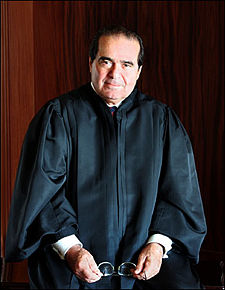

Antonin Scalia

|

Antonin Gregory Scalia

|

|

|

|

|

Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court

|

|

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office September 26 1986 |

|

| Nominated by | Ronald Reagan |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | William H. Rehnquist |

|

|

|

| Born | March 11, 1936 Trenton, New Jersey |

| Spouse | Maureen McCarthy Scalia |

| Alma mater | Georgetown University Harvard Law School |

| Religion | Roman Catholic[1] |

Antonin Gregory Scalia (born March 11, 1936)[2] is an American jurist and the second most senior Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Appointed by Republican President Ronald Reagan, he is considered to be a core member of the conservative wing of the court.

Justice Scalia is a vigorous proponent of textualism in statutory interpretation and originalism in constitutional interpretation, and a passionate critic of the idea of a Living Constitution. He sometimes has a more favorable view of national power and a strong executive than his more ardent states' rights conservative colleague, Clarence Thomas.

Contents |

Early life

Antonin Scalia was born in Trenton, New Jersey. His mother, Kathy Panaro, was born in the United States; his father, S. Eugene, a professor of romance languages, was born in Sicily. He was an only child, as he recalled on 60 Minutes, he did not have any cousins. When Scalia was five years old, his family moved to the Elmhurst section of Queens, New York, during which time his father worked at Brooklyn College in Flatbush, Brooklyn.[3]

Scalia started his education at Public School 13 in Queens. A practicing member of the Roman Catholic Church, Scalia attended Xavier High School, a Catholic and Jesuit school in Manhattan. He graduated first in his class and summa cum laude with an A.B. from Georgetown College at Georgetown University in 1957. While at Georgetown, he also studied at the University of Fribourg, Switzerland and went on to study law at Harvard Law School, where he was a Notes Editor for the Harvard Law Review.[4] He graduated magna cum laude from Harvard Law in 1960, becoming a Sheldon Fellow of Harvard University the following year. The fellowship allowed him to travel throughout Europe during 1960–1961.

On September 10, 1960, Scalia married Maureen McCarthy, an English major at Radcliffe College. Together they have nine children – Ann Forrest (born September 2, 1961), Eugene (labor attorney, former Solicitor of the Department of Labor), John Francis, Catherine Elisabeth, Mary Clare, Paul David (now a priest in the Catholic Diocese of Arlington at St. John's Church in McLean), Matthew (a West Point graduate and U.S. Army Major currently serving as an ROTC instructor at the University of Delaware), Christopher James (currently an English professor at the University of Virginia's College at Wise), and Margaret Jane (studying at the University of Virginia).

Legal career

Scalia began his legal career at Jones, Day, Cockley and Reavis in Cleveland, Ohio, where he worked from 1961 to 1967,[4] before becoming a Professor of Law at the University of Virginia in 1967. In 1971, he entered public service, working as the general counsel for the Office of Telecommunications Policy, under President Richard Nixon, where one of his principal assignments was to formulate federal policy for the growth of cable television. He also suggested policy which would give the White House more influence over the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, ranging from well-chosen appointees to the Board of Directors to giving more power to local stations instead of the national organization.[5] From 1972 to 1974, he was the chairman of the Administrative Conference of the United States, before serving from 1974 to 1977 in the Ford administration as the Assistant Attorney General for the Office of Legal Counsel.[4]

Following Ford's defeat by Jimmy Carter, Scalia returned to academia, taking up residence first at the University of Chicago Law School from 1977 to 1982, and then as Visiting Professor of Law at Georgetown University Law Center and Stanford University. He was chairman of the American Bar Association's Section of Administrative Law, 1981–1982, and its Conference of Section Chairmen, 1982–1983.

In 1982, President Ronald Reagan appointed Scalia to be a Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.[4] Four years later, in 1986, Reagan nominated him to replace William Rehnquist as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States after Rehnquist had been nominated by Reagan to serve as Chief Justice of the United States. Scalia, whose nomination was backed by liberals such as Mario Cuomo, was approved by the Senate in a vote of 98-0[4] (with Barry Goldwater and Jake Garn absent), and he took his seat on September 26, 1986, becoming the first Italian-American Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States. It should be noted that there was very little controversy to his rise to Supreme Court Justice, partly attributed to the elevation of Rehnquist to Chief Justice, who received a lot more coverage.

His law clerks have included prominent figures such as Paul Clement, the Solicitor General under George W. Bush; Lawrence Lessig, a legal activist and professor of law at Stanford University Law School; Joel Kaplan, former Marine Officer and currently the Deputy Chief of Staff for Policy under President George W. Bush; Joseph D. Kearney, Dean and Professor at Marquette University Law School; and Stephen G. Calabresi, professor of law at Northwestern University School of Law and founder of the Federalist Society.

