Alfred the Great

| Alfred the Great | |

|---|---|

| King of the Anglo-Saxons | |

|

|

| Statue of Alfred the Great, Winchester | |

| Reign | 23 April 871 – 26 October 899 |

| Predecessor | Æthelred of Wessex |

| Successor | Edward the Elder |

| Spouse | Ealhswith |

| Issue | Ælfthryth Ethelfleda Ethelgiva Edward the Elder Æthelwærd |

| Full name | Ælfrēd of Wessex |

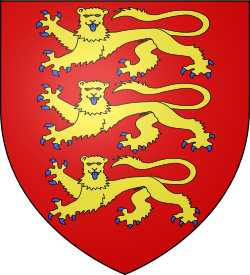

| Royal house | House of Wessex |

| Father | Æthelwulf of Wessex |

| Mother | Osburga |

| Born | c. 849 Wantage, Berkshire |

| Died | 26 October 901 (around 50) |

| Burial | c. 1100 Winchester, Hampshire, now lost. |

Alfred the Great (Old English: Ælfrēd; c. 849 – October 26, c. 899), also spelt Ælfred, was king of the southern Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex from 871 to 899. Alfred is noted for his defence of the kingdom against the Danish Vikings, becoming the only English King to be awarded the epithet "the Great".[1] Alfred was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself "King of the English". Details of his life are discussed in a work by the Welsh scholar Asser. Alfred was a learned man, and encouraged education and improved his kingdom's law system as well as its military structure.

Contents |

Childhood

- Further information: House of Wessex family tree

Alfred was born sometime between 847 and 849 at Wantage in the present-day ceremonial county of Oxfordshire (in the historic county of Berkshire). He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf of Wessex, by his first wife, Osburga.[2] In 868 Alfred married Ealhswith, daughter of Ethelred Mucil.[3]

At five years old, Alfred is said to have been sent to Rome where, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, he was confirmed by Pope Leo IV who "anointed him as king." Victorian writers interpreted this as an anticipatory coronation in preparation for his ultimate succession to the throne of Wessex. However, this coronation could not have been foreseen at the time, since Alfred had three living older brothers. A letter of Leo IV shows that Alfred was made a "consul" and a misinterpretation of this investiture, deliberate or accidental, could explain later confusion.[4] It may also be based on Alfred later having accompanied his father on a pilgrimage to Rome and spending some time at the court of Charles the Bald, King of the Franks, around 854–855. On their return from Rome in 856, Æthelwulf was deposed by his son Æthelbald. Æthelwulf died in 858, and Wessex was ruled by three of Alfred's brothers in succession.

Asser tells the story about how as a child Alfred won a prize of a volume of poetry in English, offered by his mother to the first of her children able to memorise it. This story may be true, or it may be a legend designed to illustrate the young Alfred's love of learning.

Under Ethelred

During the short reigns of his two oldest brothers, Ethelbald and Ethelbert, Alfred is not mentioned. However with the accession of the third brother, Ethelred, in 866, the public life of Alfred began. It is during this period that Asser applies to him the unique title of "secundarius", which may indicate a position akin to that of the Celtic tanist, a recognised successor closely associated with the reigning monarch. It is possible that this arrangement was sanctioned by the Witenagemot, to guard against the danger of a disputed succession should Ethelred fall in battle. The arrangement of crowning a successor as Royal prince and military commander is well-known among Germanic tribes, such as the Swedes and Franks, with whom the Anglo-Saxons had close ties.

