Alfred Wegener

| Alfred Wegener | |

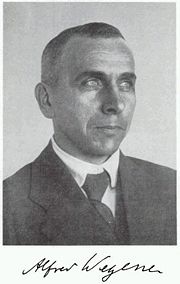

Alfred Wegener, around 1925

|

|

| Born | November 1, 1880 Berlin |

|---|---|

| Died | November 2, 1930 (aged 50) Greenland |

| Nationality | German |

| Fields | meteorology geology |

| Alma mater | University of Berlin |

Alfred Lothar Wegener (1 November 1880 – 2 November 1930) was a German scientist, geologist and meteorologist. He was born in Berlin. He is most notable for his theory of continental drift (Kontinentalverschiebung), proposed in 1915, which hypothesized that the continents were slowly drifting around the Earth. However, at the time he was unable to demonstrate a mechanism for this movement; this combined with a lack of solid evidence meant that his hypothesis was not accepted until the 1950s, when numerous discoveries provided evidence of continental drift.[1]

Contents |

Career

Alfred Wegener had early training in astronomy (Ph.D., University of Berlin, 1904). He became very interested in the new discipline of meteorology (he married the daughter of famous meteorologist and climatologist Wladimir Köppen) and as a record-holding balloonist himself, pioneered the use of weather balloons to track air masses. His lectures became a standard textbook in meteorology, The Thermodynamics of the Atmosphere. Wegener was part of several expeditions to Greenland to study polar air circulation, when the existence of a jet stream itself was highly controversial.

On his last expedition, in Greenland, Alfred Wegener and his companion Rasmus Villumsen became lost in a blizzard and went missing in November 1930. Wegener's body was found on 12 May 1931. His suspected cause of death was heart failure through overexertion.

Continental drift

Browsing the library at the University of Marburg, where he was teaching in 1911, Wegener was struck by the occurrence of identical fossils in geological strata that are now separated by oceans. The accepted explanations or theories at the time posited land bridges to explain the fossil anomalies; animals and plants could have migrated between fixed separate continents by crossing the land bridges. But Wegener was increasingly convinced that the continents themselves had shifted away from a primal single massive supercontinent, which drifted apart about 180 million years ago, to judge from the fossil evidence.[2] Wegener used land features, fossils, and climate as evidence to support his hypothesis of continental drift. Examples of land features such as mountain ranges in Africa and South America lined up; also coal fields on Europe matched up with coal fields in North America. Wegener noticed that fossils from reptiles such as Mesosaurus and Lystrosaurus were found in places that are now separated by oceans. Since neither reptile could have swum great distances, Wegener inferred that these reptiles had once lived on a single landmass that split apart.

From 1912 he publicly advocated the theory of "continental drift", arguing that all the continents were once joined together in a single landmass and have drifted apart.

In 1915, in The Origin of Continents and Oceans (Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane), Wegener published the theory that there had once been a giant supercontinent, which, in later editions, he named "Pangaea" (meaning "All-Lands" or "All-Earth") and drew together evidence from various fields. Expanded editions during the 1920s presented the accumulating evidence. The last edition, just before his untimely death, revealed the significant observation that shallower oceans were geologically younger.

Theory of centrifugal force

Alfred Wegener also came up with a theory to explain continental drift, although it was in error. His theory of continental drift proposed that centrifugal force moved the heavy continents toward the equator as the Earth spun. He thought that inertia, from centrifugal movement combined with tidal drag on the continents (caused by the gravitational pull of the sun and moon) would account for continental drift.

