Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia Classification and external resources |

|

|

|

|---|---|

| ICD-10 | C91.0 |

| ICD-9 | 204.0 |

| ICD-O: | 9821/3 |

| DiseasesDB | 195 |

| eMedicine | med/3146 ped/2587 |

| MeSH | D054198 |

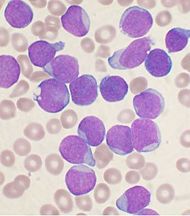

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), is a form of leukemia, or cancer of the white blood cells.

Malignant, immature white blood cells continuously multiply and are overproduced in the bone marrow. ALL causes damage and death by crowding out normal cells in the bone marrow, and by spreading (metastasizing) to other organs. ALL is most common in childhood and young adulthood with a peak incidence at 4-5 years of age, and another peak in old age. The overall cure rate in children is 85%, and about 50% of adults have long-term disease-free survival.[1] 'Acute' refers to the undifferentiated, immature state of the circulating lymphocytes ("blasts"), and to the rapid progression of disease, which can be fatal in weeks to months if left untreated.

Contents |

Symptoms

Initial symptoms are not specific to ALL, but worsen to the point that medical help is sought. The signs and symptoms of ALL are variable but follow from bone marrow replacement and/or organ infiltration.

- Generalised weakness and fatigue

- Anemia

- Frequent or unexplained fever and infections

- Weight loss and/or loss of appetite

- Excessive and unexplained bruising

- Bone pain, joint pains (caused by the spread of "blast" cells to the surface of the bone or into the joint from the marrow cavity)

- Breathlessness

- Enlarged lymph nodes, liver and/or spleen

- Pitting edema (swelling) in the lower limbs and/or abdomen

- Petechiae, which are tiny red spots or lines in the skin due to low platelet levels

The signs and symptoms of ALL result from the lack of normal and healthy blood cells because they are crowded out by malignant and immature leukocytes (white blood cells). Therefore, people with ALL experience symptoms from malfunctioning of their erythrocytes (red blood cells), leukocytes, and platelets not functioning properly. Laboratory tests which might show abnormalities include blood count tests, renal function tests, electrolyte tests and liver enzyme tests.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing ALL begins with a medical history and physical examination, complete blood count, and blood smears. Because the symptoms are so general, many other diseases with similar symptoms must be excluded. Typically, the higher the white blood cell count, the worse the prognosis. [2] Blast cells are seen on blood smear in 90% of cases. A bone marrow biopsy is conclusive proof of ALL.[3] A spinal tap will tell if the spinal column and brain has been invaded.

Pathological examination, cytogenetics (particularly the presence of Philadelphia chromosome) and immunophenotyping, establish whether the "blast" cells began from the B lymphocytes or T lymphocytes. DNA testing can establish how aggressive the disease is; different mutations have been associated with shorter or longer survival.

Medical imaging (such as ultrasound or CT scanning) can find invasion of other organs commonly the lung, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, brain, kidneys and reproductive organs.

Pathophysiology

The cause of most ALL is not known. In general, cancer is caused by damage to DNA that leads to uncontrolled cellular growth and spread throughout the body, either by increasing chemical signals that cause growth, or interrupting chemical signals that control growth. Damage can be caused through the formation of fusion genes, as well as the dysregulation of a proto-oncogene via juxtaposition of it to the promotor of another gene, e.g. the T-cell receptor gene. This damage may be caused by environmental factors such as chemicals, drugs or radiation.

ALL is associated with exposure to radiation and chemicals in animals and humans. The association of radiation and leukemia in humans has been clearly established in studies of victims of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor and atom bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In animals, exposure to benzene and other chemicals can cause leukemia. Epidemiological studies have associated leukemia with workplace exposure to chemicals, but these studies are not as conclusive. Patients who are treated for other cancers with radiation and chemotherapy often develop leukemias as a result of that treatment.

