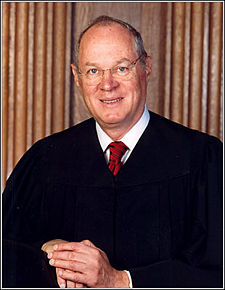

Anthony Kennedy

|

Anthony McLeod Kennedy

|

|

|

|

|

Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court

|

|

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office February 18 1988 |

|

| Nominated by | Ronald Reagan |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | Lewis Franklin Powell, Jr. |

|

|

|

| Born | July 23, 1936 Sacramento, California |

| Spouse | Mary Davis Kennedy |

| Alma mater | Stanford University |

| Religion | Roman Catholic[1] |

Anthony McLeod Kennedy (born July 23, 1936) has been an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court since 1988. Appointed by Republican President Ronald Reagan, he acts as the Court's swing vote on social issues in some cases and has consequently held special prominence in some politically-charged 5–4 decisions.

Contents |

Personal history

Kennedy is not related to the Kennedy family of American politics. He grew up in Sacramento, California as the son of a prominent attorney and as a boy, he therefore came into contact with prominent attorneys such as Earl Warren. He served as a page in the California State Senate as a youngster.[2]

He received his B.A. in Political Science from Stanford University in 1958. He also spent part of his undergraduate time his senior year at the London School of Economics[2] before earning an LL.B from Harvard Law School in 1961.

Kennedy was in private practice in San Francisco, California, from 1961-1963, then took over his father's practice in Sacramento, California, from 1963-1975 following his father's death.[2] From 1965 to 1988, he was a Professor of Constitutional Law at University of the Pacific, McGeorge School of Law and currently continues teaching law students (including legal seminars during McGeorge's European summer sessions in Salzburg, Austria). He remains Pacific McGeorge's longest-serving active faculty member.

During Kennedy's time as a California legal professor and attorney, he assisted then-California Governor Ronald Reagan with drafting a state tax proposal.[2]

Kennedy has served in numerous positions during his career, including the California Army National Guard in 1961 and the board of the Federal Judicial Center from 1987-1988. He also served on two committees of the Judicial Conference of the United States: the Advisory Panel on Financial Disclosure Reports and Judicial Activities (subsequently renamed the Advisory Committee on Codes of Conduct) from 1979-1987, and the Committee on Pacific Territories from 1979-1990, which he chaired from 1982-1990. He was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit by President Gerald Ford in 1975, upon the recommendation of Reagan.[2]

Appointment

Kennedy was nominated to the Supreme Court after Reagan's failed attempts at placing Robert Bork and Douglas Ginsburg there.[3][4]

While vetting Kennedy for potential nomination, some of Reagan's Justice Department lawyers said Kennedy was too eager to put courts in disputes many conservatives would rather leave to legislatures, and to identify rights not expressly written in the Constitution.[5] Kennedy's stance in favor of privacy rights drew criticism; Kennedy cited Roe v. Wade and other privacy right cases favorably, which one lawyer called "really very distressing".[6]

In another of the opinions Kennedy wrote before coming to the Supreme Court, he criticized (in dissent) the police for bribing a child into showing them where the child's mother hid her heroin; Kennedy wrote that "indifference to personal liberty is but the precursor of the state's hostility to it."[7] The Reagan lawyers also criticized Kennedy for citing a report from Amnesty International to bolster his views in that case.[7]

Another lawyer pointed out "Generally, [Kennedy] seems to favor the judiciary in any contest between the judiciary and another branch."[7]

Kennedy endorsed Griswold as well as the right to privacy, calling it "a zone of liberty, a zone of protection, a line that's drawn where the individual can tell the Government, 'Beyond this line you may not go.'"[8] This gave Kennedy more bipartisan support than Bork and Ginsburg. The Senate confirmed him by a vote of 97 to 0.[8]

Supreme Court tenure

Ideology

Appointed by a Republican president, Kennedy’s tenure on the Court has seen him take a somewhat mixed ideological path; he usually takes a conservative viewpoint, but sometimes has looked at cases individually.[2]

Kennedy, or Sandra Day O'Connor, or both of them, have served as one of two swing voters in many 5-4 decisions during the Rehnquist and Roberts Courts. On issues of religion, he holds to a far less separationist reading of the Establishment Clause than did Sandra Day O'Connor, favoring a "Coercion Test" that he detailed in County of Allegheny v. ACLU.

