Algorithm

In mathematics, computing, linguistics and related subjects, an algorithm is a sequence of finite instructions, often used for calculation and data processing. It is formally a type of effective method in which a list of well-defined instructions for completing a task will, when given an initial state, proceed through a well-defined series of successive states, eventually terminating in an end-state. The transition from one state to the next is not necessarily deterministic; some algorithms, known as probabilistic algorithms, incorporate randomness.

A partial formalization of the concept began with attempts to solve the Entscheidungsproblem (the "decision problem") posed by David Hilbert in 1928. Subsequent formalizations were framed as attempts to define "effective calculability" (Kleene 1943:274) or "effective method" (Rosser 1939:225); those formalizations included the Gödel-Herbrand-Kleene recursive functions of 1930, 1934 and 1935, Alonzo Church's lambda calculus of 1936, Emil Post's "Formulation I" of 1936, and Alan Turing's Turing machines of 1936–7 and 1939.

Etymology

Al-Khwārizmī, Persian astronomer and mathematician, wrote a treatise in 825 AD, On Calculation with Hindu Numerals. (See algorism). It was translated into Latin in the 12th century as Algoritmi de numero Indorum (al-Daffa 1977), which title was likely intended to mean "Algoritmi on the numbers of the Indians", where "Algoritmi" was the translator's rendition of the author's name; but people misunderstanding the title treated Algoritmi as a Latin plural and this led to the word "algorithm" (Latin algorismus) coming to mean "calculation method". The intrusive "th" is most likely due to a false cognate with the Greek ἀριθμός (arithmos) meaning "number".

Why algorithms are necessary: an informal definition

No generally accepted formal definition of "algorithm" exists yet.

An informal definition could be "an algorithm is a process that calculates something." For some people, a program is only an algorithm if it stops eventually. For others, a program is only an algorithm if it stops before a given number of calculation steps.

A prototypical example of an "algorithm" is Euclid's algorithm to determine the maximum common divisor of two integers greater than one: "subtract the smaller number from the larger one; repeat until you get a zero or a one." This procedure is known to stop always and the number of subtractions needed is always smaller than the larger of the two numbers.

We can derive clues to the issues involved and an informal meaning of the word from the following quotation from Boolos & Jeffrey (1974, 1999) (boldface added):

No human being can write fast enough or long enough or small enough to list all members of an enumerably infinite set by writing out their names, one after another, in some notation. But humans can do something equally useful, in the case of certain enumerably infinite sets: They can give explicit instructions for determining the nth member of the set, for arbitrary finite n. Such instructions are to be given quite explicitly, in a form in which they could be followed by a computing machine, or by a human who is capable of carrying out only very elementary operations on symbols (Boolos & Jeffrey 1974, 1999, p. 19)

The words "enumerably infinite" mean "countable using integers perhaps extending to infinity." Thus Boolos and Jeffrey are saying that an algorithm implies instructions for a process that "creates" output integers from an arbitrary "input" integer or integers that, in theory, can be chosen from 0 to infinity. Thus we might expect an algorithm to be an algebraic equation such as y = m + n — two arbitrary "input variables" m and n that produce an output y. As we see in Algorithm characterizations — the word algorithm implies much more than this, something on the order of (for our addition example):

- Precise instructions (in language understood by "the computer") for a "fast, efficient, good" process that specifies the "moves" of "the computer" (machine or human, equipped with the necessary internally-contained information and capabilities) to find, decode, and then munch arbitrary input integers/symbols m and n, symbols + and = ... and (reliably, correctly, "effectively") produce, in a "reasonable" time, output-integer y at a specified place and in a specified format.

The concept of algorithm is also used to define the notion of decidability. That notion is central for explaining how formal systems come into being starting from a small set of axioms and rules. In logic, the time that an algorithm requires to complete cannot be measured, as it is not apparently related with our customary physical dimension. From such uncertainties, that characterize ongoing work, stems the unavailability of a definition of algorithm that suits both concrete (in some sense) and abstract usage of the term.

- For a detailed presentation of the various points of view around the definition of "algorithm" see Algorithm characterizations. For examples of simple addition algorithms specified in the detailed manner described in Algorithm characterizations, see Algorithm examples.

Formalization of algorithms

Algorithms are essential to the way computers process information. Many computer programs contain algorithms that specify the specific instructions a computer should perform (in a specific order) to carry out a specified task, such as calculating employees’ paychecks or printing students’ report cards. Thus, an algorithm can be considered to be any sequence of operations that can be simulated by a Turing-complete system. Authors who assert this thesis include Savage (1987) and Gurevich (2000):

...Turing's informal argument in favor of his thesis justifies a stronger thesis: every algorithm can be simulated by a Turing machine (Gurevich 2000:1)...according to Savage [1987], an algorithm is a computational process defined by a Turing machine. (Gurevich 2000:3)

Typically, when an algorithm is associated with processing information, data is read from an input source, written to an output device, and/or stored for further processing. Stored data is regarded as part of the internal state of the entity performing the algorithm. In practice, the state is stored in one or more data structures.

For any such computational process, the algorithm must be rigorously defined: specified in the way it applies in all possible circumstances that could arise. That is, any conditional steps must be systematically dealt with, case-by-case; the criteria for each case must be clear (and computable).