In 868, Alfred is recorded fighting beside his brother Ethelred, in an unsuccessful attempt to keep the invading Danes out of the adjoining Kingdom of Mercia. For nearly two years, Wessex was spared attacks because Alfred paid the Vikings to leave him alone. However, at the end of 870, the Danes arrived in his homeland. The year that followed has been called "Alfred's year of battles". Nine martial engagements were fought with varying fortunes, though the place and date of two of the battles have not been recorded. In Berkshire, a successful skirmish at the Battle of Englefield, on 31 December 870, was followed by a severe defeat at the Siege and Battle of Reading, on 5 January 871, and then, four days later, a brilliant victory at the Battle of Ashdown on the Berkshire Downs, possibly near Compton or Aldworth. Alfred is particularly credited with the success of this latter conflict. However, later that month, on 22 January, the English were again defeated at Basing and, on the following 22 March at the Battle of Merton (perhaps Marden in Wiltshire or Martin in Dorset) in which Ethelred was killed. The two unidentified battles may also have occurred in between.

King at war

In April 871, King Ethelred died, and Alfred succeeded to the throne of Wessex and the burden of its defence, despite the fact that Ethelred left two young sons. Although contemporary turmoil meant the accession of Alfred—an adult with military experience and patronage resources—over his nephews went unchallenged, he remained obliged to secure their property rights. While he was busy with the burial ceremonies for his brother, the Danes defeated the English in his absence at an unnamed spot, and then again in his presence at Wilton in May. Following this, peace was made and, for the next five years, the Danes occupied other parts of England. However, in 876, under their new leader, Guthrum, the Danes slipped past the English army and attacked Wareham in Dorset. From there, early in 877, and under the pretext of talks, they moved westwards and took Exeter in Devon. There, Alfred blockaded them, and with a relief fleet having been scattered by a storm, the Danes were forced to submit. They withdrew to Mercia but, in January 878, made a sudden attack on Chippenham, a royal stronghold in which Alfred had been staying over Christmas, "and most of the people they reduced, except the King Alfred, and he with a little band made his way by wood and swamp, and after Easter he made a fort at Athelney, and from that fort kept fighting against the foe" (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle).

A popular legend originating from early twelfth century chronicles,[5] tells how when he first fled to the Somerset Levels, Alfred was given shelter by a peasant woman who, unaware of his identity, left him to watch some cakes she had left cooking on the fire. Preoccupied with the problems of his kingdom, Alfred accidentally let the cakes burn and was taken to task by the woman upon her return. Upon realising the king's identity, the woman apologised profusely, but Alfred insisted that he was the one who needed to apologise. From his fort at Athelney, a marshy island near North Petherton, Alfred was able to mount an effective resistance movement while rallying the local militia from Somerset, Wiltshire and Hampshire.

Another story relates how Alfred disguised himself as a minstrel in order to gain entry to Guthrum's camp and discover his plans. This supposedly led to the Battle of Edington, near Westbury, Wiltshire. The result was a decisive victory for Alfred. The Danes submitted and, according to Asser, Guthrum and 29 of his chief men received baptism when they signed the Treaty of Wedmore. As a result, England became split in two: the southwestern half was kept by the Saxons, and the northeastern half including London, thence known as the Danelaw, was kept by the Vikings. By the following year (879), both Wessex and Mercia, west of Watling Street, were cleared of the invaders.

For the next few years there was peace, with the Danes being kept busy in Europe. A landing in Kent in 884 or 885 close to Plucks Gutter, though successfully repelled, encouraged the East Anglian Danes to rise up. The measures taken by Alfred to repress this uprising culminated in the taking of London in 885 or 886, and an agreement was reached between Alfred and Guthrum, known as the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum. Once more, for a time, there was a lull, but in the autumn of 892 or 893, the Danes attacked again. Finding their position in Europe somewhat precarious, they crossed to England in 330 ships in two divisions. They entrenched themselves, the larger body at Appledore, Kent, and the lesser, under Haesten, at Milton also in Kent. The invaders brought their wives and children with them, indicating a meaningful attempt at conquest and colonisation. Alfred, in 893 or 894, took up a position from whence he could observe both forces. While he was in talks with Haesten, the Danes at Appledore broke out and struck northwestwards. They were overtaken by Alfred's oldest son, Edward, and were defeated in a general engagement at Farnham in Surrey. They were obliged to take refuge on an island in the Hertfordshire Colne, where they were blockaded and were ultimately compelled to submit. The force fell back on Essex and, after suffering another defeat at Benfleet, coalesced with Haesten's force at Shoebury.

