Americium

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name, Symbol, Number | americium, Am, 95 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | actinides | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group, Period, Block | n/a, 7, f | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery white sometimes yellow | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight | (243) g·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Rn] 5f7 7s2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 25, 8, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 12 g·cm−3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1449 K (1176 °C, 2149 °F) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2880 K (2607 °C, 4725 °F) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 14.39 kJ·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Specific heat capacity | (25 °C) 62.7 J·mol−1·K−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | hexagonal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | 6, 5, 4, 3 (amphoteric oxide) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | 1.3 (Pauling scale) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies | 1st: 578 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | 175 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellaneous | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | no data | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | (300 K) 10 W·m−1·K−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS registry number | 7440-35-9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Most-stable isotopes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| References | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

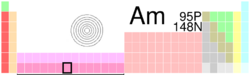

Americium (pronounced /ˌæməˈrɪsiəm/) is a synthetic element that has the symbol Am and atomic number 95. A radioactive metallic element, americium is an actinide that was obtained in 1944 by Glenn T. Seaborg who was bombarding plutonium with neutrons and was the fourth transuranic element to be discovered. It was named for the Americas, by analogy with europium. Americium is widely used in commercial ionization-chamber smoke detectors as well as in neutron sources and industrial gauges.

Contents |

Properties

Pure americium has a silvery and white luster. At room temperatures it slowly tarnishes in dry air. It is more silvery than plutonium or neptunium and apparently more malleable than neptunium or uranium. Alpha emission from 241Am is approximately three times that of radium. Gram quantities of 241Am emit intense gamma rays which creates a serious exposure problem for anyone handling the element.

Americium is also fissile; the critical mass for an unreflected sphere of 241Am is approximately 60 kilograms. It is unlikely that Americium would be used as a weapons material, as its minimum critical mass is considerably larger than that of more readily obtained plutonium or uranium isotopes.[1]

Applications

Americium can be produced in kilogram amounts and has some uses, mostly involving 241Am since it is easiest to produce relatively pure samples of this isotope. Americium is the only synthetic element to have found its way into the household, where one common type of smoke detector contains a tiny amount (about 0.2 microgram) of 241Am as a source of ionizing radiation.[2] This amount emits about 1 microcurie of nuclear radiation when new, with the amount declining slowly as the americium decays into neptunium, a different transuranic element, with a much longer half-life (about 2.14 million years). With its half-life of 432 years, the americium-241 in a smoke detector includes about 5% neptunium after 22 years, and about 10% after 43 years. After the 432-year americium-241 half-life, a smoke detector's original americium would, by definition, be more than half neptunium.

241Am has been used as a portable source of both gamma rays and alpha particles for a number of medical and industrial uses. Gamma ray emissions from 241Am can be used for indirect analysis of materials radiography and for quality control in manufacturing [fixed gauges]. For example, the element has been employed to gauge glass thickness to help create flat glass. 241Am gamma rays were also used to provide passive diagnosis of thyroid function. This medical application is obsolete. 241Am can be combined with lighter elements (e.g., beryllium or lithium) to become a neutron emitter. This application has found uses in neutron radiography as well as a neutron emitting radioactive source. The most widespread use of 241AmBe neutron sources is found in moisture/density gauges used for quality control in highway construction. 241Am neutron sources are also critical for well logging applications. It has also been cited for use as an advanced nuclear rocket propulsion fuel.[3][4] This isotope is, however, extremely expensive to produce in usable quantities.

History

Americium was first isolated by Glenn T. Seaborg, Leon O. Morgan, Ralph A. James, and Albert Ghiorso in late 1944 at the wartime Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago (now known as Argonne National Laboratory). The team created the isotope 241Am by subjecting 239Pu to successive neutron capture reactions in a nuclear reactor. This created 240Pu and then 241Pu which in turn decayed into 241Am via beta decay.[5]

Seaborg was granted a patent for "Element 95 and Method of Producing Said Element," whose unusually terse claim number 1 reads simply, "Element 95."[6] The discovery of americium and curium was first announced informally on a children's quiz show in 1945.[7]

Isotopes

Eighteen radioisotopes of americium have been characterized, with the most stable being 243Am with a half-life of 7370 years, and 241Am with a half-life of 432.2 years. All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives that are less than 51 hours, and the majority of these have half-lives that are less than 100 minutes. This element also has 8 meta states, with the most stable being 242mAm (t½ 141 years). The isotopes of americium range in atomic weight from 231.046 u (231Am) to 249.078 u (249Am).

Chemistry

In aqueous systems the most common oxidation state is +3. It is very much harder to oxidize Am(III) to Am(IV) than it is to oxidise Pu(III) to Pu(IV).

Currently the solvent extraction chemistry of americium is important as in several areas of the world scientists are working on reducing the medium term radiotoxicity of the waste from the reprocessing of used nuclear fuel.

See liquid-liquid extraction for some examples of the solvent extraction of americium.

Americium, unlike uranium, does not readily form a dioxide americyl core (AmO2).[8] This is because americium is very hard to oxidise above the +3 oxidation state when it is in an aqueous solution. In the environment, this americyl core could complex with carbonate as well as other oxygen moieties (OH-, NO2-, NO3-, and SO4-2) to form charged complexes which tend to be readily mobile with low affinities to soil.

