Acute pancreatitis

| Acute pancreatitis Classification and external resources |

|

|

|

|---|---|

| Pancreas | |

| ICD-10 | K85. |

| ICD-9 | 577.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 9539 |

| MedlinePlus | 000287 |

| eMedicine | med/1720 radio/521 |

Acute pancreatitis is a sudden inflammation of the pancreas. Depending on its severity, it can have severe complications and high mortality despite treatment. While mild cases are often successfully treated with conservative measures, such as NPO (abstaining from any oral intake) and IV fluid rehydration, severe cases may require admission to the ICU or even surgery (often more than one intervention) to deal with complications of the disease process.

Contents |

Symptoms and signs

- Severe epigastric pain radiating to the back.

- Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and loss of appetite.

- Fever/Chills

- Shock, hemodynamic instability

- Steatorrhea- pale, foul-smelling and oily stool.

Less common or signs of severe disease

- Grey Turner sign (hemorrhagic discoloration of the flanks)

- Cullen sign (hemorrhagic discoloration of the umbilicus)

Other conditions to consider

- pancreatic pseudocyst,

- pancreatic dysfunction (malabsorption due to exocrine failure) or diabetes mellitus.

- pancreatic cancer

Causes

Most common causes

The FDA reported in August, 2008 6 cases of hemorrhagic or necrotizing pancreatitis in patients taking Byetta, a diabetes medicine approved in 2005. Two patients died. The FDA previously reported 30 other cases of pancreatitis. Patients taking Byetta should promptly seek medical care if they experience unexplained severe abdominal pain with or without nausea and vomiting. [1]

A common mnemonic for the causes of pancreatitis spells "I get smashed", an allusion to heavy drinking (one of the many causes):

- I - idiopathic

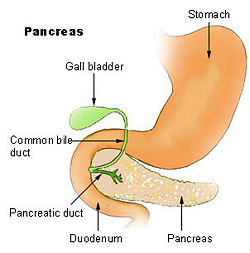

- G - gallstone. Gallstones that travel down the common bile duct and which subsequently get stuck in the Ampulla of Vater can cause obstruction in the outflow of pancreatic juices from the pancreas into the duodenum. The backflow of these digestive juices causes lysis (dissolving) of pancreatic cells and subsequent pancreatitis.

- E - ethanol (alcohol)

- T - trauma

- S - steroids

- M - mumps (paramyxovirus) and other viruses (Epstein-Barr virus, Cytomegalovirus)

- A - autoimmune disease (Polyarteritis nodosa, Systemic lupus erythematosus)

- S - scorpion sting - Tityus Trinitatis - Trinidad/ snake bite

- H - hypercalcemia, hyperlipidemia/hypertriglyceridemia and hypothermia

- E - ERCP (Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangio-Pancreatography - a procedure that combines endoscopy and fluoroscopy)

- D - drugs (SAND - steroids & sulfonamides, azathioprine, NSAIDS, diuretics such as furosemide and thiazides, & didanosine) and duodenal ulcers

Less common causes

- pancreas divisum

- long common duct

- carcinoma of the head of pancreas, and other cancer

- ascaris blocking pancreatic outflow

- chinese liver fluke

- ischemia from bypass surgery

- fatty necrosis

- pregnancy

- infections other than mumps, including varicella zoster

- repeated marathon running.

- cystic fibrosis

Causes by demographic

The most common causes of pancreatitis, are as follows :

- Western countries - chronic alcoholism and gallstones accounting for more than 85% of all cases

- Eastern countries - gallstones

- Children - trauma

- Adolescents and young adults - mumps

Pathogenesis

The exocrine pancreas produces a variety of enzymes, such as proteases, lipases, and saccharidases. These enzymes contribute to food digestion by breaking down food tissues. In acute pancreatitis, the worst offender among these enzymes may well be the protease trypsinogen which converts to the active trypsin which is most responsible for auto-digestion of the pancreas which causes the pain and complications of pancreatitis.

