Amylase

Amylase is an enzyme that breaks starch down into sugar. Amylase is present in human saliva, where it begins the chemical process of digestion. Foods that contain much starch but little sugar, such as rice and potato, taste slightly sweet as they are chewed because amylase turns some of their starch into sugar in the mouth. The pancreas also makes amylase (alpha amylase) to break down dietary starch into di- and trisaccharides which are converted by other enzymes to glucose to supply the body with energy. Plants and some bacteria also produce amylase. As diastase, amylase was the first enzyme to be discovered and isolated (by Anselme Payen in 1833). Specific amylase proteins are designated by different Greek letters. All amylases are glycoside hydrolases and act on α-1,4-glycosidic bonds.

Contents |

Classification

α-Amylase

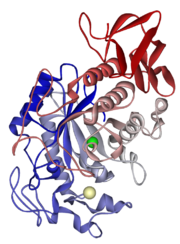

(EC 3.2.1.1 ) (CAS# 9014-71-5) (alternate names: 1,4-α-D-glucan glucanohydrolase; glycogenase) The α-amylases are calcium metalloenzymes, completely unable to function in the absence of calcium. By acting at random locations along the starch chain, α-amylase breaks down long-chain carbohydrates, ultimately yielding maltotriose and maltose from amylose, or maltose, glucose and "limit dextrin" from amylopectin. Because it can act anywhere on the substrate, α-amylase tends to be faster-acting than β-amylase. In animals, it is a major digestive enzyme and its optimum pH is 6.7-7.0. [1]

In human physiology, both the salivary and pancreatic amylases are α-Amylases. They are discussed in much more detail at alpha-Amylase.

Also found in plants (barley) , fungi (ascomycetes and basidiomycetes) and bacteria (Bacillus).

β-Amylase

(EC 3.2.1.2 ) (alternate names: 1,4-α-D-glucan maltohydrolase; glycogenase; saccharogen amylase) Another form of amylase, β-amylase is also synthesized by bacteria, fungi, and plants. Working from the non-reducing end, β-amylase catalyzes the hydrolysis of the second α-1,4 glycosidic bond, cleaving off two glucose units (maltose) at a time. During the ripening of fruit, β-amylase breaks starch into sugar, resulting in the sweet flavor of ripe fruit. Both are present in seeds; β-amylase is present prior to germination, whereas α-amylase and proteases appear once germination has begun. Cereal grain amylase is key to the production of malt. Many microbes also produce amylase to degrade extracellular starches. Animal tissues do not contain β-amylase, although it may be present in microrganisms contained within the digestive tract.

γ-Amylase

(EC 3.2.1.3 ) (alternative names: Glucan 1,4-α-glucosidase; amyloglucosidase; Exo-1,4-α-glucosidase; glucoamylase; lysosomal α-glucosidase; 1,4-α-D-glucan glucohydrolase) In addition to cleaving the last α(1-4)glycosidic linkages at the nonreducing end of amylose and amylopectin, yielding glucose, γ-amylase will cleave α(1-6) glycosidic linkages. Unlike the other forms of amylase, γ-amylase is most efficient in acidic environments and has an optimum pH of 3

Uses

Amylase enzymes are used extensively in bread making to break down complex sugars such as starch (found in flour) into simple sugars. Yeast then feeds on these simple sugars and converts it into the waste products of alcohol and CO2. This imparts flavour and causes the bread to rise. While Amylase enzymes are found naturally in yeast cells, it takes time for the yeast to produce enough of these enzymes to break down significant quantities of starch in the bread. This is the reason for long fermented doughs such as sour dough. Modern bread making techniques have included amylase enzymes (often in the form of malted barley) into bread improver thereby making the bread making process faster and more practical for commercial use.[2]

Bacilliary amylase is also used in detergents to dissolve starches from fabrics.

Workers in factories that work with amylase for any of the above uses are at increased risk of occupational asthma. 5-9% of bakers have a positive skin test, and a fourth to a third of bakers with breathing problems are hypersensitive to amylase. [3]

An inhibitor of alpha-amylase called phaseolamin has been tested as a potential diet aid. [4]

Blood serum amylase may be measured for purposes of medical diagnosis. A normal concentration is in the range 21-101 U/L. A higher than normal concentration may reflect one of several medical conditions, including acute inflammation of the pancreas, macroamylasemia, perforated peptic ulcer, and mumps. Amylase may be measured in other body fluids, including urine and peritoneal fluid.

History

In 1831 Erhard Friedrich Leuchs (1800-1837) described the diastatic action of salivary ptyalin (amylase) on starch.[5] The modern history of enzymes began in 1833 when French chemists described the isolation of an amylase complex from germinating barley and named it diastase.[6] In 1862 Danielewski separated pancreatic amylase from trypsin.[7]

References

- ↑ Effects of pH (Introduction to Enzymes)

- ↑ Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins, Charles William McLaughlin, Susan Johnson, Maryanna Quon Warner, David LaHart, Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- ↑ Mapp CE. Agents, old and new, causing occupational asthma. Occup Environ Med 2001;58:354-60. PMID 11303086.

- ↑ Udani J, Hardy M, Madsen DC. (March 2004). "Blocking carbohydrate absorption and weight loss: a clinical trial using Phase 2 brand proprietary fractionated white bean extract.". Alternative medicine review. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15005645&dopt=Citation.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Anselme Payen and Jean-Franois Persoz (1833). "?". Annales de Chemie et de Physique. http://www.anbio.org.br/english/worksh52.htm.

- ↑ [2]

External links

- Molecule of the month February 2006 at the Protein Data Bank.

- Nutrition Sciences 101 at University of Arizona.

|

||||||||