He is a Roman Catholic, and is one of twelve Catholic justices – out of 110 total in the history of the Supreme Court.[6]

Legal philosophy and approach

Statutory and constitutional interpretation

A formalist, Scalia is considered the Court's leading proponent of textualism and originalism (he is careful to distinguish his philosophy of original meaning from original intent). These schools of jurisprudence emphasize careful adherence to the text of both the Constitution of the United States and federal statutes as that text would have been understood to mean when adopted. Scalia will typically use dictionaries contemporaneous with the text's adoption to discern its meaning.

By implication from his originalism, Scalia vigorously opposes the idea of a living constitution, which says that the judiciary has the power to modify the meaning of constitutional provisions to adapt, as expressed in Trop v. Dulles, to "the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society." For Scalia, this idea misunderstands and negates what he calls the "anti-evolutionary purpose" of a constitution. A society that adopts a constitution, he says, "is skeptical...that societies always 'mature,' as opposed to rot."[7] Scalia notes further that many important social advances, such as women's suffrage, were achieved not by judicial fiat but constitutional amendments - whose adoption, Scalia adds, is slow and cumbersome by design. The idea is that amending of the Constitution allows for democratic change as opposed to top-down rule by judges. He also compares his interpretation of the Constitution to general interpretation of other laws or statutes, which are not thought to change over time.[4] When questioned by Harvard Law School Dean Elena Kagan about his support of a "dead Constitution," Scalia replied: "I can package it better than that. I call it the enduring Constitution."[4]

Scalia often relies upon tradition and history to discern the original meaning of unclear constitutional provisions,[8] but when interpreting statutory language, he considers legislative history to be an irrelevant and unreliable interpretive tool: the New York Times wrote Scalia "believes that legislative history is basically fraudulent and that judges should never consider it."[9] This aversion for legislative history is a central tenet of textualism and is infused with both an appreciation for public choice theory[10] and of the realities of legislative compromise (i.e., the statutory text being the only reliable evidence of the deal that was struck).[11] This position often puts him at odds with Justice Breyer, who is perhaps the Court's most steadfast proponent of attempting to discern the overarching legislative objectives of statutes and who values legislative history in that pursuit.

Consistent with his formalist sensibilities, Scalia seeks to maximize the role of the legislature in shaping law and to minimize judicial discretion in its interpretation. For this reason he favors bright-line rules over abstract balancing tests[12] (one of his most frequently-cited works off the bench is an essay titled "The Rule of Law as a Law of Rules,"[13] which also neatly encapsulates Scalia's formalist view of law), and frowns upon judicially-crafted compromises between the requirements of the Constitution and perceived expediency (see, e.g., his dissent in Maryland v. Craig); he has frequently pointed out that, regardless of whether or not moderate views are a good idea in politics, they are at root incompatible with the job of a judge: "[w]hat is a 'moderate interpretation' [of the Constitution])? Halfway between what it says and what you want it to say?"[14]

Scalia's originalism frequently puts him on the conservative side of the Court in constitutional cases, and he is generally perceived as a conservative member of the court. He has received the lowest Segal-Cover score of the current justices, and the lowest of all Supreme Court nominees measured; whereby the lower the score the more conservative a justice is presumed to be, and the higher the score the more liberal a justice is presumed to be.[15] In a 2003 statistical analysis of Supreme Court voting patterns, Scalia and Justice Thomas emerged as the most conservative.[16][17] However, his originalism occasionally brings results that defy conservative administrations. Judged by results alone, like his colleague Justice Clarence Thomas, Scalia has handed down decisions that might be called liberal in certain cases.

Hamiltonian political principles

In contrast to libertarian conservatives, Scalia has a rather positive view of governmental power. At a 1982 conference on federalism, Scalia challenged conservatives to reexamine what he regarded as their hostile view toward national power. At a time when the presidency and Senate were in the hands of Republicans, Scalia maintained that a "do nothing" approach toward national policymaking was "self-defeating" for purposes of achieving conservative policy goals. Scalia urged the members of the audience— "as Hamilton would have urged you—to keep in mind that the federal government is not bad but good. The trick is to use it wisely."[18] As a judge, Scalia has coupled his positive view of governmental power with a defense of Hamiltonian political principles.

In Court opinions and extra-judicial writings, he has defended a formalistic view of separation of powers, which protects the least powerful institutions from overreaching by Congress, and which gives the executive branch substantial freedom to act with energy. Scalia has defended an energetic executive, whose powers are not limited to the explicit grants of authority under Article II and which is regarded as the sole organ in foreign affairs. He has defended a "political" conception of public administration that rejects the Progressive idea of administration as a neutral science, and he has embraced the three central components of Hamilton's administrative theory—unity, discretion, and policymaking. Scalia has defended a strong and independent federal judiciary, which is unafraid of striking down state and federal laws that conflict with the Constitution, but which is ultimately regarded as the least dangerous branch of government. And Scalia has defended a conception of the U.S. federal system where the federal government’s authority is dominant and the states are primarily protected against federal encroachment by the political process and the structural provisions of the Constitution.[19]

Stare decisis

While Scalia's approach to textual interpretation is famously categorical, his approach to stare decisis is not easily described, not least because originalists have not arrived at a singular answer on stare decisis. In An Originalist Theory of Precedent: Originalism, Nonoriginalist Precedent, and the Common Good, 36 N.M. L. Rev. 419 (2006), Prof. Lee Strang argued, echoing Justice Frankfurter's formulation in Coleman v. Miller,[20] that stare decisis was sufficiently embedded in the common law understanding of courts to be implicit in Article III's grant of the judicial power, which means that originalists must find some account for stare decisis; Scalia's approach is best described as "moderate".

