Albanian language

| Albanian Shqip |

||

|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation: | [ʃcip] | |

| Spoken in: | Albania (official), Kosovo (official), Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Greece, U.S.A., Italy, Germany, United Kingdom, Turkey, Switzerland, Canada, Australia & other countries. | |

| Region: | Southeastern Europe | |

| Total speakers: | 6,000,000[1] | |

| Language family: | Indo-European Albanian |

|

| Writing system: | Latin alphabet (Albanian variant) | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language in: | and recognised as a minority language in: |

|

| Regulated by: | No official regulation | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1: | sq | |

| ISO 639-2: | alb (B) | sqi (T) |

| ISO 639-3: | variously: sqi – Albanian (generic) aln – Gheg aae – Arbëreshë aat – Arvanitika als – Tosk |

|

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Albanian (Gjuha shqipe pronounced [ˈɟuha ˈʃcipɛ]) is an Indo-European language spoken by nearly 6 million people,[1] primarily in Albania and Kosovo but also in other areas of the Balkans in which there is an Albanian population, including the west of Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro, and southern Serbia. Albanian is also spoken by communities in Greece, along the eastern coast of southern Italy, and on the island of Sicily. Additionally, speakers of Albanian can be found elsewhere throughout the latter two countries resulting from a modern diaspora, originating from the Balkans, that also includes Scandinavia, Switzerland, Germany, United Kingdom, Turkey, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States. An estimated 3 million Albanians are believed to be the total of the diaspora concentrated mostly in Western Europe and North America.

Contents |

History

First documents found

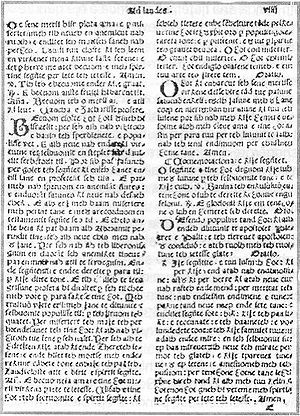

The fisrt document found in albanian are "Formula e pagëzimit"(1462) (Baptesimal formula),issued by Pal Engjëlli archbishop of Durrës;the second is "Fjalori i Arnold von Harf"it (Arnold von Harf vocabulary) in 1469;the third document "Ungjilli i Pashkëve" or Ungjilli i Shën Mateut date in XV century. The first book in albanian was written by Gjon Buzuku of 20 March 1554 to 5 January 1555. The book was written in Gheg dialect in latin alphabet with some slavic letters adapted for albanian vowels.

After Ottoman conquest

In 1635 Frang Bardhi published in Rome his Dictionarum latinum-epiroticum, the fisrt known Latin-Albanian dictionary. the evidence shows,moreover, that "the study of albanian has a tradition of 350 years" and inculdes works of Frang Bardhi (1606-1643), Andre Bogdani(1600-1685),Nilo Katalanos(1637-1694) and others.

The alphabet used by romanthics

History of alphabet

From November 14 to November 22, 1908, albanian intellectuals meet in Manastir (Bitolja, Macedonia), at the Congress of Manastir to standardize the Albanian alphabet using the Latin script. Up to now, Latin, Cyrillic and Arabic script had been used.

Standard alanian

In 1970's the publications in Tirana, followed by repubication in Prishtina of a book of orthographical rules, Drejtëshkrimi i gjuhës shqipe followed by a widely distributed authoritative dictionary in 1976 "Fjalori drejtshkrimor i gjuhës shqipe", created a considerable degreeof phonological normalization as well as spelling reform.

Classification

Albanian was proven to be an Indo-European language in 1854 by the philologist Franz Bopp. The Albanian language constitutes its own branch of the Indo-European language family.

Some scholars believe that Albanian derives from Illyrian[2][3] while others,[4] claim that it derives from Daco-Thracian. (Illyrian and Daco-Thracian, however, may have formed a sprachbund; see Thraco-Illyrian.)

Establishing longer relations, Albanian is often compared to Balto-Slavic on the one hand and Germanic on the other, both of which share a number of isoglosses with Albanian. Moreover, Albanian has undergone a vowel shift in which stressed, long o has fallen to a, much like in the former and opposite the latter. Likewise, Albanian has taken the old relative jos and innovatively used it exclusively to qualify adjectives, much in the way Balto-Slavic has used this word to provide the definite ending of adjectives.

