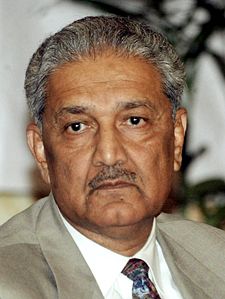

Abdul Qadeer Khan

| Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan HI, NI & BAR (twice) |

|

|

|

| Born | 1 April 1936 Bhopal, British India |

|---|---|

| Residence | Pakistan |

| Nationality | Pakistani |

| Fields | Metallurgy |

| Institutions | Khan Research Laboratories |

| Alma mater | Catholic University of Leuven Delft University of Technology |

| Known for | Pakistani Nuclear Program |

| Notable awards | Hilal-i-Imtiaz (14-8-1989) Nishan-i-Imtiaz (14-8-1996 and 23-3-1999) |

| Religious stance | Islam |

Abdul Qadeer Khan (Urdu: عبدالقدیر خان; born April 1, 1936 in Bhopal, British India) is a Pakistani scientist and metallurgical engineer, widely regarded as the founder of Pakistan's nuclear program. His middle name is occasionally rendered as Quadeer, Qadir or Qadeer, and his given names are usually abbreviated to A.Q..

In January 2004, Khan confessed to having been involved in a clandestine international network of nuclear weapons technology proliferation from Pakistan to Libya, Iran and North Korea. On February 5, 2004, the President of Pakistan, General Pervez Musharraf, announced that he had pardoned Khan, who is widely seen as a national hero.[1] Recently Dr. Qadeer cleared the issue of confession which he said was handed to him by authorities[2].

In an August 23, 2005 interview with Kyodo News General Pervez Musharraf confirmed that Khan had supplied gas centrifuges and gas centrifuge parts to North Korea and, possibly, an amount of uranium hexafluoride.[3]

On May 30, 2008, ABC News reported that Khan, who previously confessed to his involvement with Iran and North Korea, now denies involvement with the spread of nuclear arms to those countries. He explained in an interview with ABC News that the Pakistani government and President Pervez Musharraf forced him to be a "scapegoat" for the "national interest." He denies ever traveling to Iran or Libya and claims that North Korea's nuclear program was well advanced before his visit.[4]

Early life

Khan was born (Bhopal) into a middle-class Muslim-Muhajir family, which migrated from India to Pakistan in 1952. He obtained a B.Sc. degree in 1960 from the University of Karachi, majoring in physical metallurgy. He then obtained an engineer's degree in 1967 from Delft University of Technology, the Netherlands, and a Ph.D. degree in metallurgical engineering from the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium in 1972.[5].

Work in the Netherlands

In 1972, the year he received his PhD, Khan joined the staff of the Physical Dynamics Research Laboratory (FDO) in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. FDO was a subcontractor for URENCO, the uranium enrichment facility at Almelo in the Netherlands, which had been established in 1970 by the United Kingdom, West Germany, and the Netherlands to assure a supply of enriched uranium for the European nuclear reactors. The URENCO facility used Zippe-type centrifuge technology to separate the fissionable isotope uranium-235 out of uranium hexafluoride gas by spinning a mixture of the two isotopes at up to 100,000 revolutions a minute. The technical details of these centrifuge systems are regulated as secret information by export controls because they could be used for the purposes of nuclear proliferation.

In May 1974, India carried out its first nuclear test, code named Smiling Buddha, to the great alarm of the Government of Pakistan. Around this time, Khan having a distinguished career and being one of the senior most scientists at the nuclear plant he worked at, had privileged access to the most restricted areas of the URENCO facility as well as to documentation on the gas centrifuge technology. India's surprise nuclear test and the subsequent Pakistani scramble to establish a deterrent caused great alarm to the Pakistani government as well as the Pakistani diaspora including individuals like Khan. A subsequent investigation by the Dutch authorities found that he had passed highly-classified material to a network of Pakistani intelligence agents; however, they found no evidence that he was sent to the Netherlands as a spy nor were they able to determine whether he approached the Government of Pakistan about espionage first or whether they had approached him. In December 1975, Khan suddenly left the Netherlands; he returned to Pakistan in 1976.[6].