Cytogenetics

Cytogenetic translocations associated with specific molecular genetic abnormalities in ALL

| Cytogenetic translocation | Molecular genetic abnormality |

|---|---|

| t(9;22)(q34;q11) | BCR-ABL fusion(P185) |

| t(12;21)CRYPTIC | TEL-AML1fusion |

| t(1;19)(q23;p13) | E2A-PBX fusion |

| t(4;11)(q21;q23) | MLL-AF4 fusion |

| t(8;14)(q24;q32) | IGH-MYC fusion |

| t(11;14)(p13;q11) | TCR-RBTN2 fusion |

Cytogenetics, the study of characteristic large changes in the chromosomes of cancer cells, has been increasingly recognized as an important predictor of outcome in ALL.[5]

Some cytogenetic subtypes have a worse prognosis than others. These include:

- A translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22, known as the Philadelphia chromosome, occurs in about 20% of adult and 5% in pediatric cases of ALL.

- A translocation between chromosomes 4 and 11 occurs in about 4% of cases and is most common in infants under 12 months.

- Not all translocations of chromosomes carry a poorer prognosis. Some translocations are relatively favorable. For example, Hyperdiploidy (>50 chromosomes) is a good prognostic factor.

| Cytogenetic change | Risk category |

|---|---|

| Philadelphia chromosome | Poor prognosis |

| t(4;11)(q21;q23) | Poor prognosis |

| t(8;14)(q24.1;q32) | Poor prognosis |

| Complex karyotype (more than four abnormalities) | Poor prognosis |

| Low hypodiploidy or near triploidy | Poor prognosis |

| High hyperdiploidy | Good prognosis |

| del(9p) | Good prognosis |

Classification

As ALL is not a solid tumour, the TxNxMx notation as used in solid cancers is of little use.

The FAB classification

Subtyping of the various forms of ALL used to be done according to the French-American-British (FAB) classification,[6] which was used for all acute leukemias (including acute myelogenous leukemia, AML).

- ALL-L1: small uniform cells

- ALL-L2: large varied cells

- ALL-L3: large varied cells with vacuoles (bubble-like features)

Each subtype is then further classified by determining the surface markers of the abnormal lymphocytes, called immunophenotyping. There are 2 main immunologic types: pre-B cell and pre-T cell. The mature B-cell ALL (L3) is now classified as Burkitt's lymphoma/leukemia. Subtyping helps determine the prognosis and most appropriate treatment in treating ALL.

WHO proposed classification of acute lymphoblastic leukemia

The recent WHO International panel on ALL recommends that the FAB classification be abandoned, since the morphological classification has no clinical or prognostic relevance. It instead advocates the use of the immunophenotypic classification mentioned below.

1- Acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma Synonyms:Former Fab L1/L2

- i. Precursor B acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Cytogenetic subtypes:[7]

- t(12;21)(p12,q22) TEL/AML-1

- t(1;19)(q23;p13) PBX/E2A

- t(9;22)(q34;q11) ABL/BCR

- T(V,11)(V;q23) V/MLL

- ii. Precursor T acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma

2- Burkitt's leukemia/lymphoma Synonyms:Former FAB L3

3- Biphenotypic acute leukemia

Variant Features of ALL

- 1- Acute lymphoblastic leukemia with cytoplasmic granules

- 2- Aplastic presentation of ALL

- 3- Acute lymphoblastic leukemia with eosinophilia

- 4- Relapse of lymphoblastic leukemia

- 5- Secondary AML

Immunophenotyping in the diagnosis and classification of ALL

The use of a TdT assay and a panel of monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) to T cell and B cell associated antigens will identify almost all cases of ALL.

Immunophenotypic categories of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)

| Types | FAB Class | Tdt | T cell associate antigen | B cell associate antigen | c Ig | s Ig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor B | L1,L2 | + | - | + | -/+ | - |

| Precursor T | L1,L2 | + | + | - | - | - |

| B-cell | L3 | - | - | + | - | + |

Treatment

The earlier acute lymphocytic leukemia is detected, the more effective the treatment. The aim is to induce a lasting remission, defined as the absence of detectable cancer cells in the body (usually less than 5% blast cells on the bone marrow).