Because an algorithm is a precise list of precise steps, the order of computation will always be critical to the functioning of the algorithm. Instructions are usually assumed to be listed explicitly, and are described as starting "from the top" and going "down to the bottom", an idea that is described more formally by flow of control.

So far, this discussion of the formalization of an algorithm has assumed the premises of imperative programming. This is the most common conception, and it attempts to describe a task in discrete, "mechanical" means. Unique to this conception of formalized algorithms is the assignment operation, setting the value of a variable. It derives from the intuition of "memory" as a scratchpad. There is an example below of such an assignment.

For some alternate conceptions of what constitutes an algorithm see functional programming and logic programming .

Termination

Some writers restrict the definition of algorithm to procedures that eventually finish. In such a category Kleene places the "decision procedure or decision method or algorithm for the question" (Kleene 1952:136). Others, including Kleene, include procedures that could run forever without stopping; such a procedure has been called a "computational method" (Knuth 1997:5) or "calculation procedure or algorithm" (Kleene 1952:137); however, Kleene notes that such a method must eventually exhibit "some object" (Kleene 1952:137).

Minsky makes the pertinent observation, in regards to determining whether an algorithm will eventually terminate (from a particular starting state):

But if the length of the process is not known in advance, then "trying" it may not be decisive, because if the process does go on forever — then at no time will we ever be sure of the answer (Minsky 1967:105).

As it happens, no other method can do any better, as was shown by Alan Turing with his celebrated result on the undecidability of the so-called halting problem. There is no algorithmic procedure for determining of arbitrary algorithms whether or not they terminate from given starting states. The analysis of algorithms for their likelihood of termination is called termination analysis.

See the examples of (im-)"proper" subtraction at partial function for more about what can happen when an algorithm fails for certain of its input numbers — e.g., (i) non-termination, (ii) production of "junk" (output in the wrong format to be considered a number) or no number(s) at all (halt ends the computation with no output), (iii) wrong number(s), or (iv) a combination of these. Kleene proposed that the production of "junk" or failure to produce a number is solved by having the algorithm detect these instances and produce e.g., an error message (he suggested "0"), or preferably, force the algorithm into an endless loop (Kleene 1952:322). Davis does this to his subtraction algorithm — he fixes his algorithm in a second example so that it is proper subtraction (Davis 1958:12-15). Along with the logical outcomes "true" and "false" Kleene also proposes the use of a third logical symbol "u" — undecided (Kleene 1952:326) — thus an algorithm will always produce something when confronted with a "proposition". The problem of wrong answers must be solved with an independent "proof" of the algorithm e.g., using induction:

We normally require auxiliary evidence for this (that the algorithm correctly defines a mu recursive function), e.g., in the form of an inductive proof that, for each argument value, the computation terminates with a unique value (Minsky 1967:186).

Expressing algorithms

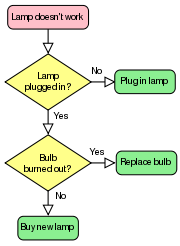

Algorithms can be expressed in many kinds of notation, including natural languages, pseudocode, flowcharts, and programming languages. Natural language expressions of algorithms tend to be verbose and ambiguous, and are rarely used for complex or technical algorithms. Pseudocode and flowcharts are structured ways to express algorithms that avoid many of the ambiguities common in natural language statements, while remaining independent of a particular implementation language. Programming languages are primarily intended for expressing algorithms in a form that can be executed by a computer, but are often used as a way to define or document algorithms.

There is a wide variety of representations possible and one can express a given Turing machine program as a sequence of machine tables (see more at finite state machine and state transition table), as flowcharts (see more at state diagram), or as a form of rudimentary machine code or assembly code called "sets of quadruples" (see more at Turing machine).

Sometimes it is helpful in the description of an algorithm to supplement small "flow charts" (state diagrams) with natural-language and/or arithmetic expressions written inside "block diagrams" to summarize what the "flow charts" are accomplishing.

Representations of algorithms are generally classed into three accepted levels of Turing machine description (Sipser 2006:157):

- 1 High-level description:

-

- "...prose to describe an algorithm, ignoring the implementation details. At this level we do not need to mention how the machine manages its tape or head"

- 2 Implementation description:

-

- "...prose used to define the way the Turing machine uses its head and the way that it stores data on its tape. At this level we do not give details of states or transition function"

- 3 Formal description:

-

- Most detailed, "lowest level", gives the Turing machine's "state table".

- For an example of the simple algorithm "Add m+n" described in all three levels see Algorithm examples.

Implementation

Most algorithms are intended to be implemented as computer programs. However, algorithms are also implemented by other means, such as in a biological neural network (for example, the human brain implementing arithmetic or an insect looking for food), in an electrical circuit, or in a mechanical device.

Example

One of the simplest algorithms is to find the largest number in an (unsorted) list of numbers. The solution necessarily requires looking at every number in the list, but only once at each. From this follows a simple algorithm, which can be stated in a high-level description English prose, as:

High-level description:

- Assume the first item is largest.

- Look at each of the remaining items in the list and if it is larger than the largest item so far, make a note of it.

- The last noted item is the largest in the list when the process is complete.

(Quasi-)formal description: Written in prose but much closer to the high-level language of a computer program, the following is the more formal coding of the algorithm in pseudocode or pidgin code:

Algorithm LargestNumber

Input: A non-empty list of numbers L.

