Halley's Comet

|

|

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by: | prehistoric; Named after Edmond Halley |

| Discovery date: | 1758 (first predicted perihelion) |

| Alternate designations: | Halley's Comet, 1P (see Designation below) |

| Orbital characteristics A | |

| Epoch: | 2449400.5 (February 17 1994) |

| Aphelion distance: | 35.1 AU (December 9 2023)[1] |

| Perihelion distance: | 0.586 AU |

| Semi-major axis: | 17.8 AU |

| Eccentricity: | 0.967 |

| Orbital period: | 75.3 a[2] |

| Inclination: | 162.3° |

| Last perihelion: | February 9 1986 |

| Next perihelion: | July 28 2061[1] |

Halley's Comet or Comet Halley (officially designated 1P/Halley) is the most famous of the periodic comets and can currently be seen every 75–76 years.[2][3] Although many comets with long orbital periods may appear brighter and more spectacular, Halley is the only short-period comet that is clearly visible to the naked eye, and thus, the only naked-eye comet certain to return within a human lifetime.[4] During its returns to the inner solar system it has been observed by astronomers since at least 240 BC, but it was not recognized as a periodic comet until the eighteenth century when its orbit was computed by Edmond Halley, after whom the comet is now named. Halley's Comet last appeared in the inner Solar System in 1986, and will next appear in mid-2061.[5]

Pronunciation

Halley is generally pronounced /ˈhælɪ/, rhyming with valley,[6] or (especially in the US) /ˈheɪlɪ/ "Hailey",[7] but Edmond Halley himself probably pronounced his name /ˈhɔːlɪ/ "Hawley", with the "hall-" rhyming with "tall" or "small".[8][9]

Computation of orbit

Halley's Comet was the first comet to be recognized as periodic. Perceiving that the observed characteristics of a comet of 1682 were nearly the same as those of two comets which had appeared in 1531 (observed by Petrus Apianus) and 1607 (observed by Johannes Kepler), Halley concluded that all three comets were in fact the same object returning every 76 years (a period that has since been amended to every 75–76 years). After a rough estimate of the perturbations the comet would sustain from the attraction of the planets, he predicted its return for 1758[10]. Halley's prediction of the comet's return proved to be correct, although it was not seen until as late as 25 December 1758 by Johann Georg Palitzsch, a German farmer and amateur astronomer, and did not pass through its perihelion until March 13, 1759, the attraction of Jupiter and Saturn having caused a retardation of 618 days, as was computed by a team of three French mathematicians, Alexis Clairault, Joseph Lalande, and Nicole-Reine Lepaute, previous to its return. Halley himself did not live to see the comet's return, having died in 1742.

The possibility has been raised that 1st century Jewish astronomers had already recognized Halley's Comet as periodic. This theory notes a passage in the Talmud which refers to a "a star which appears once in seventy years that makes the captains of the ships err".[11] [12] No further evidence survives to confirm this possibility.

Orbit and origin

Halley's orbit is highly elliptical, and focused on the Sun. Its perihelion, its closest distance to the Sun, is just 0.6 AU (between the orbits of Mercury and Venus), while its aphelion, or farthest distance from the Sun, is 35 AU, or roughly the distance of Pluto. Unusually for an object in the Solar System, Halley's orbit is retrograde; it orbits the Sun in the opposite direction to the planets, or clockwise from above the Sun's north pole. Its orbit is highly inclined (18°) to the ecliptic, with much of it lying below the orbits of the planets (assuming Earth's north pole to be "up").[13][14] Due to Halley's highly eccentric orbit, it has one of the highest velocities relative to the Earth in the solar system. The 1910 passage was at a relative velocity of 70.56 km/s (157,800 MPH).[15]

Halley is classified as a short period comet (a descriptor for comets with orbits lasting 200 years or less). However, its orbit is such that it is believed to have been originally a long period comet whose orbit was perturbed by the gravity of the giant planets and sent into the inner Solar System. It gives its name to the 'Halley group' of comets, which share these orbital characteristics.[16]

If Halley was once a long period comet, it is likely to have originated in the Oort Cloud, a sphere of cometary bodies which has its inner edge at 50,000 AU. This distinguishes it from most other short period comets, which originate instead from the Kuiper Belt, a flat disc of icy debris between 38 AU (Pluto's orbit) and 50 AU from the Sun.