Histopathology The acute pancreatitis (acute hemorrhagic pancreatic necrosis) is characterized by acute inflammation and necrosis of pancreas parenchyma, focal enzymic necrosis of pancreatic fat and vessels necrosis - hemorrhage. These are produced by intrapancreatic activation of pancreatic enzymes. Lipase activation produces the necrosis of fat tissue in pancreatic interstitium and peripancreatic spaces. Necrotic fat cells appear as shadows, contours of cells, lacking the nucleus, pink, finely granular cytoplasm. It is possible to find calcium precipitates (hematoxylinophilic). Digestion of vascular walls results in thrombosis and hemorrhage. Inflammatory infiltrate is rich in neutrophils. Photos at: Atlas of Pathology

Investigations

- Blood Investigations - Full blood count, Renal function tests, Liver Function, serum calcium, serum amylase and lipase, Arterial blood gas

- Imaging - Chest Xray (for exclusion of perforated viscus), Abdominal Xrays (for detection of "sentinel loop" dilated duodenum sign, and gallstones which are radioopaque in 10%) and CT abdomen

Amylase and lipase

- Serum amylase and lipase may be used in the making of the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis.

- Serum amylase usually rises 2 to 12 hours from the onset of symptoms, and normalizes within 48-72 hours.

- Serum lipase rises 4 to 8 hours from the onset of symptoms and normalizes within 7 to 14 days.

- Serum amylase may be normal (in 10% of cases) for cases of acute on chronic pancreatitis (depleted acinar cell mass) and hypertriglyceridemia.

- Reasons for false positive elevated serum amylase include salivary gland disease (elevated salivary amylase) and macroamylasemia.

- If the lipase level is about 2.5 to 3 times that of Amylase, it is an indication of pancreatitis due to Alcohol [2].

Regarding selection on these tests, two practice guidelines state:

- "It is usually not necessary to measure both serum amylase and lipase. Serum lipase may be preferable because it remains normal in some nonpancreatic conditions that increase serum amylase including macroamylasemia, parotitis, and some carcinomas. In general, serum lipase is thought to be more sensitive and specific than serum amylase in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis" [3]

- "Although amylase is widely available and provides acceptable accuracy of diagnosis, where lipase is available it is preferred for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis (recommendation grade A)"[4]

Most (PMID 15943725, PMID 11552931, PMID 2580467, PMID 2466075, PMID 9436862), but not all (PMID 11156345, PMID 8945483) individual studies support the superiority of the lipase. In one large study, there were no patients with pancreatitis who had an elevated amylase with a normal lipase [5]. Another study found that the amylase could add diagnostic value to the lipase, but only if the results of the two tests were combined with a discriminant function equation [6].

Computed tomography

Regarding the need for computed tomography, practice guidelines state:

- 2006: "Many patients with acute pancreatitis do not require a CT scan at admission or at any time during the hospitalization. For example, a CT scan is usually not essential in patients with recurrent mild pancreatitis caused by alcohol. A reasonable indication for a CT scan at admission (but not necessarily a CT with IV contrast) is to distinguish acute pancreatitis from another serious intra-abdominal condition, such as a perforated ulcer." [3]

- 2005: "Patients with persisting organ failure, signs of sepsis, or deterioration in clinical status 6–10 days after admission will require CT (recommendation grade B)."[4]

CT abdomen should not be performed before the 1st 48 hours of onset of symptoms as early CT (<48 h) may result in equivocal or normal findings.

CT Findings can be classified into the following categories for easy recall :

- Intrapancreatic - diffuse or segmental enlargement, edema, gas bubbles, pancreatic pseudocysts and phlegmons/abscesses (which present 4 to 6 wks after initial onset)

- Peripancreatic / extrapancreatic - irregular pancreatic outline, obliterated peripancreatic fat, retroperitoneal edema, fluid in the lessar sac, fluid in the left anterior pararenal space

- Locoregional - Gerota's fascia sign (thickening of inflamed Gerota's fascia, which becomes visible), pancreatic ascites, pleural effusion (seen on basal cuts of the pleural cavity), adynamic ileus,

Balthazar scoring

Balthazar Scoring for the Grading of Acute Pancreatitis

The CT Severity Score is the sum of the CT Grade and Necrosis Grade Scores.

CT Grade Score

| CT Grade | Appearance on CT | CT Grade Points |

|---|---|---|

| Grade A | Normal CT | 0 points |

| Grade B | Focal or diffuse enlargement of the pancreas | 1 point |

| Grade C | Pancreatic gland abnormalities and peripancreatic inflammation | 2 points |

| Grade D | Fluid collection in a single location | 3 points |

| Grade E | Two or more fluid collections and / or gas bubbles in or adjacent to pancreas | 4 points |

Necrosis score

| Necrosis Percentage | Points |

|---|---|

| No necrosis | 0 points |

| 0 to 30% necrosis | 2 points |

| 30 to 50% necrosis | 4 points |

| Over 50% necrosis | 6 points |

Magnetic resonance imaging

One study found that a nonenhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was comparable to contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT).[7]

Classification by severity

Progression of pathophysiology

Acute pancreatitis can be further divided into mild and severe pancreatitis. Mostly the Atlanta classification (1992) is used. In severe pancreatitis serious amount of necrosis determine the further clinical outcome. About 20% of the acute pancreatitis are severe with a mortality of about 20%. This is an important classification as severe pancreatitis will need intensive care therapy whereas mild pancreatitis can be treated on the common ward.