Other linguists link Albanian with Greek and Armenian, while placing Germanic and Balto-Slavic in another branch of Indo-European.[5][6][7]

Comparison with other Indo-European languages

| Albanian | muaj | i ri / e re | nënë/mëmë | motër | natë | hundë | tre | i zi /e zezë | i kuq / e kuqe | i/ e gjelbër/blertë | i/e verdhë | ujk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other Indo-European languages | ||||||||||||

| Sanskrit | māsa | nava | mātṛ | svasṛ | nakti | nasa | tri | kāla | rudhira | hari | pīta | vṛka |

| Persian | māh | nou | mādar | xāhar | shab | biní | se | siāh | sorkh | sabz | zard | gorg |

| Ancient Greek | μήν mēn |

νέος néos |

μήτηρ mētēr |

αδελφή adelphē |

νύξ nýx |

ῥίς rhís |

τρεῖς treïs |

μέλας mélas |

ἐρυθρός erythrós |

χλωρός khlōrós |

ξανθός xanthós |

λύκος lýkos |

| Latin | mēnsis | novus | māter | soror | nox | nasus | trēs | āter, niger | ruber | viridis | flāvus, gilvus | lupus |

| Romanian | lună | nou | mamă | soră | noapte | nas | trei | negru | roşu | verde | galben | lup |

| Serbian | месец mesec |

нов nov |

мајка majka |

сестра sestra |

ноћ noć |

нос nos |

три tri |

црн crn |

црвен crven |

зелен zelen |

жут žut |

вук vuk |

| Latvian | mēnesis | jauns | māte | māsa | nakts | deguns | trīs | melns | sarkans | zaļš | dzeltens | vilks |

| English | month | new | mother | sister | night | nose | three | black | red | green | yellow | wolf |

| Irish | mí | nua | máthair | deirfiúr | oiche | srón | trí | dubh | dearg, rua | glas, uaine | buí | mac tíre, faolchú |

| Armenian | ամիս amis |

նոր nor |

մայր mayr |

քույր k'owyr |

գիշեր gišer |

քիթ k'it |

երեք erek' |

սեւ sev |

կարմիր karmir |

կանաչ kanač |

դեղին deġin |

գայլ gayl |

Geographic distribution

|

Indo-European topics |

|---|

| Indo-European languages |

| Albanian · Armenian · Baltic Celtic · Germanic · Greek Indo-Iranian (Indo-Aryan, Iranian) Italic · Slavic extinct: Anatolian · Paleo-Balkans (Dacian, |

| Indo-European peoples |

| Albanians · Armenians Balts · Celts · Germanic peoples Greeks · Indo-Aryans Iranians · Latins · Slavs historical: Anatolians (Hittites, Luwians) |

| Proto-Indo-Europeans |

| Language · Society · Religion |

| Urheimat hypotheses |

| Kurgan hypothesis Anatolia · Armenia · India · PCT |

| Indo-European studies |

Albanian is spoken by nearly 6 million people[1] mainly in Albania, Kosovo, Italy (Arbereshe), Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro, Greece (Arvanites or Arvanitians), Turkey, Bulgaria and Romania; and by immigrant communities in many countries such as Belgium, Egypt, Germany, Greece, Italy, Sweden, Turkey (Europe), Russia, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, Canada, the United States, and Australia.

Official status

Albanian in a revised form of the Tosk dialect is the official language of Albania and Kosovo; and is official in the municipalities where there are more than 22% ethnic Albanian inhabitants in the Republic of Macedonia. It is also an official language of Montenegro where it is spoken in the municipalities with ethnic Albanian populations.

Dialects

Albanian can be divided into three dialects: Gheg and Tosk with a transitional dialect zone between them.[8]

The Shkumbin river is roughly the dividing line, with Gheg spoken north of the Shkumbin and Tosk south of it. The Gheg literary language has been documented since 1462. Until the Communists took power in Albania, the standard was based on Gheg. Although the literary versions of Tosk and Gheg are mutually intelligible, many of the regional dialects are not.