Output: The largest number in the list L.

largest ← L0

for each item in the list L≥1, do

if the item > largest, then

largest ← the item

return largest

- "←" is a loose shorthand for "changes to". For instance, "largest ← item" means that the value of largest changes to the value of item.

- "return" terminates the algorithm and outputs the value that follows.

For a more complex example of an algorithm, see Euclid's algorithm for the greatest common divisor, one of the earliest algorithms known.

Algorithmic analysis

As it happens, it is important to know how much of a particular resource (such as time or storage) is required for a given algorithm. Methods have been developed for the analysis of algorithms to obtain such quantitative answers; for example, the algorithm above has a time requirement of O(n), using the big O notation with n as the length of the list. At all times the algorithm only needs to remember two values: the largest number found so far, and its current position in the input list. Therefore it is said to have a space requirement of O(1), if the space required to store the input numbers is not counted, or O (log n) if it is counted.

Different algorithms may complete the same task with a different set of instructions in less or more time, space, or effort than others. For example, given two different recipes for making potato salad, one may have peel the potato before boil the potato while the other presents the steps in the reverse order, yet they both call for these steps to be repeated for all potatoes and end when the potato salad is ready to be eaten.

The analysis and study of algorithms is a discipline of computer science, and is often practiced abstractly without the use of a specific programming language or implementation. In this sense, algorithm analysis resembles other mathematical disciplines in that it focuses on the underlying properties of the algorithm and not on the specifics of any particular implementation. Usually pseudocode is used for analysis as it is the simplest and most general representation.

Classes

There are various ways to classify algorithms, each with its own merits.

Classification by implementation

One way to classify algorithms is by implementation means.

- Recursion or iteration: A recursive algorithm is one that invokes (makes reference to) itself repeatedly until a certain condition matches, which is a method common to functional programming. Iterative algorithms use repetitive constructs like loops and sometimes additional data structures like stacks to solve the given problems. Some problems are naturally suited for one implementation or the other. For example, towers of hanoi is well understood in recursive implementation. Every recursive version has an equivalent (but possibly more or less complex) iterative version, and vice versa.

- Logical: An algorithm may be viewed as controlled logical deduction. This notion may be expressed as: Algorithm = logic + control (Kowalski 1979). The logic component expresses the axioms that may be used in the computation and the control component determines the way in which deduction is applied to the axioms. This is the basis for the logic programming paradigm. In pure logic programming languages the control component is fixed and algorithms are specified by supplying only the logic component. The appeal of this approach is the elegant semantics: a change in the axioms has a well defined change in the algorithm.

- Serial or parallel or distributed: Algorithms are usually discussed with the assumption that computers execute one instruction of an algorithm at a time. Those computers are sometimes called serial computers. An algorithm designed for such an environment is called a serial algorithm, as opposed to parallel algorithms or distributed algorithms. Parallel algorithms take advantage of computer architectures where several processors can work on a problem at the same time, whereas distributed algorithms utilize multiple machines connected with a network. Parallel or distributed algorithms divide the problem into more symmetrical or asymmetrical subproblems and collect the results back together. The resource consumption in such algorithms is not only processor cycles on each processor but also the communication overhead between the processors. Sorting algorithms can be parallelized efficiently, but their communication overhead is expensive. Iterative algorithms are generally parallelizable. Some problems have no parallel algorithms, and are called inherently serial problems.

- Deterministic or non-deterministic: Deterministic algorithms solve the problem with exact decision at every step of the algorithm whereas non-deterministic algorithm solve problems via guessing although typical guesses are made more accurate through the use of heuristics.

- Exact or approximate: While many algorithms reach an exact solution, approximation algorithms seek an approximation that is close to the true solution. Approximation may use either a deterministic or a random strategy. Such algorithms have practical value for many hard problems.

Classification by design paradigm

Another way of classifying algorithms is by their design methodology or paradigm. There is a certain number of paradigms, each different from the other. Furthermore, each of these categories will include many different types of algorithms. Some commonly found paradigms include:

- Divide and conquer. A divide and conquer algorithm repeatedly reduces an instance of a problem to one or more smaller instances of the same problem (usually recursively), until the instances are small enough to solve easily. One such example of divide and conquer is merge sorting. Sorting can be done on each segment of data after dividing data into segments and sorting of entire data can be obtained in conquer phase by merging them. A simpler variant of divide and conquer is called decrease and conquer algorithm, that solves an identical subproblem and uses the solution of this subproblem to solve the bigger problem. Divide and conquer divides the problem into multiple subproblems and so conquer stage will be more complex than decrease and conquer algorithms. An example of decrease and conquer algorithm is binary search algorithm.

- Dynamic programming. When a problem shows optimal substructure, meaning the optimal solution to a problem can be constructed from optimal solutions to subproblems, and overlapping subproblems, meaning the same subproblems are used to solve many different problem instances, a quicker approach called dynamic programming avoids recomputing solutions that have already been computed. For example, the shortest path to a goal from a vertex in a weighted graph can be found by using the shortest path to the goal from all adjacent vertices. Dynamic programming and memoization go together. The main difference between dynamic programming and divide and conquer is that subproblems are more or less independent in divide and conquer, whereas subproblems overlap in dynamic programming. The difference between dynamic programming and straightforward recursion is in caching or memoization of recursive calls. When subproblems are independent and there is no repetition, memoization does not help; hence dynamic programming is not a solution for all complex problems. By using memoization or maintaining a table of subproblems already solved, dynamic programming reduces the exponential nature of many problems to polynomial complexity.