Chaotic Dynamics

In 1989 Boris Chirikov and Vitaly Vecheslavov [17] performed analysis of 46 comet apparitions known from historical records and computer simulations and showed that the comet dynamics is described by a simple area-preserving map which is rather similar to the standard map. The dynamics of the comet was shown to be chaotic and unpredictable on long time scales due to dynamical chaos. A typical life time of the comet is determined by diffusive escape which is found to be about 10 million years.

Structure and composition

The Giotto mission gave planetary scientists their first view of Halley's surface and structure. Although its coma may extend about 100 million kilometres into space,[18] Halley's nucleus is relatively small (barely 15 kilometres long, 8 kilometres wide and 8 kilometres thick) and roughly peanut-shaped. Its mass is extremely low; roughly 2.2×1014 kg.[19] Its average density is about 0.6 g/cm³, indicating that it is very loosely constructed.[20] Its albedo is about 4 percent, meaning that only 4 percent of the sunlight hitting it is reflected; about what one would expect for coal.[21] Thus, despite appearing brilliant white to observers on Earth, Halley's comet is in fact pitch black. As it approaches the inner Solar System, the Sun warms it, causing its surface to sublimate (change directly from a solid to a gas), and jets of volatile material to burst from its black surface. The nucleus rotates every 52 hours, and its day side is far more active than its night side. The gases ejected from the nucleus are 80 percent water vapour, 17 percent carbon monoxide and 3–4 percent carbon dioxide[22] with traces of hydrocarbons.[23]

The nucleus is covered with a layer of dust, which retains heat. Each large dust grain is thought to consist of many tiny particles with spaces in between. Some of these spaces are filled with ice, and others are empty. When Halley's comet is closest to the Sun, temperatures can rise to about 77 °C. Near the Sun, several tons of gas and dust are emitted each second in the jets. Halley has several shallow craters which are about 1 km in diameter.

Meteor showers

Because its orbit comes close to Earth's orbit in two places, Comet Halley is the parent body of two meteor showers: the Eta Aquarids in early May, and the Orionids in late October.[24] The Eta Aquarids show orbital similarites approaching Earth as they do of Mars and so a meteor shower at Mars is anticipated there as well[25] but this time appearing to come from Lambda Gemini.

Apparitions

Halley's calculations enabled the comet's earlier appearances to be found in the historical record. The comet may have been recorded in China as early as 467 BC, but this is uncertain.[26] The first certain observation dates from 240 BC, and subsequent appearances were recorded by Chinese, Babylonian, Persian, and other Mesopotamian texts. The following list gives the dates of Halley's apparitions since its first recorded appearance in 240 BC.

The astronomical designations for those apparitions are also given.[2][27] The designations consist of Halley's designation ('1P') with the year and half-month of perihelion; for example, "(1P/1982 U1, 1986 III, 1982i" indicates that for the perihelion in 1986, this apparition was the first seen in "half-month" U (the first half of November) in 1982 (giving 1P/1982 U1); it was the third comet past perihelion in 1986 (1986 III); and it was the ninth comet spotted in 1982 (provisional designation 1982i). The perihelion dates of each apparition are shown.[28] The perihelion dates farther from the present are approximate, mainly because of uncertainties in the modeling of non-gravitational effects.

Note that perihelion dates 1607 and later are in the Gregorian calendar, while perihelion dates of 1531 and earlier are in the Julian calendar.[29]

25 May, 240 BC (1P/−239 K1, −239)

The first certain appearance of Halley's comet in the historical record is a description from 240 BC, recorded in the Chinese chronicle Records of the Grand Historian or Shiji, which describes a comet that appeared in the east and moved north.[30]

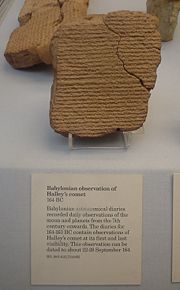

12 November, 164 BC (1P/−163 U1, −163, −162a)

The only surviving record of the 164 BC apparition is found on two fragmentary Babylonian tablets, now owned by the British Museum.[31]