Gheg is divided into four sub-dialects: Northwest Gheg, Northeast Gheg, Central Gheg, and Southern Gheg. Northwest Gheg is spoken in all of Montenegro, Lezhë, Mirditë, Pukë and Shkodër. Northeast Gheg is spoken in all of Kosovo, Has, Kukës and Tropojë. Central Gheg is spoken in Debar, Gostivar, Krujë, Peshkopi, Mat, Struga and Tetovo. Southern Gheg is spoken in Durrës, Elbasan, Kavajë and Tirana.

The transitional dialects are spoken in Cërrik, Dumresë, Polisit, Lushnjë, Rajcë, Shpatit, Sulovë and Vërçës. They have features of both Tosk and Gheg, including the rhotacism of Tosk and the nasal vowels of Gheg.

Tosk is divided into five sub-dialects: Northern Tosk, Labërisht, Çam, Arvanitika and Arbërisht. Northern Tosk is spoken in Berat, Fier, Gramsh, Kolonjë, Korçë, Ohrid, Pogradec, Prespa and northern Vlorë. Labërisht is spoken in southern Vlorë, Dukat, Tepelenë, Himarë, Mallakastër, Përmet, Delvinë, Gjirokastër and Sarandë. Çam is spoken in extreme southern Albania such as Xarrë and northern Greece. Arvanitika is spoken in southern Greece by the Arvanites in Joanina, Paramithia, Filat, Margarit, Arta, Preveza, Kastoria, Florina, Parga. Arbërisht is spoken by the Arbëreshë, descendants of 15th and 16th century immigrants in southeastern Italy, in small communities in the regions of Sicily, Calabria, Basilicata, Campania, Molise, Abruzzi, and Puglia. Tosk sub-dialects are spoken by most members of the large Albanian immigrant communities of Egypt, Turkey, Ukraine, and all of Europe.

Gheg and Tosk differ mainly by:

- rhotacism - Gheg has n where Tosk has r

- late Proto-Albanian ā + tautosyllabic nasal > Gheg low-central or low-back vowel; > Tosk mid-central, or low-front-to-central vowel

- Proto-Albanian ō > uo > Gheg vo, Tosk va

- infinitival use of verbal adjective preceded in Gheg by me and in Tosk by për të

- difference in lexemes, noun plurals, suppletion of the aorist system of the verb

Subdialects may vary based on:

- retention or loss of final schwa (-ë)

- devoicing of final voiced segments

- treatment of intervocalic and final nj

- treatment of clusters of nasal + voiced stop

- development of anaptyctic homorganic stops after nasals that follow a stressed vowel and precede unstressed -ël or -ër

- treatment of vowel clusters ie, ye, and ua

- treatment of stressed /e/ before a nasal

Notable phonological and lexicological differences between Tosk and Gheg

| Standard form | Tosk form | Gheg form | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shqipëri | Shqipëri | Shqypni/ Shipni/ Shqipni | Albania |

| një | një | nji/njâ/njo | a/one |

| nëntë | nëntë/nëndë | nândë/nant/non | nine |

| është | është | âsht/osht/â | is |

| bëj | bëj | bâj/boj | do |

| emër | emër | êmën | name |

| pjekuri | pjekuri | pjekuni | maturity |

| gjendje | gjëndje | gjêndje | situation |

| zog | zok | zog | bird |

| mbret | mbret | mret | king |

| për të punuar | për të punuar | me punue/me punau | to work |

| rërë | rërë | rânë/zall | sand |

| qenë | qënë | kênë / kânë | been (part.) |

| dëllinjë | enjë | bërshê | juniper |

| baltë | baltë | bâltë / lloç | mud |

| cimbidh | mashë | danë | tongs |

| sy | sy/si | sy/sö | eye |

( ˆ ) denotes nasal vowels, which are a common feature of Gheg.