- AmO2(OH)+1

- AmO2(OH)2+2

- AmO2CO3+1

- AmO2(CO3)2-1

- AmO2(CO3)3-3

A large amount of work has been done on the solvent extraction of americium, as it is the case that americium and the other transplutonium elements are responsible for the majority of the long lived radiotoxicity of spent nuclear fuel. It is thought that by removal of the americium and curium that the used fuel will only need to be isolated from man and his environment for a shorter time than that required for the isolation of untreated used fuel. One recent EU funded project on this topic was known by the codename "EUROPART". Within this project triazines and other compounds were studied as potential extraction agents.[9][10][11][12][13]

References

- ↑ "Fissile Materials & Nuclear Weapons: Introduction". International Panel on Fissile Materials. Retrieved on 2007-11-22.

- ↑ Americium dioxide is used in smoke detectors. (Internet Archive)

- ↑ "Extremely Efficient Nuclear Fuel Could Take Man To Mars In Just Two Weeks", ScienceDaily (2001-01-03). Retrieved on 2007-11-22.

- ↑ Terry Kammash, David L. Galbraith, and Ta-Rong Jan (January 10, 1993). "An americium-fueled gas core nuclear rocket" in Tenth symposium on space nuclear power and propulsion. AIP Conf. Proc. 271: 585-589. doi:10.1063/1.43073.

- ↑ G. T. Seaborg, R. A. James, L. O. Morgan: "The New Element Americium (Atomic Number 95)", NNES PPR (National Nuclear Energy Series, Plutonium Project Record), Vol. 14 B The Transuranium Elements: Research Papers, Paper No. 22.1, McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc., New York, 1949; Abstract; Typoskript (Januar 1948).

- ↑ Patent US3,156,523 (1964-11-10) Glenn T. Seaborg, Element 95 and Method of Producing Said Element.

- ↑ Rachel Sheremeta Pepling. "It's Elemental: The Periodic Table: Americium". Chemical & Engineering News.

- ↑ David L. Clark (2000). "The Chemical Complexities of Plutonium" (Reprinted at fas.org). Los Alamos Science (26). http://fas.org/sgp/othergov/doe/lanl/pubs/00818038.pdf.

- ↑ Michael J. Hudson, Michael G. B. Drew, Mark R. StJ. Foreman, Clément Hill, Nathalie Huet, Charles Madic and Tristan G. A. Youngs (2003). "The coordination chemistry of 1,2,4-triazinyl bipyridines with lanthanide(III) elements – implications for the partitioning of americium(III)". Dalton Trans.: 1675–1685. doi:.

- ↑ Andreas Geist, Michael Weigl, Udo Müllich, Klaus Gompper (11-13 December 2000). "Actinide(III)/Lanthanide(III) Partitioning Using n-Pr-BTP as Extractant: Extraction Kinetics and Extraction Test in a Hollow Fiber Module" (PDF). 6th Information Exchange Meeting on Actinide and Fission Product Partitioning and Transmutation. OECD Nuclear Energy Agency.

- ↑ C. Hill, D. Guillaneux, X. Hérès, N. Boubals and L. Ramain (24-26 October 2000). "Sanex-BTP Process Development Studies" (PDF). Atalante 2000: Scientific Research on the Back-end of the Fuel Cycle for the 21st Century. Commissariat à l'énergie atomique.

- ↑ Andreas Geist, Michael Weigl and Klaus Gompper (14-16 October 2002). "Effective Actinide(III)-Lanthanide(III) Separation in Miniature Hollow Fibre Modules" (PDF). 7th Information Exchange Meeting on Actinide and Fission Product Partitioning and Transmutation. OECD Nuclear Energy Agency.

- ↑ D.D. Ensor. "Separation Studies of f-Elements" (PDF). Tennessee Tech University.

Further reading

- Nuclides and Isotopes - 14th Edition, GE Nuclear Energy, 1989.

- Gabriele Fioni, Michel Cribier and Frédéric Marie. "Can the minor actinide, americium-241, be transmuted by thermal neutrons?". Commissariat à l'énergie atomique.

- Guide to the Elements - Revised Edition, Albert Stwertka, (Oxford University Press; 1998) ISBN 0-19-508083-1

- Gmelins Handbuch der anorganischen Chemie, System Nr. 71, Band 7 a, Transurane: Teil A 1 I, S. 30–34; Teil A 1 II, S. 18, 315–326, 343–344; Teil A 2, S. 42–44, 164–175, 185–188; Teil B 1, S. 57–67.

External links

- WebElements.com – Americium

- Los Alamos National Laboratory – Americium

- It's Elemental – Americium

- ATSDR – Public Health Statement: Americium

| Periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | He | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cs | Ba | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn | ||||||||||

| Fr | Ra | Ac | Th | Pa | U | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Uub | Uut | Uuq | Uup | Uuh | Uus | Uuo | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![\mathrm{^{239}_{\ 94}Pu\ \xrightarrow {(n,\gamma)} \ ^{240}_{\ 94}Pu\ \xrightarrow {(n,\gamma)} \ ^{241}_{\ 94}Pu\ \xrightarrow [14,35 \ a]{\beta^-} \ ^{241}_{\ 95}Am\ (\ \xrightarrow [432,2 \ a]{\alpha} \ ^{237}_{\ 93}Np)}](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/b137a64da8be96e2a4d876199d5ae97a.png)