taking place in the future. This genre has a distinctly religious aim, intended to show God's way of dealing with humankind, and God's ultimate purposes. The writers present, sometimes very vividly, a picture of coming events, especially those connected with the end of the present age. In certain of these writings the subject-matter is vaguely described as "that which shall come to pass in the latter days" (Daniel 2:28;[22] compare verse 29); similarly Daniel 10:14, "to make thee understand what shall befall thy people in the latter days";[23] compare Enoch, i.1, 2; x.2ff. So, too, in Revelation 1:1 (compare the Septuagint translation of Daniel 2:28ff), "Revelation ... that which must shortly come to pass."

Past history is often included in the vision, usually in order to give the proper historical setting to the prediction, as the panorama of successive events passes over imperceptibly from the known to the unknown. Thus, in the eleventh chapter of Daniel, the detailed history of the Greek empire in the East, from the conquest of Alexander down to the latter part of the reign of Antiochus Epiphanes (verses 3-39, all presented in the form of a prediction), is continued, without any break, in a scarcely less vivid description (verses 40-45) of events which had not yet taken place, but were only expected by the writer: the wars which should result in the death of Antiochus and the fall of his kingdom. All this, however, serves only as the introduction to the remarkable eschatological predictions in the twelfth chapter, in which the main purpose of the book is to be found.

Similarly, in the dream recounted in 2 Esdras 11 and 12, the eagle, representing the Roman Empire, is followed by the lion, which is the promised Messiah, who is to deliver the chosen people and establish an everlasting kingdom. The transition from history to prediction is seen in xii.28, where the expected end of Domitian's reign – and with it the end of the world – is foretold. Still another example of the same kind is Sibyllines, iii.608-623. Compare also Assumptio Mosis, vii-ix. In nearly all the writings which are properly classed as apocalyptic the eschatological element is prominent. The growth of speculation regarding the age to come and the hope for the chosen people more than anything else occasioned the rise and influenced the development of apocalyptic literature.

Imagery

The element of the mysterious, apparent in both the subject and the manner of the writing, is a marked feature in every typical Apocalypse. The literature of visions and dreams has its own traditions which are well illustrated in Jewish (or Jewish-Christian) apocalyptic writing.

This apocalyptic quality appears most plainly in the use of fantastic imagery. The best illustration is furnished by the strange living creatures which figure in so many of the visions – "beasts" or "living creatures", as is written in Revelation 4[24] in which the properties of men, mammals, birds, reptiles, or purely imaginary beings are combined in a way that is startling and often grotesque. This characteristic feature is illustrated in the following list of the most noteworthy passages in which such creatures are introduced: Daniel 7:1-8, 8:3-12 (both passages of the greatest importance for the history of apocalyptic literature); Enoch, lxxxv.-xc.; 2 Esdras 11:1-12:3, 11-32; Greek Apoc. of Bar. ii, iii; Hebrew Testament, Naphtali's, iii.; Revelation 6:6ff (compare Apocalypse of Baruch [Syr.] li.11), ix.7-10, 17-19, xiii.1-18, xvii.3, 12; the Shepherd of Hermas, "Vision," iv.1. Certain mythical or semi-mythical beings which appear in the Hebrew Bible also play an important role in these books. Thus "Leviathan", mentioned in the Old Testament[25][26][27][28] and "Behemoth", mentioned also in the Old Testament,[29] as well as (Enoch, lx.7, 8; 2 Esdras 6:49-52; Apocalypse of Baruch xxix.4); "Gog and Magog" (Sibyllines, iii.319ff, 512ff; compare Enoch, lvi.5ff; Revelation 20:8). Foreign mythologies are also occasionally laid under contribution (see below).

Mystical symbolism

Mystical symbolism is another frequent characteristic of apocalyptic writing. This feature is illustrated in the instances where gematria is employed either for the sake of obscuring the writer's meaning, or enhancing its meaning further as a number of ancient cultures used letters also as numbers (i.e., the Romans with their use of 'roman numerals'). Thus, the mysterious name "Taxo," "Assumptio Mosis", ix. 1; the "number of the beast" 666, of Revelation 13:18;[30] the number 888 ('Iησōῦς), Sibyllines, i.326-330.