Sounds

Standard Albanian has 7 vowels and 29 consonants. Gheg uses long and nasal vowels which are absent in Tosk. Another peculiarity is the mid-central vowel "ë" reduced at the end of the word. The stress is fixed mainly on the penultimate syllable.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||||

| Plosive | p b | t d | c ɟ | k ɡ | ||||

| Affricate | ts dz | tʃ dʒ | ||||||

| Fricative | f v | θ ð | s z | ʃ ʒ | h | |||

| Trill | r | |||||||

| Flap | ɾ | |||||||

| Approximant | l ɫ | j |

| IPA | Description | Written as | Pronounced as in |

|---|---|---|---|

| p | Voiceless bilabial plosive | p | pen |

| b | Voiced bilabial plosive | b | bat |

| t | Voiceless alveolar plosive | t | tan |

| d | Voiced alveolar plosive | d | debt |

| c | Voiceless palatal plosive | q | similar to get you |

| ɟ | Voiced palatal plosive | gj | similar to told you |

| k | Voiceless velar plosive | k | car |

| g | Voiced velar plosive | g | go |

| ts | Voiceless alveolar affricate | c | hats |

| dz | Voiced alveolar affricate | x | goods |

| tʃ | Voiceless postalveolar affricate | ç | chin |

| dʒ | Voiced postalveolar affricate | xh | jet |

| θ | Voiceless dental fricative | th | thin |

| ð | Voiced dental fricative | dh | then |

| f | Voiceless labiodental fricative | f | far |

| v | Voiced labiodental fricative | v | van |

| s | Voiceless alveolar fricative | s | son |

| z | Voiced alveolar fricative | z | zip |

| ʃ | Voiceless postalveolar fricative | sh | show |

| ʒ | Voiced postalveolar fricative | zh | vision |

| h | Voiceless glottal fricative | h | hat |

| m | Bilabial nasal | m | man |

| n | Alveolar nasal | n | not |

| ɲ | Palatal nasal | nj | Spanish señor |

| j | Palatal approximant | j | yes |

| l | Alveolar lateral approximant | l | lean |

| ɫ | Velarized alveolar lateral approximant | ll | ball |

| r | Alveolar trill | rr | Spanish hierro |

| ɾ | Alveolar tap | r | Spanish aro |

Notes:

- The palatal stops /c/ and /ɟ/ have no English equivalent, so the pronunciation guide is approximate. Palatal stops can be found in other languages, for example, in Hungarian (where these sounds are spelled ty and gy respectively).

- The palatal nasal /ɲ/ corresponds to the sound of the Spanish ñ or the French or Italian digraph gn (as in gnocchi). It is pronounced as one sound, not a nasal plus a glide.

- The ll sound is a velarised lateral, close to English dark L.

- The contrast between flapped r and trilled rr is the same as in Spanish. English does not have either of the two sounds phonemically (but tt in butter is pronounced as a flap r in most American dialects).

- The letter ç can be spelt ch on American English keyboards, both due to its English sound. (Usually, however, it's spelled simply c or more rarely q, which may cause confusion ; however, meanings are usually understood).

Vowels

| IPA | Description | Written as | Pronounced as in |

|---|---|---|---|

| i | Close front unrounded vowel | i | bead |

| ɛ | Open-mid front unrounded vowel | e | bed |

| a | Open front unrounded vowel | a | Spanish casa |

| ə | Schwa | ë | about |

| ɔ | Open-mid back rounded vowel | o | four |

| y | Close front rounded vowel | y | French tu, German über |

| u | Close back rounded vowel | u | boot |

Grammar

Albanian nouns are inflected by gender (masculine, feminine and neuter) and number (singular and plural). There are 5 declensions with 6 cases (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, ablative and vocative), although the vocative only occurs with a limited number of words. The cases apply to both definite and indefinite nouns and there are numerous cases of syncretism. The equivalent of a genitive is formed by using the prepositions i/e/të/së with the dative.

The following shows the declension of the masculine noun mal (mountain):

| Indefinite Singular | Indefinite Plural | Definite Singular | Definite Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | mal (mountain) | male (mountains) | mali (the mountain) | malet (the mountains) |

| Accusative | mal | male | malin | malet |

| Genitive | i/e/të/së mali | i/e/të/së maleve | i/e/të/së malit | i/e/të/së maleve |

| Dative | mali | maleve | malit | maleve |

| Ablative | mali | maleve/malesh | malit | maleve |

The following table shows the declension of the feminine noun vajzë (girl)

| Indefinite Singular | Indefinite Plural | Definite Singular | Definite Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | vajzë (girl) | vajza (girls) | vajza (the girl) | vajzat (the girls) |

| Accusative | vajzë | vajza | vajzën | vajzat |

| Genitive | i/e/të/së vajze | i/e/të/së vajzave | i/e/të/së vajzës | i/e/të/së vajzave |

| Dative | vajze | vajzave | vajzës | vajzave |

| Ablative | vajze | vajzave/vajzash | vajzës | vajzave |

The definite article is placed after the noun as in many other Balkan languages, for example Romanian and Bulgarian.