Treatment for acute leukemia can include chemotherapy, steroids, radiation therapy, intensive combined treatments (including bone marrow or stem cell transplants), and growth factors.[8]

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the initial treatment of choice. Most ALL patients end up receiving a combination of different treatments. There are no surgical options, due to the body-wide distribution of the malignant cells.

In general, cytotoxic chemotherapy for ALL combines multiple antileukemic drugs in various combinations. Chemotherapy for ALL consists of three phases: remission induction, intensification, and maintenance therapy. Chemotherapy is also indicated to protect the central nervous system from leukemia. The aim of remission induction is to rapidly kill most tumor cells and get the patient into remission. This is defined as the presence of less than 5% leukemic blasts in the bone marrow, normal blood cells and absence of tumor cells from blood, and absence of other signs and symptoms of the disease. Combination of Prednisolone or dexamethasone (in children), vincristine, asparaginase, and daunorubicin (used in Adult ALL) is used to induce remission. Intensification uses high doses of intravenous multidrug chemotherapy to further reduce tumor burden. Typical intensification protocols use vincristine, cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, daunorubicin, etoposide, thioguanine or mercaptopurine given as blocks in different combinations. Since ALL cells sometimes penetrate the Central Nervous System (CNS), most protocols include delivery of chemotherapy into the CNS fluid (termed intrathecal chemotherapy). Some centers deliver the drug through Ommaya reservoir (a device surgically placed under the scalp and used to deliver drugs to the CNS fluid and to extract CNS fluid for various tests). Other centers would perform multiple lumbar punctures as needed for testing and treatment delivery. Intrathecal methotrexate or cytarabine is usually used for this purpose. The aim of maintenance therapy is to kill any residual cell that was not killed by remission induction, and intensification regimens. Although such cells are few, they will cause relapse if not eradicated. For this purpose, daily oral mercaptopurine, once weekly oral methotrexate, once monthly 5-day course of intravenous vincristine and oral corticosteroids are usually used. The length of maintenance therapy is 3 years for boys, 2 years for girls and adults. Central nervous system relapse is treated with intrathecal administration of hydrocortisone, methotrexate, and cytarabine. [9]

A newly developed study for the treatment of Acute Lymphoblastic leukemia, known as COALL 03-07 is underway in Hamburg. This new study compares chemotherapeutic regimes to discover which therapy better suits patients with ALL.

As the chemotherapy regimens can be intensive and protracted (often about 2 years in case of the GMALL UKALL, HyperCVAD or CALGB protocols; about 3 years for males on COG protocols), many patients have an intravenous catheter inserted into a large vein (termed a central venous catheter or a Hickman line), or a Portacath (a cone-shaped port with a silicone nose that is surgically planted under the skin, usually near the collar bone, and the most effective product available, due to low infection risks and the long-term viability of a portacath).

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy (or radiotherapy) is used on painful bony areas, in high disease burdens, or as part of the preparations for a bone marrow transplant (total body irradiation). Radiation in the form of whole brain radiation is also used for central nervous system prophylaxis, to prevent recurrence of leukemia in the brain. Whole brain prophylaxis radiation used to be a common method in treatment of children’s ALL. Recent studies showed that CNS chemotherapy provided results as favorable but with less developmental side effects. As a result, the use of whole brain radiation has been more limited.

Epidemiology

The number of annual ALL cases in the US is roughly 4000, 3000 of which inflict children. ALL accounts for approximately 80 percent of all childhood leukemia cases, making it the most common type of childhood cancer. It has a peak incident rate of 2-5 years old, decreasing in incidence with increasing age before increasing again at around 50 years old. ALL is slightly more common in males than females. There is an increased incidence in people with Down Syndrome, Fanconi anemia, Bloom syndrome, Ataxia telangiectasia, X-linked agammaglobulinemia and Severe combined immunodeficiency.