Alfred had been on his way to relieve his son at Thorney when he heard that the Northumbrian and East Anglian Danes were besieging Exeter and an unnamed stronghold on the North Devon shore. Alfred at once hurried westward and raised the Siege of Exeter. The fate of the other place is not recorded. Meanwhile the force under Haesten set out to march up the Thames Valley, possibly with the idea of assisting their friends in the west. But they were met by a large force under the three great ealdormen of Mercia, Wiltshire and Somerset, and made to head off to the northwest, being finally overtaken and blockaded at Buttington. Some identify this with Buttington Tump at the mouth of the River Wye, others with Buttington near Welshpool. An attempt to break through the English lines was defeated. Those who escaped retreated to Shoebury. Then after collecting reinforcements they made a sudden dash across England and occupied the ruined Roman walls of Chester. The English did not attempt a winter blockade but contented themselves with destroying all the supplies in the neighbourhood. Early in 894 (or 895), want of food obliged the Danes to retire once more to Essex. At the end of this year and early in 895 (or 896), the Danes drew their ships up the Thames and Lea and fortified themselves twenty miles (32 km) north of London. A direct attack on the Danish lines failed, but later in the year, Alfred saw a means of obstructing the river so as to prevent the egress of the Danish ships. The Danes realised that they were out-manoeuvred. They struck off northwestwards and wintered at Bridgenorth. The next year, 896 (or 897), they gave up the struggle. Some retired to Northumbria, some to East Anglia. Those who had no connections in England withdrew back to Europe.

Reorganisation

After the dispersal of the Danish invaders, Alfred turned his attention to the increase of the navy, partly to repress the ravages of the Northumbrian and East Anglian Danes on the coasts of Wessex, and to prevent the landing of fresh invaders. This is not, as often asserted, the beginning of the English navy. There had been earlier naval operations under Alfred. One naval engagement was fought in the reign of Æthelwulf in 851 by Alfred's brother, Athelstan, and earlier ones, possibly in 833 and 840. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, however, does credit Alfred with the construction of a new type of ship, built according to the king's own designs, "swifter, steadier and also higher/more responsive (hierran) than the others". However, these new ships do not seem to have been a great success, as we hear of them grounding in action and foundering in a storm. Nevertheless both the British Royal Navy and the United States Navy claim Alfred as the founder of their traditions.

Alfred's main fighting force, the fyrd, was separated into two, "so that there was always half at home and half out" (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle). The level of organisation required to mobilise his large army in two shifts, of which one was feeding the other, must have been considerable. The complexity which Alfred's administration had attained by 892 is demonstrated by a reasonably reliable charter whose witness list includes a thesaurius, cellararius and pincerna—treasurer, food-keeper and butler. Despite the irritation which Alfred must have felt in 893, when one division, which had "completed their call-up (stemn)", gave up the siege of a Danish army just as Alfred was moving to relieve them, this system seems to have worked remarkably well on the whole.

One of the weaknesses of pre-Alfredian defences had been that, in the absence of a standing army, fortresses were largely left unoccupied, making it very possible for a Viking force to quickly secure a strong strategic position. Alfred substantially upgraded the state of the defences of Wessex, by erecting a net of fortified burhs (or boroughs) throughout the kingdom that were also planned as centres of habitation and trade. No area of Wessex would be at more than 20 miles of one of these burhs. During the systematic excavation of at least four of these burhs (at Wareham, Cricklade, Lydford and Wallingford), it has been demonstrated that "in every case the rampart associated by the excavators with the borough of the Alfredian period was the primary defence on the site" (Brooks). The obligations for the upkeep and defence of these and many other sites, with permanent garrisons, are further documented in surviving transcripts of the administrative manuscript known as the Burghal Hidage. Dating from, at least, within twenty years of Alfred's death, if not actually from his reign, it almost certainly reflects Alfredian policy. Comparison of town plans for Wallingford and Wareham with that of Winchester, shows "that they were laid out in the same scheme" (Wormald), thus supporting the proposition that these newly established burhs were also planned as centres of habitation and trade as well as a place of safety in moments of immediate danger. Thereafter, the English population and its wealth were drawn into such towns where it was not only safer from Viking soldiers, but also taxable by the King.