- The greedy method. A greedy algorithm is similar to a dynamic programming algorithm, but the difference is that solutions to the subproblems do not have to be known at each stage; instead a "greedy" choice can be made of what looks best for the moment. The greedy method extends the solution with the best possible decision (not all feasible decisions) at an algorithmic stage based on the current local optimum and the best decision (not all possible decisions) made in previous stage. It is not exhaustive, and does not give accurate answer to many problems. But when it works, it will be the fastest method. The most popular greedy algorithm is finding the minimal spanning tree as given by Kruskal.

- Linear programming. When solving a problem using linear programming, specific inequalities involving the inputs are found and then an attempt is made to maximize (or minimize) some linear function of the inputs. Many problems (such as the maximum flow for directed graphs) can be stated in a linear programming way, and then be solved by a 'generic' algorithm such as the simplex algorithm. A more complex variant of linear programming is called integer programming, where the solution space is restricted to the integers.

- Reduction. This technique involves solving a difficult problem by transforming it into a better known problem for which we have (hopefully) asymptotically optimal algorithms. The goal is to find a reducing algorithm whose complexity is not dominated by the resulting reduced algorithm's. For example, one selection algorithm for finding the median in an unsorted list involves first sorting the list (the expensive portion) and then pulling out the middle element in the sorted list (the cheap portion). This technique is also known as transform and conquer.

- Search and enumeration. Many problems (such as playing chess) can be modeled as problems on graphs. A graph exploration algorithm specifies rules for moving around a graph and is useful for such problems. This category also includes search algorithms, branch and bound enumeration and backtracking.

- The probabilistic and heuristic paradigm. Algorithms belonging to this class fit the definition of an algorithm more loosely.

- Probabilistic algorithms are those that make some choices randomly (or pseudo-randomly); for some problems, it can in fact be proven that the fastest solutions must involve some randomness.

- Genetic algorithms attempt to find solutions to problems by mimicking biological evolutionary processes, with a cycle of random mutations yielding successive generations of "solutions". Thus, they emulate reproduction and "survival of the fittest". In genetic programming, this approach is extended to algorithms, by regarding the algorithm itself as a "solution" to a problem.

- Heuristic algorithms, whose general purpose is not to find an optimal solution, but an approximate solution where the time or resources are limited. They are not practical to find perfect solutions. An example of this would be local search, tabu search, or simulated annealing algorithms, a class of heuristic probabilistic algorithms that vary the solution of a problem by a random amount. The name "simulated annealing" alludes to the metallurgic term meaning the heating and cooling of metal to achieve freedom from defects. The purpose of the random variance is to find close to globally optimal solutions rather than simply locally optimal ones, the idea being that the random element will be decreased as the algorithm settles down to a solution.

Classification by field of study

- See also: List of algorithms

Every field of science has its own problems and needs efficient algorithms. Related problems in one field are often studied together. Some example classes are search algorithms, sorting algorithms, merge algorithms, numerical algorithms, graph algorithms, string algorithms, computational geometric algorithms, combinatorial algorithms, machine learning, cryptography, data compression algorithms and parsing techniques.

Fields tend to overlap with each other, and algorithm advances in one field may improve those of other, sometimes completely unrelated, fields. For example, dynamic programming was originally invented for optimization of resource consumption in industry, but is now used in solving a broad range of problems in many fields.

Classification by complexity

- See also: Complexity class and Parameterized Complexity

Algorithms can be classified by the amount of time they need to complete compared to their input size. There is a wide variety: some algorithms complete in linear time relative to input size, some do so in an exponential amount of time or even worse, and some never halt. Additionally, some problems may have multiple algorithms of differing complexity, while other problems might have no algorithms or no known efficient algorithms. There are also mappings from some problems to other problems. Owing to this, it was found to be more suitable to classify the problems themselves instead of the algorithms into equivalence classes based on the complexity of the best possible algorithms for them.

Classification by computing power

Another way to classify algorithms is by computing power. This is typically done by considering some collection (class) of algorithms. A recursive class of algorithms is one that includes algorithms for all Turing computable functions. Looking at classes of algorithms allows for the possibility of restricting the available computational resources (time and memory) used in a computation. A subrecursive class of algorithms is one in which not all Turing computable functions can be obtained. For example, the algorithms that run in polynomial time suffice for many important types of computation but do not exhaust all Turing computable functions. The class of algorithms implemented by primitive recursive functions is another subrecursive class.

Burgin (2005, p. 24) uses a generalized definition of algorithms that relaxes the common requirement that the output of the algorithm that computes a function must be determined after a finite number of steps. He defines a super-recursive class of algorithms as "a class of algorithms in which it is possible to compute functions not computable by any Turing machine" (Burgin 2005, p. 107). This is closely related to the study of methods of hypercomputation.

Legal issues

- See also: Software patents for a general overview of the patentability of software, including computer-implemented algorithms.

Algorithms, by themselves, are not usually patentable. In the United States, a claim consisting solely of simple manipulations of abstract concepts, numbers, or signals do not constitute "processes" (USPTO 2006) and hence algorithms are not patentable (as in Gottschalk v. Benson). However, practical applications of algorithms are sometimes patentable. For example, in Diamond v. Diehr, the application of a simple feedback algorithm to aid in the curing of synthetic rubber was deemed patentable. The patenting of software is highly controversial, and there are highly criticized patents involving algorithms, especially data compression algorithms, such as Unisys' LZW patent.