Prognosis

Advancements in medical technology and research over the past four decades in the treatment of ALL has improved the overall prognosis significantly from a zero to 20-75 percent survival rate, largely due to the continuous development of clinical trials and improvements in bone marrow transplantation (BMT) and stem cell transplantation (SCT) technology.

It is worth noting that medical advances in recent years, both through matching the best treatment to the genetic characteristics of the blast cells and through the availability of new drugs, are not fully reflected in statistics that usually refer to five-year survival rates. The prognosis for ALL differs between individuals depending on a wide variety of factors:

- Sex: females tend to fare better than males.

- Ethnicity: Caucasians are more likely to develop acute leukemia than African-Americans, Asians and Hispanics and tend to have a better prognosis than non-Caucasians.

- Age at diagnosis: children between 1-10 years of age are most likely to develop ALL and to be cured of it. Cases in older patients are more likely to result from chromosomal abnormalities (e.g. the Philadelphia chromosome) that make treatment more difficult and prognoses poorer.

- White blood cell count at diagnosis of less than 50,000/µl

- Whether the cancer has spread to the brain or spinal cord

- Morphological, immunological, and genetic subtypes

- Response of patient to initial treatment

- Genetic disorders such as Down's Syndrome

Correlation of prognosis with bone marrow cytogenetic finding in acute lymphoblastic leukemia

| Prognosis | Cytogenetic findings |

|---|---|

| Favorable | Hyperdiploidy > 50 ; t (12;21) |

| Intermediate | Hyperdioloidy 47 -50; Normal(diploidy); del (6q); Rearrangements of 8q24 |

| Unfavorable | Hypodiploidy-near haploidy; Near tetraploidy; del (17p); t (9;22); t (11q23) |

Additional images

References

- ↑ Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 16th Edition, Chapter 97. Malignancies of Lymphoid Cells. Clinical Features, Treatment, and Prognosis of Specific Lymphoid Malignancies.

- ↑ Collier, J.A.B (1991). Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties, Third Edition. Oxford. pp. 810. ISBN 0-19-262116-5.

- ↑ Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 16th EditioN, Chapter 97. Malignancies of Lymphoid Cells. Clinical Features, Treatment, and Prognosis of Specific Lymphoid Malignancies.

- ↑ Merck Manual

- ↑ Moorman A, Harrison C, Buck G, Richards S, Secker-Walker L, Martineau M, Vance G, Cherry A, Higgins R, Fielding A, Foroni L, Paietta E, Tallman M, Litzow M, Wiernik P, Rowe J, Goldstone A, Dewald G (2007). "Karyotype is an independent prognostic factor in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): analysis of cytogenetic data from patients treated on the Medical Research Council (MRC) UKALLXII/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 2993 trial". Blood 109 (8): 3189–97. doi:. PMID 17170120.

- ↑ "ACS :: How Is Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia Classified?".

- ↑ "Advances in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia".

- ↑ Acute lymphoblastic leukemia at Mount Sinai Hospital

- ↑ Hoffbrand AV, Moss PAH, and Pettit JE, "Essential Haematology", Blackwell, 5th ed., 2006.

See also

- Maarten van der Weijden, diagnosed with ALL in 2001, winner of the 10 km open water marathon race at the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing

External links

- Information about ALL from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society

- Information about ALL from Cancer Research UK

- Directory of children's cancer-related resources from Children's Cancer Web

- Information about ALL from the Centre for Cancer and Blood Disorders at Sydney Children’s Hospital

- Information about ALL from European LeukemiaNet

- Information on childhood ALL from ACOR's Ped-Onc Resource Center, including disease details (MRD, phenotypes, molecular characterization), a layman's list of current and past clinical trials, a collection of articles on the possible causes of ALL, a bibliography of journal articles, and links to sources of support for parents of children with ALL.

- Association of Cancer Online Resource (ACOR) Leukemia Links - provides links to information on leukemia, including ALL, primarily in adults.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||