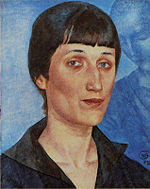

Anna Akhmatova

Anna Akhmatova (Russian: А́нна Ахма́това, real name А́нна Андре́евна Горе́нко) (June 23 [O.S. June 11] 1889 — March 5, 1966) was the pen name of Anna Andreevna Gorenko, a Russian poet credited with a large influence on Russian poetry.

Akhmatova's work ranges from short lyric poems to universalized, ingeniously structured cycles, such as Requiem(1935-40), her tragic masterpiece about the Stalinist terror. Her work addresses a variety of themes including time and memory, the fate of creative women, and the difficulties of living and writing in the shadow of Stalinism.

Contents |

Early life

Akhmatova was born at Bolshoy Fontan in Odessa to Andrey Antonovich Gorenko and Inna Erazmova Stogova. Her childhood does not appear to have been happy; her parents separated in 1905. She was educated in Tsarskoe Selo (where she first met her future husband, Nikolay Gumilyov) and in Kyiv. Anna started writing poetry at the age of 11, inspired by her favourite poets: Racine, Pushkin, and Baratynsky. As her father did not want to see any verses printed under his "respectable" name, she chose to adopt the surname of her Tatar grandmother as a pseudonym.

[1].

Grey-Eyed King (1910)

Hail to thee, o, inconsolate pain!

The young grey-eyed king has been yesterday slain.

That autumnal evening was stuffy and red.

My husband, returning, had quietly said,

"He'd left for his hunting; they carried him home;

They found him under the old oak's dome.

I pity his queen. He, so young, passed away!...

During one night her black hair turned to grey."

He picked up his pipe from the fireplace shelf,

And went off to work for the night by himself.

Now my daughter I will wake up and rise --

And I will look in her little grey eyes...

And murmuring poplars outside can be heard:

Your king is no longer here on this earth. [2]

Many of the male Russian poets of the time declared their love for Akhmatova; she reciprocated the attentions of Osip Mandelstam, whose wife, Nadezhda Mandelstam, would eventually forgive Akhmatova in her autobiography, Hope Against Hope [2]. In 1910, she married the boyish poet, Nikolay Gumilyov, who very soon left her for lion hunting in Africa, the battlefields of World War I, and the society of Parisian grisettes. Her husband did not take her poems seriously, and was shocked when Alexander Blok declared to him that he preferred her poems to his. Their son, Lev, born in 1912, was to become a famous Neo-Eurasianist historian.

Silver Age

In 1912, she published her first collection, entitled Evening. It contained brief, psychologically taut pieces which English readers may find distantly reminiscent of Robert Browning and Thomas Hardy. They were acclaimed for their classical diction, telling details, and the skilful use of colour.

By the time her second collection, the Rosary, appeared in 1914, there were thousands of women composing poems "in honour of Akhmatova." Her early poems usually picture a man and a woman involved in the most poignant, ambiguous moment of their relationship. Such pieces were much imitated and later parodied by Nabokov and others. Akhmatova was prompted to exclaim: "I taught our women how to speak, but don't know how to make them silent".

Together with her husband, Akhmatova enjoyed a high reputation in the circle of Acmeist poets. Her aristocratic manners and artistic integrity won her the titles "Queen of the Neva" and "Soul of the Silver Age," as the period came to be known in the history of Russian poetry. Many decades later, she would recall this blessed time of her life in the longest of her works, "Poem Without a Hero" (1940–65), inspired by Pushkin's Eugene Onegin.

Mosaics in Ireland and England

Following the breakup of her marriage, Akhmatova had an affair with the mosaic artist and poet Boris Anrep (1883 - 1969) during World War I; at least 34 of her poems are about him. He in turn created mosaics in which she features. In the Cathedral of Christ the King Mullingar, Anrep’s mosaic of Saint Anne is spelt Anna. Additionally, the saint’s image bears an uncanny resemblance to that of Akhmatova in her mid-20s.[3]

Anrep also depicted Akhmatova in a mosaic entitled Compassion, located in the National Gallery in London.[4]

The accursed years

Nikolay Gumilyov was executed in 1921 for activities considered anti-Soviet; Akhmatova then married a prominent Assyriologist Vladimir Shilejko, and then an art scholar, Nikolay Punin, who died in the Stalinist Gulag camps.[5] After that, she spurned several proposals from the married poet, Boris Pasternak.

My Way (1940)

One goes in straightforward ways,

One in a circle roams:

Waits for a girl of his gone days,

Or for returning home.

But I do go -- and woe is there --

By a way nor straight, nor broad,

But into never and nowhere,

Like trains -- off the railroad.

After 1922, Akhmatova was condemned as a bourgeois element[2], and from 1925 to 1940, her poetry was banned from publication. She earned her living by translating Leopardi and publishing essays, including some brilliant essays on Pushkin, in scholarly periodicals. All of her friends either emigrated or were repressed.

Only a few people in the West suspected that she was still alive, when she was allowed to publish a collection of new poems in 1940. During World War II, when she witnessed the nightmare of the 900-Day Siege, her patriotic poems found their way to the front pages of Pravda. After Akhmatova returned to Leningrad following the Central Asian evacuation in 1944, she was distressed by "a terrible ghost that pretended to be my city."