Necrosis will be followed by a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and will determine the immediate clinical course. The further clinical course is then determined by bacterial infection. SIRS is the cause of bacterial (Gram negative) translocation from the patients colon.

There are several ways to help distinguish between these two forms. One is the above mentioned Ranson Score.

Prognostic indices

In predicting the prognosis, there are several scoring indices that have been used as predictors of survival. Two such scoring systems are the Ranson and APACHE II (Acute Physiology, Age and Chronic Health Evaluation) indices. Most[8] [9], but not all [10] studies report that the Apache score may be more accurate. In the negative study of the Apache II [10], the Apache II 24 hr score was used rather than the 48 hour score. In addition, all patients in the study received at ultrasound twice which may have influenced allocation of co-interventions. Regardless, only the Apache II can be fully calculated upon admission. As the Apache II is more cumbersome to calculate, presumably patients whose only laboratory abnormality is an elevated lipase or amylase do not need prognostication with the Apache II; however, this approach is not studied. The Apache II score can be calculated at www.sfar.org.

Practice guidelines state:

- 2006: "The two tests that are most helpful at admission in distinguishing mild from severe acute pancreatitis are APACHE-II score and serum hematocrit. It is recommended that APACHE-II scores be generated during the first 3 days of hospitalization and thereafter as needed to help in this distinction. It is also recommended that serum hematocrit be obtained at admission, 12 h after admission, and 24 h after admission to help gauge adequacy of fluid resuscitation."[3]

- 2005: "Immediate assessment should include clinical evaluation, particularly of any cardiovascular, respiratory, and renal compromise, body mass index, chest x ray, and APACHE II score" [4]

Ranson

APACHE

"Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation" (APACHE II) score > 8 points predicts 11% to 18% mortality [3] Online calculator

- Hemorrhagic peritoneal fluid

- Obesity

- Indicators of organ failure

- Hypotension (SBP <90 mmHG) or tachycardia > 130 beat/min

- PO2 <60 mmHg

- Oliguria (<50 mL/h) or increasing BUN and creatinine

- Serum calcium < 1.90 mmol/L (<8.0 mg/dL) or serum albumin <33 g/L (<3.2.g/dL)>

Treatment

Pain control

Originally it was thought that analgesia should not be provided by morphine because it may cause spasm of the sphincter of Oddi and worsen the pain, so the drug of choice was meperidine. However, due to lack of efficacy and risk of toxicity of meperidine, more recent studies have found morphine the analgesic of choice.

Bowel rest

In the management of acute pancreatitis, the treatment is to stop feeding the patient, giving him or her nothing by mouth, giving intravenous fluids to prevent dehydration, and sufficient pain control. As the pancreas is stimulated to secrete enzymes by the presence of food in the stomach, having no food pass through the system allows the pancreas to rest. Approximately 20% of patients have a relapse of pain during acute pancreatitis.[11] Approximately 75% of relapses occur within 48 hours of oral refeeding.

The incidence of relapse after oral refeeding may be reduced by post-pyloric enteral rather than parenteral feeding prior to oral refeeding.[11] IMRIE scoring is also useful.

Nutritional support

Recently, there has been a shift in the management paradigm from TPN (total parenteral nutrition) to early, post-pyloric enteral feeding (in which a feeding tube is endoscopically or radiographically introduced to the third portion of the duodenum). The advantage of enteral feeding is that it is more physiological, prevents gut mucosal atrophy, and is free from the side effects of TPN (such as fungemia). The additional advantages of post-pyloric feeding are the inverse relationship of pancreatic exocrine secretions and distance of nutrient delivery from the pylorus, as well as reduced risk of aspiration.

Disadvantages of a naso-enteric feeding tube include increased risk of sinusitis (especially if the tube remains in place greater than two weeks) and a still-present risk of accidentally intubating the bronchus even in intubated patients (contrary to popular belief, the endotracheal tube cuff alone is not always sufficient to prevent NG tube entry into the trachea).