Alfred is thus credited with a significant degree of civil reorganisation, especially in the districts ravaged by the Danes. Even if one rejects the thesis crediting the "Burghal Hidage" to Alfred, what is undeniable is that, in the parts of Mercia acquired by Alfred from the Vikings, the shire system seems now to have been introduced for the first time. This is probably what prompted the legend that Alfred was the inventor of shires, hundreds and tithings. Alfred's care for the administration of justice is testified both by history and legend; and he has gained the popular title "protector of the poor". Of the actions of the Witangemot, we do not hear very much under Alfred. He was certainly anxious to respect its rights, but both the circumstances of the time and the character of the king would have tended to throw more power into his hands. The legislation of Alfred probably belongs to the later part of the reign, after the pressure of the Danes had relaxed. He also paid attention to the country's finances, though details are lacking.

Legal reform

Alfred the Great’s most enduring work was his legal code, called Deemings, or Book of Dooms (Book of Laws). Sir Winston Churchill believed that Alfred blended the Mosaic Law, Celtic Law, and old customs of the pagan Anglo-Saxons.[6] Dr. F.N. Lee traced the parallels between Alfred’s Code and the Mosaic Code.[7] However, as Thomas Jefferson concluded after tracing the history of English common law: "The common law existed while the Anglo-Saxons were yet pagans, at a time when they had never yet heard the name of Christ pronounced or that such a character existed".[8] Churchill stated that Alfred’s Code was amplified by his successors and grew into the body of Customary Law administered by the Shire and The Hundred Courts. This led to the Charter of Liberties, granted by Henry I of England, AD 1100.

Foreign relations

Asser speaks grandiosely of Alfred's relations with foreign powers, but little definite information is available. His interest in foreign countries is shown by the insertions which he made in his translation of Orosius. He certainly corresponded with Elias III, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, and possibly sent a mission to India. Contact was also made with the Caliph in Baghdad. Embassies to Rome conveying the English alms to the Pope were fairly frequent. Around 890, Wulfstan of Haithabu undertook a journey from Haithabu on Jutland along the Baltic Sea to the Prussian trading town of Truso. Alfred ensured he reported to him details of his trip.

Alfred's relations with the Celtic princes in the western half of Britain are clearer. Comparatively early in his reign, according to Asser, the southern Welsh princes, owing to the pressure on them of North Wales and Mercia, commended themselves to Alfred. Later in the reign the North Welsh followed their example, and the latter cooperated with the English in the campaign of 893 (or 894). That Alfred sent alms to Irish as well as to European monasteries may be taken on Asser's authority. The visit of the three pilgrim "Scots" (i.e. Irish) to Alfred in 891 is undoubtedly authentic. The story that he himself in his childhood was sent to Ireland to be healed by Saint Modwenna, though mythical, may show Alfred's interest in that island.

Religion and culture

Very little is known of the church under Alfred. The Danish attacks had been particularly damaging to the monasteries, and though Alfred founded two or three new monasteries and enticed foreign monks to England, monasticism did not revive significantly during his reign. The Danish raids had also an impact on learning, leading to the practical extinction of Latin even among the clergy: the preface to Alfred's translation of Pope Gregory I's Pastoral Care into Old English bearing eloquent, if not impartial witness, to this.