The former Dutch Prime Minister, Ruud Lubbers, said in early August 2005 that the Government of the Netherlands knew of Khan "stealing" the secrets of nuclear technology but let him go on at two occasions after the CIA expressed their wish to continue monitoring his movements.[7][8]

Development of nuclear weapons

In 1976, Khan was put in charge of Pakistan's uranium enrichment program with the support of the then Prime Minister of Pakistan, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. The uranium enrichment program was originally launched in 1974 by Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) as Project-706 and Khan joined it in the spring of 1976. In July of that year, he took over the project from PAEC and established the Engineering Research Laboratories (ERL) at Kahuta, Rawalpindi, subsequently, renamed the Khan Research Laboratories (KRL) by the then President of Pakistan, General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq. The laboratories became the focal point for developing a uranium enrichment capability for Pakistan's nuclear weapons development programme. KRL also took on many other weapons development projects, including the development of the nuclear weapons-capable Ghauri ballistic missile. KRL occupied a unique role in Pakistan's Defence Industry, reporting directly to the office of the Prime Minister of Pakistan, and having extremely close relations with the Pakistani military. The former Prime Minister of Pakistan, Benazir Bhutto, has said that, during her term of office, even she was not allowed to visit the facility (KRL).

Pakistan's establishment of its own uranium enrichment capability was so rapid that international suspicion was raised as to whether there was outside assistance to this program. It was reported that Chinese technicians had been at the facility in the early 1980s, but suspicions soon fell on Khan's activities at URENCO. In 1983, Khan was sentenced in absentia to four years in prison by an Amsterdam court for attempted espionage; the sentence was later overturned at an appeal on a legal technicality. Khan rejected any suggestion that Pakistan had illicitly acquired nuclear expertise: "All the research work [at Kahuta] was the result of our innovation and struggle," he told a group of Pakistani librarians in 1990. "We did not receive any technical know-how from abroad, but we cannot reject the use of books, magazines, and research papers in this connection."

In 1987, a British newspaper reported that Khan had confirmed Pakistan's acquisition of a nuclear weapons development capability, by his saying that the U.S. intelligence report "about our possessing the bomb (nuclear weapon) is correct and so is speculation of some foreign newspapers". Khan's statement was disavowed by the Government of Pakistan. and initially he denied giving it, but he later retracted his denial. In October 1991, the Pakistani newspaper Dawn reported that Khan had repeated his claim at a dinner meeting of businessmen and industrialists in Karachi, which "sent a wave of jubilation" through the audience.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the Western governments became increasingly convinced that covert nuclear and ballistic missile collaboration was taking place between China, Pakistan, and North Korea. According to the Washington Post, "U.S. intelligence operatives secretly rifled Dr. A.Q. [Khan's] luggage ... during an overseas trip in the early 1980s to find the first concrete evidence of Chinese collaboration with Pakistan's [nuclear] bomb effort: a drawing of a crude, but highly reliable, Hiroshima-sized [nuclear] weapon that must have come directly from Beijing, according to the U.S. officials." In October 1990, the activities of KRL led to the United States terminating economic and military aid to Pakistan, following this, the Government of Pakistan agreed to a freeze in its nuclear weapons development program. But Khan, in a July 1996 interview with the Pakistani weekly Friday Times, said that "at no stage was the program [of producing nuclear weapons-grade enriched uranium] ever stopped".[9]

