Ad hominem

An ad hominem argument, also known as argumentum ad hominem (Latin: "argument to the man", "argument against the man") consists of replying to an argument or factual claim by attacking or appealing to a characteristic or belief of the person making the argument or claim, rather than by addressing the substance of the argument or producing evidence against the claim. The process of proving or disproving the claim is thereby subverted, and the argumentum ad hominem works to change the subject.

Contents |

Background

Ad hominem argument is most commonly used to refer specifically to the ad hominem as abusive, sexist, racist, or argumentum ad personam, which consists of criticizing or attacking the person who proposed the argument (personal attack) in an attempt to discredit the argument. It is also used when an opponent is unable to find fault with an argument, yet for various reasons, the opponent disagrees with it.

Other common subtypes of the ad hominem include the ad hominem circumstantial, or ad hominem circumstantiae, an attack which is directed at the circumstances or situation of the arguer; and the ad hominem tu quoque, which objects to an argument by characterizing the arguer as acting or arguing in accordance with the view that he is arguing against.

Ad hominem arguments are always invalid in syllogistic logic, since the truth value of premises is taken as given, and the validity of a logical inference is independent of the person making the inference. However, ad hominem arguments are rarely presented as formal syllogisms, and their assessment lies in the domain of informal logic and the theory of evidence.[1] The theory of evidence depends to a large degree on assessments of the credibility of witnesses, including eyewitness evidence and expert witness evidence. Evidence that a purported eyewitness is unreliable, or has a motive for lying, or that a purported expert witness lacks the claimed expertise can play a major role in making judgements from evidence.

Argumentum ad hominem is the inverse of argumentum ad verecundiam, in which the arguer bases the truth value of an assertion on the authority, knowledge or position of the person asserting it. Hence, while an ad hominem argument may make an assertion less compelling, by showing that the person making the assertion does not have the authority, knowledge or position they claim, or has made mistaken assertions on similar topics in the past, it cannot provide an infallible counterargument.

An ad hominem fallacy is a genetic fallacy and red herring, and is most often (but not always) an appeal to emotion.

It does not include arguments posed by a person that contradict the person's actions.

Ad hominem as informal fallacy

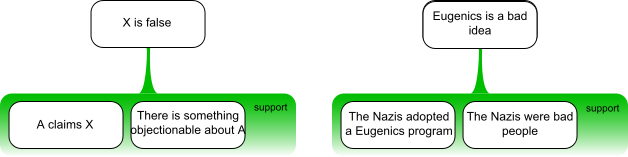

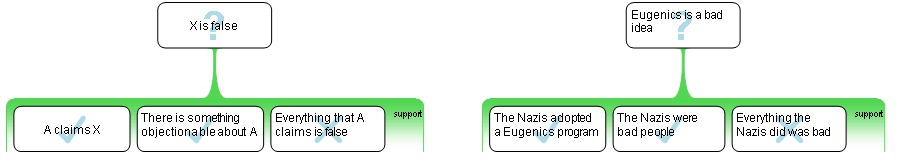

A (fallacious) ad hominem argument has the basic form:

- Person A makes claim X

- There is something objectionable about Person A

- Therefore claim X is false

Ad hominem is one of the best known of the logical and systematic fallacies usually enumerated in introductory logic and critical thinking textbooks. Both the fallacy itself, and accusations of having committed it, are often brandished in actual discourse (see also Argument from fallacy). As a technique of rhetoric, it is powerful and used often because of the natural inclination of the human brain to recognize patterns.

The first premise is called a 'factual claim' and is the pivot point of much debate. The contention is referred to as an 'inferential claim' and represents the reasoning process. There are two types of inferential claim, explicit and implicit. The fallacy does not represent a valid form of reasoning because even if you accept both co-premises, that does not guarantee the truthfulness of the contention. This can also be thought of as the argument having an un-stated co-premise.

In this example, the un-stated co-premise "everything that A claims is false" has been included, and the argument is therefore now a valid one. However in the ad hominem fallacy the un-stated co-premise is always false, thereby maintaining the fallacy. Note that this does not imply that the contention "eugenics is a bad idea" is false, merely un-supported by the pattern of reasoning below it.