Reaction

In his work, Wegener presented a large amount of circumstantial evidence in support of continental drift, but he was unable to come up with a convincing mechanism. Thus, while his ideas attracted a few early supporters such as Alexander Du Toit from South Africa and Arthur Holmes in England, the hypothesis was generally met with skepticism. The one American edition of Wegener's work, published in 1924, was received so poorly that the American Association of Petroleum Geologists organized a symposium specifically in opposition to the continental drift hypothesis. Also its opponents could, as did the Leipziger geologist Franz Kossmat, argue that the oceanic crust was too firm for the continents to "simply plow through". In 1943 George Gaylord Simpson wrote a vehement attack on the theory (as well as the rival theory of sunken land bridges) and put forward his own permanantist views [3]. Alexander du Toit wrote a rejoinder in the following year[4], but such was G.G.Simpson's influence that even in countries previously sympathetic towards continental drift, like Australia, Wegener's hypotheis fell out of favour.

In the early 1950s, the new science of paleomagnetism pioneered at Cambridge University by S. K. Runcorn and at Imperial College by P.M.S. Blackett was soon throwing up data in favour of Wegener's theory. By early 1953 samples taken from India showed that the country had previously been in the Southern hemisphere as predicted by Wegener. By 1959, the theory had enough supporting data that minds were starting to change, particularly in the United Kingdom where, in 1964, the Royal Society held a symposium on the subject.[5]

Additionally, the 1960s saw several developments in geology, notably the discoveries of seafloor spreading and Wadati-Benioff zones, led to the rapid resurrection of the continental drift hypothesis and its direct descendant, the theory of plate tectonics. Alfred Wegener was quickly recognized as a founding father of one of the major scientific revolutions of the 20th century.

Awards and honors

The Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven, Germany, was established in 1980 on his centenary. It awards the Wegener Medal in his name.[6] The Wegener impact craters on both Mars and the Moon, as well as the asteroid 29227 Wegener and the peninsula where he died in Greenland (Wegener Peninsula near Ummannaq, ), are named after him.[7]

The European Geosciences Union sponsors an Alfred Wegener Medal & Honorary Membership "for scientists who have achieved exceptional international standing in atmospheric, hydrological or ocean sciences, defined in their widest senses, for their merit and their scientific achievements."[8]

See also

References

- ↑ Spaulding, Nancy E., and Samuel N. Namowitz. Earth Science. Boston: McDougal Littell, 2005.

- ↑ http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/wegener.html Alfred Wegener (1880-1930)

- ↑ G.G. Simpson, "Mammals and the Nature of Continents", American Journal of Science 241 (1943):1-31

- ↑ A. du Toit, "Tertiary Mammals and Continental Drift", American Journal of Science 242 (1944): 145-63

- ↑ H. Frankel, "The Continental Drift", in "Scientific Controversies: Case Solutions in the resolution and closure of disputes in science and technology", ed. H.T. Engelhardt Jr and A.L. Caplan, Cambridge Univeristy Press (1987)

- ↑ http://www.awi.de/fileadmin/user_upload/News/Print_Products/PDF/252-265_Kap12.pdf Alfred Wegener Institute, 2005 Annual report, page 259

- ↑ JPL Small-Body Database Browser

- ↑ "EGU: Awards & Medals". Retrieved on 2009-09-16.

Further reading

- Wegener, Alfred (1966). The Origin of Continents and Oceans. New York: Dover.- (Translated from the fourth revised German edition by John Biram)

- Wegener, Alfred (1968). The Origin of Continents and Oceans. London: Methuen.- (Translated from the fourth German edition by John Biram with an introduction by B.C. King)

- Wegener, Elsie (Editor, with the assistance of Dr. Fritz Loewe) (1939). Greenland Journey, The Story of Wegener’s German Expedition to Greenland in 1930-31 as told by Members of the Expedition and the Leader’s Diary. London: Blackie & Son Ltd..- (Translated from the seventh German edition by Winifred M. Deans)

- Wegener, Alfred (1911). Thermodynamik der Atmosphäre. Leipzig: Verlag Von Johann Ambrosius Barth. http://books.google.com/books?id=slxDAAAAIAAJ&pg=PR1&dq=alfred+wegener&lr=&as_brr=1#PPR1,M2.- (Wegener's Thermodynamics of the Atmosphere)