Alfred established a court school, following the example of Charlemagne.[9] To this end, he imported scholars like Grimbald and John the Saxon from Europe, and Asser from South Wales. Not only did the King see to his own education, he also made the series of translations for the instruction of his clergy and people, most of which survive. These belong to the later part of his reign, probably the last four years, of which the chronicles are almost silent.

Apart from the lost Handboc or Encheiridion, which seems to have been merely a commonplace book kept by the king, the earliest work to be translated was the Dialogues of Gregory, a book greatly popular in the Middle Ages. In this case the translation was made by Alfred's great friend Werferth, Bishop of Worcester, the king merely furnishing a foreword. The next work to be undertaken was Gregory's Pastoral Care, especially for the good of the parish clergy. In this, Alfred keeps very close to his original; but the introduction which he prefixed to it is one of the most interesting documents of the reign, or indeed of English history. The next two works taken in hand were historical, the Universal History of Orosius and Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. The priority should likely be given to the Orosius, but the point has been much debated. In the Orosius, by omissions and additions, Alfred so remodels his original as to produce an almost new work; in the Bede the author's text is closely stuck to, no additions being made, though most of the documents and some other less interesting matters are omitted. Of late years doubts have been raised as to Alfred's authorship of the Bede translation. But the skeptics cannot be regarded as having proved their point.

Alfred's translation of The Consolation of Philosophy of Boethius was the most popular philosophical handbook of the Middle Ages. Here again Alfred deals very freely with his original and though the late Dr. G. Schepss showed that many of the additions to the text are to be traced not to Alfred himself, but to the glosses and commentaries which he used, still there is much in the work which is solely Alfred's and highly characteristic of his genius. It is in the Boethius that the oft-quoted sentence occurs: "My will was to live worthily as long as I lived, and after my life to leave to them that should come after, my memory in good works." The book has come down to us in two manuscripts only. In one of these[10] the writing is prose, in the other[11] a combination of prose and alliterating verse. The latter manuscript was severely damaged in the 18th and 19th centuries,[12] and the authorship of the verse has been much disputed; but likely it also is by Alfred. In fact, he writes in the prelude that he first created a prose work and then used it as the basis for his poem, the Lays of Boethius, his crowning literary achievement. He spent a great deal of time working on these books, which he tells us he gradually wrote through the many stressful times of his reign to refresh his mind. Of the authenticity of the work as a whole there has never been any doubt.

The last of Alfred's works is one to which he gave the name Blostman, i.e., "Blooms" or Anthology. The first half is based mainly on the Soliloquies of St Augustine of Hippo, the remainder is drawn from various sources, and contains much that is Alfred's own and highly characteristic of him. The last words of it may be quoted; they form a fitting epitaph for the noblest of English kings. "Therefore he seems to me a very foolish man, and truly wretched, who will not increase his understanding while he is in the world, and ever wish and long to reach that endless life where all shall be made clear."

Beside these works of Alfred's, the Saxon Chronicle almost certainly, and a Saxon Martyrology, of which fragments only exist, probably owe their inspiration to him. A prose version of the first fifty Psalms has been attributed to him; and the attribution, though not proved, is perfectly possible. Additionally, Alfred appears as a character in The Owl and the Nightingale, where his wisdom and skill with proverbs is attested. Additionally, The Proverbs of Alfred, which exists for us in a thirteenth century manuscript contains sayings that very likely have their origins partly with the king.

The Alfred jewel, discovered in Somerset in 1693, has long been associated with King Alfred because of its Old English inscription "AELFRED MEC HEHT GEWYRCAN" (Alfred Ordered Me To Be Made). This relic, of unknown use, certainly dates from Alfred's reign but it is possibly just one of several that once existed. The inscription does little to clarify the identity of the central figure which has long been believed to depict God or Christ.

Veneration

Alfred is venerated as a Saint by the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church and is regarded as a hero of the Christian Church in the Anglican Communion, with a feast day of 26 October,[13] and may often be found depicted in stained glass in Church of England parish churches. Also, Alfred University was named after him; a large statue of his likeness is in the center of campus.