Additionally, some cryptographic algorithms have export restrictions (see export of cryptography).

History: Development of the notion of "algorithm"

Origin of the word

- See also: Timeline of algorithms

The word algorithm comes from the name of the 9th century Persian mathematician Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi whose works introduced Indian numerals and algebraic concepts. He worked in Baghdad at the time when it was the centre of scientific studies and trade. The word algorism originally referred only to the rules of performing arithmetic using Arabic numerals but evolved via European Latin translation of al-Khwarizmi's name into algorithm by the 18th century. The word evolved to include all definite procedures for solving problems or performing tasks.

Discrete and distinguishable symbols

Tally-marks: To keep track of their flocks, their sacks of grain and their money the ancients used tallying: accumulating stones or marks scratched on sticks, or making discrete symbols in clay. Through the Babylonian and Egyptian use of marks and symbols, eventually Roman numerals and the abacus evolved (Dilson, p.16–41). Tally marks appear prominently in unary numeral system arithmetic used in Turing machine and Post-Turing machine computations.

Manipulation of symbols as "place holders" for numbers: algebra

The work of the ancient Greek geometers, Persian mathematician Al-Khwarizmi (often considered the "father of algebra" and from whose name the terms "algorism" and "algorithm" are derived), and Western European mathematicians culminated in Leibniz's notion of the calculus ratiocinator (ca 1680):

- "A good century and a half ahead of his time, Leibniz proposed an algebra of logic, an algebra that would specify the rules for manipulating logical concepts in the manner that ordinary algebra specifies the rules for manipulating numbers" (Davis 2000:1)

Mechanical contrivances with discrete states

The clock: Bolter credits the invention of the weight-driven clock as “The key invention [of Europe in the Middle Ages]", in particular the verge escapement (Bolter 1984:24) that provides us with the tick and tock of a mechanical clock. “The accurate automatic machine” (Bolter 1984:26) led immediately to "mechanical automata" beginning in the thirteenth century and finally to “computational machines" – the difference engine and analytical engines of Charles Babbage and Countess Ada Lovelace (Bolter p.33–34, p.204–206).

Jacquard loom, Hollerith punch cards, telegraphy and telephony — the electromechanical relay: Bell and Newell (1971) indicate that the Jacquard loom (1801), precursor to Hollerith cards (punch cards, 1887), and “telephone switching technologies” were the roots of a tree leading to the development of the first computers (Bell and Newell diagram p. 39, cf Davis 2000). By the mid-1800s the telegraph, the precursor of the telephone, was in use throughout the world, its discrete and distinguishable encoding of letters as “dots and dashes” a common sound. By the late 1800s the ticker tape (ca 1870s) was in use, as was the use of Hollerith cards in the 1890 U.S. census. Then came the Teletype (ca 1910) with its punched-paper use of Baudot code on tape.

Telephone-switching networks of electromechanical relays (invented 1835) was behind the work of George Stibitz (1937), the inventor of the digital adding device. As he worked in Bell Laboratories, he observed the “burdensome’ use of mechanical calculators with gears. "He went home one evening in 1937 intending to test his idea.... When the tinkering was over, Stibitz had constructed a binary adding device". (Valley News, p. 13).

Davis (2000) observes the particular importance of the electromechanical relay (with its two "binary states" open and closed):

- It was only with the development, beginning in the 1930s, of electromechanical calculators using electrical relays, that machines were built having the scope Babbage had envisioned." (Davis, p. 14).

Mathematics during the 1800s up to the mid-1900s

Symbols and rules: In rapid succession the mathematics of George Boole (1847, 1854), Gottlob Frege (1879), and Giuseppe Peano (1888–1889) reduced arithmetic to a sequence of symbols manipulated by rules. Peano's The principles of arithmetic, presented by a new method (1888) was "the first attempt at an axiomatization of mathematics in a symbolic language" (van Heijenoort:81ff).

But Heijenoort gives Frege (1879) this kudos: Frege’s is "perhaps the most important single work ever written in logic. ... in which we see a " 'formula language', that is a lingua characterica, a language written with special symbols, "for pure thought", that is, free from rhetorical embellishments ... constructed from specific symbols that are manipulated according to definite rules" (van Heijenoort:1). The work of Frege was further simplified and amplified by Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell in their Principia Mathematica (1910–1913).

The paradoxes: At the same time a number of disturbing paradoxes appeared in the literature, in particular the Burali-Forti paradox (1897), the Russell paradox (1902–03), and the Richard Paradox (Dixon 1906, cf Kleene 1952:36–40). The resultant considerations led to Kurt Gödel’s paper (1931) — he specifically cites the paradox of the liar — that completely reduces rules of recursion to numbers.