Kennedy supports a broad reading of the "liberty" protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which means he supports a constitutional right to abortion in principle, though he has voted to uphold several restrictions on that right, including laws to prohibit partial-birth abortions. He is "tough on crime" and opposes creating constitutional restrictions on the police, especially in Fourth Amendment cases involving searches for illegal drugs, although there are some exceptions, such as his concurrence in Ferguson v. City of Charleston. He opposes affirmative action as promoting stereotypes of minorities. He also takes a very broad view of constitutional protection for speech under the First Amendment, invalidating a congressional law prohibiting "virtual" child pornography in the 2002 decision, Ashcroft v. ACLU.[9]

Abortion

In 1990, Justice Kennedy upheld a restriction on abortion for minors; it required both parents to consent to the procedure. The case was Hodgson v. Minnesota.

In 1992, he joined Justice Sandra Day O'Connor's controlling plurality opinion in the case of Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), which re-affirmed in principle (though not in many details) the Roe v. Wade decision recognizing the right to abortion under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The plurality opinion, signed jointly by three justices appointed by the anti-Roe presidential administrations of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, ignited a firestorm of criticism from conservatives. Kennedy had stated at least as early as 1989 that, in order to uphold precedent, he might not overrule Roe; he had also taught Roe as a professor for fifteen years.[10] At the same time, Kennedy reportedly had considered overturning Roe, according to court insiders, but in the end decided to uphold restrictions without overturning precedent.[11]

In later abortion decisions, it became apparent that Kennedy thought Casey had narrowed the Roe decision and allowed more restrictions. Because of a changed composition on the Court under President Clinton, Kennedy was no longer the fifth vote to strike down abortion restrictions. Thus, O'Connor became the Justice who defined the meaning of Casey in subsequent cases while Kennedy was relegated to dissents in trying to explain what he thought the Casey holding meant. For example, Kennedy dissented in the 2000 decision of Stenberg v. Carhart, which struck down laws criminalizing partial-birth abortion.

After the judicial appointments of President George W. Bush, Justice Kennedy again became the needed fifth vote to strike down abortion restrictions. Since Kennedy's conception of abortion rights is more narrow than O'Connor's, this has led to a slightly more lenient review of abortion restrictions since 2006. Kennedy wrote the majority opinion in 2007's Gonzales v. Carhart, which held that a federal law criminalizing partial birth abortion did not violate the principles of Casey because it did not impose an "undue burden." The decision did not expressly overrule Stenberg, although many commentators see it having that effect.[1]

Gay rights and homosexuality

Kennedy has often taken a strong stance in favor of expanding Constitutional rights to cover sexual orientation. He wrote the Court's opinion in the controversial 1996 case, Romer v. Evans, invalidating a provision in the Colorado Constitution denying homosexuals the right to bring local discrimination claims. In 2003, he authored the Court's opinion Lawrence v. Texas, which invalidated criminal prohibitions against homosexual sodomy under the Due Process Clause of the United States Constitution, overturning the Court's previous contrary ruling in 1986's Bowers v. Hardwick. In doing so, however, he was very careful to limit the extent of the opinion, declaring that the case did not involve whether the government must give formal recognition to any relationship that homosexual persons seek to enter. In both cases, he sided with the more liberal members of the Court. Lawrence also controversially referred to foreign laws, specifically ones enacted by the Parliament of the United Kingdom and the European Court of Human Rights, in justifying its result. Kennedy voted, with 4 other Justices, to uphold the Boy Scouts of America's organizational right to ban homosexuals from being scoutmasters in Boy Scouts of America v. Dale in 2000.