6 August 87 BC (1P/−86 Q1, −86)

The apparition of 87 BC was recorded in Babylonian tablets which state that the comet was seen "day beyond day" for a month.[32]

This appearance may be recalled in the representation of Tigranes the Great, an Armenian king who is depicted on coins with a crown that features, according to V.G. Gurzadyan and R. Vardanyan, "a star with a curved tail [that] may represent the passage of Halley's comet in 87 BC." Gurzadyan and Vardanyan argue that "Tigranes could have seen Halley's comet when it passed closest to the Sun on Aug. 6 in 87 BC" as the comet would have been a "most recordable event"; for ancient Armenians it could have heralded the New Era of the brilliant King of Kings.[33]

10 October 12 BC (1P/−11 Q1, −11)

The apparition of 12 BC was recorded in the Book of Han by Chinese astronomers who tracked it from August through October.[3]

Halley's return in 12 BC, only a few years distant from the supposed date of the birth of Jesus Christ, has led some theologians and astronomers to suggest that it might explain the Biblical story of the Star of Bethlehem. However, there are other explanations for the phenomenon, such as planetary conjunctions, and there are also records of other comets that appeared closer to the date of Jesus's birth.[34]

25 January 66 AD (1P/66 B1, 66)

If, as has been suggested, the reference in the Talmud to "a star which appears once in seventy years that makes the captains of the ships err"[35] (see above) refers to Halley's Comet, it may be a reference to the 66 AD appearance, because this passage is attributed to the Rabbi Yehoshua ben Hananiah. The 66 AD apparition was the only one to occur during ben Hananiah's lifetime.[36]

141 - 760

Computations of Halley's orbit show that it must have appeared nine times between the years 141 and 760.

- 1P/141 F1, 141 (22 March 141). This apparition was recorded in Chinese chronicles.[37]

- 1P/218 H1, 218 (17 May 218)

- 1P/295 J1, 295 (20 April 295)

- 1P/374 E1, 374 (16 February 374)

- 1P/451 L1, 451 (28 June 451)

- 1P/530 Q1, 530 (27 September 530)

- 1P/607 H1, 607 (15 March 607)

- 1P/684 R1, 684 (2 October 684)

- 1P/760 K1, 760 (20 May 760)

28 February 837 (1P/837 F1, 837)

In 837, Halley's Comet may have passed as close as 0.03 AU (3.2 million miles; 5.1 million kilometres) from Earth, by far its closest approach.[38] Its tail may have stretched 60 degrees across the sky. It was recorded by astronomers in China, Japan, Germany and the Islamic world.[3]

18 July 912 (1P/912 J1, 912)

In 912, Halley's Comet is recorded in the Annals of Ulster, which state "A dark and rainy year. A comet appeared."[39]

5 September 989 (1P/989 N1, 989)

The 989 apparition may have been seen by Eilmer of Malmesbury when he was a young boy, as he may have referred to it when writing about the 1066 apparition (see below).

20 March 1066 (1P/1066 G1, 1066)

In 1066, the comet was seen in England and thought to be an omen: later that year Harold II of England died at the Battle of Hastings; it was a bad omen for Harold, but a good omen for the man who defeated him, William the Conqueror. The comet is represented on the Bayeux Tapestry as a fiery star, and the accounts that have been preserved represent it as having appeared to be four times the size of Venus, and to have shone with a light equal to a quarter of that of the Moon.

This appearance of the comet is also noted in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Eilmer of Malmesbury may have seen it in 989, as he wrote of the comet in 1066: "You've come, have you?…You've come, you source of tears to many mothers, you evil. I hate you! It is long since I saw you; but as I see you now you are much more terrible, for I see you brandishing the downfall of my country. I hate you!" [40].

