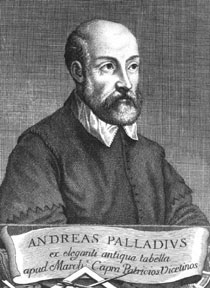

Andrea Palladio

| Andrea Palladio | |

|

|

| Born | November 30, 1508 Padua |

|---|---|

| Died | August 19, 1580 (aged 71) Maser, near Treviso |

| Nationality | Venetian |

| Occupation | Architect |

Andrea Palladio (November 30, 1508 – August 19, 1580), was an Italian architect, widely considered the most influential person in the history of Western architecture.

Contents |

Biography

He was born Andrea di Pietro della Gondola in Padua, then part of the Republic of Venice. Apprenticed as a stonecutter in Padova when he was 13, he broke his contract after only 18 months and fled to the nearby town of Vicenza. Here he became an assistant in the leading workshop of stonecutters and masons. He frequented the workshop of Bartolomeo Cavazza, from whom he learned some of his skills.

His talents were first recognized in his early thirties by Count Gian Giorgio Trissino, who employed the young mason on a building project. It was also Trissino who gave him the name by which he is now known, Palladio, an allusion to the Greek goddess of wisdom Pallas Athene. Palladio later benefited from the patronage of the Barbaro brothers, Daniele Barbaro, who encouraged his studies of classical architecture in Rome, and the younger brother Marcantonio Barbaro. The Palladian style, named after him, adhered to classical Roman principles (Palladio knew relatively little about Greek architecture). His architectural works have "been valued for centuries as the quintessence of High Renaissance calm and harmony" (Watkin, D., A History of Western Architecture). Palladio designed many churches, villas, and palaces, especially in Venice, Vicenza and the surrounding area. A number of his works are protected as part of the World Heritage Site City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto. Other buildings by Palladio are to be found within the Venice and its Lagoon World Heritage Site.

Cultural context

Palladio's architecture was not dependent on expensive materials, which must have been an advantage to his more financially-pressed clients. Many of his buildings are of brick covered with stucco. In the later part of his career, Palladio was chosen by powerful members of Venetian society for numerous important commissions. His success as an architect is based not only on the beauty of his work, but also for its harmony with the culture of his time. His success and influence was a result of the integration of extraordinary aesthetic quality with expressive characteristics that resonated with his client's social aspirations. His buildings served to visually communicate their place in the social order of their culture. This powerful integration of beauty and the physical representation of social meanings is apparent in three major building types: the urban palazzo, the agricultural villa, and the church.

In his urban structures he developed a new improved version of the typical early renaissance palazzo (exemplified by the Palazzo Strozzi). Adapting a new urban palazzo type created by Bramante in the House of Raphael, Palladio found a powerful expression of the importance of the owner and his social position. The main living quarters of the owner on the second level are now clearly distinguished in importance by use of a pedimented classical portico, centered and raised above the subsidiary and utilitarian ground level (illustrated in the Palazzo da Porto Festa and the Palazzo Valmarana Braga). The tallness of the portico is achieved by incorporating the owner's sleeping quarters on the third level, within a giant two story classical colonnade, a motif adapted from Michelangelo's Capitoline buildings in Rome. The elevated main floor level became known as the "piano nobile", and is still referred to as the "first floor" in continental Europe.

Palladio also established an influential new building format for the agricultural villas of the Venetian aristocracy. He consolidated the various stand-alone farm outbuildings into a single impressive structure, arranged as a highly organized whole dominated by a strong center and symmetrical side wings, as illustrated at Villa Barbaro. The Palladian villa configuration often consists of a centralized block raised on an elevated podium, accessed by grand steps and flanked by lower service wings, as at Villa Foscari and Villa Badoer. This format, with the quarters of the owner at the elevated center of their own world, found resonance as a prototype for Italian villas and later for the country estates of the English nobility (such as Lord Burlington's Chiswick House, Vanbrugh's Blenheim, Walpole's Houghton Hall, and Adam's Kedleston Hall). The configuration was a perfect architectural expression of their worldview, clearly expressing their perceived position in the social order of the times. His influence was extended worldwide into the British colonies. The Palladian villa format was easily adapted for a democratic worldview, as can be seen at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello and his arrangement for the University of Virginia; and as recently as 1940 in Pope's National Gallery in Washington DC, where the public entry to the world of high culture occupies the exalted center position. The rustication of exposed basement walls of Victorian residences is a late remnant of the Palladian format, clearly expressed as a podium for the main living space for the family.