- The definite article can be in the form of noun suffixes, which vary with gender and case.

- For example in singular nominative, masculine nouns add -i, or those ending in -g/-k, take -u (to avoid palatalization):

- mal (mountain) / mali (the mountain);

- libër (book) / libri (the book);

- zog (bird) / zogu (the bird).

- Feminine nouns take the suffix -(j)a:

- veturë (car) / vetura (the car);

- shtëpi (house) / shtëpia (the house);

- lule (flower) / lulja (the flower).

- For example in singular nominative, masculine nouns add -i, or those ending in -g/-k, take -u (to avoid palatalization):

- Neuter nouns take -t.

Albanian has developed an analytical verbal structure in place of the earlier synthetic system, inherited from Proto-Indo-European. Its complex system of moods (6 types) and tenses (3 simple and 5 complex constructions) is distinctive among Balkan languages. There are two general types of conjugation. In Albanian the constituent order is subject verb object and negation is expressed by the particles nuk or s' in front of the verb, for example:

- Toni nuk flet anglisht "Tony does not speak English" ;

- Toni s'flet anglisht "Tony doesn't speak English" ;

- Nuk e di "I do not know" ;

- S'e di "I don't know".

In imperative sentences, the particle mos is used :

- Mos harro "do not forget!".

However, with verbs in the non-active form (forma joveprore), the verb is often in sentence-initial position :

- Parashikohet një ndërprerje "An interruption is anticipated".

Vocabulary

Cognates with Illyrian

See Illyrian languages

- brisa, "husk of grapes"; cf. Alb bërsí "lees, dregs; mash" (< PA *brutiā)

- loúgeon, "pool"; cf. Alb lag "to wet, soak, bathe, wash" (< PA *lauga), lëgatë "pool" (< PA *leugatâ), lakshte "dew" (< PA *laugista)

- mandos, "small horse"; cf. Alb mëz, mâz "poney", Mess Iuppiter Menzana "supreme deity", Manduria "town in Apulia", Skt mandura "stable for horses", Thrac Mezenai "divine horseman".

- rhinos, "fog, mist"; cf. OAlb ren, mod. Alb re, rê "cloud" (< PA *rina)

Early Greek loans

Early Greek loandwords borrowed into Albanian were mainly commodity items and trade goods.

- bagëm "oil for anointment" < Gk báptisma "anointment"

- bletë "hive; bee" < Greco-Latin < Gk (Attic) mélitta "honey-bee" (vs. Gk (Ionic) mélissa)[9].

- brukë "tamarisk" < Gk mourikē

- drapër "sickle" < Gk (NW) drápanon

- keq "bad, evil < Gk kakos

- kopsht "garden" < Gk (NW) kāpos

- kumbull "plum" < Gk kokkumēlon

- lakër "cabbage, green vegetables" < Gk lákhanon "green; vegetable"

- lëpjetë "orach, dock" < Gk lápathon

- lyej "to smear, oil" < *elaiwā < Gk elai(w)on "oil"

- mokër "millstone" < Gk (NW) mākhaná "device, instrument"

- ngjalë "eel" < Gk enchelys

- pjepër "melon" < Gk pépon "melon"

- presh "leek" < Gk práson

- shpellë "cave" < Gk spēlaion "cave"

- trumzë "thyme" < Gk thýmbra, thrýmbē

- udhë "road, way" < Gk odos

Gothic loans

Some were borrowed through Late Latin, while others came from the Ostrogothic expansion into parts of Praevalitana around Nakšić and the Gulf of Kotor in Montenegro.

- fat "groom, husband" < Goth brūþfaþs "bridegroom"[10]

- gomar "donkey, ass" < *margë < Goth *marh "horse"

- petk "herder's coat; clothing" < Goth paida; cf. OHG pfeit, OE pād

- shkulkë "branch indicating a pasture is off limits" < Goth skulka "guardian"

- shkumë "foam" < Goth scūma

- tirq "trousers" < Late Latin tubrucus < Goth *þiobroc "knee-britches"; cf. OHG dioh-bruoh

The earliest accepted document in the Albanian language is from the 15th century AD. The earliest reference to a Lingua Albanesca is from a 1285 document of Ragusa. This is a time when Albanian Principalities start to be mentioned and expand inside and outside the Byzantine Empire. It is assumed that Greek and Balkan Latin (which was the ancestor of Romanian and other Balkan Romance languages), would exert a great influence on Albanian. Examples of words borrowed from Latin: qytet < civitas (city), qiell < caelum (sky), mik < amicus (friend).