Similar to this discussion is the frequent prophecy of the length of time through which the events predicted must be fulfilled. Thus, the "time, times, and a half," Daniel 12:7[31] which has generally been agreed to be 3½ years in length by dispensationalists; the "fifty-eight times" of Enoch, xc.5, "Assumptio Mosis", x.11; the announcement of a certain number of "weeks" or days, which starting point in Daniel 9:24, 25 is the "the going forth of the commandment to restore and to build Jerusalem unto the Messiah the Prince shall be seven weeks",[32] ff, a mention of 1290 days after the covenant/sacrifice is broken (Daniel 12:11),[33] 12; Enoch xciii.3-10; 2 Esdras 14:11, 12; Apocalypse of Baruch xxvi-xxviii; Revelation 11:3, which mentions "two witnesses" with supernatural power,[34] 12:6;[35] compare Assumptio Mosis, vii.1. Symbolic language is also used to describe persons, things, or events; thus, the "horns" of Daniel 7 and 8;[36] Revelation 17[37] and following; the "heads" and "wings" of 2 Esdras xi and following; the seven seals of Revelation 6;[38] trumpets, Revelation 8;[39] "vials of the wrath of God" or "bowl..." judgments, Revelation 16;[40] the dragon, Revelation 12:3-17,[41] Revelation 20:1-3;[42] the eagle, Assumptio Mosis, x.8; and so on.

As examples of more elaborate prophecies and allegories, aside from those in Daniel Chapters 7 and 8; and 2 Esdras Chapters 11 and 12, already referred to, may be mentioned: the vision of the bulls and the sheep, Enoch, lxxxv and following; the forest, the vine, the fountain, and the cedar, Apocalypse of Baruch xxxvi and following; the bright and the black waters, ibid. liii and following; the willow and its branches, Hermas, "Similitudines," viii.

End of the age

In John's apocalypse, the book of Revelation, he refers to the "unveiling" or "revelation" of Jesus Christ as Messiah. This term has been downgraded in common usage to refer to the end of the world. But it is more accurate to interpret the term "end of the world", as we see in the King James Version of the Bible, as the "end of the age". The word translated as "world" is actually the Greek word "eon" or "age".

The simple pictures of the end of the age as books of the Old Testament were images of the judgment of the wicked, as well as the resurrection and glorification of those who were given righteousness before God. The dead are seen in the book of Job and in some of the Psalms as being in Sheol, awaiting the final judgment. The wicked will then be consigned to eternal torment in the fires of Gehinnom, or the Lake of Fire mentioned in Revelation[43][44][45].[46][47]

The New Testament letters written by the Apostle Paul expand on this theme of the judgment of the wicked, and the glorification of those who belong to Christ or Messiah. In his letters to the Corinthians and the Thessalonians Paul expounds further on the destiny of the righteous. He speaks of the simultaneous resurrection and rapture of those who are in Christ, (or Messiah). This is a combined apocalyptic event that comes at the end of this age and before the coming Millennium.

Christianity had a Millennial expectation for glorification of the righteous from the time it emerged from Judaism and spread out into the world in the first century. The poetic and prophetic literature of the Hebrew Bible, particularly in Isaiah, were rich in Millennial imagery. The New Testament Congregation after Pentecost carried on with this theme. During his imprisonment by the Romans on the Island of Patmos, John described the visions he experienced, writing the Book of Revelation. Revelation chapter 20 contains several reference to a thousand year reign of Christ/Messiah upon this earth.

Throughout Church history, the kings and princes of Europe had traditionally viewed with extreme disfavor the idea of a judgment at the end of this age and a Millennium to follow. King Henry VIII was very angry when he heard that his subjects were reading smuggled copies of William Tyndale's New Testament. Upon hearing that they were discussing the judgment at the end of the age, he flew into a rage. Archbishop Wolsey was summoned and questioned about this matter. A series of events then led to William Tyndale being hunted down, captured, condemned, and burned at the stake.

