Pulse-code modulation

Pulse-code modulation (PCM) is a digital representation of an analog signal where the magnitude of the signal is sampled regularly at uniform intervals, then quantized to a series of symbols in a numeric (usually binary) code. PCM has been used in digital telephone systems and 1980s-era electronic musical keyboards. It is also the standard form for digital audio in computers and the compact disc "red book" format. It is also standard in digital video, for example, using ITU-R BT.601. However, uncompressed PCM is not typically used for video in standard definition consumer applications such as DVD or DVR because the bit rate required is far too high.

Contents |

Modulation

In the diagram, a sine wave (red curve) is sampled and quantized for PCM. The sine wave is sampled at regular intervals, shown as ticks on the x-axis. For each sample, one of the available values (ticks on the y-axis) is chosen by some algorithm (in this case, the floor function is used). This produces a fully discrete representation of the input signal (shaded area) that can be easily encoded as digital data for storage or manipulation. For the sine wave example at right, we can verify that the quantized values at the sampling moments are 7, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 14, 15, 15, 15, 14, etc. Encoding these values as binary numbers would result in the following set of nibbles: 0111, 1001, 1011, 1100, 1101, 1110, 1110, 1111, 1111, 1111, 1110, etc. These digital values could then be further processed or analyzed by a purpose-specific digital signal processor or general purpose CPU. Several Pulse Code Modulation streams could also be multiplexed into a larger aggregate data stream, generally for transmission of multiple streams over a single physical link. This technique is called time-division multiplexing, or TDM, and is widely used, notably in the modern public telephone system.

There are many ways to implement a real device that performs this task. In real systems, such a device is commonly implemented on a single integrated circuit that lacks only the clock necessary for sampling, and is generally referred to as an ADC (Analog-to-Digital converter). These devices will produce on their output a binary representation of the input whenever they are triggered by a clock signal, which would then be read by a processor of some sort.

Demodulation

To produce output from the sampled data, the procedure of modulation is applied in reverse. After each sampling period has passed, the next value is read and the output of the system is shifted instantaneously (in an idealized system) to the new value. As a result of these instantaneous transitions, the discrete signal will have a significant amount of inherent high frequency energy, mostly harmonics of the sampling frequency (see square wave). To smooth out the signal and remove these undesirable harmonics, the signal would be passed through analog filters that suppress artifacts outside the expected frequency range (i.e., greater than  , the maximum resolvable frequency). Some systems use digital filtering to remove the lowest and largest harmonics. In some systems, no explicit filtering is done at all; as it's impossible for any system to reproduce a signal with infinite bandwidth, inherent losses in the system compensate for the artifacts — or the system simply does not require much precision. The sampling theorem suggests that practical PCM devices, provided a sampling frequency that is sufficiently greater than that of the input signal, can operate without introducing significant distortions within their designed frequency bands.

, the maximum resolvable frequency). Some systems use digital filtering to remove the lowest and largest harmonics. In some systems, no explicit filtering is done at all; as it's impossible for any system to reproduce a signal with infinite bandwidth, inherent losses in the system compensate for the artifacts — or the system simply does not require much precision. The sampling theorem suggests that practical PCM devices, provided a sampling frequency that is sufficiently greater than that of the input signal, can operate without introducing significant distortions within their designed frequency bands.

The electronics involved in producing an accurate analog signal from the discrete data are similar to those used for generating the digital signal. These devices are DACs (digital-to-analog converters), and operate similarly to ADCs. They produce on their output a voltage or current (depending on type) that represents the value presented on their inputs. This output would then generally be filtered and amplified for use.

Limitations

There are two sources of impairment implicit in any PCM system:

- Choosing a discrete value near the analog signal for each sample (quantization error)

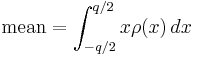

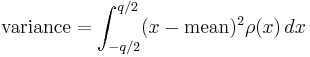

The quantization error swings between  to

to  . In the ideal case (with a fully linear ADC) it is equally distributed over this interval thus with

. In the ideal case (with a fully linear ADC) it is equally distributed over this interval thus with  follows

follows  equals zero while the

equals zero while the  equals to

equals to

- Between samples no measurement of the signal is made; due to the sampling theorem this results in any frequency above or equal to

(fs being the sampling frequency) being distorted or lost completely (aliasing error). This is also called the Nyquist frequency.