Unlike Justice Thomas, who is prone to reject stare decisis when he feels that a previous case has misinterpreted the Constitution, Scalia has steered a more moderate course. On the one hand, he has called for overruling many entrenched precedents that he considers unprincipled, most notably on abortion, criminal procedure, the Eighth Amendment, and campaign finance regulations.[21] Moreover, having a formalist preference for clear rules rather than malleable balancing tests, as described above, he has rejected certain Court-instituted doctrines. For example in Tennessee v. Lane (2004) he rejected the Congruence and Proportionality test (adopted by the Court seven years earlier for reviewing Congressional enforcements of the Fourteenth Amendment) as a "standing invitation to judicial arbitrariness and policy-driven decisionmaking."[22] However, in his solo dissent in that case, his explanation—"principally for reasons of stare decisis"—of his ultimate choice of a standard to replace Congruence and Proportionality hints at a willingness to allow stare decisis to trump his own judicial philosophy.[22][23] More notably, he has declined to revisit several New Deal-era precedents—on federalism—which according to many originalists unconstitutionally expanded Congress's power and restricted states' powers using overbroad interpretations of the Commerce Clause.[24] This might be explained, however, by Scalia's Hamiltonian political principles and, in particular, his favorable view of national power.

That Scalia would uphold some and overrule other precedents that contradict his judicial philosophy is an apparent inconsistency that has led Scalia's critics to note that the written constitution is not silent on precedent, and they conclude that originalism cannot be reconciled with stare decisis.[25] Scalia has responded that stare decisis is a "pragmatic exception" to, not a part of, originalism.[26] For example, overruling New Deal precedents would be impractical because entrenched Congressional enactments and federal regulations, such as the Social Security Act, would be invalidated (this is, however, the modus operandi encouraged by purists). In any event, it seems Scalia will vote to uphold entrenched statutes even if they may violate originalism (like New Deal legislation), but he will also vote to uphold statutes that violate entrenched precedent as long as they satisfy originalism (like certain regulations on abortion).

Because Scalia's approach to precedent has the intent, if not the effect, of deferring to popularly enacted statutes in many cases, he has drawn praise as a judicial restraintist but criticism as a majoritarian.[27][28][29][30]

Jurisprudence in practice

Rights

Scalia claims to defend rights explicit in the Constitution or recognized by longstanding social or legal traditions, but refuses to enforce other rights on the presumption that the courts are the default vindicators of any claim deemed rightful. One exception to this is the right to privacy, which is not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution but is a long-standing legal tradition. Scalia has said on several occasions that he does not believe the Constitution guarantees a right to privacy. He has vociferously asserted that the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause does not protect abortion (which he thinks is neither prohibited nor protected by the Constitution),[31] sodomy,[32][33] assisted suicide,[34] parental control over child visitation,[35][36] or manufacturers from large punitive damages.[37] With respect to the First Amendment, Scalia has voted to strike down laws restricting "any communicative activity," including flag-burning, cross-burning, campaign contributions, and abortion protests.[4]

With respect to procedural rights, he has resisted his colleagues' attempts to restrict the employment of the death penalty following the Eighth Amendment's prohibition of "cruel and unusual Punishment."[38] He holds that the Constitution does not bar capital punishment of people who were juveniles at the time of the crime, as he was the author of Stanford v. Kentucky, and he dissented in both Thompson v. Oklahoma and Roper v. Simmons. On the Fifth Amendment, Scalia has criticized the Miranda warning.[39] Conversely, he has ardently defended procedural rights explicit in the Constitution, for example arguing in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld (joined in dissent by his usual ideological opponent, Justice Stevens) that the government's detention of a U.S. citizen as an enemy combatant without charge was unconstitutional because Congress had not suspended the writ of habeas corpus. Scalia is similarly wary of government violations of the procedural guarantees of the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Amendments (e.g. the Confrontation Clause in Maryland v. Craig discussed above).