After the Slavs arrived in the Balkans, another source of Albanian vocabulary were the Slavic languages, especially Bulgarian. The rise of the Ottoman Empire meant an influx of Turkish words; this also entailed the borrowing of Persian and Arabic words through Turkish. Surprisingly the Persian words seem to have been absorbed the most. Some loanwords from Modern Greek also exist especially in the south of Albania. A lot of the loaned words have been resubstituted from Albanian rooted words or modern Latinized (international) words.

Writing system

- Full article: Albanian alphabet

Albanian has been written using many different alphabets since the 15th century. The earliest written Albanian records come from the Gheg area in makeshift spellings based on Italian or Greek and sometimes in Turko-Arabic characters. Originally, the Tosk dialect was written in the Greek alphabet and the Gheg dialect was written in the Latin alphabet. They have both also been written in the Ottoman Turkish version of the Arabic alphabet, the Cyrillic alphabet, and some local alphabets.

In 1908 an official, standardized Albanian spelling was developed, based on a Gheg dialect and using the Latin alphabet with the addition of the letters ë, ç, and nine digraphs. After World War II the official language changed in that it adopted the Tosk dialect as its model.

History

Linguistic affinities

The Albanian language is a distinct Indo-European language that does not belong to any other existing branch. Sharing lexical isoglosses with Greek, Balto-Slavic, and Germanic, the word stock of Albanian is quite distinct. Hastily tied to Germanic and Balto-Slavic by the merger of PIE *ǒ and *ǎ into *ǎ in a supposed "northern group",[11] Albanian has proven to be distinct from the other two groups as this vowel shift is only part of a larger push chain that affected all long vowels.[12] Albanian does share with Balto-Slavic two features: a lengthening of syllabic consonants before voiced obstruents and a distinct treatment of long syllables ending in a sonorant.[13] However, Albanian is best known for its singular conservatism, having retained the distinction between active and middle voice, present and aorist, three series of tectal consonants before front vowels (e.g., palatals, velars, and labio-velars), and initial PIE *h4 as an h.[14]

Other linguists link Albanian with Greek and Armenian in a southern group.[5][6][7]

Albanian is considered to have its closest linguistic affinity to and to have evolved from an extinct Paleo-Balkan language, usually taken to be either Illyrian or Dacian. See also Thraco-Illyrian and Messapian language.

Historical presence and location

The origin of the ethnonym Albanian is of some dispute. It appears for the first time in the 2nd c. AD in Late Greek as Albanoí (later Byz Gk Arbanitai) and thereafter in similar forms, including obsolete Albanian arbër/arbën "Albanian"; however, these last two stem directly from Vulgar Latin *Albanus, most likely borrowed from Greek Albanoí; the adjective too, arbëresh/arbënesh, are derived from Latin albanensis. This same name appears in Slavic and was used to name the town of Labëri "Laberia", from South Slavic labanĭja, from earlier *olbanĭja.

While it is considered established that the Albanians originated in the Balkans, the exact location from which they spread out is hard to pinpoint. Despite varied claims, it seems that the Albanians came from slightly farther north (Kosovo) and inland (Northwest Skopje) than would suggest the present borders of Albania, with a homeland concentrated in the mountains. The purely linguistic reasons are listed below.

- First, Albanian has few early Greek borrowings, most of which are from the Northwest dialect, probably via the islands off the coast of Albania, e.g. WGk (Doric) mākhaná gave Alb mokër "mill" and WGk drápanon gave Alb drapër "sickle".

- Similarly, the Illyrian coast is not a likely source since Albanian has no inherited nautical or indigenous seafaring terminology, and has instead supplemented this absence with subsequent borrowing from Latin or Greek or recent metaphorical lexical creations.