The American clampdown may have prompted an increasing reliance on Chinese and North Korean nuclear and missile expertise. In 1995, the U.S. Government learned that KRL had bought 5,000 specialized magnets from a Chinese Government-owned company, for use in the uranium enrichment equipment. More worryingly, it was reported that the Pakistani nuclear weapons technology was being exported to other states aspirant of nuclear weapons, notably, North Korea. In May 1998, Newsweek magazine published an article alleging that Khan had offered to sell nuclear know-how to Iraq, an allegation that he denied. United Nations arms inspectors apparently discovered documents discussing Khan's purported offer in Iraq; Iraqi officials said the documents were authentic but that they had not agreed to work with Khan, fearing it was a sting operation. A few weeks later, both India and Pakistan conducted nuclear tests (Pokhran-II and Chagai-I, respectively) that confirmed both countries' development of nuclear weapons. The tests were greeted with jubilation in both countries; in Pakistan, Khan was feted as a national hero. The President of Pakistan, Muhammad Rafiq Tarar, awarded a gold medal to him for his role in masterminding the Pakistani nuclear weapons development programme. The United States immediately imposed sanctions on both India and Pakistan and publicly blamed China for assisting Pakistan.

Investigations into Pakistan's nuclear proliferation

Khan's open promotion of Pakistan's nuclear weapons and ballistic missile capabilities became something of an embarrassment to Pakistan's government. The United States government became increasingly convinced that Pakistan was trading nuclear weapons technology to North Korea in exchange for ballistic missile technology. In the face of strong U.S. criticism, the Pakistani government announced in March 2001 that Khan was to be dismissed from his post as Chairman of KRL, a move that drew strong criticism from the religious and nationalist opposition to the President of Pakistan, General Pervez Musharraf. Perhaps in response to this, the Pakistani government appointed Khan to the post of Special Science and Technology Adviser to the President, with a ministerial rank. While this could be regarded as a promotion for Khan, it removed him from hands-on management of KRL and gave the government an opportunity to keep a closer eye on his activities. In 2002, the Wall Street Journal quoted unnamed "senior Pakistani Government officials" as conceding that Khan's dismissal from KRL had been prompted by the U.S. government's suspicions of his involvement in nuclear weapons technology transfers with North Korea.

Khan came under renewed scrutiny following the September 11, 2001 attacks in the U.S. and the subsequent US invasion of Afghanistan to oust the fundamentalist Taliban regime in Afghanistan. It emerged that al-Qaeda had made repeated efforts to obtain nuclear weapons materials to build either a radiological bomb or a crude nuclear bomb. In late October 2001, the Pakistani government arrested three Pakistani nuclear scientists, all with close ties to Khan, for their suspected connections with the Taliban.

The Bush administration continued to investigate Pakistani nuclear weapons proliferation, ratcheting up the pressure on the Pakistani government in 2001 and 2002 and focusing on Khan's personal role. It was alleged in December 2002 that U.S. intelligence officials had found evidence that an unidentified agent, supposedly acting on Khan's behalf, had offered nuclear weapons expertise to Iraq in the mid-1990s, though Khan strongly denied this allegation and the Pakistani government declared the evidence to be "fraudulent". The United States responded by imposing sanctions on KRL, citing concerns about ballistic missile technology transfers.

2003 revelations from Iran and Libya

In August 2003, reports emerged of dealings with Iran; it was claimed that Khan had offered to sell nuclear weapons technology to that country as early as 1989. The Iranian government came under intense pressure from the United States and the European Union to make a full disclosure of its nuclear programme and, finally, agreed in October 2003 to accept tougher investigations from the International Atomic Energy Agency. The IAEA reported that Iran had established a large uranium enrichment facility using gas centrifuges based on the "stolen" URENCO designs, which had been obtained "from a foreign intermediary in 1987." The intermediary was not named but many diplomats and analysts pointed to Pakistan and, specifically, to Khan, who was said to have visited Iran in 1986. The Iranians turned over the names of their suppliers and the international inspectors quickly identified the Iranian gas centrifuges as Pak-1's, the model developed by Khan in the early 1980s. In December 2003, two senior staff members at KRL were arrested on suspicion of having sold nuclear weapons technology to the Iranians.

Also in December 2003, Libya made a surprise announcement that it had weapons of mass destruction programmes which it would now abandon. Libyan government officials were quoted as saying that Libya had bought nuclear components from various black market dealers, including Pakistani nuclear scientists. U.S. officials who visited the Libyan uranium enrichment plants shortly afterwards reported that the gas centrifuges used there were very similar to the Iranian ones.