Family

In 868, Alfred married Ealhswith, daughter of Ealdorman of the Gaini (who is also known as Aethelred Mucill), who was from the Gainsborough region of Lincolnshire. She appears to have been the maternal granddaughter of a King of Mercia. They had five or six children together, including Edward the Elder, who succeeded his father as king, Ethelfleda, who would become Queen of Mercia in her own right, and Ælfthryth who married Baldwin II the Count of Flanders. His mother was Osburga daughter of Oslac of the Isle of Wight, Chief Butler of England. Asser, in his Vita Alfredi asserts that this shows his lineage from the Jutes of the Isle of Wight. This is unlikely as Bede tells us that they were all slaughtered by the Saxon under Caedwalla. However, ironically Alfred could trace his line via the House of Wessex itself, from King Wihtred of Kent, whose mother was the sister of the last Island King, Arwald.

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Æthelflæd | 918 | Married 889, Ealdorman Ethelred of Mercia d 910; had issue. | |

| Edward | 870 | 17 July 924 | Married (1) Ecgwynn, (2) Ælfflæd, (3) 919 Edgiva |

| Æthelgiva | Abbess of Shaftesbury | ||

| Ælfthryth | 929 | Married Baldwin, Count of Flanders; had issue | |

| Æthelwærd | 16 October 922 | Married and had issue |

Ancestry

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16. Eafa | |||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

8. Ealhmund of Kent |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

4. Egbert of Wessex |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

2. Æthelwulf of Wessex |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

5. Redburga |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

1. Alfred the Great |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. Oslac |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

3. Osburga |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Death, burial and legacy

Alfred died on 26 October. The actual year is not certain, but it was not necessarily 901 as stated in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. How he died is unknown, although he suffered throughout his life with a painful and unpleasant illness- probably Crohn's Disease, which seems to have been inherited by his grandson king Edred. He was originally buried temporarily in the Old Minster in Winchester, then moved to the New Minster (perhaps built especially to receive his body). When the New Minster moved to Hyde, a little north of the city, in 1110, the monks transferred to Hyde Abbey along with Alfred's body. During the reign of Henry VIII his crypt was looted by the new, Anglican owners of the old church in which he had been laid to rest. His coffin was melted down for its lead and his bones were unceremoniously reburied in the churchyard. This grave was apparently excavated during the building of a new prison in 1788 and the bones scattered. However, bones found on a similar site in the 1860s were also declared to be Alfred's and later buried in Hyde churchyard. Extensive excavations in 1999 revealed what is believed to be his grave-cut, that of his wife Eahlswith, and that of their son Edward the Elder but barely any human remains.[14]

A number of educational establishments are named in Alfred's honour. These are:

- The University of Winchester was named 'King Alfred's College, Winchester' between 1840 and 2004, whereupon it was re-named "University College Winchester".

- Alfred University, as well as Alfred State College located in Alfred, NY, are both named after the king.

- In honour of Alfred, the University of Liverpool created a King Alfred Chair of English Literature.

- University College, Oxford is erroneously said to have been founded by King Alfred.

- King Alfred's College, a secondary school in Wantage, Oxfordshire. The Birthplace of Alfred.

- King's Lodge School, in Chippenham, Wiltshire is so named because King Alfred's hunting lodge is reputed to have stood on or near the site of the school.

- The King Alfred School & Specialist Sports Academy, Burnham Road, Highbridge is so named due to its rough proximity to Brent Knoll (a Beacon Site) and Athelny.

- The King Alfred School in Barnet, North London, UK.