- Third, toponyms along the coast, in contrast with native penultimate accent (ex: mbësë "niece" < PA nepō'tia), often show substratal antepenultimate accent (ex: Durrës < Dúrrhachium; Pojanë < Apóllonia), though there are some exceptions (Vlorë < Aulónā vs. Greek Aúlon).

- Also, some consider Albanian to be the source for a small number of grammatical and lexical similarities shared by otherwise dissimilar languages including Romanian, Bulgarian, Serbo-Croatian, and to some extent Greek. Based on their extent of grammaticalization, these include: the postposition of articles, the presence and grammatical use of schwa, object reduplication, admirative through verbal constructions, and the loss of infinitives.

- Finally, few if any Proto-Albanian place names exist in what was the former Roman province of Illyria.

Instead, given the overwhelming amount of shepherding and mountaineering vocabulary as well as the extensive influence of Latin, it is more likely the Albanians come from north of the Jireček Line, on the Latin-speaking side, perhaps in part from the late Roman province of Dardania from the western Balkans. However, archaeology has more convincingly pointed to the early Byzantine province of Praevitana (modern northern Albania) which shows an area where a primarily shepherding, transhumance population of Illyrians retained their culture. This area was based in the Mat district and the region of high mountains in Northern Albania, as well as in Dukagjin, Mirditë, and the mountains of Drin, from where the population would descend in the summer to the lowlands of western Albania, the Black Drin (Drin i zi) river valley, and into parts of Old Serbia. Indeed, the region's complete lack of Latin place names seems to imply little latinization of any kind and a more likely spot for the early medieval heart of Albanian territory, following the collapse of the Illyrian province.

Linguistic influences

The period during which Proto-Albanian and Latin interacted was protracted and drawn out over six centuries, 1st c. AD to 6th or 7th c. AD. This is born out into roughly three layers of borrowings, the largest number belonging to the second layer. The first, with the fewest borrowings, was a time of less important interaction. The final period, probably preceding the Slavic or Germanic invasions, also has a notably smaller amount of borrowings. Each layer is characterized by a different treatment of most vowels, the first layer having several that follow the evolution of Early Proto-Albanian into Albanian; later layers reflect vowel changes endemic to Late Latin and presumably Proto-Romance. Other formative changes include the syncretism of several noun case endings, especially in the plural, as well as a large scale palatalization.

A brief period followed, between 7th c. AD and 9th c. AD, that was marked by heavy borrowings from Southern Slavic, some of which predate the "o-a" shift common to the modern forms of this language group. Starting in the latter 9th c. AD, a period followed characterized by protracted contact with the Proto-Romanians, or Vlachs, though lexical borrowing seems to have been mostly one sided - from Albanian into Romanian. Such borrowing indicates that the Romanians migrated from an area where the majority was Slavic (i.e. Middle Bulgarian) to an area with a majority of Albanian speakers, i.e. Dardania, where Vlachs are recorded in the 10th c. AD. Their movement is probably related to the expansion of the Bulgarian empire into Albania around that time. This fact places the Albanians at a rather early date in the western or central Balkans.

Historical considerations

Indeed, the center of the Albanians remained the river Mat, and in 1079 AD they are recorded in the territory between Ohrid and Thessalonika as well as in Epirus.

Furthermore, the major Tosk-Gheg dialect division is based on the course of the Shkumbin River, a seasonal stream that lay near the old Via Egnatia. Since rhotacism postdates the dialect division, it is reasonable that the major dialect division occurred after the Christianization of the Roman Empire (4th c. AD) and before the eclipse of the East-West land-based trade route by Venetian seapower (10th c. AD).

References to the existence of Albanian as a distinct language survive from the 1300s, but without recording any specific words. The oldest surviving documents written in Albanian are the "Formula e Pagëzimit" (Baptismal formula), "Un'te paghesont' pr'emenit t'Atit e t'Birit e t'Spirit Senit." (I baptize thee in the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit) recorded by Pal Engjelli, Bishop of Durrës in 1462 in the Gheg dialect, and some New Testament verses from that period.

The oldest known Albanian printed book, Meshari or missal, was written by Gjon Buzuku, a Roman Catholic cleric, in 1555. The first Albanian school is believed to have been opened by Franciscans in 1638 in Pdhanë. In 1635, Frang Bardhi wrote the first Latin-Albanian dictionary.