Dismissal, confession, and pardon

Investigation and confession

The Pakistani government's blanket denials became untenable as evidence mounted of illicit nuclear weapons technology transfers. It opened an investigation into Khan's activities, arguing that even if there had been wrongdoing, it had occurred without the Government of Pakistan's knowledge or approval. But critics noted that virtually all of Khan's overseas travels, to Iran, Libya, North Korea, Niger, Mali, and the Middle East, were on official Pakistan government aircraft which he commandeered at will, given the status he enjoyed in Pakistan. Often, he was accompanied by senior members of the Pakistan nuclear establishment.

Although he was not arrested, Khan was summoned for "debriefing". On January 25, 2004, Pakistani investigators reported that Khan and Mohammed Farooq, a high-ranking manager at KRL, had provided unauthorised technical assistance to Iran's nuclear weapons program in the late 1980s and early 1990s, allegedly in exchange for tens of millions of dollars. General Mirza Aslam Beg, a former Chief of Army Staff at the time, was also said to have been implicated; the Wall Street Journal quoted U.S. government officials as saying that Khan had told the investigators that the nuclear weapons technology transfers to Iran had been authorised by General Mirza Aslam Beg.[10]. On January 31, Khan was dismissed from his post as the Science Adviser to the President of Pakistan, ostensibly to "allow a fair investigation" of the nuclear weapons technology proliferation allegations.

In early February 2004, the Government of Pakistan reported that Khan had signed a confession indicating that he had provided Iran, Libya, and North Korea with designs and technology to aid in nuclear weapons programs, and said that the government had not been complicit in the proliferation activities. The Pakistani official who made the announcement said that Khan had admitted to transferring technology and information to Iran between 1989 and 1991, to North Korea and Libya between 1991 and 1997 (U.S. officials at the time maintained that transfers had continued with Libya until 2003), and additional technology to North Korea up until 2000.[11] On February 4, 2004, Khan appeared on national television and confessed to running a proliferation ring; he was pardoned the next day by Musharraf, the Pakistani president, but held under house arrest.[12]

Information coming from the investigation

The full scope of the Khan network is not fully known. Centrifuge components were apparently manufactured in Malaysia with the aid of South Asian and German middlemen, and used a Dubai computer company as a false front. According to Western sources, Khan had three motivations for his proliferation: 1. a defiance of Western nations and an eagerness to pierce the "clouds of so-called secrecy," 2. an eagerness to give nuclear technology to Muslim nations, and 3. money, acquiring wealth and real estate in his dealings. Much of the technology he sold was second-hand from Pakistan's own nuclear program and involved many of the same logistical connections which he had used to develop the Pakistani bomb.[1] In Malaysia, Khan was helped by Sri Lanka-born Buhary Sayed Abu Tahir, who shuttled between Kuala Lumpur and Dubai to arrange for the manufacture of centrifuge components.[12] The Khan investigation also revealed how many European companies were defying export restrictions and aiding the Khan network as well as the production of the Pakistani bomb. Dutch companies exported thousands of centrifuges to Pakistan as early as 1976, and a German company exported facilities for the production of tritium to the country.[13]

The investigation exposed Israeli businessman Asher Karni as having sold nuclear devices to Khan's associates. Karni is currently awaiting trial in a U.S. prison. Tahir was arrested in Malaysia in May 2004 under a Malaysian law allowing for the detention of individuals posing a security threat.[12]

Pardon and U.S. reaction

On February 5, 2004, the day after Khan's televised confession, he was pardoned by Pakistani President Musharraf. However, Khan remained under house arrest.

The United States government imposed no sanctions on the Pakistani government following the confession and pardon. U.S. government officials said that in the War on Terrorism, it was not their goal to denounce or imprison people but "to get results." Sanctions on Pakistan or demands for an independent investigation of the Pakistani military might have led to restrictions on or the loss of use of Pakistan military bases needed by US and NATO troops in Afghanistan. "It's just another case where you catch more flies with honey than with vinegar," a U.S. government official explained. The U.S. has also refrained from applying further direct pressure on Pakistan to disclose more about Khan's activities due to a strategic calculation that such pressure might topple President Musharraf.