Usage

In logic

An ad hominem fallacy consists of asserting that someone's argument is wrong and/or he is wrong to argue at all purely because of something discreditable/not-authoritative about the person or those persons cited by him rather than addressing the soundness of the argument itself. The implication is that the person's argument and/or ability to argue correctly lacks authority. Merely insulting another person in the middle of otherwise rational discourse does not necessarily constitute an ad hominem fallacy (though it is not usually regarded as acceptable). It must be clear that the purpose of the characterization is to discredit the person offering the argument, and, specifically, to invite others to discount his arguments. In the past, the term ad hominem was sometimes used more literally, to describe an argument that was based on an individual, or to describe any personal attack. However, this is not how the meaning of the term is typically introduced in modern logic and rhetoric textbooks, and logicians and rhetoricians are in agreement that this use is incorrect.[2]

Example:

- "You claim that this man is innocent, but you cannot be trusted since you are a criminal as well."

This argument would generally be accepted as reasonable, as regards personal evidence, on the premise that criminals are likely to lie to protect each other. On the other hand, it is a valid example of ad hominem if the person making the claim is doing so on the basis of evidence independent of their own credibility.

In general, ad hominem criticism of evidence cannot prove the negative of the proposition being claimed:

Example:

- "Paula says the umpire made the correct call, but this can't be true, because Paula wasn't even watching the game."

Assuming the premise is correct, Paula's evidence is valueless, but the umpire may nonetheless have made the right call.

Colloquially

In common language, any personal attack, regardless of whether it is part of an argument, is often referred to as ad hominem.[3]

Types of ad hominems

Three traditionally identified varieties are ad hominem abusive (or ad personam), ad hominem circumstantial, and ad hominem tu quoque.

Ad hominem abusive

Ad hominem abusive (also called argumentum ad personam) usually and most notoriously involves insulting or belittling one's opponent, but can also involve pointing out factual but ostensibly damning character flaws or actions which are irrelevant to the opponent's argument. This tactic is logically fallacious because insults and even true negative facts about the opponent's personal character have nothing to do with the logical merits of the opponent's arguments or assertions. This tactic is frequently employed as a propaganda tool among politicians who are attempting to influence the voter base in their favor through an appeal to emotion rather than by logical means, especially when their own position is logically weaker than their opponent's.

Examples:

- "You can't believe Jack when he says there is a God because he doesn't even have a job."

- "Candidate Jane Jones's proposal X is ridiculous. She was caught cheating on her taxes in 2003."

Ad hominem circumstantial

Ad hominem circumstantial involves pointing out that someone is in circumstances such that he is disposed to take a particular position. Essentially, ad hominem circumstantial constitutes an attack on the bias of a person. The reason that this is fallacious in syllogistic logic is that pointing out that one's opponent is disposed to make a certain argument does not make the argument, from a logical point of view, any less credible; this overlaps with the genetic fallacy (an argument that a claim is incorrect due to its source).

On the other hand, where the person taking a position seeks to convince us by a claim of authority, or personal observation, observation of their circumstances may reduce the evidentiary weight of the claims, sometimes to zero.[4]

Examples:

- "Tobacco company representatives should not be believed when they say smoking doesn't seriously affect your health, because they're just defending their own multi-million-dollar financial interests."

- "He's physically addicted to nicotine. Of course he defends smoking!”

- "What do you know about politics? You're too young to vote!"

Mandy Rice-Davies's famous testimony, during the Profumo Affair, "Well, he would [say that], wouldn't he?", is an example of a valid circumstantial argument. Her point is that since a man in a prominent position, accused of an affair with a callgirl, would deny the claim whether it was true or false, his denial, in itself, carries little evidential weight against the claim of an affair. Note, however, that this argument is valid only insofar as it devalues the denial; it does not bolster the original claim. To construe evidentiary invalidation of the denial as evidentiary validation of the original claim is fallacious (on several different bases, including that of argumentum ad hominem); however likely the man in question would be to deny an affair that did in fact happen, he could only be more likely to deny an affair that never did.

Ad hominem tu quoque

Ad hominem tu quoque (lit: Also to you!) refers to a claim that the person making the argument has spoken or acted in a way inconsistent with the argument. In particular, if person A criticises the actions of person B, a tu quoque response is that A has acted in the same way.