(fs being the sampling frequency) being distorted or lost completely (aliasing error). This is also called the Nyquist frequency.

As samples are dependent on time, an accurate clock is required for accurate reproduction. If either the encoding or decoding clock is not stable, its frequency drift will directly affect the output quality of the device. A slight difference between the encoding and decoding clock frequencies is not generally a major concern; a small constant error is not noticeable. Clock error does become a major issue if the clock is not stable, however. A drifting clock, even with a relatively small error, will cause very obvious distortions in audio and video signals, for example.

Digitization as part of the PCM process

In conventional PCM, the analog signal may be processed (e.g. by amplitude compression) before being digitized. Once the signal is digitized, the PCM signal is usually subjected to further processing (e.g. digital data compression).

Some forms of PCM combine signal processing with coding. Older versions of these systems applied the processing in the analog domain as part of the A/D process; newer implementations do so in the digital domain. These simple techniques have been largely rendered obsolete by modern transform-based audio compression techniques.

- Dpcm encodes the PCM values as differences between the current and the predicted value. An algorithm predicts the next sample based on the previous samples, and the encoder stores only the difference between this prediction and the actual value. If the prediction is reasonable, fewer bits can be used to represent the same information. For audio, this type of encoding reduces the number of bits required per sample by about 25% compared to PCM.

- Adaptive DPCM (ADPCM) is a variant of DPCM that varies the size of the quantization step, to allow further reduction of the required bandwidth for a given signal-to-noise ratio.

- Delta modulation, another variant, uses one bit per sample.

In telephony, a standard audio signal for a single phone call is encoded as 8000 analog samples per second, of 8 bits each, giving a 64 kbit/s digital signal known as DS0. The default signal compression encoding on a DS0 is either μ-law (mu-law) PCM (North America and Japan) or a-law PCM (Europe and most of the rest of the world). These are logarithmic compression systems where a 12 or 13 bit linear PCM sample number is mapped into an 8 bit value. This system is described by international standard G.711. An alternative proposal for a floating point representation, with 5 bit mantissa and 3 bit radix, was abandoned.

Where circuit costs are high and loss of voice quality is acceptable, it sometimes makes sense to compress the voice signal even further. An ADPCM algorithm is used to map a series of 8 bit µ-law (or a-law) PCM samples into a series of 4 bit ADPCM samples. In this way, the capacity of the line is doubled. The technique is detailed in the G.726 standard.

Later it was found that even further compression was possible and additional standards were published. Some of these international standards describe systems and ideas which are covered by privately owned patents and thus use of these standards requires payments to the patent holders.

Some ADPCM techniques are used in Voice over IP communications.

Encoding for transmission

Pulse-code modulation can be either return-to-zero (RZ) or non-return-to-zero (NRZ). For a NRZ system to be synchronized using in-band information, there must not be long sequences of identical symbols, such as ones or zeroes. For binary PCM systems, the density of 1-symbols is called ones-density.

Ones-density is often controlled using precoding techniques such as Run Length Limited encoding, where the PCM code is expanded into a slightly longer code with a guaranteed bound on ones-density before modulation into the channel. In other cases, extra framing bits are added into the stream which guarantee at least occasional symbol transitions.

Another technique used to control ones-density is the use of a scrambler polynomial on the raw data which will tend to turn the raw data stream into a stream that looks pseudo-random, but where the raw stream can be recovered exactly by reversing the effect of the polynomial. In this case, long runs of zeroes or ones are still possible on the output, but are considered unlikely enough to be within normal engineering tolerance.

In other cases, the long term DC value of the modulated signal is important, as building up a DC offset will tend to bias detector circuits out of their operating range. In this case special measures are taken to keep a count of the cumulative DC offset, and to modify the codes if necessary to make the DC offset always tend back to zero.

Many of these codes are bipolar codes, where the pulses can be positive, negative or absent. In the typical alternate mark inversion code, non-zero pulses alternate between being positive and negative. These rules may be violated to generate special symbols used for framing or other special purposes.