In a speech to the National Defense University on February 11, 2004, U.S. President George W. Bush proposed to reform the International Atomic Energy Agency: "No state, under investigation for proliferation violations, should be allowed to serve on the IAEA Board of Governors—or on the new special committee. And any state currently on the Board that comes under investigation should be suspended from the Board. The integrity and mission of the IAEA depends on this simple principle: Those actively breaking the rules should not be entrusted with enforcing the rules."[14] The Bush proposal was seen as targeted against Pakistan which, currently, serves a regular term on the IAEA's Board of Governors. It has not received attention from other governments.

In western media, Khan became a major symbol of the threat of proliferation. In February 2005, he was featured on the cover of U.S.-based Time magazine as the "Merchant of Menace", labeled "the world's most dangerous nuclear trafficker," and in November 2005, the Atlantic Monthly ran a cover on Khan ("The Wrath of Khan") that featured a picture of a mushroom cloud behind Khan's head.

Subsequent developments

Questioning

In September 2005, Musharraf revealed that after two years of questioning Khan — which the Pakistani government insisted to do itself without outside intervention — that they had confirmed that Khan had supplied centrifuge parts to North Korea. Still undetermined was whether or not Khan passed a bomb design to North Korea or Iran that had been discovered in Libya.[15]

Renewed calls for IAEA access

Since 2005, and particularly in 2006, there have been renewed calls by IAEA officials, senior U.S. congressmen, EC politicians, and others to make Khan available for interrogation by IAEA investigators, given lingering skepticism about the "fullness" of the disclosures made by Pakistan regarding Khan's activities. In the U.S., these calls have been made by elected U.S. lawmakers rather than by the U.S. Department of State, though some interpret them as signalling growing discontent within the U.S. establishment with the current Pakistani regime headed by Musharraf.

In May 2006, the U.S House of Representatives Subcommittee on International Terrorism and Nonproliferation held a hearing titled, "The A.Q. Khan Network: Case Closed?" Recommendations offered by legislators and experts at this hearing included demanding that Pakistan turn over Khan to the U.S. for questioning as well as that Pakistan make further efforts to curb future nuclear proliferation. In June 2006, the Pakistani Senate, subcommittee hearing, issued a unanimous resolution criticizing the committee, stating that it will not turn over Khan to U.S. authorities and defending its sovereignty and nuclear program.

Lack of further action

Neither Khan nor any of his alleged Pakistani collaborators have yet to face any charges in Pakistan, where he remains an extremely popular figure. Khan is still seen as an outspoken nationalist for his belief that the West is inherently hostile to Islam. In Pakistan's strongly anti-U.S. climate, tough action against him poses political risks for Musharraf, who already faces accusations of being too pro-U.S. from key leaders in Pakistan's Army. An additional complicating factor is that few believe that Khan acted alone and the affair risks gravely damaging the Army, which oversaw and controlled the nuclear weapons development programme and of which Musharraf was commander-in-chief, until his resignation from military service on November 28, 2007.[16] In December 2006, the Swedish Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission (SWMDC) headed by Hans Blix, a former chief of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC); said in a report that Khan could not have acted alone "without the awareness of the Pakistani Government".[17]

It has also been speculated that Khan's two daughters, who live in the UK and are UK subjects (thanks to their part-British, part-South African mother Henny), are in possession of extensive documentation linking the government of Pakistan to Khan's activities; such documentation is presumably intended to ensure that no further action is taken against Khan. [18] Conversely, both high-profile government members, such as Muhammad Ijaz-ul-Haq, as well as political opposition parties have expressed their support for Khan, allegations of nuclear trafficking notwithstanding.