See also

- Albanian Wikipedia

- Arvanitika

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Gheg 2,779,246 + Tosk 2,980,000 + Arbereshe 80,000 + Arvanitika 150,000 = 5,989,246. (Ethnologue, 2005)

Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/. - ↑ Of the Albanian Language - William Martin Leake, London, 1814.

- ↑ ANCIENT ALBANIA INHABITED BY ILLYRIANS-Chapter 36 : Turmoil In The Balkans - Romania, Bulgaria, Albania and Greece Part Three - Albania

- ↑ "The Thracian language". The Linguist List. Retrieved on 2008-01-27. "An ancient language of Southern Balkans, belonging to the Satem group of Indo-European. This language is the most likely ancestor of modern Albanian (which is also a Satem language), though the evidence is scanty. 1st Millennium BC - 500 AD."

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 [1] Mallory, J. P. and Adams, D. Q.: The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 [2] Holm, Hans J.: The Distribution of Data in Word Lists and its Impact on the Subgrouping of Languages. In: Christine Preisach, Hans Burkhardt, Lars Schmidt-Thieme, Reinhold Decker (eds.): Data Analysis, Machine Learning, and Applications. Proc. of the 31th Annual Conference of the German Classification Society (GfKl), University of Freiburg, March 7-9, 2007. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg-Berlin

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 [3] A possible Homeland of the Indo-European Languages And their Migrations in the Light of the Separation Level Recovery (SLRD) Method - Hans J. Holm

- ↑ Gjinari, Jorgji. Dialektologjia shqiptare

- ↑ Vladimir Orel (2000) links the word to an unattested Vulgar Latin *melettum, which must be a borrowing from NW Greek mélitta. There is no real reason to posit Vulgar Latin mediation. J.P. Mallory and D.Q. Adams (1997) have the word as a native development, from *melítiā, a form also considered to underly Greek mélissa; however, this form gave Albanian mjalcë "bee", which is a native word and derivative of mjaltë "honey" (< Proto-Albanian *melita). In any case, the word does not appear to be native to Albanian.

- ↑ The word fat has both the meaning of "fate, luck" and "groom, husband". This may indicate two separate words that are homophones, one derived from Gothic and the other from Latin fātum; although, Orel (2000) sees them as the same word. Similarly, compare Albanian shortë "fate; spouse, wife" which mirrors the dichotomy in meaning of fat but is considered to stem from one single source - Latin sortem "fate".

- ↑ Calvert Watkins, "The Indo-European Linguistic Family: Genetic and Typological Perspectives", in Anna Giacalone Ramat and Paolo Ramat, eds., The Indo-European Languages (London: Routledge, 1998) 38.

- ↑ William Labov, Principles of Linguistic Change, vol. 1: Internal Factors (Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1994) 42.

- ↑ E.P. Hamp, "Albanian", in Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (Oxford, UK: Persamon Press, 1994) 66-7.

- ↑ J.P. Mallory and D.Q. Adams, "Albanian", in Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture (London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997) 9.

Bibliography

- Encyclopædia Britannica, edition 15 (1985). Article: Albanian language

- Gjinari, Jordji. Dialektologjia shqiptare. Prishtina: Universiteti, 1970.

- Huld, Martin E. Basic Albanian Etymologies. Columbus, OH: Slavica Publishers, 1984.

- Mallory, J.P. and D.Q. Adams, Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997.

- Martin Camaj, Albanian Grammar, Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden

- Orel, Vladimir. A Concise Historical Grammar of the Albanian Language: Reconstruction of Proto-Albanian. Leiden: Brill, 2000.

- Xhelal Ylli, Andrej N. Sobolev, Albanskii toskskii govor sela Leshnja. Muenchen: Biblion Verlag, 2002. ISBN 3-932331-29-X

- Xhelal Ylli, Andrej N. Sobolev, Albanskii gegskii govor sela Muhurr. Muenchen: Biblion Verlag, 2003. ISBN 3-932331-36-2

External links

- Learn Albanian

- Albanian Grammar

- Ethnologue report on Albanian

- Modern Greek and Albanian with Japanese translation

- The Albanian language - overview

- Thracian the Albanian language

Samples of various Albanian dialects:

Dictionaries:

Keyboard layouts:

- Prektora 1 ISO-8859-1 standardized layout for Windows XP (Albanian language)