Allegory of the cave

|

| Part of a series on Platonism |

| Platonic idealism |

| Platonic realism |

| Middle Platonism |

| Neoplatonism |

| Articles on Neoplatonism |

| Socratic dialogue |

| Socratic method |

| Platonic doctrine of recollection |

| Platonic epistemology |

| Theory of forms |

| Form of the Good |

| Participants in Dialogues |

| Socrates |

| Adeimantus |

| Alcibiades |

| Aristophanes |

| Callicles |

| Glaucon |

| Gorgias |

| Hippias |

| Protagoras |

| Parmenides |

| Theaetetus |

| Thrasymachus |

| Timaeus of Locri |

| Notable Platonists |

| Plotinus |

| Porphyry |

| Iamblichus |

| Proclus |

| Discussions of Plato's works |

| Dialogues of Plato |

| Chariot allegory |

| Allegory of the cave |

| Metaphor of the sun |

| Analogy of the divided line |

| Philosopher king |

| Plato's five regimes |

| Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? |

| The Myth of Er |

| Third Man Argument |

| Demiurge |

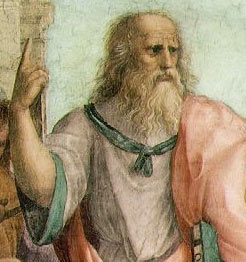

The Allegory of the Cave, also commonly known as Myth of the Cave, Metaphor of the Cave, or the Parable of the Cave, is an allegory used by the Greek philosopher Plato in his work The Republic to illustrate "our nature in its education and want of education." (514a) The allegory of the cave is written as a fictional dialog between Plato's teacher Socrates and Plato's brother Glaucon, at the beginning of Book VII (514a–520a).

Plato imagines a group of people who have lived chained in a cave all of their lives, facing a blank wall. The people watch shadows projected on the wall by things passing in front of the cave entrance, and begin to ascribe forms to these shadows. According to Plato, the shadows are as close as the prisoners get to seeing reality. He then explains how the philosopher is like a prisoner who is freed from the cave and comes to understand that the shadows on the wall are not constitutive of reality at all, as he can perceive the true form of reality rather than the mere shadows seen by the prisoners.

The Allegory is related to Plato's Theory of Forms,[1] wherein Plato asserts that "Forms" (or "Ideas"), and not the material world of change known to us through sensation, possess the highest and most fundamental kind of reality.[2] In addition, the allegory of the cave is an attempt to explain the philosopher's place in society.

The Allegory of the Cave is related to Plato's metaphor of the sun (507b–509c) and the analogy of the divided line (509d–513e), which immediately precede it at the end of Book VI. Allegories are summarized in the viewpoint of dialectic at the end of Book VII and VIII (531d-534e).

Contents |

Presentation

Inside the cave

Socrates begins his presentation by describing a scenario in which what people take to be real would in fact be an illusion. He asks Glaucon to imagine a cave inhabited by prisoners who have been chained and held immobile since childhood: not only are their arms and legs held in place, but their heads are also fixed, compelled to gaze at a wall in front of them. Behind the prisoners is an enormous fire, and between the fire and the prisoners is a raised walkway, along which puppets of various animals, plants, and other things are moved. The puppets cast shadows on the wall, and the prisoners watch these shadows. There are also echoes off the wall from the noise produced from the walkway.

Socrates asks if it isn't reasonable that the prisoners would take the shadows to be real things and the echoes to be real sounds, not just reflections of reality, since they are all they had ever seen? Wouldn't they praise as clever whoever could best guess which shadow would come next, as someone who understood the nature of the world? And wouldn't the whole of their society depend on the shadows on the wall?

Release from the cave

Socrates next introduces something new to this scenario. Suppose that a prisoner is freed and permitted to stand up (Socrates does not specify how). If someone were to show him the things that had cast the shadows, he would not recognize them for what they were and could not name them; he would believe the shadows on the wall to be more real than what he sees.