Cancer

On August 22, 2006, the Pakistani government announced that Khan had been diagnosed with prostate cancer and was undergoing treatment. On September 9, 2006, Khan was operated at Aga Khan hospital, in Karachi. According to doctors, the operation was successful, but on October 30 it was reported that his condition had deteriorated and he was suffering from deep vein thrombosis.[19]

Release from house arrest

In July 2007, two senior government officials told the Associated Press that restrictions on Khan had been eased several months earlier, and that Khan could meet friends and relatives either at his home or elsewhere in Pakistan. The officials said that a security detail continued to control his movements.[20]

Hospitalization

On March 5, 2008, Khan was admitted to an Islamabad hospital [21] with low blood pressure and fever [22], reportedly due to an infection. He was released four days later after "he gained significant improvement".

Update on Allegations put on him

On July 4th, 2008 he in an interview blamed President Musharraf and Pakistan Army for the transfer to nuclear technology, he said that Musharraf was aware of all the deals and he was the Big Boss for those deals[23].

Writing Columns

On November 12, 2008, he started writing weekly columns in The News International [24] and Daily Jang [25].

Institutes named after Khan

- Dr. A. Q. Khan Research Laboratories (KRL), Kahuta

- Dr. A. Q. Khan Institute of Technology (KIT), Mianwali

- Dr. A. Q. Khan Ophthalmic Research Center, Al-Shifa Trust Eye Hospital, Rawalpindi

- Dr. A. Q. Khan Institute of Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering, Karachi University, Karachi

- Zuleikha - Quadeer Science Block, Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi

- Dr. A. Q. Khan Girls College for Computer Science, Rawalpindi

- Dr. A. Q. Khan College for Science & Technology, Rawalpindi

- Dr. A. Q. Khan Academy of Science, Gulberg, Faisalabad

- Dr. A. Q. Khan Hall & Gymnasium, Pearl Valley Public School, Rawalakot, Azad Jammu & Kashmir

- Dr. A. Q. Khan Block, Al-Markaz Al-Islami, Islamabad

- Dr. A. Q. Khan Center for Software Engineering, Islamabad

- Dr. A .Q. Khan Institute of Computer Sciences & Information Technology, Kahuta

- Dr. Abdul Qaudeer Khan Institute for Developing Engineering Technologies, Lahore

- Dr. A. Q. Khan Institute of Technology & Management, Islamabad

- Dr. A. Q. Khan Block, D.J. Sindh Government Science College, Karachi

- Dr A.Q Khan Laboratory, Physics Department, Cadet College Kohat

See also

- Pakistan and weapons of mass destruction

- Nuclear proliferation

- Nuclear program of Iran

- Mohammad Qadir Hussain

- Iran-Pakistan relations

- Pakistan-North Korea relations

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 William J. Broad, David E. Sanger, and Raymond Bonner, "A Tale of Nuclear Proliferation: How Pakistani Built His Network", New York Times (12 February 2004): A1.

- ↑ Extracts from an telephone interview conducted by the Guardian's correspondent, Declan Walsh

- ↑ "Dr AQ Khan provided centrifuges to N. Korea", Dawn , 25 August 2005

- ↑ ABC News: ABC Exclusive: Pakistani Bomb Scientist Breaks Silence

- ↑ About Dr. Khan's education, achievements and research test http://www.draqkhan.com.pk/about.htm

- ↑ "AQ Khan relative held over attack", BBC News, 12 August 2005

- ↑ "CIA asked us to let nuclear spy go, Ruud Lubbers claims", Expactica , 9 August 2005

- ↑ William J. Broad, David E. Sanger, and Raymond Bonner, "A Tale of Nuclear Proliferation: How Pakistani Built His Network", New York Times (12 February 2004): A1.[1]

- ↑ Kahuta, Khan Research Laboratories, A.Q. Khan Laboratories, Engineering Research Laboratories (ERL), Federation of American Scientists (FAS), accessed July 3, 2007

- ↑ John Lancaster and Kamran Khan, Musharraf Named in Nuclear Probe: Senior Pakistani Army Officers Were Aware of Technology Transfers, Scientist Says", Washington Post, February 3, 2004

- ↑ David Rohde and David Sanger, "Key Pakistani is Said to Admit Atom Transfers", New York Times, 2 February 2004: A1.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Bill Powell and Tim McGirk, "The Man Who Sold the Bomb; How Pakistan's A.Q. Khan outwitted Western intelligence to build a global nuclear-smuggling ring that made the world a more dangerous place", Time Magazine , 14 February 2005, p. 22.