Effective calculability: In an effort to solve the Entscheidungsproblem defined precisely by Hilbert in 1928, mathematicians first set about to define what was meant by an "effective method" or "effective calculation" or "effective calculability" (i.e., a calculation that would succeed). In rapid succession the following appeared: Alonzo Church, Stephen Kleene and J.B. Rosser's λ-calculus, (cf footnote in Alonzo Church 1936a:90, 1936b:110) a finely-honed definition of "general recursion" from the work of Gödel acting on suggestions of Jacques Herbrand (cf Gödel's Princeton lectures of 1934) and subsequent simplifications by Kleene (1935-6:237ff, 1943:255ff). Church's proof (1936:88ff) that the Entscheidungsproblem was unsolvable, Emil Post's definition of effective calculability as a worker mindlessly following a list of instructions to move left or right through a sequence of rooms and while there either mark or erase a paper or observe the paper and make a yes-no decision about the next instruction (cf "Formulation I", Post 1936:289-290). Alan Turing's proof of that the Entscheidungsproblem was unsolvable by use of his "a- [automatic-] machine"(Turing 1936-7:116ff) -- in effect almost identical to Post's "formulation", J. Barkley Rosser's definition of "effective method" in terms of "a machine" (Rosser 1939:226). S. C. Kleene's proposal of a precursor to "Church thesis" that he called "Thesis I" (Kleene 1943:273–274), and a few years later Kleene's renaming his Thesis "Church's Thesis" (Kleene 1952:300, 317) and proposing "Turing's Thesis" (Kleene 1952:376).

Emil Post (1936) and Alan Turing (1936-7, 1939)

Here is a remarkable coincidence of two men not knowing each other but describing a process of men-as-computers working on computations — and they yield virtually identical definitions.

Emil Post (1936) described the actions of a "computer" (human being) as follows:

- "...two concepts are involved: that of a symbol space in which the work leading from problem to answer is to be carried out, and a fixed unalterable set of directions.

His symbol space would be

- "a two way infinite sequence of spaces or boxes... The problem solver or worker is to move and work in this symbol space, being capable of being in, and operating in but one box at a time.... a box is to admit of but two possible conditions, i.e., being empty or unmarked, and having a single mark in it, say a vertical stroke.

- "One box is to be singled out and called the starting point. ...a specific problem is to be given in symbolic form by a finite number of boxes [i.e., INPUT] being marked with a stroke. Likewise the answer [i.e., OUTPUT] is to be given in symbolic form by such a configuration of marked boxes....

- "A set of directions applicable to a general problem sets up a deterministic process when applied to each specific problem. This process will terminate only when it comes to the direction of type (C ) [i.e., STOP]." (U p. 289–290) See more at Post-Turing machine

Alan Turing’s work (1936, 1939:160) preceded that of Stibitz (1937); it is unknown whether Stibitz knew of the work of Turing. Turing’s biographer believed that Turing’s use of a typewriter-like model derived from a youthful interest: “Alan had dreamt of inventing typewriters as a boy; Mrs. Turing had a typewriter; and he could well have begun by asking himself what was meant by calling a typewriter 'mechanical'" (Hodges, p. 96). Given the prevalence of Morse code and telegraphy, ticker tape machines, and Teletypes we might conjecture that all were influences.

Turing — his model of computation is now called a Turing machine — begins, as did Post, with an analysis of a human computer that he whittles down to a simple set of basic motions and "states of mind". But he continues a step further and creates a machine as a model of computation of numbers (Turing 1936-7:116).

- "Computing is normally done by writing certain symbols on paper. We may suppose this paper is divided into squares like a child's arithmetic book....I assume then that the computation is carried out on one-dimensional paper, i.e., on a tape divided into squares. I shall also suppose that the number of symbols which may be printed is finite....

- "The behavior of the computer at any moment is determined by the symbols which he is observing, and his "state of mind" at that moment. We may suppose that there is a bound B to the number of symbols or squares which the computer can observe at one moment. If he wishes to observe more, he must use successive observations. We will also suppose that the number of states of mind which need be taken into account is finite...

- "Let us imagine that the operations performed by the computer to be split up into 'simple operations' which are so elementary that it is not easy to imagine them further divided" (Turing 1936-7:136).

Turing's reduction yields the following:

- "The simple operations must therefore include:

- "(a) Changes of the symbol on one of the observed squares

- "(b) Changes of one of the squares observed to another square within L squares of one of the previously observed squares.

"It may be that some of these change necessarily invoke a change of state of mind. The most general single operation must therefore be taken to be one of the following:

-

- "(A) A possible change (a) of symbol together with a possible change of state of mind.

- "(B) A possible change (b) of observed squares, together with a possible change of state of mind"

- "We may now construct a machine to do the work of this computer." (Turing 1936-7:136)

A few years later, Turing expanded his analysis (thesis, definition) with this forceful expression of it:

- "A function is said to be "effectively calculable" if its values can be found by some purely mechanical process. Although it is fairly easy to get an intuitive grasp of this idea, it is neverthessless desirable to have some more definite, mathematical expressible definition . . . [he discusses the history of the definition pretty much as presented above with respect to Gödel, Herbrand, Kleene, Church, Turing and Post] . . . We may take this statement literally, understanding by a purely mechanical process one which could be carried out by a machine. It is possible to give a mathematical description, in a certain normal form, of the structures of these machines. The development of these ideas leads to the author's definition of a computable function, and to an identification of computability † with effective calculability . . . .