Antibiotics

A meta-analysis by the Cochrane Collaboration concluded that antibiotics help with a number needed to treat of 11 patients to reduce mortality [12]. However, the one study in the meta-analysis that used a quinolone, and a subsequent randomized controlled trial that studied ciprofloxacin were both negative [13].

Carbapenems

An early randomized controlled trial of imipenem 0.5 gram intravenously every eight hours for two weeks showed a reduction in from pancreatic sepsis from 30% to 12%. [14]

Another randomized controlled trial with patients who had at least 50% pancreatic necrosis found a benefit from imipenem compared to pefloxacin with a reduction in infected necrosis from 34% to 20%[15]

A subsequent randomized controlled trial that used meropenem 1 gram intravenously every 8 hours for 7 to 21 days stated no benefit; however, 28% of patients in the group subsequently required open antibiotic treatment vs. 46% in the placebo group. In addition, the control group had only 18% incidence of peripancreatic infections and less biliary pancreatitis that the treatment group (44% versus 24%).[16]

Summary

In summary, the role of antibiotics is controversial. One recent expert opinion (prior to the last negative trial of meropenem[16]) suggested the use of imipenem if CT scan showed more than 30% necrosis of the pancreas.[17]

ERCP

Early ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography), performed within 24 to 72 hours of presentation, is known to reduce morbidity and mortality.[18] The indications for early ERCP are as follows :

- Clinical deterioration or lack of improvement after 24 hours

- Detection of common bile duct stones or dilated intrahepatic or extrahepatic ducts on CT abdomen

The disadvantages of ERCP are as follows :

- ERCP precipitates pancreatitis, and can introduce infection to sterile pancreatitis

- The inherent risks of ERCP i.e. bleeding

It is worth noting that ERCP itself can be a cause of pancreatitis.

Surgery

Surgery is indicated for (i) infected pancreatic necrosis and (ii) diagnostic uncertainty and (iii)complications. The most common cause of death in acute pancreatitis is secondary infection. Infection is diagnosed based on 2 criteria

- Gas bubbles on CT scan (present in 20 to 50% of infected necrosis)

- Positive bacterial culture on FNA (fine needle aspiration, usually CT or US guided) of the pancreas.

Surgical options for infected necrosis include:

- Minimally invasive management - necrosectomy through small incision in skin (left flank) or stomach

- Conventional management - necrosectomy with simple drainage

- Closed management - necrosectomy with closed continuous postoperative lavage

- Open management - necrosectomy with planned staged reoperations at definite intervals (up to 20+ reoperations in some cases)

Other measures

- Pancreatic enzyme inhibitors are not proven to work.[19]

- The use of octreotide has not been shown to improve outcome.[20]

Complications

Complications can be systemic or locoregional.

- Systemic complications include ARDS, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, DIC, hypocalcemia (from fat saponification), hyperglycemia and insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (from pancreatic insulin producing beta cell damage)

- Locoregional complications include pancreatic pseudocyst and phlegmon / abscess formation, splenic artery pseudoaneurysms, hemorrhage from erosions into splenic artery and vein, thrombosis of the splenic vein, superior mesenteric vein and portal veins (in descending order of frequency), duodenal obstruction, common bile duct obstruction, progression to chronic pancreatitis

Epidemiology

- Annual incidence in the U.S. is 18 per 100,000 population. In a European cross-sectional study, incidence of acute pancreatits increased from 12.4 to 15.9 per 100,000 annually from 1985 to 1995; however, mortality remained stable as a result of better outcomes.[21] Another study showed a lower incidence of 9.8 per 100,000 but a similar worsening trend (increasing from 4.9 in 1963-74) over time.[22]

See also

- Chronic pancreatitis

References

- ↑ http://www.fda.gov/CDER/Drug/InfoSheets/HCP/exenatide2008HCP.htm

- ↑ Gumaste V, Dave P, Weissman D, Messer J (1991). "Lipase/amylase ratio. A new index that distinguishes acute episodes of alcoholic from nonalcoholic acute pancreatitis". Gastroenterology 101 (5): 1361–6. PMID 1718808.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Banks P, Freeman M (2006). "Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis". Am J Gastroenterol 101 (10): 2379–400. doi:. PMID 17032204.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 UK Working Party on Acute Pancreatitis (2005). "UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis". Gut 54 Suppl 3: iii1. doi:. PMID 15831893. http://gut.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/54/suppl_3/iii1.