- ↑ Craig S. Smith, "Roots of Pakistan Atomic Scandal Traced to Europe", New York Times , 19 February 2004, page A3

- ↑ The transcript of the speech is available online at "President Announces New Measures to Counter the Threat of WMD", address by President George W. Bush at the National Defense University, February 11, 2004

- ↑ David E. Sanger, "Pakistan Leader Confirms Nuclear Exports," New York Times, 13 September 2005, p. A10

- ↑ Ron Moreau and Zahid Hussain, "Chain of Command; The Military: Musharraf dodged a bullet, but could be heading for a showdown with his Army", Newsweek , 16 February 2004, p. 20.

- ↑ "A Q Khan did not act alone" says Hans Blix team

- ↑ Shyam Bhatia, "Khan's daughter leaves country with important documents", February 16, 2004

- ↑ "Disgraced Pakistani scientist's health poor", Reuters, October 30, 2006

- ↑ Munir Ahmad, "Pakistan Eases Curbs on A.Q. Khan", Associated Press, July 2, 2007

- ↑ "Pakistan nuclear scientist shifted to hospital on infection", IRNA, March 5, 2008

- ↑ "Pakistan's top nuclear scientist discharged from hospital", IRNA, March 9, 2008

- ↑ Dr A.Q Khan's accusition of Pervez Musharraf being involved in transferring nuclear technology to North Korea[2]

- ↑ Dr A.Q Khan's weekly column in The News International[3]

- ↑ Dr A.Q Khan's weekly column in Daily Jang[4]

External links

- Videos

- AQ Khan, Samar Mubarmand talking on Pakistani Nuclear Program

- Samar Mubarakmand telling truth about AQ Khan

- Articles

- "The Wrath of Khan", The Atlantic Monthly (November 2005).

- "Unraveling the A. Q. Khan and Future Proliferation Networks", The Washington Quarterly (Spring 2005).

- "Tracking the technology", Nuclear Engineering International (2004-08-31).

- "BBC profile", BBC.co.uk (2004-02-20).

- Full Text of Khan's Apology aired February 4, 2004 on PTV.

- "Pakistan's Nuclear Father, Master Spy", MSNBC (2003-10-24).

- Reporter Adrian Levy on How the United States Secretly Helped Pakistan Build Its Nuclear Arsenal

- "Kahuta - Pakistan Special Weapons Facilities", Federation of American Scientists.

- http://www.guardian.co.uk/pakistan/Story/0,,1141630,00.html 'I seek your pardon'

- "U.S. Aides See Troubling Trend In China-Pakistan Nuclear Ties; Program's History Could Be A Factor as Sanctions Are Weighed", Washington Post, April 1, 1996

- "Musharraf's speech in Honour of Dr Abdul Qadeer Khan". Pakistan Government site.

- "Exclusive Interview with Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan (Urdu)". UrduPoint Network.

- "Successful Pakistanis Around The World". Friends Korner.

- In Nuclear Net’s Undoing, a Web of Shadowy Deals, NY Times, August 25, 2008.

- Nuclear Ring Was More Advanced Than Thought, U.N. Says, Washington Post, by Joby Warrick, September 13, 2008.

- Online Books

- "Islamic Atomic Bomb for sale in World Black Market, by RV Bhasin". R.V. Bhasin.

- "Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan and Nuclear Pakistan by Shahid Nazir Choudhry (Urdu)". Urdupoint.

- "The Debriefing of Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan by Zahid Malik (Urdu)". Millat.

- Interviews

|

|||||||||||||||||