Upon learning about Isaiah Berlin's visit to Akhmatova in 1946, Stalin's associate in charge of culture, Andrei Zhdanov, publicly labelled her "half harlot, half nun", had her poems banned from publication, and attempted to have her expelled from the Writers' Union, tantamount to a death sentence by starvation.[2] Her son spent his youth in Stalinist gulags, and she even resorted to publishing several poems in praise of Stalin to secure his release. Their relations remained strained, however.

Although officially stifled, Akhmatova's work continued to circulate in samizdat form and even by word of mouth, as she became a symbol of suppressed Russian heritage[2].

The thaw

After Stalin's death, Akhmatova's preeminence among Russian poets was grudgingly conceded, even by party officials, and a censored edition of her work was published; conspicuously absent was Requiem, which Isaiah Berlin had predicted in 1946 would never be published in the Soviet Union[2]. Her later pieces, composed in neoclassical rhyme and mood, seem to be the voice of many she has outlived. Her dacha in Komarovo was frequented by Joseph Brodsky and other young poets, who continued Akhmatova's traditions of Saint Petersburg poetry into the 21st century.

In honor of her 75th birthday in 1964, special observances were held and new collections of her verse were published.[6]

Akhmatova got a chance to meet some of her pre-revolutionary acquaintances in 1965, when she was allowed to travel to Sicily and England, in order to receive the Taormina prize and an honorary doctoral degree from Oxford University (she was accompanied by her life-long friend and secretary Lydia Chukovskaya). In 1962, her dacha was visited by Robert Frost. In 1968, a two volume collection of Akhmatova's prose and poetry was published by Inter-Language Literary Associates of West Germany[2].

Akhmatova died at the age of 76 in St. Peterburg. She was interred at Komarovo Cemetery.

Song of the Last Meeting (1911)

My breast grew helplessly cold,

But my steps were light.

I pulled the glove from my left hand

Mistakenly onto my right.

It seemed there were so many steps,

But I knew there were only three!

Amidst the maples an autumn whisper

Pleaded: "Die with me!

I'm led astray by evil

Fate, so black and so untrue."

I answered: "I, too, dear one!

I, too, will die with you..."

This is a song of the final meeting.

I glanced at the house's dark frame.

Only bedroom candles burning

With an indifferent yellow flame.

Akhmatova's reputation continued to grow after her death, and it was in the year of her centenary that one of the greatest poetic monuments of the 20th century, Akhmatova's Requiem, was finally published in her homeland.

There is a museum devoted to Akhmatova at the apartment where she lived with Nikolai Punin at the garden wing of the Fountain House (more properly known as the Sheremetev Palace) on the Fontanka Embankment, where Akhmatova lived from the mid 1920s until 1952.

A minor planet 3067 Akhmatova discovered by Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Georgievna Karachkina in 1982 is named after her. [7]

Works

Poetry

- Anna Akhmatova: Poems (1983)

- Anno Domini MCMXXI (1922) - rus

- Evening (1912) - rus

- Plantain (1921) - rus

- Poems of Akhmatova (1967)

- Poems of Akhmatova (1983) (trans. Lyn Coffin)

- Rosary (1914)

- Selected Poems (1976)

- Selected Poems (1989)

- The Complete Poems of Anna Akhmatova (1990)

- Twenty Poems of Anna Akhmatova (1985)

- White Flock (1914)

References

- ↑ Anderson, Nancy K.; Anna Andreevna Akhmatova (2004). The word that causes death's defeat. Yale University Press.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 James, Clive. "Anna Akhmatova Assessed". Clive's Lives. Slate.com.

- ↑ In “Ana Achmatova and Mullingar Connection” - broadcast on RTÉ 4th May 2008, the poet Joseph Woods recounts the story of the mosaics. Relevant section begins at timestamp 40’43”.

- ↑ For English-language commentary on the relationship between Akhmatova and Anrep, please see Wendy Rosslyn, "A propos of Anna Akhmatova: Boris Vasilyevich Anrep (1883 - 1969)," New Zealand Slavonic Journal 1 (1980): 25 - 34.

- ↑ N. N. (Nikolai Nikolaevich) Punin Diaries. [1]

- ↑ Harrison E. Salisbury, "Soviet" section of "Literature" article, page 502, Britannica Book of the Year 1965 (covering events of 1964), published by The Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1965

- ↑ Dictionary of Minor Planet Names - p.253

Bibliography

- Feinstein, Elaine. Anna of all the Russias: A life of Anna Akhmatova. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2005 (ISBN 0-297-64309-6); N.Y.: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006 (ISBN 1-4000-4089-2).

- Poem Without a Hero & Selected Poems, trans. Lenore Mayhew and William McNaughton (Oberlin College Press, 1989), ISBN 0-932440-51-7

- Reeder, Roberta. Anna Akhmatova: Poet and Prophet. New York: Picador, 1994 (ISBN 0-312-13429-0).

External links

- [3] - new translation by Perdika Press

- Russian and English text side by side, translated by Andrey Kneller

- Anna Akhmatova at the Wikilivres

- Akhmatova website with biography, video

- (four translations)

- Anna Akhmatova Bio and Poetry

- The Obverse of Stalinism: Akhmatova's self-serving charisma of selflessness by Alexander Zholkovsky

- Akhmatova: brief biography, Requiem, links

- Son of Akhmatova Lev Gumilev (English, Russian)

- Anna Achmatowa - Works in Russian, German and English at the eLibrary Projekt (eLib)

- English and Russian text of "Requiem," translated by Lyn Coffin