- "† We shall use the expression "computable function" to mean a function calculable by a machine, and we let "effectively calculabile" refer to the intuitive idea without particular identification with any one of these definitions."(Turing 1939:160)

J. B. Rosser (1939) and S. C. Kleene (1943)

J. Barkley Rosser boldly defined an ‘effective [mathematical] method’ in the following manner (boldface added):

- "'Effective method' is used here in the rather special sense of a method each step of which is precisely determined and which is certain to produce the answer in a finite number of steps. With this special meaning, three different precise definitions have been given to date. [his footnote #5; see discussion immediately below]. The simplest of these to state (due to Post and Turing) says essentially that an effective method of solving certain sets of problems exists if one can build a machine which will then solve any problem of the set with no human intervention beyond inserting the question and (later) reading the answer. All three definitions are equivalent, so it doesn't matter which one is used. Moreover, the fact that all three are equivalent is a very strong argument for the correctness of any one." (Rosser 1939:225–6)

Rosser's footnote #5 references the work of (1) Church and Kleene and their definition of λ-definability, in particular Church's use of it in his An Unsolvable Problem of Elementary Number Theory (1936); (2) Herbrand and Gödel and their use of recursion in particular Gödel's use in his famous paper On Formally Undecidable Propositions of Principia Mathematica and Related Systems I (1931); and (3) Post (1936) and Turing (1936-7) in their mechanism-models of computation.

Stephen C. Kleene defined as his now-famous "Thesis I" known as the Church-Turing thesis. But he did this in the following context (boldface in original):

- "12. Algorithmic theories... In setting up a complete algorithmic theory, what we do is to describe a procedure, performable for each set of values of the independent variables, which procedure necessarily terminates and in such manner that from the outcome we can read a definite answer, "yes" or "no," to the question, "is the predicate value true?”" (Kleene 1943:273)

History after 1950

A number of efforts have been directed toward further refinement of the definition of "algorithm", and activity is on-going because of issues surrounding, in particular, foundations of mathematics (especially the Church-Turing Thesis) and philosophy of mind (especially arguments around artificial intelligence). For more, see Algorithm characterizations.

- Abstract machine

- Algorithm characterizations

- Algorithm design

- Algorithmic efficiency (describes ways of estimating, measuring and improving an algorithms speed)

- Algorithm engineering

- Algorithm examples

- Algorithmic music

- Algorithmic trading

- Computability theory (computer science)

- Computational complexity theory

- Data structure

- Heuristics

- Introduction to Algorithms

- Important algorithm-related publications

- List of algorithms

- List of algorithm general topics

- List of terms relating to algorithms and data structures

- Partial function

- Parameterized Complexity

- Performance analysis measuring the actual performance of an algorithm

- Run-time analysis (non-intuitive) estimation of run times, not analysis at run-time! (see Performance analysis above

- Theory of computation

References

- Axt, P. (1959) On a Subrecursive Hierarchy and Primitive Recursive Degrees, Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 92, pp. 85-105

- Blass, Andreas; Gurevich, Yuri (2003), "Algorithms: A Quest for Absolute Definitions", Bulletin of European Association for Theoretical Computer Science 81, http://research.microsoft.com/~gurevich/Opera/164.pdf. Includes an excellent bibliography of 56 references.

- Boolos, George; Jeffrey, Richard (1974, 1980, 1989, 1999), Computability and Logic (4th ed.), Cambridge University Press, London, ISBN 0-521-20402-X: cf. Chapter 3 Turing machines where they discuss "certain enumerable sets not effectively (mechanically) enumerable".

- Burgin, M. Super-recursive algorithms, Monographs in computer science, Springer, 2005. ISBN 0387955690

- Campagnolo, M.L., Moore, C., and Costa, J.F. (2000) An analog characterization of the subrecursive functions. In Proc. of the 4th Conference on Real Numbers and Computers, Odense University, pp. 91-109

- Church, Alonzo (1936a). "An Unsolvable Problem of Elementary Number Theory". The American Journal of Mathematics 58: 345–363. doi:. Reprinted in The Undecidable, p. 89ff. The first expression of "Church's Thesis". See in particular page 100 (The Undecidable) where he defines the notion of "effective calculability" in terms of "an algorithm", and he uses the word "terminates", etc.

- Church, Alonzo (1936b). "A Note on the Entscheidungsproblem". Journal of Symbolic Logic 1 no. 1 and volume 1 no. 3. Reprinted in The Undecidable, p. 110ff. Church shows that the Entscheidungsproblem is unsolvable in about 3 pages of text and 3 pages of footnotes.

- Daffa', Ali Abdullah al- (1977). The Muslim contribution to mathematics. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-85664-464-1.

- Davis, Martin (1965). The Undecidable: Basic Papers On Undecidable Propositions, Unsolvable Problems and Computable Functions. New York: Raven Press. Davis gives commentary before each article. Papers of Gödel, Alonzo Church, Turing, Rosser, Kleene, and Emil Post are included; those cited in the article are listed here by author's name.

- Davis, Martin (2000). Engines of Logic: Mathematicians and the Origin of the Computer. New York: W. W. Nortion. Davis offers concise biographies of Leibniz, Boole, Frege, Cantor, Hilbert, Gödel and Turing with von Neumann as the show-stealing villain. Very brief bios of Joseph-Marie Jacquard, Babbage, Ada Lovelace, Claude Shannon, Howard Aiken, etc.

- This article incorporates text from the NIST Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures, which, as a U.S. government publication, is in the public domain. Source: algorithm.

- Dennett, Daniel (1995). Darwin's Dangerous Idea. New York: Touchstone/Simon & Schuster.

- Yuri Gurevich, Sequential Abstract State Machines Capture Sequential Algorithms, ACM Transactions on Computational Logic, Vol 1, no 1 (July 2000), pages 77–111. Includes bibliography of 33 sources.