Preaching or teaching on end time apocalytic themes in the "Three Self" government church in China is strictly forbidden.

Modern Christian movements in the 18th and 19th Centuries were characterized by a rise of Millennialism. Christian Apocalyptic eschatology was a continuation of the same two themes referred to throughout all of scripture as "this age" and "the age to come". Evangelicals have been in the forefront in rediscovering and popularizing the biblical prophecy of a major confrontation between good and evil at the end of this age, a coming Millennium to follow, and a final confrontation whereby the wicked are judged, the righteous are rewarded and the beginning of Eternity is viewed.

Most evangelicals have been taught a form of Millennialism known as Dispensationalism, which arose in the 19th century. Dispensationalism sees separate destinies for the Church and Israel. Its concept of a special Pre Tribulation Rapture of the Church has become extremely popular. This is the central thesis of the Left Behind books and films. Recently, however, Dispensationalism has been undergoing some opposition from those who teach and embrace what is termed Traditional Millennialism. Prominent among them are those who hold to a Post Tribulation Rapture.

One of the most complete exegetical works on the meaning of the Book of Revelation was written by Emanuel Swedenborg called the Apocalypse Revealed, first published in two volumes in Amsterdam in 1766. A more current book, utilizing the literal method of interpretation, is "The Revelation Record" by Henry M. Morris.[48]

See also

- Antichrist

- Apocalypse of Abraham

- Apocalypse of Peter

- Apocalyptic literature

- Apocalypticism

- Armageddon

- The Beast (Bible)

- Bible prophecy

- Dajjal, Muslim anti-christ figure

- Doomsday

- Dream dictionary

- Eschatology

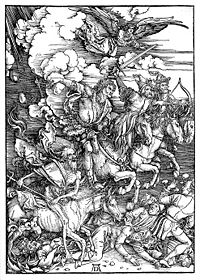

- Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

- Gnostic Apocalypse of Peter

- Kali Yug, Hindu view

- Kalki, Hindu prophetic figure

- Millennialism

- Millenarianism

- New World Order (conspiracy)

- Omnicide

- Premillennialism

- Qiyamah, Muslim view

- Ragnarök

- Summary of Christian eschatological differences

Film/Television

- Apocalypse Now, a film directed by Francis Ford Coppola

- Children of Men, directed by Alfonso Cuarón

- Revelations, an NBC miniseries chronicling the end of days.

- Metalocalypse, an animation based around a metal band that within the show many government officials and leaders of the Catholic Church believe will trigger the 'Metalocalypse'.

- In The Simpsons episode "Simpsons Bible Stories", the Simpsons fall asleep in church and wake up to find Springfield awash in the flames and destruction of the Apocalypse. When God raises Lisa up to Heaven, Homer pulls her back down so she can go to Hell with the rest of the family.

- "Apocalypse" is the title of Smallville's 150th episode, directed by Tom Welling.

- The Lone Biker of the Apocalypse in Raising Arizona

- Resident Evil:ApocalypseA movie of the Resident Evil series(part 2).

- SupernaturalA TV Series will be focused on the apocalypse in season 4

Literature, etc.

- Revelation: St. John the Divine Prophecies for the Apocalypse and Beyond, by Peter Lorie (c)1995; published by Boxtree; ISBN 1852839821.

- Lectures on the Apocalypse: Or, Book of Revelation of St. John the Divine by Frederick Denison Maurice M.A..

- The Meaning of Millennium - Apocalyptic Visions and Revisions: Texts and Contexts; by Damian Thompson, from The End of Time; published by the Norton Anthology of English Literature - Norton Topics Online.

- Apocalypse Nerd, a comic book exploring human relationships in the Apocalypse.

- The End Is Nigh, a magazine looking at the end of the world

- English Apocalypse Manuscripts.