- ↑ Smith R, Southwell-Keely J, Chesher D (2005). "Should serum pancreatic lipase replace serum amylase as a biomarker of acute pancreatitis?". ANZ J Surg 75 (6): 399–404. doi:. PMID 15943725.

- ↑ Corsetti J, Cox C, Schulz T, Arvan D (1993). "Combined serum amylase and lipase determinations for diagnosis of suspected acute pancreatitis". Clin Chem 39 (12): 2495–9. PMID 7504593.

- ↑ Stimac D, Miletić D, Radić M, et al (2007). "The role of nonenhanced magnetic resonance imaging in the early assessment of acute pancreatitis". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 102 (5): 997–1004. doi:. PMID 17378903.

- ↑ Larvin M, McMahon M (1989). "APACHE-II score for assessment and monitoring of acute pancreatitis". Lancet 2 (8656): 201–5. doi:. PMID 2568529.

- ↑ Yeung Y, Lam B, Yip A (2006). "APACHE system is better than Ranson system in the prediction of severity of acute pancreatitis". Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 5 (2): 294–9. PMID 16698595. http://www.hbpdint.com/text.asp?id=837.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Chatzicostas C, Roussomoustakaki M, Vlachonikolis I, Notas G, Mouzas I, Samonakis D, Kouroumalis E (2002). "Comparison of Ranson, APACHE II and APACHE III scoring systems in acute pancreatitis". Pancreas 25 (4): 331–5. doi:. PMID 12409825 (comment=this study used a Apache cutoff of >=10).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Petrov MS, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Cirkel GA, Brink MA, Gooszen HG (2007). "Oral Refeeding After Onset of Acute Pancreatitis: A Review of Literature". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 102: 2079. doi:. PMID 17573797.

- ↑ Villatoro E, Bassi C, Larvin M (2006). "Antibiotic therapy for prophylaxis against infection of pancreatic necrosis in acute pancreatitis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD002941. doi:. PMID 17054156.

- ↑ Isenmann R, Rünzi M, Kron M, Kahl S, Kraus D, Jung N, Maier L, Malfertheiner P, Goebell H, Beger H (2004). "Prophylactic antibiotic treatment in patients with predicted severe acute pancreatitis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial". Gastroenterology 126 (4): 997–1004. doi:. PMID 15057739.

- ↑ Pederzoli P, Bassi C, Vesentini S, Campedelli A (1993). "A randomized multicenter clinical trial of antibiotic prophylaxis of septic complications in acute necrotizing pancreatitis with imipenem". Surgery, gynecology & obstetrics 176 (5): 480–3. PMID 8480272.

- ↑ Bassi C, Falconi M, Talamini G, et al (1998). "Controlled clinical trial of pefloxacin versus imipenem in severe acute pancreatitis". Gastroenterology 115 (6): 1513–7. doi:. PMID 9834279.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Dellinger EP, Tellado JM, Soto NE, et al (2007). "Early antibiotic treatment for severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". Ann. Surg. 245 (5): 674–83. doi:. PMID 17457158.

- ↑ Whitcomb D (2006). "Clinical practice. Acute pancreatitis". N Engl J Med 354 (20): 2142–50. doi:. PMID 16707751. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/354/20/2142.

- ↑ Apostolakos, Michael J.; Peter J. Papadakos (2001). The Intensive Care Manual. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0070066965.

- ↑ DeCherney, Alan H.; Lauren Nathan (2003). Current Obstetric & Gynecologic Diagnosis & Treatment. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0838514014.

- ↑ Peitzman, Andrew B.; C. William Schwab, Donald M. Yealy, Timothy C. Fabian (2007). The Trauma Manual: Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0781762758.

- ↑ Eland IA, Sturkenboom MJ, Wilson JH, Stricker BH (2000). "Incidence and mortality of acute pancreatitis between 1985 and 1995". Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 35 (10): 1110–6. PMID 11099067.

- ↑ Goldacre MJ, Roberts SE (2004). "Hospital admission for acute pancreatitis in an English population, 1963-98: database study of incidence and mortality". BMJ 328 (7454): 1466–9. doi:. PMID 15205290.

External links

- VIDEO: Complications of Acute Pancreatitis: Management and Outcomes, Mark Malangoni, MD, speaks at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health (2007)

- Medical Information and Treatment of Acute Pancreatitis

- Mechanisms of Disease: Etiology and Pathophysiology of Acute Pancreatitis

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||