Separation of powers

Regarding the Constitution's allocation of power among the Executive, Legislative and Judicial branches, Scalia favors clear lines of separation over pragmatic considerations. In a 1989 dissent he argued that the U.S. Sentencing Commission, which authorized federal judges to make policy in an executive capacity, violated the separation of power of the Judicial branch from the Executive.[40] In a 1987 dissent he criticized the Independent Counsel law as an unwarranted encroachment on the Executive branch by the Legislative. Justice Scalia has defended a formalistic interpretation of separation of powers primarily on the ground that it will make government officials more accountable and thereby better protect liberty. But there appears to be another reason for Scalia's formalism: to protect the powers of the executive branch. A central purpose of the framers' system of separation of powers was to guard against legislative tyranny, which has not been lost on Justice Scalia. He has said that the doctrine of separation of powers "not only protects, but pre-eminently protects, the Executive obligation to "take care that the Laws be faithfully executed," and he has warned that if government officials (particularly, the members of Congress) do not begin giving "more than lip service" to the doctrine "we will soon find ourselves living not under the Constitution but under a parliamentary democracy...."[41] Some claim there exists a double standard in Justice Scalia's separation of powers jurisprudence, alleging that he has been much less concerned about enforcing a formalistic interpretation of separation of powers when the executive branch's authority is called into question, and that he has shown more concern about congressional conferrals of core legislative power on the executive branch than he has shown about congressional usurpation of core executive functions. The latter, critics claim, was most apparent in his dissenting opinion in Clinton v. City of New York, where he supported (against Presentment Clause objections) the conferral of line-item veto authority on the president.[42]

Administrative law

Scalia was a former Professor of Administrative Law at the University of Chicago. He is very dubious of agency authority to, in his view, create law. As his dissent in the Brand X cable TV ISP case indicates, he was suspicious that the FCC rules to make one service telecommunications service rather than an information service in an arbitrary way by analogizing from the example of home delivered pizza. Scalia reasoned that the majority's view would have courts divide the delivery service apart from the pizza baking service.

Important cases

This section lists cases which form an essential introduction to Scalia's jurisprudence, views and writing style.

- Edwards v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578 (1987) (dissenting)

- United States v. Taylor 487 U. S. 326 (1988) (concurring)

- Morrison v. Olson, 487 U. S. 654 (1988) (dissenting)

- Thompson v. Oklahoma, 487 U. S. 815 (1988)

- Coy v. Iowa, 487 U. S. 1012 (1988) (cf. Maryland v. Craig, 497 U.S. 836 (1990), dissenting)

- Stanford v. Kentucky, 492 U.S. 361 (1989)

- Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989) (concurring)

- Oregon v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872 (1990) (author of majority opinion)

- Rutan v. Republican Party of Illinois, 497 U.S. 62 (1990)

- Harmelin v. Michigan, 501 U. S. 957 (1991) (concurring in part and writing for the Court in part)

- Lee v. Weisman, 505 U. S. 577 (1992) (dissenting)

- Planned Parenthood v. Casey, (dissenting)

- Lamb's Chapel v. Center Moriches School District, 508 U.S. 384 (1993) (concurring)

- Mertens v. Hewitt Associates,

- Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996) (dissenting)

- United States v. Virginia, 518 U. S. 515 (1996) (dissenting)

- Wabaunsee County v. Umbehr, 518 U. S. 668 (1996)

- United States v. Playboy Entertainment Group, 529 U.S. 803 (2000)

- Troxel v. Granville,

- Stenberg v. Carhart, 530 U. S. 914 (2000) (dissenting)

- Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98 (2000)

- PGA Tour, Inc. v. Martin, 532 U.S. 661 (2001) (dissenting)

- Rogers v. Tennessee, 532 U.S. 451 (2001) (dissenting)

- Kyllo v. United States, 533 U.S. 27 (2001)

- Adarand Constructors v. Peña, 515 US 200 (1995) (concurring)

- Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002) (dissenting)

- McConnell v. Federal Elections Commission, 540 U. S. 93 (2003)

- Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U. S. 558 (2003), (dissenting)

- Hamdi v. Rumsfeld 542 U. S. 507 (2004), (dissenting, joined by Justice John Paul Stevens)

- Crawford v. Washington, 541 US 36 (2004)

- Roper v. Simmons, (dissenting)

- Brand X, (dissenting)

- Gonzales v. Raich, Docket No. 03-1454, (concurring)

- McCreary County v. ACLU of Kentucky, Docket No. 03-1693, (dissenting)

- District of Columbia v. Heller, Docket No. 07-290 (author of majority opinion)

- 2005 Term

- Gonzales v. Oregon, (dissenting)

- Georgia v. Randolph, (dissenting)

- Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, (dissenting)

- 1986 Term

- American Trucking Associations v. Scheiner, (dissenting)

Sixth Amendment case study

There is a particularly striking line of cases, beginning in 1989 and reaching its logical conclusion in 2005 with Booker, which illustrates Scalia's writing style and views on a particular subject, viz., the requirement that a jury must determine all facts which relate to a sentence, a Constitutional guarantee which endangered (in Blakely) and then led to the toppling (in Booker) of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines as the sole means of determining a sentence for a federal crime. That line of cases is as follows:

- Mistretta v. United States, 488 U.S. 361 (1989) (dissenting)

- Neder v. United States, (dissenting)

- Apprendi v. New Jersey, (concurring)

- Harris v. United States, (concurring)

- Ring v. Arizona, (concurring)

- Blakely v. Washington,

- Schriro v. Summerlin,

- United States v. Booker (concurring in part and dissenting in part)

(Refer to Morano, "Justice Scalia: His Instauration of the Sixth Amendment in Sentencing" for pre-Booker discussion of this line of cases).

