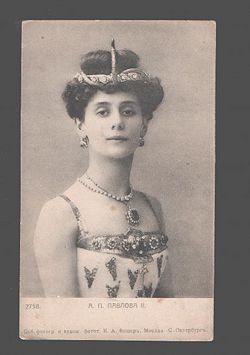

Anna Pavlova

Anna Pavlovna Pavlova (Russian: А́нна Па́вловна Па́влова) (12 February 1881 [O.S. 31 January]–23 January 1931) was a famous Russian ballerina of the late 19th and the early 20th century. Her name along with that of Nijinsky is synonymous with the art of ballet. Pavlova is a legend largely remembered for her famous dance The Dying Swan and because she was the first ballerina to travel around the world and bring ballet to people who had never seen it.

Contents |

Personal Life and Career

Pavlova was born two months premature on 12 February [O.S. 31 January] 1881 in Ligovo, a suburb (now neighborhood) of Saint Petersburg, then the capital of the Russian Empire. Her mother was an impoverished laundress named Lyubov Pavlova. The identity of her father has been open to debate: she later claimed her father (who was of possible Jewish origin)[1] had died when she was two years old. The newspaper The Saint Petersburg Gazette published an article in 1913 claiming that her father was a banker named Poliakov, and that her mother's second husband, Matvey Pavlov, had adopted her at the age of three, by which she acquired her last name

Pavlova's passion for the art of ballet was sparked when her mother took her to a performance of Marius Petipa's original production of The Sleeping Beauty at the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre. The lavish spectacle made a profound impression on the young Pavlova, and at the age of eight her mother took her to audition for the renowned Imperial Ballet School. She was rejected due to her age and for what was considered to be a "sickly" physique, but she was finally accepted at the age of ten in 1891. She made her first appearance in a ballet as a cupid in Petipa's Un conte de fées (A Fairy Tale), which the ballet master staged especially for the students of the school.

Pavlova's years at the Imperial Ballet School were difficult. Ballet technique did not come easily to the young Pavlova. Her extremely arched feet, thin ankles, and long limbs clashed with the small, compact body which was at that time in favor for the ballerina. Her fellow students taunted her with such nicknames as The broom and La petite sauvage. Undeterred, Pavlova trained relentlessly to improve her technique. She took extra lessons from the great teachers of the day—Christian Johansson, Pavel Gerdt and Nikolai Legatand she did ballet on every day of the week. In 1898 she entered the classe de perfection of Ekaterina Vazem, former Prima ballerina of the Saint Petersburg Imperial Theatres.

During her final year at the Imperial Ballet School, she performed many soloist roles with the principal company, performing small roles in many of the grand ballets of the era. She graduated in 1899 at age 18, being allowed to enter the Imperial Ballet a rank ahead of corps de ballet as a coryphée. She made her debut with the Imperial Ballet performing a variation in Pavel Gerdt's Les Dryades prétendues (The False Dryads), set to music taken from Cesare Pugni's score for Jules Perrot's romantic ballet Éoline, ou La Dryade. Her performance garnered praise from the critics, particularly the great critic and historian Nikolai Bezobrazov, who praised the young danseuse for her " ... natural ballon, lingering arabesques, and frail femininity.".

At the height of Petipa's strict academicism, the public was at first somewhat reserved in their reaction to Pavlova's unique style—an unusual combination of an extraordinary dance gift that paid little heed to academic rules: she frequently performed with bent knees, poor turnout, misplaced port de bras and incorrectly placed tours. Such a style in many ways harkened back to the time of the romantic ballet and the great ballerinas of old.

Pavlova performed in various classical variations, pas de deux and pas de trois in such ballets as La Camargo, Le Roi Candaule, Marcobomba and The Sleeping Beauty. Her enthusiasm often led her astray—once during a performance as the river Thames in Petipa's The Pharaoh's Daughter her energetic double pique turns led her to lose her balance, and she ended up landing in the prompter's box. Her weak ankles caused her great difficulty during a performance of the variation of the fairy Candide in Petipa's The Sleeping Beauty, leading the ballerina to revise the fairy's hops en pointe, much to the surprise of the Ballet Master Petipa. She nevertheless tried to imitate the great virtuosas of the day, particularly Pierina Legnani, Prima ballerina assoluta of the Imperial Theatres. Once during class she attempted Legnani's fouettés, causing her teacher Pavel Gerdt to fly into a rage. He exclaimed "Leave acrobatics to others ... it is positively more than I can bear to see the pressure such steps put on your delicate muscles and the severe arch of your foot. I beg you to never again try to imitate those who are physically stronger than you. You must realize that your daintiness and fragility are your greatest assets. You should always do the kind of dancing which brings out your own rare qualities instead of trying to win praise by mere acrobatic tricks."