- Just a Couple of Days, an apocalyptic novel with a happy ending.

- Good Omens by Neil Gaiman & Terry Pratchett - a fantasy/comedy novel detailing the Apocalypse and Armageddon

- BLASSREITER

- X/1999

- Albert and the American Revelation, by Daniel Oldis (c)1986; published by Libra Publishers; ISBN 9780872121966; end-of-times satire.

Escape The Fate Have also made a song called "My Apocalypse" [[*"The Stand" by Stephen King]]

Music

- Absolution, an album by Muse regarding Apocalypse.

- A song, on the above album, is titled 'Apocalypse Please'.

- Save The World Burn It Down (song) by the band Babalon about personal apocalypse.

- "Supper's Ready", a 23-minute epic by progressive rock band Genesis, found on their 1972 album "Foxtrot", deals with a couple who falls in love and experience the Apocalypse.

- F♯A♯∞, an album by Canadian post-rock band Godspeed You! Black Emperor, which deals with thoughts of a coming apocalypse.

- The World's Famous Ending a song by Graffitee, anthe extremely personal song regarding the personal apocolpyse to himself and also based on his movie currently in production.

- The British neofolk band Current 93 has released concept albums about the apocalypse, defining the term apocalyptic folk.

- Shadowboxing the Apocalypse is a prominent line in the Grateful Dead song "My Brother Esau" from the 1987 album, In The Dark.

- Apocalypse: A Song By Emarosa

- Apocalypse: A Song By AGraceful

- My Apocalypse: A Song By Escape The Fate

- This Or The Apocalypse: A technical metalcore band from Lancaster, PA.

- Day of the Apocalypse; A song by Arkangel

- Apocalypse: Indie /pop/mod/etc band from South London originally on Jamming Records then EMI. Album Release on Cherry Red Records still available. Paul Weller produced 'Teddy' and Release'. The band toured with The Jam and supported them at the Jam's last ever gig at Brighton. Band members were Kevin Bagnell, Chris Boyle, Jeff Carrigan, Tony Fletcher and Tony Page.

- My Apocalypse: A song by Metallica

- Pale Horse Apocalypse: A song Dy DevilDriver

Radio

- Apocalypse, a radio drama adaptation of the short story "Finis" by Frank L. Pollack, which describes a near-future end-of-the-world scenario involving a new star.

Book References (arranged alphabetically by author)

Angels

- "Angels: God's Secret Agents" by Billy Graham (Revised & Expanded) ©1975, 1986; Word Books Publisher, Waco, Texas.

Antichrist - Speculations and Theories

- "How to Recognize the Antichrist" by Arthur E. Bloomfield ©"1975; Bethany Fellowship

- "Gorbachev: Has the Real Antichrist Come?" by Robert W. Faid ©1988: Victory House Publishers.

- "The Man The False Prophet and The Harlot", subtitled "The Name of the Antichrist Finally Revealed" by Dr. Anthony M. Giliberti ©1991; Published by "This Is The Generation" Library of Congress Catalog Number 90-93451 ISBN 0-9628419-0-0.

- "Global Peace and the Rise of Antichrist" by Dave Hunt ©1990; Harvest House Publishers Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publishing Data; ISBN 0-89081-831-2.

Armageddon

- "Till Armageddon", subtitled "A Perspective on Suffering" by Billy Graham ©1981; Word Books Publishers.

- "Armageddon, Oil and the Middle East Crisis" Revised, by John F. Walvoord ©1974, 1976, 1990; Zondervan Publishing House, 1415 Lake Drive, S.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49506; ISBN 0-310-53921-8

Biblical Numbers, Code Theories and Computer Associations

- "Number in Scripture" by E. W. Bullinger, D.D.; ©1967; Kregel Publications, Grand Rapids, Michigan 49501 Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 67-26498; ISBN 0-8254-2204-3

- “The Bible Code” by Michael Drosnin; ©1997; Published by Simon & Schuster, 1230 Ave. of the Americas, New York, NY 10020. ISBN 0-684-81079-4.