Suppose further, Socrates says, that the man were compelled to look at the fire: wouldn't he be struck blind and try to turn his gaze back toward the shadows, as toward what he can see clearly and hold to be real? What if someone forcibly dragged such a man upward, out of the cave: wouldn't the man be angry at the one doing this to him? And if dragged all the way out into the sunlight, wouldn't he be distressed and unable to see "even one of the things now said to be true," viz. the shadows on the wall (516a)?

After some time on the surface, however, Socrates suggests that the freed prisoner would acclimate. He would see more and more things around him, until he could look upon the sun. He would understand that the sun is the "source of the seasons and the years, and is the steward of all things in the visible place, and is in a certain way the cause of all those things he and his companions had been seeing" (516b–c). (See also Plato's metaphor of the sun, which occurs near the end of The Republic, Book VI)[3]

Return to the cave

Socrates next asks Glaucon to consider the condition of this man. Wouldn't he remember his first home, what passed for wisdom there, and his fellow prisoners, and consider himself happy and they, pitiable? And wouldn't he disdain whatever honors, praises, and prizes were awarded there to the ones who guessed best which shadows followed which? Moreover, were he to return there, wouldn't he be rather bad at their game, no longer being accustomed to the darkness? "Wouldn't it be said of him that he went up and came back with his eyes corrupted, and that it's not even worth trying to go up? And if they were somehow able to get their hands on and kill the man who attempts to release and lead up, wouldn't they kill him?" (517a)

Remarks on the allegory

Socrates remarks that this allegory can be taken with what was said before, viz. the metaphor of the sun, and the divided line. In particular, he likens

"the region revealed through sight" — the ordinary objects we see around us — "to the prison home, and the light of the fire in it to the power of the sun. And in applying the going up and the seeing of what's above to the soul's journey to the intelligible place, you not mistake my expectation, since you desire to hear it. A god doubtless knows if it happens to be true. At all events, this is the way the phenomena look to me: in the region of the knowable the last thing to be seen, and that with considerable effort, is the idea of good; but once seen, it must be concluded that this is indeed the cause for all things of all that is right and beautiful — in the visible realm it give birth to light and its sovereign; in the intelligible realm, itself sovereign, it provided truth and intelligence — and that the man who is going to act prudently in private or in public must see it" (517b-c).

After "returning from divine contemplations to human evils", a man "is graceless and looks quite ridiculous when — with his sight still dim and before he has gotten sufficiently accustomed to the surrounding darkness — he is compelled in courtrooms or elsewhere to contend about the shadows of justice or the representations of which they are they shadows, and to dispute about the way these things are understood by men who have never seen justice itself?" (517d-e)

References

- ↑ The name of this aspect of Plato's thought is not modern and has not been extracted from certain dialogues by modern scholars. The term was used at least as early as Diogenes Laertius, who called it (Plato's) "Theory of Forms:" Πλάτων ἐν τῇ περὶ τῶν ἰδεῶν ὑπολήψει...., "Plato". Lives of Eminent Philosophers Book III. Paragraph 15.

- ↑ Watt, Stephen (1997), "Introduction: The Theory of Forms (Books 5-7)", Plato: Republic, London: Wordsworth Editions, pp. pages xiv-xvi, ISBN 1853264830

- ↑ Plato, & Jowett, B. (1941). Plato's The Republic. New York: The Modern Library. OCLC: 964319.

External links

- Award winning animated interpretation of Plato's Allegory of the Cave

- Interpreting Plato's Cave

- Video interpretation of the Cave by students at American University on YouTube

- Plato: The Allegory of the Cave, from The Republic at Washington State University

- Plato: The Republic at Project Gutenberg

- Plato: The Allegory of the Cave, from The Republic at University of Washington - Faculty

- Plato: Book VII of The Republic, Allegory of the Cave at Shippensburg University