- Kleene C., Stephen (1936). "General Recursive Functions of Natural Numbers". Mathematische Annalen Band 112, Heft 5: 727–742. doi:. Presented to the American Mathematical Society, September 1935. Reprinted in The Undecidable, p. 237ff. Kleene's definition of "general recursion" (known now as mu-recursion) was used by Church in his 1935 paper An Unsolvable Problem of Elementary Number Theory that proved the "decision problem" to be "undecidable" (i.e., a negative result).

- Kleene C., Stephen (1943). "Recursive Predicates and Quantifiers". American Mathematical Society Transactions Volume 54, No. 1: 41–73. doi:. Reprinted in The Undecidable, p. 255ff. Kleene refined his definition of "general recursion" and proceeded in his chapter "12. Algorithmic theories" to posit "Thesis I" (p. 274); he would later repeat this thesis (in Kleene 1952:300) and name it "Church's Thesis"(Kleene 1952:317) (i.e., the Church Thesis).

- Kleene, Stephen C. (First Edition 1952). Introduction to Metamathematics (Tenth Edition 1991 ed.). North-Holland Publishing Company. Excellent — accessible, readable — reference source for mathematical "foundations".

- Knuth, Donald (1997). Fundamental Algorithms, Third Edition. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0201896834.

- Kosovsky, N. K. Elements of Mathematical Logic and its Application to the theory of Subrecursive Algorithms, LSU Publ., Leningrad, 1981

- Kowalski, Robert (1979). "Algorithm=Logic+Control". Communications of the ACM (ACM Press) 22 (7): 424–436. doi:. ISSN 0001-0782.

- A. A. Markov (1954) Theory of algorithms. [Translated by Jacques J. Schorr-Kon and PST staff] Imprint Moscow, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1954 [i.e., Jerusalem, Israel Program for Scientific Translations, 1961; available from the Office of Technical Services, U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Washington] Description 444 p. 28 cm. Added t.p. in Russian Translation of Works of the Mathematical Institute, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, v. 42. Original title: Teoriya algerifmov. [QA248.M2943 Dartmouth College library. U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Office of Technical Services, number OTS 60-51085.]

- Minsky, Marvin (1967). Computation: Finite and Infinite Machines (First ed.). Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Minsky expands his "...idea of an algorithm — an effective procedure..." in chapter 5.1 Computability, Effective Procedues and Algorithms. Infinite machines."

- Post, Emil (1936). "Finite Combinatory Processes, Formulation I". The Journal of Symbolic Logic 1: pp.103–105. doi:. Reprinted in The Undecidable, p. 289ff. Post defines a simple algorithmic-like process of a man writing marks or erasing marks and going from box to box and eventually halting, as he follows a list of simple instructions. This is cited by Kleene as one source of his "Thesis I", the so-called Church-Turing thesis.

- Rosser, J.B. (1939). "An Informal Exposition of Proofs of Godel's Theorem and Church's Theorem". Journal of Symbolic Logic 4. Reprinted in The Undecidable, p. 223ff. Herein is Rosser's famous definition of "effective method": "...a method each step of which is precisely predetermined and which is certain to produce the answer in a finite number of steps... a machine which will then solve any problem of the set with no human intervention beyond inserting the question and (later) reading the answer" (p. 225–226, The Undecidable)

- Sipser, Michael (2006). Introduction to the Theory of Computation. PWS Publishing Company.

- Stone, Harold S.. Introduction to Computer Organization and Data Structures (1972 ed.). McGraw-Hill, New York. Cf in particular the first chapter titled: Algorithms, Turing Machines, and Programs. His succinct informal definition: "...any sequence of instructions that can be obeyed by a robot, is called an algorithm" (p. 4).

- Turing, Alan M. (1936-7). "On Computable Numbers, With An Application to the Entscheidungsproblem". Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society series 2, volume 42: 230–265. doi:.. Corrections, ibid, vol. 43(1937) pp.544-546. Reprinted in The Undecidable, p. 116ff. Turing's famous paper completed as a Master's dissertation while at King's College Cambridge UK.

- Turing, Alan M. (1939). "Systems of Logic Based on Ordinals". Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society series 2, volume 45: 161–228. doi:. Reprinted in The Undecidable, p. 155ff. Turing's paper that defined "the oracle" was his PhD thesis while at Princeton USA.

- United States Patent and Trademark Office (2006), 2106.02 **>Mathematical Algorithms< - 2100 Patentability, Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP). Latest revision August 2006

Secondary references

- Bolter, David J.. Turing's Man: Western Culture in the Computer Age ((1984) ed.). The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill NC., ISBN 0-8078-4108-0 pbk.

- Dilson, Jesse. The Abacus ((1968,1994) ed.). St. Martin's Press, NY., ISBN 0-312-10409-X (pbk.)

- van Heijenoort, Jean. From Frege to Gödel, A Source Book in Mathematical Logic, 1879–1931 ((1967) ed.). Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA., 3rd edition 1976[?], ISBN 0-674-32449-8 (pbk.)

- Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma ((1983) ed.). Simon and Schuster, New York., ISBN 0-671-49207-1. Cf Chapter "The Spirit of Truth" for a history leading to, and a discussion of, his proof.

External links

- Eric W. Weisstein, Algorithm at MathWorld.

- Algorithms in Everyday Mathematics

- Algorithms at the Open Directory Project

- Sortier- und Suchalgorithmen (German)