Capital punishment

Kennedy has generally voted to restrict the use of the death penalty. With the Court's majority in Atkins v. Virginia and Roper v. Simmons, he held unconstitutional the execution of the mentally ill and those under 18 at the time of the crime. However, in Kansas v. Marsh, he declined to join the dissent, which questioned the overall "soundness" of the existing capital punishment system. His opinion for the Court in Roper, as in Lawrence, made extensive reference to international law, drawing the ire of then-House Majority Leader Tom DeLay who called Kennedy's opinion "incredibly outrageous" but stopped short of calling for his impeachment.

On June 25, 2008, Kennedy authored the 5-4 majority opinion in Kennedy v. Louisiana. The opinion, which was joined by the court's four more liberal judges, held that "[t]he Eighth Amendment bars Louisiana from imposing the death penalty for the rape of a child where the crime did not result, and was not intended to result, in the victim's death." The opinion went on to state, "The court concludes that there is a distinction between intentional first-degree murder, on the one hand, and non-homicide crimes against individuals, even including child rape, on the other. The latter crimes may be devastating in their harm, as here, but in terms of moral depravity and of the injury to the person and to the public, they cannot compare to murder in their severity and irrevocability." The opinion concluded that in cases of crimes against individuals, "the death penalty should not be expanded to instances where the victim's life was not taken." Thus, this ruling is expected to effectively limit the use of the death penalty for a crime against an individual not involving murder. However, it is important to note that this decision is unlikely to impact the use of the death penalty in relation to military justice or for crimes against the state such as terrorism, espionage, or treason.

Conservative commentator Matthew Continetti called the 2008 Kennedy v. Louisiana ruling, which held that the death penalty could not be applied to lesser crimes than homicide, "appalling," writing, "The intellectual backflips Justice Kennedy performed in his opinion would be impressive if they weren't so offensive to constitutionalist sensibilities."[12]

Gun control

Kennedy most recently ruled on June 26, 2008, with the majority in District of Columbia v. Heller, striking down the ban on handguns in the District of Columbia. At issue in the case was whether Washington, D.C.'s ban violated the right to "keep and bear arms" by preventing individuals -- as opposed to state militias -- from having guns in their homes. Kennedy's decision had him siding with the traditionally "conservative" side of the court. The decision came the day after the Court's ruling in Kennedy v. Louisiana, in which Kennedy sided with the traditionally liberal justices.

Habeas Corpus

On June 12, 2008, Kennedy wrote the 5-4 majority opinion in Boumediene v. Bush. The case challenged the legality of Boumediene’s detention at the Guantanamo Bay military base as well as the constitutionality of the Military Commissions Act (MCA) of 2006. He was joined by the four more liberal judges in finding that the constitutionally guaranteed right of habeas corpus applies to persons held in Guantanamo Bay and to persons designated as enemy combatants on that territory. They also found that the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005 failed to provide an adequate substitute for habeas corpus and that the MCA was an unconstitutional suspension of that right.[13][14][15][16]

The Court also concluded that the detainees are not required to exhaust review procedures in the court of appeals before pursuing habeas corpus actions in the district court. In the majority ruling Justice Kennedy called the Combatant Status Review Tribunals "inadequate."[13][14][15][16] He explained, “to hold that the political branches may switch the constitution on or off at will would lead to a regime in which they, not this court, 'say what the law is.'”[17] The decision struck down section seven (7) of the MCA but left intact the Detainee Treatment Act. In a concurring opinion, Justice Souter stressed the fact that the prisoners involved have been imprisoned for as many as six years.[18]

Other issues

On the issue of the limits of free speech, Kennedy joined a majority to uphold the protection of flag burning in the controversial case of Texas v. Johnson.[19] Kennedy would write that "It is poignant but fundamental that the flag protects those who hold it in contempt."[20]

Kennedy has joined with Court majorities in decisions favoring states' rights and invalidating federal and state affirmative action programs. He ruled with the majority on Equal Protection grounds in the controversial 2000 Bush v. Gore case that ceased continuing recounts in the 2000 presidential election and ended the legal challenge to the election of President George W. Bush.