Judicial temperament and personality

Scalia's approach to textual interpretation is not the only substantial change he has brought to the bench. In a position that has often been characterized by substantial circumspection in writing and public behavior, Scalia has been especially willing to display his personality and wit and to attract, if not embrace, public controversy. Scalia is sometimes referred to by the nickname "Nino", and his colleagues refer to the frequent short case-related memos he sends as Ninograms.[43]

Despite ideological differences, he is socially friendly with Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who considers Scalia her closest confidant and colleague, and keeps in her office pictures of herself and Scalia together at the Washington Opera and on a trip to India.[44][45]

At oral argument and in written opinions

Scalia is well known for his lively questioning during arguments before the court; one litigator who argued before the Court compared Scalia's questioning style to "a big cat batting around a ball of yarn."[46] It has been observed that his aggressive questioning style at oral argument was virtually unknown upon his arrival at the Court, but has become virtually the norm in the succeeding twenty years as new Justices arrived.

In his concurring and dissenting opinions, he frequently refers to fellow Justices personally, quoting them from past opinions to point out what he considers inconsistencies in their reasoning or broad judicial philosophy, or accusing them of inventing legal standards out of thin air. "[Alt]hough Scalia's judicial philosophy resemble[s] that of Hugo Black, his temperament [i]s closer to that of William O. Douglas, and that proved to be his undoing." Rosen, The Supreme Court 183 (2007). His strongest commentary has often been directed at his more moderate fellow conservatives, Justices Sandra Day O'Connor and Anthony Kennedy, for reasons including what he saw as the former's equivocation on abortion and the latter's willingness to take persuasive guidance from foreign law in his opinions.[47] His written opinions are also known, in the context of judicial custom, for their unusually commonplace phrasing. The combination of Scalia's often pointed, uncompromising and corrosive writing with his layman approach to penmanship have led some to deduce an intention of influencing future lawyers and legal practitioners to accord with his judicial philosophy.[48] Already affecting legal discourse and practice is Scalia's persistent criticism of the use of legislative history in statutory interpretation, according to Judge Alex Kozinski, who has said that "legislative history just ain't worth what it was a few years ago."[49] Scalia has even earned respect from political liberals; Senate Democratic leader Harry Reid has said, "[T]his is one smart guy. And I disagree with many of the results that he arrives at, but his reason for arriving at those results are very hard to dispute."[50][51] Others have commented that Justice Scalia's aggressive criticisms of Justices Kennedy and O'Connor may have diminished the willingness of those Justices to form a stable conservative coalition on the Court.[52]

Relations with the electronic media

Strongly protective of his privacy, Scalia formerly severely restricted the electronic media from recording his speaking engagements, citing his "First Amendment right not to speak on the radio or television when I do not wish to do so."

In April 2004, at a Scalia speech in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, U.S. Marshal Melanie Rube, acting as security detail, confiscated the audio tape of a reporter covering the event. After some controversy over the incident, Scalia apologized and stated he did not order the Marshal to do so. He has since amended his policy so that print reporters are now allowed to record his speeches to "promote accurate reporting."

More recently, he appears to be relaxing the electronic media stricture as well—at least two of his recent speeches have been covered by C-SPAN. This is possibly related to the graduation from college of the last of his children, whose privacy has potentially been a factor in Scalia's desire for privacy (see discussion in Mark Tushnet, A Court Divided), and Scalia has recently been quoted as saying that "My kids have been working on me to get out and do more public appearances...They think it makes it harder to demonize you—and I agree."[53]

Views on televising Supreme Court sessions

Like Justice Souter—who has averred that "the day you see a camera come into our courtroom, it's going to roll over my dead body"[54][55]—Scalia has opposed the introduction of live television broadcasts of Supreme Court oral arguments. In an early 2005 roundtable discussion with Justices O'Connor and Breyer at the National Archives, also carried by C-SPAN, he noted that he would approve of both audio and television broadcasts if he could be confident that it would go out and be watched gavel-to-gavel. He characterized his objections as relating to the possibility for sensationalism, excerptation, and the fostering of an inaccurate picture of the Supreme Court's operation.

Recusals and non-recusals

Perhaps more than any other recent Justice, Scalia's choices regarding whether to recuse himself from upcoming cases following controversial statements and acts have garnered public attention.

- Scalia did recuse himself in one case, Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow, following public comments in Virginia while the case was pending that were characterized (by the Mayor who introduced Scalia at the appearance) as making it "clear that he [Scalia] thought anyone who did not want school children to say the Pledge of Allegiance with the words 'under God' in it deserved a spanking."[56] It is not universally accepted that Scalia was under any obligation to do so, and in light of subsequent events, some have suggested that he should not have done so.[57]

- Scalia refused, however, to recuse himself in the case of Cheney v. United States District Court for the District of Columbia, a case dealing with the right of the Vice-President to keep secret the membership of an advisory task force on energy policy. Scalia was asked to recuse because he had previously gone on a hunting trip with various persons including Cheney; Scalia refused, and took the relatively uncommon step of defending his refusal to recuse himself from the case with a public memorandum, focusing on the distinction between official capacity and personal capacity suits, and concluding that because Vice President Cheney was sued in his official capacity, any personal relationship that existed between the two men was irrelevant to Scalia's ability to render an impartial judgment. "I do not believe my impartiality can reasonably be questioned," concluded Scalia.[58] Scalia, concurring with the majority, supported Cheney's position in the case.