Pavlova rose through the ranks quickly, and she was a favorite of the old maestro Petipa. She was second soloist in 1902, première danseuse in 1905, and finally prima ballerina in 1906 after a resounding performance in Giselle, for which Petipa revised the ballerina's dances especially for her in 1903 (they are still performed today in this version at the Mariinsky). Petipa would revise many grand pas for the ballerina, as well as supplemental variations (among them, the famous variation to a solo harp danced by the lead ballerina of the famous Paquita Grand Pas Classique, to the music of Riccardo Drigo, which Petipa choregraphed for the ballerina's début in Paquita in 1904). She was much celebrated by the fanatical balletomanes of Tsarist Saint Petersburg. Her legions of fans called themselves the Pavlovatzi.

When the prima ballerina assoluta of the Imperial Theatres Mathilde Kschessinska was with child in 1901, she coached Pavlova in the role of Nikya in La bayadère. Kschessinska, not wanting to be upstaged, was certain Pavlova would fail miserably in the role, as she was considered technically inferior due to her small ankles and lithe legs. Instead audiences became enchanted with Pavlova and her frail, ethereal look, which fit the role perfectly, particularly in the scene The Kingdom of the Shades.

Her feet were extremely rigid, so she strengthened her pointe shoe by adding a piece of hard wood on the soles for support and curving the box of the shoe. At the time, many considered this "cheating", for a ballerina of the era was taught that she, not her shoes, must hold her weight en pointe. In Pavlova's case this was extremely difficult, as the shape of her feet required her to balance her weight on her little toes. Her solution became, over time, the precursor of the modern pointe shoe, as pointe work became less painful and easier for curved feet. According to Margot Fonteyn's biography, Pavlova did not like the way her invention looked in photographs, so she would remove it or have the photographs altered so that it appeared she was using a normal pointe shoe. [2]

In the first years of the Ballets Russes Pavlova worked briefly for Sergei Diaghilev. Originally she was to dance the lead in Mikhail Fokine's The Firebird, but refused the part, as she could not come to terms with Igor Stravinsky's avant-garde score, and the role was given to Tamara Karsavina. All her life Pavlova preferred the melodious "musique dansante" of the old maestros such as Cesare Pugni and Ludwig Minkus, and cared little for anything else which strayed from the salon-style ballet music of the 19th century.

By the mid 1900s she founded her own company and performed throughout the world, with a repertory consisting primarily of abridgements from the Imperial Petipa works, and specially choreographed pieces for herself. The ballet writer Cyril Johnson described that "her bourrées were like a string of pearls".

Her most famous showpiece was The Dying Swan, choreographed for her by Michel Fokine in 1905, danced to Le Cygne from The Carnival of the Animals by Camille Saint-Saëns.

She was married to Victor Dandre (1870 - 1944) who was also her manager and biographer.

Death

While touring in The Hague, Netherlands, Pavlova was in a train which malfunctioned and had a mild derailment. Dressed only in pajamas and a light scarf, she got out and walked the length of the train to see what had happened. Three weeks later she died of pneumonia, three weeks short of her 50th birthday. Reportedly, she said "If I can't dance then I'd rather be dead," and asked to hold her costume from The Dying Swan. While holding her costume she spoke her last words; "Play the last measure very softly." The end for Pavlova came in the Hotel Des Indes in The Hague, which shows a plaque on the wall.

In accordance with old ballet tradition, on the day she was to have next performed, the show went on as scheduled, with a single spotlight circling an empty stage where she would have been. Memorial services were held in the Russian Orthodox Church in London. Anna Pavlova was cremated, and her ashes placed in a columbarium at Golders Green Crematorium, where her urn was subsequently adorned with her ballet shoes. In 2001 there was an attempt to move her remains to the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow in accordance with her requests. After considerable controversy, the request was turned down.[3]

Other points of her legacy

- The Pavlova dessert was named after her.

- Anna Pavlova once said that the country that would produce the best ballerina in history would be the United States because of all the different cultures that came together there.

Notes

- ↑ Lewis, Jone Johnson. "Anna Pavlova". Retrieved on 23 September, 2007.

- ↑ Fonteyn, Margot, Pavlova, Portrait of a Dancer. Viking, 1984.

- ↑ Collett-White, Mike. "Row Escalates Over Anna Pavlova's Ashes". The Saint Petersburg Times, 13 March 2001. Retrieved on 23 September 2007.

External links

- Anna Pavlova in Australia – 1926, 1929 Tours - material held by the National Library of Australia

- Pictures of Anna Pavlova - digitised and held by the National Library of Australia

- Creative Quotations from Anna Pavlova

- Andros on Ballet

- Heroine Worship: Anna Pavlova, The Swan

- Anna Pavlova on Encyclopaedia Britannica