In the 2005 Gonzales v. Raich case, he joined the liberal members of the Court (along with conservative Justice Scalia) in permitting the federal government to prohibit the use of medical marijuana, even in states in which it is legal.[21] Several weeks later, in the controversial case of Kelo v. City of New London (2005), he joined the four more liberal justices in supporting the local government's power to take private property for economic development through the use of eminent domain.[22]

Analysis of Supreme Court tenure

Kennedy has reliably issued conservative rulings during most of his tenure, having voted with William Rehnquist as often as any other justice from 1992 to the end of the Rehnquist Court in 2005.[23] In his first term on the court, Kennedy voted with Rehnquist 92 percent of the time - more than any other justice.[23]

According to legal writer Jeffrey Toobin, starting in 2003, Kennedy also became a leading proponent of the use of foreign and international law as an aid to interpreting the United States Constitution.[24] Toobin sees this consideration of foreign law as the biggest factor behind Kennedy's occasional breaking with his most conservative colleagues.[24] The use of foreign law in Supreme Court opinions dates back to at least 1829, though according to Toobin, its use in interpreting the Constitution on "basic questions of individual liberties" began only in the late 1990s.[25] Especially after 2005, when Sandra Day O'Connor, who had previously been known as the court's "swing vote", retired, Kennedy began to get that title for himself. Kennedy is more conservative than former Justice O'Connor was on issues of race, religion, and abortion, and intensely dislikes being labeled a "swing vote."[23]

Conservative Criticism

Kennedy attracts the ire of conservatives when he does not vote with his more rightist colleagues. According to legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin, conservatives view Kennedy's pro-gay-rights and pro-abortion rulings as betrayals.[24] In 2005, associate professor of law David M. Wagner called Kennedy "The worst of Ronald Reagan's appointees to the Court", and claimed he abandoned his conservative principles beginning in the 1990s in order to gain "the plaudits of the media and the Georgetown A-list."[26] In 2008, conservative commentator Rich Lowry called Kennedy the Supreme Court's "worst justice", writing that his written opinions "have nothing whatsoever to do with the Constitution", and amount to "making it up as he goes along."[27] According to legal reporter Jan Crawford Greenburg, the "bitter" quality of some movement conservatives' views on Kennedy stems from his eventual rethinking of positions on abortion, religion, and the death penalty (which Kennedy believes should not be applied to juveniles or the mentally challenged).[28]

Outside activities

Kennedy has been active off the bench as well, calling for reform of overcrowded American prisons in a speech before the American Bar Association. He spends his summers in Salzburg, Austria, where he teaches international and American law at the University of Salzburg for the McGeorge School of Law international program and often attends the large yearly international judges conference held there. Defending his use of international law, Kennedy told the September 12, 2005, issue of The New Yorker, "Why should world opinion care that the American Administration wants to bring freedom to oppressed peoples? Is that not because there’s some underlying common mutual interest, some underlying common shared idea, some underlying common shared aspiration, underlying unified concept of what human dignity means? I think that’s what we’re trying to tell the rest of the world, anyway.”

Justice Kennedy is one of twelve Catholic justices – out of the 110 total – in the history of the Supreme Court.[29]

References

- ↑ Anthony Kennedy from Notable Names Database

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Christopher L. Tomlins (2005). The United States Supreme Court. Houghton Mifflin. http://books.google.com/books?id=Fy8DjOIxDm0C. Retrieved on 2008-10-21.