- Scalia was again asked to recuse from Hamdan v. Rumsfeld. While the case was pending before the court, Scalia answered a question during a Q&A session at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland, where he rejected in principle that detainees at Guantanamo Bay have the right to be tried in civil courts. Having noted that the Constitution applies to Americans the world over and to all persons in the United States, Scalia explicitly rejected the notion that the Constitution protects non-Americans outside of the United States, and added:

-

- War is war, and it has never been the case that when you captured a combatant you have to give them a jury trial in your civil courts. Give me a break. If he was captured by my [America's] army on a battlefield, that is where he belongs.

- Also of concern to those petitioning for recusal in Hamdan was an additional comment that "I had a son [Matthew Scalia] on that battlefield; they were shooting at my son, and I'm not about to give this man who was captured in a war a full jury trial." Scalia declined to recuse himself from Hamdan, this time without comment.[59][60]

This incident led law professor and conservative commentator Ron Cass to complain that it was becoming fashionable in certain circles for those who oppose Scalia to demand that Scalia recuse himself as a strategy to nullify his vote.[61]

Views on the death penalty

Antonin Scalia delivered a speech at the University of Chicago Divinity School in 2002 expressing his views on the subject of the death penalty. In a speech refuting many common lines of thought, Scalia declares himself neutral on the death penalty, but defends its usage as not being immoral.[62]

| “ | This is not the Old Testament, I emphasize, but St. Paul.... [T]he core of his message is that government—however you want to limit that concept—derives its moral authority from God.... Indeed, it seems to me that the more Christian a country is the less likely it is to regard the death penalty as immoral.... I attribute that to the fact that, for the believing Christian, death is no big deal. Intentionally killing an innocent person is a big deal: it is a grave sin, which causes one to lose his soul. But losing this life, in exchange for the next?... For the nonbeliever, on the other hand, to deprive a man of his life is to end his existence. What a horrible act!... The reaction of people of faith to this tendency of democracy to obscure the divine authority behind government should not be resignation to it, but the resolution to combat it as effectively as possible. We have done that in this country (and continental Europe has not) by preserving in our public life many visible reminders that—in the words of a Supreme Court opinion from the 1940s—"we are a religious people, whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being."... All this, as I say, is most un-European, and helps explain why our people are more inclined to understand, as St. Paul did, that government carries the sword as "the minister of God," to "execute wrath" upon the evildoer." | ” |

Further reading

- Ring, Kevin A., Scalia Dissents: Writings of the Supreme Court's Wittiest, Most Outspoken Justice (Regnery Publishing, Inc., November 25, 2004); ISBN 0-89526-053-0

- Rossum, Ralph, Antonin Scalia's Jurisprudence: Text and Tradition (University Press of Kansas, Feb. 6, 2006); ISBN 0-7006-1447-8

- Scalia, Antonin, and Amy Gutmann, ed., A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law (Princeton, July 27, 1998); ISBN 0-691-00400-5

- Staab, James B. The Political Thought of Justice Antonin Scalia: A Hamiltonian on the Supreme Court (Rowman & Littlefield, 2006) (ISBN 0-7425-4311-0).

- Tushnet, Mark, A Court Divided (W. W. Norton & Company, January 30, 2005); ISBN 0-393-05868-9

Notes

- ↑ Antonin Scalia from Notable Names Database

- ↑ Supreme Court Historical Society

- ↑ Talbot, Margaret. "Profiles, Supreme Confidence", The New Yorker, March 28, 2005, p. 40. Accessed October 22, 2007. "Tells about Scalia’s childhood in Trenton, New Jersey and Elmhurst Queens. His father, Eugene, was a professor at Brooklyn College and a believer in the principles of the New Criticism."

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 "Scalia Speaks in Ames, Scolds Aggressive Student", Harvard Law Record (2006-12-07). Retrieved on 2008-10-26.

- ↑ Rick Perlstein, Nixonland, 2008, p. 596.

- ↑ Religious affiliation of Supreme Court justices Justice Sherman Minton converted to Catholicism after his retirement.

- ↑ A Matter of Interpretation, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Ring, p. 2.

- ↑ "Souter Anchoring the Court's New Center", New York Times (1992-07-03). Retrieved on 2008-06-27.

- ↑ William Eskridge, Politics without Romance: Implications of Public Choice Theory for Statutory Interpretation, Virginia Law Review, Vol. 74, No. 2, p. 277.