Examples:

- "You say that stealing is wrong, but you do it as well."

- "He says we shouldn't enslave people, yet he himself owns slaves"

Guilt by association

Guilt by association can sometimes also be a type of ad hominem fallacy, if the argument attacks a person because of the similarity between the views of someone making an argument and other proponents of the argument.

This form of the argument is as follows:

- Person A makes claim P.

- Group B also make claim P.

- Therefore, person A is a member of group B.

Example:

- "You say the gap between the rich and poor is unacceptable, but communists also say this, therefore you are a communist"

This fallacy can also take another form:

- Person A makes claim P.

- Group B make claims P and Q

- Therefore, Person A makes claim Q.

Examples:

- "You say the gap between the rich and poor is unacceptable, but communists also say this, and they believe in revolution. Thus, you believe in revolution."

A similar tactic may be employed to encourage someone to renounce an opinion, or force them to choose between renouncing an opinion or admitting membership in a group. For example:

- "You say the gap between the rich and poor is unacceptable. You don't really mean that, do you? Communists say the same thing. You're not a communist, are you?"

Guilt by association may be combined with ad hominem abusive. For example:

- "You say the gap between the rich and poor is unacceptable, but communists also say this, and therefore you are a communist. Communists are unlikeable, and therefore everything they say is false, and therefore everything you say is false."

A reductio ad Hitlerum argument can be seen as an example of a "guilt by association" fallacy, since it attacks a viewpoint simply because it was supposedly espoused by Adolf Hitler, as if it is impossible that such a man could have held any viewpoint that is correct.

Inverse ad hominem

An inverse ad hominem argument praises a person in order to add support for that person's argument or claim. A fallacious inverse ad hominem argument may go something like this:

- "That man was smartly-dressed and charming, so I'll accept his argument that I should vote for him"

As with regular ad hominem arguments, not all cases of inverse ad hominem are fallacious. Consider the following:

- "Elizabeth has never told a lie in her entire life, and she says she saw him take the bag. She must be telling the truth."

Here the arguer is not suggesting we accept Elizabeth's argument, but her testimony. Her being an honest person is relevant to the truth of the conclusion (that he took the bag), just as her having bad eyesight (a regular case of ad hominem) would give reason not to believe her. However, the last part of the argument is false even if the premise is true, since having never told a lie before does not mean she isn't now.

Appeal to authority is a type of inverse ad hominem argument.

See also

- Ad feminam

- "And you are lynching Negroes"

- Association fallacy

- Fair game (Scientology)

- Fundamental attribution error

- Shooting the messenger

References

- ↑ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1996). "Example: Ad Hominem". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved on September 10, 2007.

- ↑ Swift (2007). "Syvia Browne on the Ropes". Swift - Weekly Newsletter of the James Randi Educational Foundation. Retrieved on September 10, 2007.

- ↑ Bartleby.com (2007). "ad hominem". Bartleby.com. Retrieved on September 10, 2007.

- ↑ fallacyfiles.org (2007). "Argumentum ad Hominem". fallacyfiles.org. Retrieved on September 10, 2007.

Sources

- Hurley, Patrick (2000). A Concise Introduction to Logic, Seventh Edition. Wadsworth, a division of Thompson Learning. pp. 125–128, 182. ISBN 0534520065.

- Copi, Irving M. and Cohen, Carl. Introduction to Logic (8th Ed.), p. 97-100.

Further reading

- Walton, Douglas (1998). Ad Hominem Arguments. Tuscaloosa: University Alabama Press. pp. 240 pp.

External links

- Nizkor.org: Fallacy: Ad Hominem.

- Nizkor.org: Fallacy: Circumstantial Ad Hominem.

- Argumentum Ad Hominem

- the ad hominem fallacy fallacy

- University of Winnipeg: Argumentation Schemes and Historical Origins of the Circumstantial Ad Hominen ArgumentPDF (70.2 KB)

- About.com: Argument Against the Person (Argumentum ad hominem)

- Logical Fallacies: Ad Hominem

- Infidels.org: Logic and Fallacies: Constructing a Logical Argument (Argumentum ad Hominem)

- theness.org: The New England Skeptical Society: How to Argue

- Mission Critical: Introduction to Ad Hominem Fallacies

|

||||||||||||||