- ↑ Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Pages 53-60.

- ↑ http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B0DE1D8103FF933A05752C1A961948260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all

- ↑ Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 53.

- ↑ Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 54.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 55.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Greenhouse, Linda. Becoming Justice Blackmun. Times Books. 2005. Page 189.

- ↑ FindLaw for Legal Professionals - Case Law, Federal and State Resources, Forms, and Code

- ↑ Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 80.

- ↑ Savage,James. Turning Right: The Making of the Rehnquist Supreme Court.1993. John Wiley & Sons. Pages 268-269, 288, 466-471

- ↑ An Indecent Decision, Matthew Continetti, The Weekly Standard, July 7, 2008

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Mark Sherman (June 12 2008). "High Court: Gitmo detainees have rights in court", Associated Press. Retrieved on 2008-06-12. "The court said not only that the detainees have rights under the Constitution, but that the system the administration has put in place to classify them as enemy combatants and review those decisions is inadequate." mirror

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Mark Sherman (June 12 2008). "Terror suspects can challenge detention: U.S. Supreme Court", Globe and Mail. Retrieved on 2008-06-12.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Mark Sherman (June 12 2008). "High Court sides with Guantanamo detainees again", Montorey Herald. Retrieved on 2008-06-12.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 James Oliphant (June 12 2008). "Court backs Gitmo detainees", Baltimore Sun. Retrieved on 2008-06-12. mirror

- ↑ Stuck with Guantánamo (The Economist)

- ↑ "Boumediene et al. v. Bush -- No. 06–1195" (PDF), Supreme Court of the United States (June 12 2008). Retrieved on 2008-06-15.

- ↑ Eisler, Kim Isaac (1993). A Justice for All: William J. Brennan, Jr., and the decisions that transformed America. Page 277. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671767879

- ↑ Eisler, 277

- ↑ Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 17.

- ↑ Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 18.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court. 2007. Penguin Books. Page 163.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Swing Shift: How Anthony Kennedy’s passion for foreign law could change the Supreme Court, Jeffrey Toobin, The New Yorker, September 12, 2005

- ↑ http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2005/09/12/050912fa_fact

- ↑ Beyond "Strange New Respect", David M. Wagner, The Weekly Standard, March 14, 2005

- ↑ America's Worst Justice, Rich Lowry, National Review July 1, 2008

- ↑ Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 86, 162.

- ↑ Religious affiliation of Supreme Court justices Justice Sherman Minton converted to Catholicism after his retirement.

See also

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

External links

- "Unenumerated Rights and the Dictates of Judicial Restraint." Address to the Canadian Institute for Advanced Legal Studies, Stanford University. Palo Alto, California. July 24 - Aug. 1, 1986.

- "Kennedy's Benchmarks" by Mark Trapp, American Spectator (July 14, 2004).

- Transcript of Senate Confirmation Hearing, 1987.

- Supreme Court Research Guide and Bibliography: Anthony M. Kennedy

- Collection of notable statements by Anthony Kennedy.

- Jonah Goldberg, "Justice Kennedy's Mind: Where the Constitution resides," 2005.

- Supreme court official bio (PDF)

- Jeffrey Toobin, "Swing Shift: How Anthony Kennedy’s passion for foreign law could change the Supreme Court," New Yorker (2005).

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Charles Merton Merrill |

Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit 1975-1988 |

Succeeded by Pamela Ann Rymer |

| Preceded by Lewis Franklin Powell, Jr. |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1988-present |

Incumbent |

| Order of precedence in the United States of America | ||

| Preceded by Antonin Scalia Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States |

United States order of precedence Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States |

Succeeded by David Souter Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States |

|

||||||||||||||

| Supreme Court of the United States | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Kennedy, Anthony McLeod |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 23, 1936 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Sacramento, California |

| DATE OF DEATH | |

| PLACE OF DEATH | |