- “Bible Code II: The Countdown” by Michael Drosnin; ©2002 One Honest Man, Inc. Published by Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0R1, England.

- "City of Revelation" subtitled "A Book of Forgotten Wisdom" by John Michell ©1972; Ballantine Books (first printing: 11/73 Library of Congress Cat. No. 72-88116 SBN 345-23607-6-150. (NOTE: there may be only one copy of this book. Review copy sticker is inside. Contains information on Gematria, a mathematical science. This is NOT the John Michell you will find on Wikipedia!)

- "Computers and The Beast of Revelation" by David Webber & Noah Hutchings ©1986; Huntington House Publishers.

Catholicism and its influence

- "A Woman Rides the Beast" (subtitled, "The Catholic Church in the Last Days" by Dave Hunt; ©1994; Harvest House Publishers.

- "The Cult of the Virgin", subtitled "Catholic Mariology and the Apparitions of Mary" by Elliott Miller and Kenneth R. Samples; forward by Normal L. Geisler; © 1992; published by Baker Book House, Grand Rapids, Michigan 49516; ISBN 0-8010-6291-8.

- "Once a Catholic", subtitled "What You Need to Know about Roman Catholicism" by Tony Coffey; ©1993; Harvest House Publishers, Eugene, Oregon 97402. ISBN 1-56507-045-3.

The Church, Israel, Islam, and relation to Biblical Prophecy

- "A History of Israel" (2nd Edition) by John Bright ©1972; The Westminster Press. (NOTE: This is NOT the John Bright you will find on Wikipedia!)

- "A New Testament History; the story of the Emerging Church" by Floyd V. Filson. ©MCMLXIV; W. L. Jenkins Published by The Westminster Press Library of Congress Catalog No. 64-15360.

- "The Fall Feasts of Israel" by Mitch and Zhava Glaser; ©1987; The Moody Bible Institute of Chicago; ISBN 0-8024-2539-9; Library of Congress.

- "A Cup of Trembling" by Dave Hunt ©1995; Harvest House Publishers, Eugene, Oregon 97402; ISBN 1-56507-334-7

'Daniel' and 'Revelation' Compared

- "Daniel and Revelation" subtitled "A Study of Two Extraordinary Visions" by James M. Efird ©1978; Judson Press, Valley Forge, PA 19481 ISBN 0-8170-0797-0

- "Daniel's Prophecy of the 70 Weeks" by Alva J. McClain 1940, ©1969; Academie Books/Zondervan House.

NOTE: Also see 'Things to Come' listed below.

Date-Setting Books

- "1994?" by Harold Camping; ©1992; Published by Vantage Press, Inc., 516 West 34th Street, NY, NY 10001. ISBN 0-533-10368-1; Library of Congress Cat. No. Unknown.

- "Shock Wave 2000!" subtitled "The Harold Camping 1994 Debacle"; by Robert Sungenis, Scott Temple, and David Allen Lewis; ©1994 New Leaf Press, Inc., P.O. Box 311, Green Forest AR 72638; ISBN 0-89221-269-1; Library of Congress: 94-67493 NOTE: This book is a refutation to Harold Camping's book listed above. This author exposes most of Harold Camping's misconceptions, etc. Harold Camping is currently the Station Manager on his radio station WFME A.M. His 'school of thought' is Amillennial. But it is worth viewing an article on the remarkable irony in Sungenis' criticism of Camping, here.

Discussions of 'Genesis', the 'Days of Noah', and Relation to Prophecy

- "The Genesis Record" by Henry M. Morris ©1976; Baker Book House and Master Books (NOTE: This book is a companion book to "The Revelation Record")

- "Many Infallible Proofs" by Henry M. Morris ©1974; Creation Life Publishers.

- "Scientific Creationism" by Henry M. Morris (General Edition) ©1974; Creation-Life Publishers (Master Books)

- "The Genesis Flood" by John C. Whitcomb and Henry M. Morris ©1961; The Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co. ISBN 0-087552-338-2 Library of Congress Cat. No. 60-13463.