The Irish Annals of the Four Masters recorded the comet as "A star [that] appeared on the seventh of the Calends of May, on Tuesday after Little Easter, than whose light the brilliance or light of the moon was not greater; and it was visible to all in this manner till the end of four nights afterwards."[41]

Chaco Native Americans in New Mexico may have recorded the 1066 apparition in their petroglyphs.[42]

1145-1222

The next two apparitions were as follows:

- 1P/1145 G1, 1145 (18 April 1145)

- 1P/1222 R1, 1222 (28 September 1222)

25 October 1301 (1P/1301 R1, 1301)

The 1301 apparition may have been seen by the artist Giotto di Bondone, who represented the Star of Bethlehem as a fire-coloured comet in the Nativity section of his the Arena Chapel cycle, completed in 1305.

10 November 1378 (1P/1378 S1, 1378)

No record has survived of the 1378 apparition.

9 June 1456 (1P/1456 K1, 1456)

In 1456, the comet passed very close to the Earth; its tail extended over 60° of the heavens and took the form of a sabre. According to one story, first appearing in a posthumous biography in 1475 and later embellished and popularized by Pierre-Simon Laplace, Pope Callixtus III excommunicated the 1456 apparition of the comet, believing it to be an ill omen for the Christian defenders of Belgrade, who were at that time being besieged by the armies of the Ottoman Empire. However, no primary source supports the authenticity of this account.

1531-1759

The comet returned four times between 1531 and 1759, the last of which was predicted by Edmond Halley.

- 1P/1531 P1, 1531 (26 August 1531)

- 1P/1607 S1, 1607 (27 October 1607)

- 1P/1682 Q1, 1682 (15 September 1682)

- 1P/1758 Y1, 1759 I, 1758 (13 March 1759)

16 November 1835 (1P/1835 P1, 1835 III, 1835c)

American satirist and writer Mark Twain was born on November 30, 1835, exactly two weeks after the comet's perihelion. In his biography, he said, "I came in with Halley's comet in 1835. It's coming again next year (1910), and I expect to go out with it. The Almighty has said no doubt, 'Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.' " Twain died on April 21, 1910, the day following the comet's subsequent perihelion.[43][44] The 1985 fantasy film The Adventures of Mark Twain is inspired by this.

20 April 1910 (1P/1909 R1, 1910 II, 1909c)

The April 1910 approach, which came into view around April 20, was notable for several reasons: it was the first approach of which photographs exist, and the comet made a relatively close approach, making it a spectacular sight. Indeed, on May 18, the Earth actually passed through the tail of the comet. The media, despite the pleas of astronomers, wove sensational tales of mass cyanide poisoning engulfing the planet. In reality, the gas is so diffuse that the world suffered no ill effects from the passage through the tail.[45]

Many people who claim to remember seeing the 1910 apparition are probably in fact remembering a different comet, the Great Daylight Comet of 1910, which surpassed Halley in brilliance and was actually visible in broad daylight for a short time about four months before Halley made its appearance.

9 February 1986 (1P/1982 U1, 1986 III, 1982i)

The 1986 approach was the least favourable for Earth observers of all recorded passages of the comet throughout history: the comet did not achieve the spectacular brightness of some previous approaches, and with increased light pollution from urbanization, many people never saw the comet at all. Further, the comet appeared brightest when it was almost invisible from the northern hemisphere in March and April, prompting many amateur astronomers to travel to the southern hemisphere for a glimpse of the interloper. However, the development of space travel allowed scientists the opportunity to study the comet at close quarters, and several probes were launched to do so. The Soviet Vega 1 started returning images of Halley on 1986 March 4, and the first ever of its nucleus, and made its flyby on March 6, followed by Vega 2 making its flyby on March 9. On March 14, the Giotto space probe, launched by the European Space Agency, made a closest pass of the comet's nucleus. There were also two Japanese probes, Suisei and Sakigake. The probes were unofficially known as the Halley Armada.

The first person to visually observe comet Halley on its 1986 return was amateur astronomer Stephen James O'Meara on January 24 1985. O'Meara used a home-built 24" telescope on top of Mauna Kea to detect the magnitude 19.6 comet.[46] As for the naked eye observing, it was Stephen Edberg (then serving as the Coordinator for Amateur Observations at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory) and Charles Morris who were the first to observe Comet Halley with the naked eye in its 1986 apparition.