- ↑ "Why Learned Hand Would Never Consult Legislative History Today," Harvard Law Review, Vol. 105, No. 5 (March 1992), p. 1005.

- ↑ Cass Sunstein, "Justice Scalia's Democratic Formalism," The Yale Law Journal, Vol. 107, No. 2 (Nov. 1997), p. 530.

- ↑ 56 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1175

- ↑ Boston News March 15 2006 http://www.boston.com/news/local/massachusetts/articles/2006/03/15/scalia_critical_of/

- ↑ http://ws.cc.stonybrook.edu/polsci/jsegal/qualtable.pdf

- ↑ See http://pooleandrosenthal.com/the_unidimensional_supreme_court.htm .

- ↑ Lawrence Sirovich, "A Pattern Analysis of the Second Rehnquist Court," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100 (24 June 2003), available online at http://www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/1132164100v1 .

- ↑ Antonin Scalia, "The Two Faces of Federalism," Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy 6 (1982): 19–22.

- ↑ James B. Staab, The Political Thought of Justice Antonin Scalia: A Hamiltonian on the Supreme Court, pp. xxiv-xxxi.

- ↑ Coleman v. Miller 307 U.S. 433, 460 (1939) (Frankfurter, concurring) ("In endowing [the Federal] Court[s] with 'judicial Power' the Constitution presupposed an historic content for that phrase ... Both by what they said and by what they implied, the framers of the Judiciary Article gave merely the outlines of what were to them the familiar operations of the English judicial system and its manifestations on this side of the ocean before the Union").

- ↑ See, e.g., Scalia's opinions in Stenberg v. Carhart (calling for overruling Planned Parenthood v. Casey), Dickerson v. United States (calling for overruling Miranda v. Arizona), and South Carolina v. Gathers (calling for overruling Booth v. Maryland), and Justice Thomas's opinion which Scalia joined in Randall v. Sorrell (calling for overruling Buckley v. Valeo).

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 FindLaw for Legal Professionals - Case Law, Federal and State Resources, Forms, and Code

- ↑ Cf. Rossum, p. 97.

- ↑ See, e.g., Justice Thomas's opinions in Gonzales v. Raich and Hillside Dairy v. Lyons, which Scalia declined to join.

- ↑ Laurence Tribe in Antonin Scalia and Amy Guttman, A Matter of Interpretation, Princeton (1998), p. 83.

- ↑ Scalia in ibid., p. 140.

- ↑ Randy Barnett at http://volokh.com/archives/archive_2005_06_26-2005_07_02.shtml#1119812379 (by implication, referring to the "[un]willingness" of a "majoritarian like Scalia" to "judicially enforce federalism limitations on Congress").

- ↑ Adam Pritchard and Todd Zywicki, "Finding the Constitution: An Economic Analysis of Tradition's Role in Constitutional Interpretation," North Carolina Law Review, Vol. 77, 1998 SSRN 141857 ("Justice Scalia has articulated a majoritarian view of tradition that looks to the legislative practices of state legislatures").

- ↑ Ralph A. Rossum at http://www.claremont.org/writings/crb/fall2005/correspondence.html ("...Scalia has a 'vulgar majoritarian' understanding of democracy").

- ↑ James Huffman, "A Case for Principled Judicial Activism," Heritage Foundation Lecture #456 (20 May 1993), available online at http://www.heritage.org/Research/LegalIssues/HL456.cfm (characterizing Scalia as a "judicial restraintist" by implication, and asking "Why should the judiciary defer to democracy, as Justice Scalia would have it?").

- ↑ "Scalia Says Constitution Does Not Prohibit, Permit Abortion Rights", Medical News Today (2008-04-29). Retrieved on 2008-10-26.

- ↑ FIRST THINGS: A Journal of Religion, Culture, and Public Life

- ↑ NINOVILLE - an Antonin Scalia reference site

- ↑ See, e.g., Washington v. Glucksberg.

- ↑ Ring, p. 314.

- ↑ See Troxel v. Granville where Scalia explained that, while he recognized in the Ninth Amendment the right to direct the upbringing of one's children, the courts had no authority to invalidate duly passed laws violating that right. He contended that, instead, the legislature was not the proper venue for arguing against infringement of the right.

- ↑ See BMW v. Gore.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ See Dickerson v. United States.

- ↑ Ring, pp. 43-44

- ↑ David Ryrie Brink, Antonin Scalia, and Richard B. Smith, Brief for American Bar Association as Amicus Curiae in INS v. Chadha, and "1976 Bicentennial Institute--Oversight and Review of Agency Decisionmaking," Administrative Law Review (1976) 28 (No. 4): 569-742, 694.

- ↑ James B. Staab. The Political Thought of Justice Antonin Scalia: A Hamiltonian on the Supreme Court,pp. 35-88.

- ↑ Edward Lazarus, C-SPAN Booknotes, "Closed Chambers: The First Eyewitness Account of the Epic Struggles Inside the Supreme Court", June 14, 1998. Retrieved Nov. 29, 2006.

- ↑ Oyez.org, "Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg's Chambers: At the Opera". Retrieved Mar. 11, 2007.