- See also: T-carrier

History

In the history of electrical communications, the earliest reason for sampling a signal was to interlace samples from different telegraphy sources, and convey them over a single telegraph cable. Telegraph time-division multiplexing (TDM) was conveyed as early as 1853, by the American inventor M.B. Farmer. The electrical engineer W.M. Miner, in 1903, used an electro-mechanical commutator for time-division multiplex of multiple telegraph signals, and also applied this technology to telephony. He obtained intelligible speech from channels sampled at a rate above 3500–4300 Hz: below this was unsatisfactory. This was TDM, but pulse-amplitude modulation (PAM) rather than PCM.

Paul M. Rainey of Western Electric in 1926 patented a facsimile machine using an optical mechanical analog to digital converter. The machine did not go into production. British engineer Alec Reeves, unaware of previous work, conceived the use of PCM for voice communication in 1937 while working for International Telephone and Telegraph in France. He described the theory and advantages, but no practical use resulted. Reeves filed for a French patent in 1938, and his U.S. patent was granted in 1943.

The first transmission of speech by digital techniques was the SIGSALY vocoder encryption equipment used for high-level Allied communications during World War II from 1943. In 1943, the Bell Labs researchers who designed the SIGSALY system, became aware of the use of PCM binary coding as already proposed by Alec Reeves. In 1949 for the Canadian Navy's DATAR system, Ferranti Canada built a working PCM radio system that was able to transmit digitized radar data over long distances[1].

PCM in the 1950s used a cathode-ray coding tube with a grid having encoding perforations. As in an oscilloscope, the beam was swept horizontally at the sample rate while the vertical deflection was controlled by the input analog signal, causing the beam to pass through higher or lower portions of the perforated grid. The grid interrupted the beam, producing current variations in binary code. Rather than natural binary, the grid was perforated to produce Gray code lest a sweep along a transition zone produce glitches.

Nomenclature

The word pulse in the term Pulse-Code Modulation refers to the "pulses" to be found in the transmission line. This perhaps is a natural consequence of this technique having evolved alongside two analog methods, pulse width modulation and pulse position modulation, in which the information to be encoded is in fact represented by discrete signal pulses of varying width or position, respectively. In this respect, PCM bears little resemblance to these other forms of signal encoding, except that all can be used in time division multiplexing, and the binary numbers of the PCM codes are represented as electrical pulses. The device that performs the coding and decoding function in a telephone circuit is called a codec.

See also

- Equivalent pulse code modulation noise

- G.711 – ITU-T standard for audio companding. It is primarily used in telephony.

- Linear Pulse Code Modulation

- Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem

- Pulse-width modulation

- Quantization (signal processing)

- Sampling (signal processing)

- SQNR – One method of measuring quantization error.

Notes

- ↑ Porter, Arthur. So Many Hills to Climb (2004) Beckham Publications Group

References

- Franklin S. Cooper; Ignatius Mattingly (1969). "Computer-controlled PCM system for investigation of dichotic speech perception". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 46: 115. doi:.

- Ken C. Pohlmann (1985). Principles of Digital Audio (2nd ed. ed.). Carmel, Indiana: Sams/Prentice-Hall Computer Publishing. ISBN 0-672-22634-0.

- D. H. Whalen, E. R. Wiley, Philip E. Rubin, and Franklin S. Cooper (1990). "The Haskins Laboratories pulse code modulation (PCM) system". Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers 22: 550–559.

- Bill Waggener (1995). Pulse Code Modulation Techniques (1st ed. ed.). New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold. ISBN 0-442-01436-8.

- Sajad Ahmad (1999). Pulse Code Modulation Systems Design (1st ed. ed.). Boston, MA: Artech House. ISBN 0-89006-776-7.

External links

- Ralph Miller and Bob Badgley invented multi-level PCM independently in their work at Bell Labs on SIGSALY: U.S. Patent 3,912,868: N-ary Pulse Code Modulation.

- According to the National Inventors Hall of Fame, B.M Oliver and Claude Shannon are the inventors of PCM as described in 'Communication System Employing Pulse Code Modulation,' U.S. Patent 2,801,281 filed in 1946 and 1952, granted in 1956.

- Information about PCM: A description of PCM with links to information about subtypes of this format (for example Linear Pulse Code Modulation), and references to their specifications.