Based on data retrieved by Astron, the largest ultraviolet space telescope of the time, during its Halley's Comet observations in December 1985, a group of Soviet scientists developed a model of the comet's coma.[47] The comet was also observed from space by the International Cometary Explorer. Originally International Sun-Earth Explorer 3, the probe was renamed and freed from its L1 Lagrangian point location in Earth's orbit to intercept comets 21P/Giacobini-Zinner and Halley.

Two Space Shuttle missions — the ill-fated STS-51-L (the Challenger disaster) and STS-61-E — were scheduled to observe Comet Halley from low Earth orbit. 61-E would have been flown by Challenger in March 1986, carrying the ASTRO-1 platform to study the comet. The mission was canceled, and ASTRO-1 would not fly until late 1990 on STS-35.[48]

Future

The next predicted perihelion of Halley's Comet will be 28 July 2061.

References

Further reading

- Halleio, Edmundo, Astronomiæ Cometicæ Synopsis, Autore Edmundo Halleio apud Oxonienses. Geometriæ Professore Saviliano, & Reg Soc. S., Philosophical Transactions, Vol. 24, No. 297, pp. 1882–1899

- Hughes, D. W., The History of Halley's Comet, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series A, Vol. 323, No. 1572 (Sept. 30, 1987), pp. 349–367.

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Yeomans, Donald K.. "Horizon Online Ephemeris System". California Institute of Technology, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved on 2006-09-08.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 1P/Halley" (1994-01-11 last obs). Retrieved on 2008-10-13.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Kronk, Gary W. "1P/Halley". Retrieved on 2008-10-13. (Cometography Home Page)

- ↑ "Comets, awesome celestial objects". AstronomyToday. Retrieved on 2007-03-15.

- ↑ Osamu Ajiki and Ron Baalke. "Orbit Diagram (Java) of 1P/Halley". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved on 2008-08-01.

- ↑ Random House Dictionary

- ↑ American Heritage Dictionary

- ↑ Flamsteed Astronomy Society (2006). "Huygens, Halley & Harrison — Anniversaries 2006". Retrieved on 2007-03-19.

- ↑ Ian Ridpath. "Saying Hallo to Halley". Retrieved on 2008-07-22.

- ↑ Ian Ridpath. "Halley and his Comet". Retrieved on 2008-08-11.

- ↑ John D. Rayner, A Jewish Understanding of the World (Berghahn Books, 1998), pp.108-11.

- ↑ "The Talmud: Harioth Chapter III". SacredTexts.com. Retrieved on 2007-03-15.

- ↑ Bill Arnett (2001). "Comet Halley". Retrieved on 2007-05-15.

- ↑ Syuichi Nakano (2001). "OAA computing sectioncircular". Retrieved on 2007-05-15.

- ↑ "NEO Close-Approaches Between 1900 and 2200 (sorted by relative velocity)". NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program. Retrieved on 2008-02-05.

- ↑ DAVID C. JEWITT (2002). "FROM KUIPER BELT OBJECT TO COMETARY NUCLEUS: THE MISSING ULTRARED MATTER". Retrieved on 2008-09-14.

- ↑ B.V.Chirikov and V.V.Vecheslavov , Chaotic dynamics of comet Halley, "Astron. Astrophys. 221 (1989) p.146".

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2003. ISBN 0-85229-961-3.

- ↑ G. Cevolani, G. Bortolotti and A. Hajduk (1987). "Halley, comet's mass loss and age". Retrieved on 2007-05-15.

- ↑ RZ Sagdeev; PE Elyasberg; VI Moroz. (1988). "Is the nucleus of Comet Halley a low density body?". AA(AN SSSR, Institut Kosmicheskikh Issledovanii, Moscow, USSR), AB(AN SSSR, Institut Kosmicheskikh Issledovanii, Moscow, USSR), AC(AN SSSR, Institut Kosmicheskikh Issledovanii, Moscow, USSR). Retrieved on 2007-05-15.

- ↑ H. A. Weaver, P. D. Feldman, M. F. A'Hearn, et. al. (28 March 1997). "The Activity and Size of the Nucleus of Comet Hale-Bopp (C/1995 O1)". Science 275 (5308): 1900–1904. doi:.