Dispensational Thought

- "Hidden Prophecies in the Psalms" by J.R. Church; ©1986; Prophecy Publications, Oklahoma City, OK 73153; ISBN 0-941241-00-9

- "Not Wrath but Rapture!" by Harry A. Ironside; NO DATE; published by Loizeaux Brothers, Inc.

- "The Truth About Armageddon" by William Sanford Lasor ©1982; Harper & Row Publishers.

- "The Late Great Planet Earth" by Hal Lindsey with C.C. Carlson ©1970; Zondervan House.

- "Satan is Alive and Well on Planet Earth" by Hal Lindsey with C.C. Carlson ©1972; Zondervan House.

- "A Survey of Bible Prophecy" by R. Ludwigson ©1951; (1973, 1975; The Zondervan Corporation).

- "The Revelation Record" by Henry M. Morris ©1985; Tyndale House Inc. and Creation Life Publishers.

- "Things to Come" by J. Dwight Pentecost ©1958; Zondervan Publishing House, Grand Rapids, Michigan 49506

- "The Secret Book of Revelation" (subtitled: "The Last Book of the Bible") ©1979; by Gilles Quispel; Collins St. James Place, Comdon, 1979.

- "The Rapture Question" by John F. Walvoord (Revised & Enlarged) ©1974; The Zondervan Corporation.

New Age Movement and relation to prophecy

- "The Hidden Dangers of the Rainbow" by Constance Cumbey; ©1983; Huntington House Inc.

- "A Planned Deception: The Staging of A New Age 'Messiah'" by Constance Cumbey; ©1985; Pointe Publishers, Inc.

- "Deceived by the Light" by Doug R. Groothuis; ©1995 Harvest House Publishers, Eugene, Oregon 97402; ISBN 1-56507-301-0

- "Peace, Prosperity, and the Coming Holocaust" subtitled "The New Age Movement in Prophecy", by Dave Hunt; ©1983; Harvest House Publishers.

References

- ↑ "Isaiah 66:22 (King James Version)". BibleGateway. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Isaiah 65:17 (King James Version)". BibleGateway. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "2 Peter 3:13 (King James Version)". BibleGateway. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Revelation 21:1 (King James Version)". BibleGateway. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "The Development of the Canon of the New Testament". NTCanon.org. Retrieved on 2007-11-15."Council of Laodicea (about A.D. 363)". Bible Researcher.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Genesis 3:24 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "2 Kings 19:15 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Psalm 80:1 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Psalm 99:1 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Isaiah 37:16 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Ezekiel 10 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Ezekiel 11:22 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Hebrews 9:1-6 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Isaiah 6:1-7 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Daniel 7:1-28 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Daniel 8:1-27 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Ezekiel 28:2-10 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Ezekiel 28:11-19 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "John 14:30 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "John 16:7-12 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Ephesians 2:2 (King James Version))". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Daniel 2:28 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Daniel 10:14 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Revelation 4 (Darby Translation)". Bible Gateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-12-14.

- ↑ "Job 41:1 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Psalm 74:14 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Psalm 104:26 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Isaiah 27:1 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Job 40:15 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Revelation 13:16-18 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Daniel 12:7 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Daniel 9:24-25 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Daniel 12:11 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Revelation 11:3 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Revelation 12:6 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Daniel 7; Daniel 8 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Revelation 17 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Revelation 6 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Revelation 8 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Revelation 16 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Revelation 12:3-17 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Revelation 20:1-3 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Revelation 19:20 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Revelation 16 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Revelation 20:10 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Revelation 20:14-15 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "Revelation 21:8 (King James Version)". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-21.

- ↑ Henry M. Morris. "The Revelation Record". Tyndale House Inc. and Creation Life Publishers.

External links

- A Brief History of the Apocalypse - Timeline of apocalyptic prognostication

- [1]

- Rapture Ready.com website

.