- ↑ Oyez.org, "Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg's Chambers: Scalia & Ginsburg on elephant". Retrieved Mar. 11, 2007.

- ↑ OYEZ Biography http://www.oyez.org/oyez/resource/legal_entity/103/print

- ↑ See, e.g., Bill Adair, "Spirited Scalia not one to shy away," St. Petersburg Times (Florida), April 25, 2004.

- ↑ Joan Biskupic at http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/2002-09-17-scalia-1acover_x.htm "No Shades of Gray for Scalia" in USA Today

- ↑ *Judge Alex Kozinski, "My Pizza With Nino," 12 Cardozo L. Rev. 1583 (1991)

- ↑ Meet the press, Dec. 5, 2004.

- ↑ Richey, Warren, "One scenario: Chief Justice Scalia?", Christian Science Monitor, May 13, 2005.

- ↑ Savage, David, "Supreme Court's new tilt could put Scalia on a roll," Los Angeles Times, Feb. 20, 2007.

- ↑ Celebrity Scandals and Gossip - NY Daily News

- ↑ Harper, Liz. Profile: Justice David H. Souter. The Online Newshour. Retrieved Aug. 24, 2008.

- ↑ AP. On Cameras in Supreme Court, Souter Says, 'Over My Dead Body'. New York Times. Mar. 30, 1996. Retrieved Aug. 24, 2008

- ↑ Tony Mauro, Legal Times, "Scalia Recusal Revives Debate Over Judicial Speech, Ethics", October 20, 2003. Retrieved Nov. 29, 2006.

- ↑ Brian T. Fitzpatrick, The National Law Journal, "Scalia's mistake", April 24, 2006. Retrieved Nov. 29, 2006.

- ↑ "CHENEY v. UNITED STATES DIST. COURT FOR D. C.", March 18, 2004. Retrieved Nov. 29, 2006.

- ↑ BBC News, "Judge 'rejects Guantanamo rights'", 27 March 2006. Retrieved Nov. 29, 2006.

- ↑ Mark Coultan, Sydney Morning Herald, "Comments on rights of detainees cast doubt on judge's role on court", March 28, 2006. Retrieved Nov. 29, 2006.

- ↑ Ronald A. Cass, Real Clear Politics, "Stalking Scalia", March 30, 2006. Retrieved Nov. 29, 2006.

- ↑ Scalia, Antonin. God's Justice and Ours. First Things. May, 2002. pp. 17-21. Retrieved Aug. 24, 2008

References

- Gordon, Robert (November 1, 2005). "Alito or Scalito?". Slate.

External links

Biographical

- Official Supreme Court biography (PDF)

- Biography from the Oyez Project

- Biography from the Supreme Court Historical Society

- Biography from About.com

- A Profile of Scalia, from the Christian Science Monitor (1998)

- Judge Alex Kozinski, My Pizza With Nino, 12 Cardozo L. Rev. 1583 (1991)

Websites

- Ninoville - general repository of speeches and written materials; nascent index of Scalia opinions.

- Cult of Scalia — fan site

- Open Directory Project — Antonin Scalia directory category

- Yahoo — Antonin Scalia directory category

Works by Scalia

- Making Your Case: The Art of Persuading Judges -- Co-authored with Bryan A. Garner -- Thomson West

- God's Justice & Ours (discussing Catholicism and the Death Penalty)

- Law & Language (reviewing Steven D. Smith's book Law’s Quandary)

- Originalism: The Lesser Evil (57 U. Cin. L. Rev. 849) (1989)

- Scalia lecture at Univ. of Georgia School of Law, 1989

- Scalia lecture at the Catholic Univ. of America, 1996

- A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law (ISBN 0-691-00400-5)

Periodical articles and miscellaneous content

- Antonin Scalia considers the meaning of golf - Article at Everything2.

- Supreme Confidence By Margaret Talbot, and Related interview

- No Shades of Grey

- "Scaliapalooza" by Dahlia Lithwick

- The Souter Factor

- So, Guy Walks Up to the Bar, and Scalia Says... - study concludes Scalia is funniest justice

- Antonin Scalia and the Case of the Albemarle Pippins

- Associate Justice Scalia on Guantanamo Bay

- What Would Aristotle Make Of Scalia? by Michael Frost.

- The Wit and Wisdom of Justice Scalia, by Ralph A. Rossum, Claremont Review of Books (on two books that collect Scalia's opinions, dissents, and concurrences)

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Roger Robb |

Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit 1982-1986 |

Succeeded by David B. Sentelle |

| Preceded by William Hubbs Rehnquist |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1986 - present |

Incumbent |

| Order of precedence in the United States of America | ||

| Preceded by John Paul Stevens Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States |

United States order of precedence Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States |

Succeeded by Anthony Kennedy Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States |

|

||||||||||||||

| Supreme Court of the United States | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Scalia, Antonin Gregory |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Supreme Court Associate Justice |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 11, 1936 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Trenton, New Jersey |

| DATE OF DEATH | |

| PLACE OF DEATH | |