Wantage Statue

The statue of Alfred the Great, situated in the Wantage market place, was sculpted by Count Gleichen, a relative of Queen Victoria, and unveiled on 14 July 1877 by the Prince and Princess of Wales, the future Edward VII and his wife.[15]

The statue was vandalised on New Year's Eve 2007, losing part of its right arm.[15]

See also

- British military history

- Kingdom of England

- Lays of Boethius

- Alfred Jewel

References

- ↑ Canute the Great, who ruled England from 1016 to 1035, was Danish.

- ↑ Alfred was the youngest of either four (Weir, Alison, Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy (1989), p. 5.) or five brothers,[1] the primary record conflicting regarding whether Æthelstan of Wessex was a brother or uncle.

- ↑ The Life of King Alfred

- ↑ Wormald, Patrick, 'Alfred (848/9-899)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004).

- ↑ History of the Monarchy - The Anglo-Saxon Kings - Alfred 'The Great'

- ↑ Churchill, Sir Winston: The Island Race, Corgi, London, 1964, II, p. 219.

- ↑ Lee, F. N., King Alfred the Great and our Common Law Department of Church History, Queensland Presbyterian Theological Seminary, Brisbane, Australia, August 2000

- ↑ Reports of Cases Determined in the General Court, appendix. Thomas Jefferson.

- ↑ Codicology of the court school of Charlemagne: Gospel book production, illumination, and emphasised script (European university studies. Series 28, History of art) ISBN 3820472835

- ↑ Oxford Bodleian Library MS Bodley 180

- ↑ British Library Cotton MS Otho A. vi

- ↑ Kiernan, Kevin S., "Alfred the Great's Burnt Boethius". In Bornstein, George and Theresa Tinkle, eds., The Iconic Page in Manuscript, Print, and Digital Culture (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998).

- ↑ Gross, Ernie (1990). This Day In Religion. New York: Neal-Schuman Publishers, Inc..

- ↑ Dodson, Aidan (2004). The Royal Tombs of Great Britain. London: Duckworth.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 ""Wantage Herald Article"".

Further reading

- Pratt, David: The political thought of King Alfred the Great (Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought: Fourth Series, 2007) ISBN

9780521803502

- Parker, Joanne: England's Darling The Victorian Cult of Alfred the Great, 2007, ISBN 9780719073564

- Pollard, Justin: Alfred the Great : the man who made England, 2006, ISBN 0719566665

- Fry, Fred: Patterns of Power: The Military Campaigns of Alfred the Great, 2006, ISBN 9781905226931

- Giles, J. A. (ed.): The Whole Works of King Alfred the Great (Jubilee Edition, 3 vols, Oxford and Cambridge, 1858)

- The whole works of King Alfred the Great, with preliminary essays, illustrative of the history, arts, and manners, of the ninth century, 1969, OCLC 28387

- For a novelization of King Alfred's exploits, there is Bernard Cornwell's series, beginning with The Last Kingdom.

External links

- The Life of King Alfred translated by Dr. J.A. Giles (London, 1847).

- Britannia History Bishop Asser's Life of King Alfred

- Documentary - The Making of England: King Alfred

- An Illustrated Biography of Alfred the Great

- Alfred the Great

- official website of the British Monarchy

- King Alfred the Great

- Alfred Jewel

- Lays of Boethius

- Royal Berkshire History: King Alfred the Great

- Alfred's Palace

- Orosius (c. 417), Alfred the Great; Barrington, Daines, eds., The Anglo-Saxon Version, from the Historian Orosius, London, 1773, http://books.google.com/books?id=aT0JAAAAQAAJ, retrieved on 2008-08-17

|

Alfred the Great

House of Wessex

Born: 849 Died: 26 October 899 |

||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ethelred |

King of Wessex 871 – 899 |

Succeeded by Edward the Elder |

| Preceded by New title |

King of England 878 – 899 |

Succeeded by Edward the Elder |

| Preceded by Ethelred |

Bretwalda 871 – 899 |

Last holder |

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Alfred the Great |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Ælfred |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | King of Wessex |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 849 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Wantage, England |

| DATE OF DEATH | 26 October 899 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | ? |