- ↑ TN Woods; PD Feldman; KF Dymond; DJ Sahnow (1986). "Rocket ultraviolet spectroscopy of comet Halley and abundance of carbon monoxide and carbon". Retrieved on 2007-05-15.

- ↑ Christopher Chyba & Carl Sagan (1987). "Infrared emission by organic grains in the coma of comet Halley". Nature. Retrieved on 2007-05-15.

- ↑ "Meteor Streams". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved on 2007-03-15.

- ↑ "Meteor Showers And Their Parent Bodies". Retrieved on 2007-03-15.

- ↑ M. A. Vilyev, 1917, "Investigations on the Theory of Motion of Halley's Comet"; cited by A. D. Dubyago, 1961, "The Determination of Orbits", chap. 1, The Macmilian Company, New York

- ↑ Vsekhsvyatsky, S. K. (1958), Physical Characteristics of Comets

- ↑ "1P/Halley". Seiichi Yoshida. Retrieved on 2007-03-15.

- ↑ Joseph L. Brady (1982). "Halley's Comet" AD 1986 to 2647 BC". Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, University of California. Retrieved on 2007-03-15.

- ↑ Gary Kronk, Cometography, vol.1 (Cambridge University Press, 1999), p.14.

- ↑ Gary Kronk, Cometography, vol.1 (Cambridge University Press, 1999), p.14.

- ↑ F. R. Stephenson et al, "Records of Halley's comet on Babylonian tablets", Nature 314 (1985), 587 - 592.

- ↑ Gurzadyan, V. G. and Vardanyan, R. (2004). "Halley's comet of 87 BC on the coins of Armenian king Tigranes?". Astronomy & Geophysics (Journal of The Royal Astronomical Society), Vol. 45 (August 4, 2004), p.4.06. Retrieved on 2007-05-10.

- ↑ Colin Humphreys, 'The Star of Bethlehem', in Science and Christian Belief 5 (1995), 83-101.

- ↑ "The Talmud: Harioth Chapter III". SacredTexts.com. Retrieved on 2007-03-15.

- ↑ Yuval Ne'eman (1983). "Astronomy in Israel: From Og's Circle to the Wise Observatory". Tel-Aviv University. Retrieved on 2007-03-15.

- ↑ G. Ravene, 'The appearance of Halley's Comet in A.D. 141', in The Observatory 20 (1897), pp. 203-205.

- ↑ "Great Comets in History". Jet Propulsion Laboratory (1998). Retrieved on 2007-03-15.

- ↑ http://www.ucc.ie/celt/publishd.html

- ↑ William of Malmesbury. Deeds of the English Kings. ISBN 0-19-820678-X.

- ↑ http://www.ucc.ie/celt/publishd.html

- ↑ "Chaco Canyon mystery tour". The LA Times (2005). Retrieved on 2007-03-15.

- ↑ "Directory of Mark Twain's maxims, quotations, and various opinions:". twianquotes.com. Retrieved on 2007-03-15.

- ↑ "The New York Times: 1867-1970". twianquotes.com. Retrieved on 2007-03-15.

- ↑ Ian Ridpath. "Awaiting the Comet". Retrieved on 2008-08-11.

- ↑ Malcolm W. Browne (August 201985). "Telescope Builders See Halley's Comet From Vermont Hilltop". The New York Times. Retrieved on 2008-01-10. (Horizons shows the nucleus @ APmag +20.5; the coma up to APmag +14.3)

- ↑ A model for the coma of Comet Halley, based on the Astron ultraviolet spectrophotometry

- ↑ "Columbia". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved on 2007-03-15.

External links

- Comet Halley nucleus by Giotto spacecraft

- cometography.com

- seds.org

- Orbital simulation from JPL (Java) / Ephemeris

- Donald Yeomans, "Great Comets in History"

- A brief history of Halley's Comet (Ian Ridpath)

| Periodic Comets (by number) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Previous (periodic comet navigator) |

1P/Halley | Next 2P/Encke |

| List of periodic comets | ||