Similarly, Palladio created a new configuration for the design of Roman Catholic churches that established two interlocking architectural orders, each clearly articulated yet delineating a hierarchy of a larger order overriding a lesser order. This idea was in direct coincidence with the rising acceptance of the theological ideas of St. Thomas Aquinas, who postulated the notion of two worlds existing simultaneously: the divine world of faith and the earthly world of man. Palladio created an architecture which made a visual statement communicating the idea of two superimposed systems, as illustrated at San Francesco della Vigna. In a time when religious dominance in Western culture was threatened by the rising power of science and secular humanists, this architecture found great favor with the Church as a clear statement of the proper relationship of the earthly and the spiritual worlds.

Palladio died in Maser, near Treviso.

Influence

Palladio's influence was far-reaching, although his buildings are all in a relatively small part of Italy. One factor in the spread of his influence was the publication in 1570 of his architectural treatise I Quattro Libri dell'Architettura (The Four Books of Architecture), which set out rules others could follow. Before this landmark publication, architectural drawings by Palladio had appeared in print as illustrations to Daniele Barbaro's "Commentary" on Vitruvius.[1]

Interest in his style was renewed in later generations and became fashionable all over Europe, for example in parts of the Loire Valley of France. In Britain, Inigo Jones and Christopher Wren embraced the Palladian style. Another admirer was the architect Richard Boyle, 4th Earl of Cork, also known as Lord Burlington, who, with William Kent, designed Chiswick House. Exponents of Palladianism include the 18th century Venetian architect Giacomo Leoni who published an authoritative four-volume work on Palladio and his architectural concepts.

Chronology

- 1508: Born in Padua on 30 November

- 1521: Begins work as a stone mason

- 1540: Begins his first work, Villa Godi in Lonedo

- 1544: Begins construction of Villa Pisani in Bagnolo

- 1545: Involved in the refurbishment of the Basilica of Vicenza

- 1549: Begin construct the Basilica Palladiana

- 1550: Produces drawings for Palazzo Chiericati and Villa Foscari

- 1552: Begins work on Villa Cornaro and the palace of Iseppo De' Porti

- 1554: Begins work on Villa Barbaro in Maser

- 1556: In Udine he works on Casa Antonini and in Vicenza begins with Palazzo Thiene. While his assignments increase along with his fame, he collaborates with Daniele Barbaro on his commentary on Vitruvius, providing the drawings.

- 1557: Begins Villa Badoer in the Po river valley

- 1558: Realises a project for the church of San Pietro di Castello in Venice and probably in the same year begins the construction of Villa Malcontenta

- 1559: Begins Villa Emo in the village of Fanzolo di Vedelago

- 1561: Begins the construction of Villa Pojana and at the same time of the refectory of the Benedictine San Giorgio Monastery, and subsequently the facade of the monastery Monastero per la Carità and the Villa Serego

- 1562: Begins the facade of San Francesco della Vigna and work on San Giorgio Maggiore

- 1565: Begins the construction of Villa Cagollo in Vicenza and Villa Pisani (Montagnana) in Montagnana

- 1566: Palazzo Valmarana and Villa Zeno

- 1567: Begins works for the Villa Capra "La Rotonda"

- 1570: He is nominated Proto della Serenissima (chief architect of the Republic of Venice), and publishes in Venice I Quattro Libri dell'Architettura (The Four Books of Architecture)

- 1571: Realises: Villa Piovene, Palazzo Porto Barbaran, the Loggia del Capitanio and Palazzo Porto Breganze.

- 1574: Publishes the 'Commentari' (commentaries) of Caesar and works on studies for the front of the Basilica di San Petronio in Bologna

- 1577: Begins the construction of the church of Il Redentore

- 1580: Prepares drawings for the interior of the church of S. Lucia in Venice and in the same year on 23 March oversees the beginning of the construction of the Teatro Olimpico but dies on 19 August 1580

References

External links

- Palladio Centre and Museum in Vicenza, Italy (English) (Italian)

- Palladio's Italian Villas website which includes material by the owners of Villa Cornaro.

- Wonders of Vicenza (English) (Italian)

- The Four Books of Architecture (French) (Italian)

- Quincentenary of Andrea Palladio's birth - Celebration Committee Describes a major exhibition touring venues in Italy, the UK and the USA. (English) (Italian)

- Official Website of the 500 Years Exhibition in Vicenza - Italy (2008) (English) (Italian)

"Andrea Palladio". Catholic Encyclopedia. (1913). New York: Robert Appleton Company.

"Andrea Palladio". Catholic Encyclopedia. (1913). New York: Robert Appleton Company.